All Medications Are Insignificant In The Eyes Of God And Traditional Effect Size Criteria

SSRI antidepressants like Prozac were first developed in the 1980s and 1990s. The first round of studies, sponsored by pharmaceutical companies, showed they worked great! But skeptics found substantial bias in these early trials; several later analyses that corrected for this all found effect sizes (compared to placebo) of only 0.30.

Is an effect size of 0.30 good or bad? The usual answer is “bad”. The UK’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence used to say that treatments were only “clinically relevant” if they had an effect size of 0.50 or more. The US FDA apparently has a rule of thumb that any effect size below 0.50 is “small”.

Others are even stricter. Leucht et al investigate when doctors subjectively feel like their patients have gotten better, and find that even effect size 0.50 correlates to doctors saying they see little or no change. Based on this research, Irving Kirsch, author of some of the earliest credible antidepressant effect size estimates, argues that “[the] thresholds suggested by NICE were not empirically based and are presumably too small”, and says that “minimal improvement” should be defined as an effect size of 0.875 or more. No antidepressant consistently attains this. He wrote:

Given these data, there seems little evidence to support the prescription of antidepressant medication to any but the most severely depressed patients, unless alternative treatments have failed to provide benefit.

…sparking a decade of news articles like Antidepressants Don’t Work - Official Study and Why Antidepressants Are No Better Than Placebos. Since then everyone has gotten into a lot of fights about this, with inconclusive results.

Recently a Danish team affiliated with the pharma company Lundbeck discovered an entirely new way to get into fights about this. I found their paper, Determining maximal achievable effect sizes of antidepressant therapies in placebo-controlled trials , more enlightening than most other writing on this issue. They ask: what if the skeptics’ preferred effect size number is impossible to reach?

Consider the typical antidepressant study. You’re probably measuring how depressed people are using a test called HAM-D - on one version, the scale ranges from 0 to 54, anything above 7 is depressed, anything above 24 is severely depressed. Most of your patients probably start out in the high teens to low twenties. You give half of them antidepressant and half placebo for six weeks. By the end of the six weeks, maybe a third of your subjects have dropped out due to side effects or general distractedness. On average, the people left in the placebo group will have a HAM-D score of around 15, and the people left in the experimental group will have some other score depending on how good your medication is.

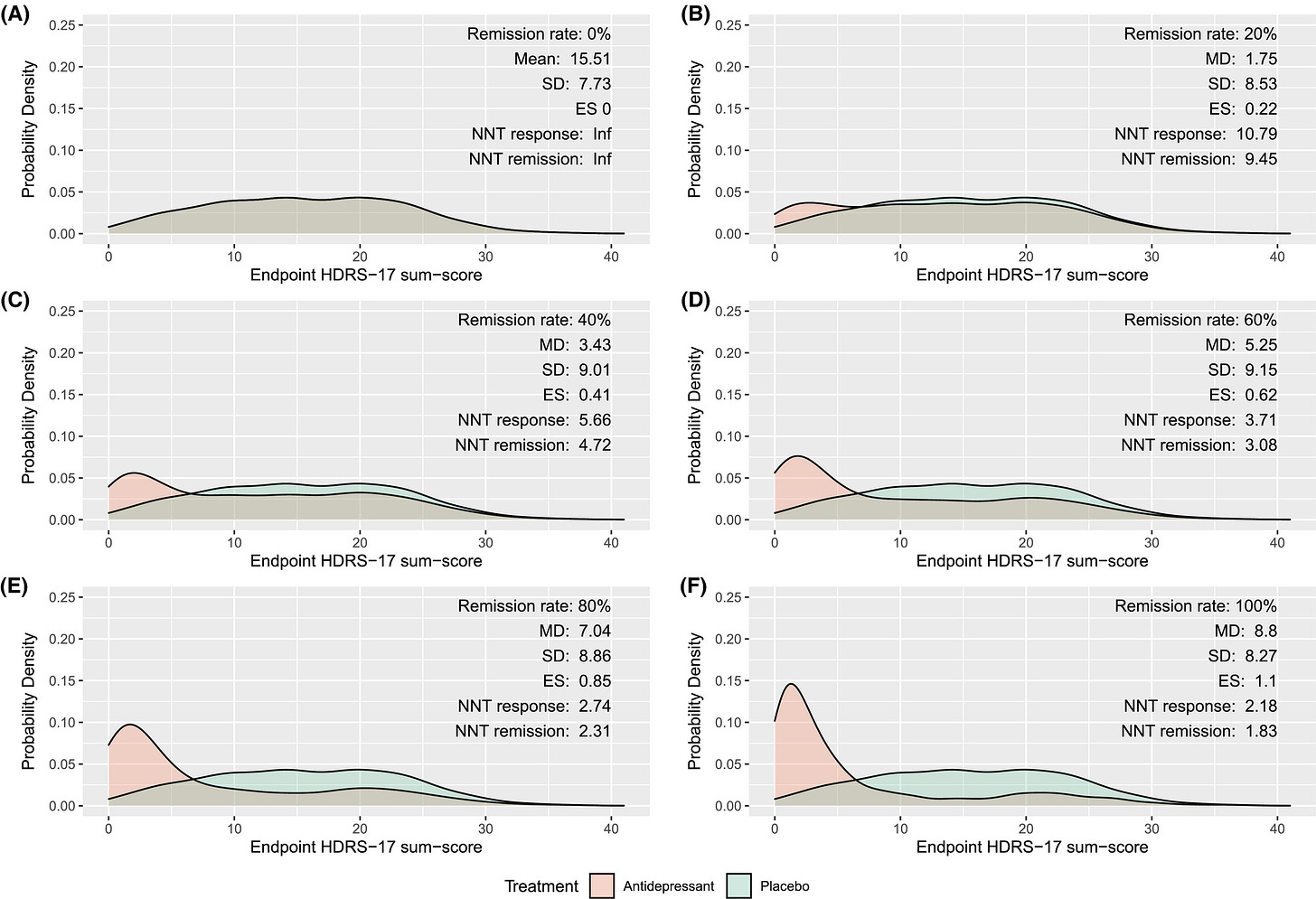

The Danes simulate several different hypothetical medications. The one I find most interesting is a medication that completely cures some fraction of the people who take it. They simulate “completely cures” by giving the patients a distribution of HAM-D scores similar to those of healthy non-depressed people. Here’s what they find:

The pictures from A to F are antidepressants that cure 0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of patients respectively. And we’re looking at the ES - effect size - for each.

Only D, E, and F pass NICE’s 0.50 threshold. And only F passes Kirsch’s higher 0.875 threshold. So a drug that completely cured 40% of people who took it would be “clinically insignificant” for NICE. And even a drug that completely cured 80% of the people who took it would be clinically insignificant for Kirsch! Clearly this use of “clinically insignificant” doesn’t match our intuitive standards of “meh, doesn’t matter”.

We can make this even worse. Suppose that instead of completely curing patients, the drug “only” makes their depression improve a bit - specifically, half again as much as the placebo effect. Here’s the same simulation:

Here we find that only E and F meet NICE’s criteria, and nobody meets Kirsch’s criteria! A drug that significantly improves 60% of patients is clinically insignificant for NICE, and even a drug that significantly improves 100% of patients improve is clinically insignificant for Kirsch!

What’s gone wrong here? The authors point to three problems.

First, most people in depression trials respond very well to the placebo effect. The minimum score on a depression test is zero, and even healthy non-depressed people rarely get zero points exactly. So if most of the placebo group is doing pretty well, there’s not a lot of room for the drug to make people do better than placebo.

Second, this improvement in the placebo group is inconsistent; a lot do recover completely, but others don’t recover at all. That means there’s a large standard deviation in the placebo group. Effect size is measured as a percent of standard deviation. If standard deviation is very high, this artificially lowers effect size.

Third, many patients (often about 30%) leave the study partway through for side effects or other reasons. These people stop taking the medication. But intention-to-treat analysis leaves them in the final statistics. Since a third of the experimental group isn’t even taking the medication, this artificially lowers the medication’s apparent effect size.

I’m not sure about this, but I think NICE and Kirsch were basing their criteria off observations of single patients. That is, in one person, it takes a difference of 0.50 or 0.875 to notice much of a change. But studies face different barriers than single-person observations and aren’t directly comparable.

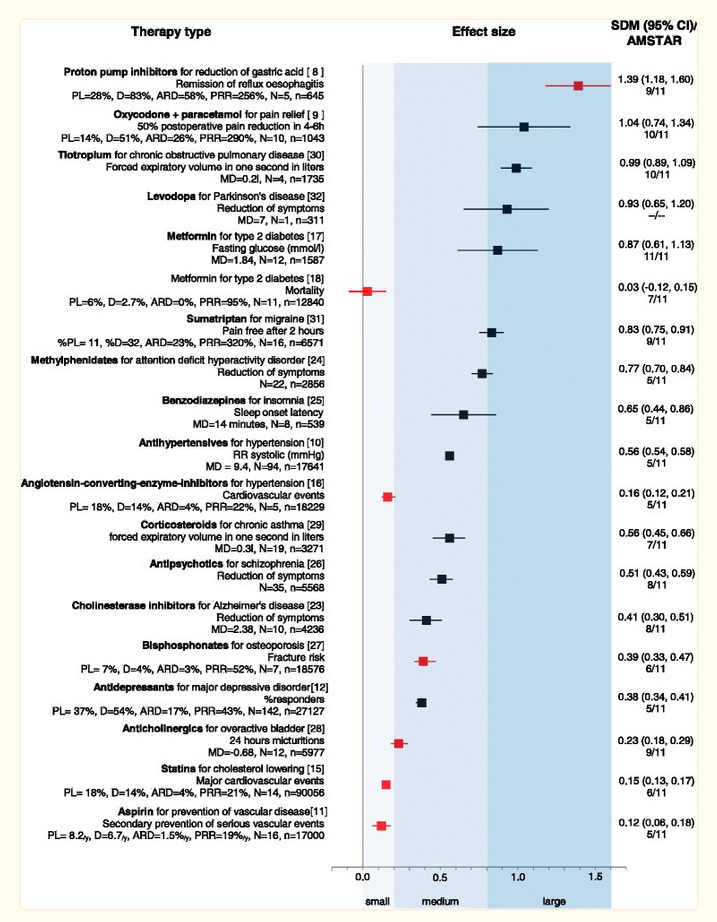

NICE has since walked back on their claim that only effect sizes higher than 0.50 are clinically relevant (although this is part of a broader trend for health institutes not to say things like this, so I don’t want to make too big a deal of it). As far as I know, Kirsch hasn’t. Still, I think that a broader look at medication effect sizes suggests that the Danish team’s effect size laxness is overall right, and the earlier effect size strictness was wrong. Here’s a chart by a team including Leucht, who did some of the original HAM-D research:

Some of our favorite medications, including statins, anticholinergics, and bisphosphonates, don’t reach the 0.50 level. And many more, including triptans, benzodiazepines (!), and Ritalin (!!) don’t reach 0.875.

This doesn’t even include some of my favorites. Zolpidem (“Ambien”) has effect size around 0.39 for getting you to sleep faster. Ibuprofen (“Advil”, “Motrin”) has effect sizes between from about 0.20 (for surgical pain) to 0.42 (for arthritis). All of these are around the 0.30 effect size of antidepressants. There’s no anti-ibuprofen lobby trying to rile people up about NSAIDs, so nobody’s pointed out that this is “clinically insignificant”. But by traditional standards, it is!

Statisticians have tried to put effect sizes in context by saying some effect sizes are “small” or “big” or “relevant” or “miniscule”. I think this is a valiant effort. But it makes things worse as often as it makes them better. Some effect sizes are smaller than we think; others are larger. Consider a claim that the difference between treatment and control groups was “only as big, in terms of effect size, as the average height difference between men and women - just a couple of inches” (I think I saw someone say this once, but I’ve lost the reference thoroughly enough that I’m presenting it as a hypothetical). That drug would be more than four times stronger than Ambien! The difference between study effect sizes, population effect sizes, and individual effect sizes only confuses things further.

I would downweight all claims about “this drug has a meaningless effect size” compared to your other sources of evidence, like your clinical experience.