A Cyclic Theory Of Subcultures

David Chapman’s Geeks, MOPs, and Sociopaths In Subculture Evolution is rightfully a classic, but it doesn’t match my own experience. Either through good luck or poor observational skills, I’ve never seen a lot of sociopath takeovers. Instead, I’ve seen a gradual process of declining asabiyyah. Good people start out working together, then work together a little less, then turn on each other, all while staying good people and thinking they alone embody the true spirit of the movement.

I find Peter Turchin’s theories of civilizational cycles oddly helpful here, maybe moreso than for civilizations themselves. Riffing off his phase structure:

Phase 1: Precycle

People start a movement around a weird thing, with no hope of payoff, for sheer love of the thing. They don’t care how many people join, except that maybe they enjoy having more people to talk to about their hobby. There might be fights, but they are nerd fights about technical aspects of the thing. Nobody expects to gain serious status.

Phase 2: Growth

The zeitgeist changes. The thing catches on. Because it’s so new, there is a vast frontier, waiting to be explored. Anyone willing to work hard can go to some virgin tract of ideaspace and start mining it for status. The returns on talent are high. During this phase, the movement grows in three ways.

Forward: People do more of the thing, better. If it’s an artistic movement, they make more art. If it’s an intellectual movement, they discover new things and explore new arguments. If it’s a political movement, they get better-organized and more powerful. Anyone with even a little talent can participate and create something genuinely new. Their work will probably be appreciated within the movement. It might even be appreciated by outsiders, as an example of an exciting new trend.

Upward: People build infrastructure for the movement. They start newsletters. They hold conferences or conventions. They found organizations. Everything is so new, and growing so fast, that even a little talent is enough to succeed. Even if you aren’t an artist yourself, you can still join the art movement, start an art-related newsletter, be the first newsletter to accurately cover the new art form, and make it into the inner circle of the movement, with only a little effort.

Outward: All subcultures are, in a sense, status Ponzi schemes.

Google’s first employee became their Director of Technology and made $900 million. Jesus’s first follower became the Bishop of Rome; one in every thousand people alive is named after him. The first few people to make websites in 1995, blogs in 2005, or YouTube channels in 2015 got outsized followings that they were able to leverage into higher status later on. The first few people to get on board the New Atheist, woke, alt-right, dirtbag left, and intellectual dark web movements all had easy opportunities to become famous; the next few thousand at least had the chance to be well-connected veterans.

Other times the Ponzi is even simpler. In karate, the white belts respect the yellow belts, the yellow belts the green belts, and so on up to the black belts, the instructor, and the World Master Of Your Particular Karate Style Who Lives In A Temple Somewhere In Asia. If you stay around long enough, you gain skills and progress through the ranks. The main selling point is skill at martial arts, but the added bonus is that once you invest enough time, you gain status. You especially gain status compared to people who come after you (eg the people who are white belts when you’re a black belt) but you also gain status in regular society insofar as everyone thinks it’s impressive to be a karate black belt. And how cool other people think it is will depend on the popularity of karate and whether the average person they encounter is more vs. less advanced than you are.

In a normal karate class, status gain is too slow to be worth worrying about. But in a rapidly growing subculture, people catch on fast. This is the secret behind the first two modes of growth. Status within a subculture is zero-sum. You can’t make everyone high-status at the same time. But you can have everyone at time T reasonably expect to be high status at time T+1, after a bunch of new people have joined and the older generation has become Wise Elders and Founding Heroes.

In growth-phase subculture - let’s say one that doubles in size every six months - your status is always improving. And not just because you’re growing older and more experienced, but also because your projects are paying off. Suppose there’s a new art movement of three people. One of them draws the paintings, one writes the manifesto, and one hosts the art shows Ten years later, when the movement has ten thousand people, the first person is a famous pioneering painter, the second person is a public intellectual with a best-selling book, and the third person owns a chain of galleries.

The key to this phase is that no member of the movement has an incentive to compete with any other member. There’s so much open frontier that it would be stupid to waste time backstabbing someone else instead of going off and grabbing the free status lying all around you.

Phase 3: Involution

Thanks to the Chinese for teaching me this lovely word, which I think works better than Turchin’s term “stagflation” in this context.

The movement has picked the low-hanging fruit of their object-level goals. Artistic movements have created enough works that it’s hard not to seem derivative. Intellectual movements have explored most of the implications of their ideas. Political movements have absorbed their natural base and are facing organized opposition. It’s still possible to do object-level work, but unless you’re a hard-working genius, someone will have beaten you to most good ideas.

And the movement already has most of the infrastructure it needs. Want to hold a conference? There are already five top-notch conferences about the movement; unless you’re a hard-working genius, yours will never be as good. Want to start a newsletter? Maybe instead you should beg for an internship at one of the ten newsletters that already compete for readers - too bad a thousand other people are begging equally hard for that same position.

In other situations, everyone would lower their expectations and be fine. But the subculture is used to being a status Ponzi scheme. This is the stage where the last tier joins the pyramid, realizes that there won’t be a tier below them, and feels betrayed.

During this phase, a talented status-hungry young person who joins the movement is likely to expect status but not get it. The frontier is closed; there’s no virgin territory to go homesteading in. The only source of status is to seize someone else’s - ie to start a fight.

Sometimes these fights are object-level: the movement’s art is ugly, its intellectual arguments are false, its politics are unjust. But along with the object level disagreements, there are always accusations that accurately reflect status-famine, ones like “the leaders of this movement are insular and undemocratic” or “the elites don’t listen to criticism”. These accusations may or may not be true. But during the Growth phase, nobody makes them, even when they are true; during the Involution phase, people always make them, even when they aren’t.

Someone with very novel and interesting criticism might start an entirely new subculture based on their ideas; their complaints might suggest a new research direction with unexplored vistas and plenty of free energy. But more likely, they’ll have more minor criticism, and end up vying for the same pool of resources and subcultural energy, only wanting it to be their pool rather than other people’s. This person is now a counterelite (or as they used to call it, a heresiarch).

The average counterelite probably won’t take over the movement. But they can win small victories. They can start a group of True Movementarians, opposed to the corrupt members of the regular movement. Then they can have a True Movementarian conference, a True Movementarian newsletter, etc. This maybe solves the status famine for one more generation.

But the wider effect is fragmentation. During Involution phase, many counterelites are trying to slice off adherents and resources at the same time. Some people even become meta-counter-elites, complaining that the counterelites themselves have strayed from the true principles, etc. The actual elites realize their status is also precarious, and some of them side with the counterelites in order to get a new base, bringing the conflicts to the highest levels. The overall tone of the movement becomes darker. Ordinary rank-and-file members hear so much criticism of the movement that it’s hard for them to stay optimistic about it. They stop talking about it as The Amazing Movement That Will Change Everything, and become defensive: “I’m not, like, one of those members of the movement, I just sort of think some of their ideas make sense sometimes.”

Phase 4: Postcycle

At some point, everyone realizes you can’t get easy status from the subculture anymore. The people who want easy status stop joining, and the movement stabilizes in a low-growth state.

One way for this to happen is institutionalization. A movement rises. It founds some groups to promote its agenda. The fires of excitement die down, and the groups remain. Feminism is no longer as big a deal as it once was, but we still have NOW and Planned Parenthood. These institutions have stopped being social Ponzi schemes. You join them as a day job. You expect to work hard, and at best get a position commensurate to your talent and diligence. It’s not really worth criticizing the leadership, because everything happens through formal governance structures which are hard to affect. Most people who want to be feminists have already decided to support Planned Parenthood and not you. And you cannot take over Planned Parenthood unless you win over their Board of Directors, which you won’t.

(I don’t usually think of karate as an “institution” in the same sense as NOW, but it has strong defenses against criticism and counterelites; you can’t just walk in and argue that you should be the black belt and the master should defer to you)

Other times, the movement just becomes so uncool for so long that it returns to Phase 1. There aren’t a lot of stained glass artisans or Thomist philosophers anymore. But I expect that being a stained glass artisan or Thomist philosopher is an okay job. You might not make much money, but you can have fun exploring your chosen medium in a nerdy way.

No Sociopaths Required

This would be a reasonable point to describe how the subcultures I’ve seen or participated in have followed this scheme, but I’m reluctant to do so - it feels too much like airing dirty laundry.

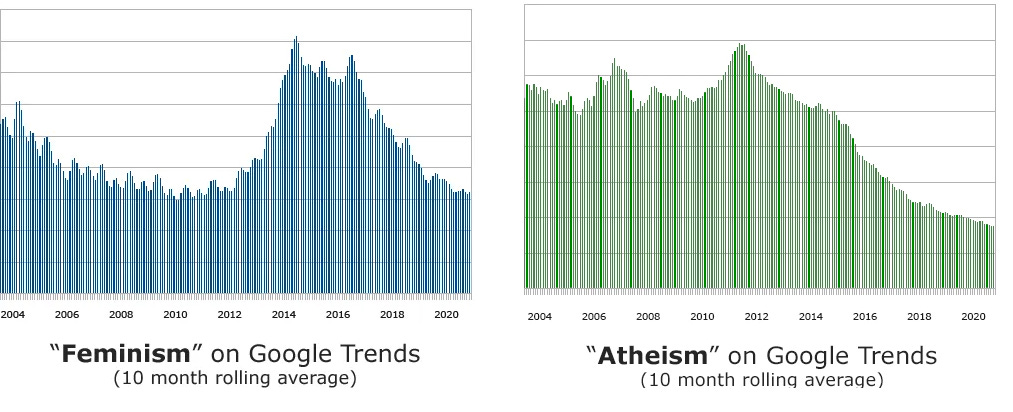

But maybe you will find these graphs helpful. Taken from here.

But maybe you will find these graphs helpful. Taken from here.

But many of them followed a pattern of starting with incredible positive energy. Like telling a new person about them would blow that person’s mind. Everyone felt united in realizing what a good thing they’d got. Then they gradually drifted apart, scandals came out, insiders started absorbing and repeating the outside criticism that had previously seemed so ridiculous, and eventually it reached the point where lots of people were embarrassed to identify with the subculture at all, or did so as explicit meta-contrarianism.

I couldn’t resist including this, but I don’t think EA is actually in full Involution yet.

I couldn’t resist including this, but I don’t think EA is actually in full Involution yet.

Yet unlike Chapman, I never felt like there was any influx of sociopaths. Sometimes I found myself on opposite sides of battle lines from some of the earliest and most valued members of the movement. But I never doubted they were honest; I hope they didn’t doubt me either.

I think during the Involution phase, each faction might well think that the subculture must have been taken over by sociopaths (ie all the other factions). After all, everything used to be so nice and friendly, and now it’s full of people attacking each other for personal gain. But this doesn’t require that the new people be any different in ethics or commitment from the old people. Just more desperate.