Ancient Plagues

During our recent discussion of climate change, someone linked me to this New York Magazine piece making the case for doomism.

I disagree with it pretty intensely, but most of my complaints are already listed in the sidebar (some scientists also complained, so they had to add a lot of sidebar caveats in) and I don’t want to belabor them.

The section I find interesting is the one called Climate Plagues:

There are now, trapped in Arctic ice, diseases that have not circulated in the air for millions of years — in some cases, since before humans were around to encounter them. Which means our immune systems would have no idea how to fight back when those prehistoric plagues emerge from the ice.

The Arctic also stores terrifying bugs from more recent times. In Alaska, already, researchers have discovered remnants of the 1918 flu. They actually extracted it from the cadaver of a frozen woman. that infected as many as 500 million and killed as many as 100 million — about 5 percent of the world’s population and almost six times as many as had died in the world war for which the pandemic served as a kind of gruesome capstone. As the BBC reported in May, scientists suspect smallpox and the bubonic plague are trapped in Siberian ice, too — an abridged history of devastating human sickness, left out like egg salad in the Arctic sun.

Experts caution that many of these organisms won’t actually survive the thaw and point to the fastidious lab conditions under which they have already reanimated several of them - the 32,000 year old “extremophile” bacteria revived in 2005, an 8 million-year-old bug brought back to life in 2007, the 3.5 million-year-old one that a Russian scientist self-injected just out of curiosity - to suggest that those are necessary conditions for the return of such ancient plagues. But already last year, a boy was killed and 20 others infected by anthrax released when retreating permafrost exposed the frozen carcass of a reindeer killed by the bacteria at least 75 years earlier; 2,000 present-day reindeer were infected too, carrying and spreading the disease beyond the tundra.

I’m a little nervous talking about this, because I am not a microbiologist. But I haven’t seen the proper experts address this properly, so I’ll try, and if I’m wrong you guys can shout me down.

(Also, the real microbiologists are apparently “self-injecting [3.5 million year old bacteria] just out of curiosity” and we should probably stay away from them for now)

I think we probably don’t have to worry very much about ancient diseases from millions of years ago.

Animal diseases can’t trivially become contagious among humans. Sometimes an animal disease jumps from beast to man, like COVID or HIV, but these are rare and epochal events. Usually they happen when the disease is very common in some population of animals that lives very close to humans for a long time. It’s not “one guy digs up a reindeer and then boom”.

If a plague is so ancient that it’s from before humans evolved, it’s probably not that dangerous. In theory, it could be dangerous for whatever animal it originally evolved for - a rabbit plague infecting rabbits, or an elephant plague infecting elephants. And then maybe after many rabbits are infected, some human might eat an infected rabbit and get unlucky, and the plague might mutate to affect humans. But I don’t think this is any more likely than any of the zillion plagues that already infect rabbits jumping to humans, and nobody is worrying about those.

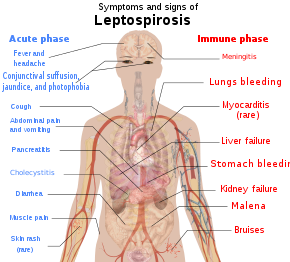

In b4 some medical student jumps in to tell me about leptospirosis.

In b4 some medical student jumps in to tell me about leptospirosis.

The story about anthrax is a distraction. The fact that someone got anthrax from a corpse frozen in permafrost is irrelevant; there is anthrax now, and you could get it from a perfectly fresh corpse or living animal if you wanted. It’s adapted to animals and it can’t spread from person to person. Just because you got an irrelevant-to-humans modern animal disease when you dug up a modern animal, doesn’t mean you’re going to get a dangerous-to-humans disease from an ancient animals.

But I’m more concerned about recent human plagues coming back.

Not bubonic plague; that one is another distraction. The reason we don’t get more Black Deaths isn’t because yersinia pestis died off or mellowed out. It’s because we have good sanitation and pest control.

And doctors whose knowledge of medicine doesn’t begin and end with “look like a creepy bird”

And doctors whose knowledge of medicine doesn’t begin and end with “look like a creepy bird”

But the 1918 Spanish flu has, as far as I know, legitimately died out. Lots of people like saying that in a sense it’s still with us. This NEJM paper (with a celebrity author!) points out that it’s the ancestor of all existing flu strains. But most of these flu strains are less infectious than it was. This didn’t make sense to me the first, second, or third time I asked about it: why would a flu evolve into an inferior flu? Sure, it might evolve into a less deadly flu because it’s perfectly happy being more infectious but less deadly. But I think the Spanish flu was also especially infectious; so why would it evolve away from that?

One possible answer is “because by 1919, everyone had immunity to the 1918 flu, so it evolved away from it - and now nobody has immunity, but it lost the original blueprint.” The 1918 flu was a really optimal point in fluspace, but during all of history up until 1918, the flu’s evolutionary hill-climbing algorithm didn’t manage to find that point, and since flu has no memory it’s not going to be any easier for it to find it the second time, after it evolved away from it. So plausibly, existing flus are strictly worse at their job than Spanish flu was, and digging up an intact copy of the latter would be really bad.

And then there’s smallpox. No mystery why smallpox died out - we killed it. But then we stopped vaccinating people against it, and now if it comes back it would be really bad.

This actually raises a broader question: how worried should we be about getting smallpox from corpses and artifacts in general? Should we freak out every time we dig up an Egyptian mummy? This paper does our freaking out for us - they catalog several incidents of archaeological or incidental excavation of smallpox-infected corpses - including, yes, the mummy of Pharaoh Rameses V.

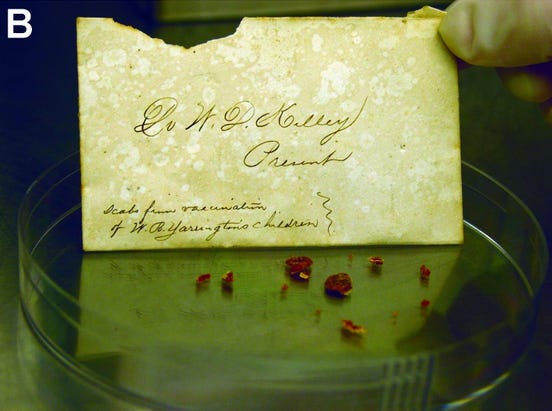

Also: a family in Arkansas was going through an ancestor’s possessions. An envelope fell out of a book containing a note and some weird red stuff; the note said that it was smallpox scabs from a past infection, kept as souvenirs. This sounds like a scene for a horror movie aimed at epidemiologists.

Also: a family in Arkansas was going through an ancestor’s possessions. An envelope fell out of a book containing a note and some weird red stuff; the note said that it was smallpox scabs from a past infection, kept as souvenirs. This sounds like a scene for a horror movie aimed at epidemiologists.

But nobody has ever found evidence of live viable smallpox virus on an artifact or corpse. The article concludes:

Archival specimens offer opportunities to delve into the past and capture a glimpse of the history of an eradicated disease. There are no published reports of residual live microbes found in archeologic relics. Furthermore, on the basis of experiences in the past several decades, risks for transmission of live organisms from such relics would seem to be nonexistent; nevertheless, archeologic specimens should be handled with caution. Each situation should be approached independently and with vigilance and attention.

So I think there’s strong evidence that smallpox can’t survive on relics in normal conditions. But what about frozen in permafrost?

Experiments from back when smallpox walked the earth suggested it could survive a decade or more if you preserved it carefully. There’s some evidence that flu viruses can survive freezing and thawing. And this story mentions a bunch of scientists who tried to search for Spanish flu and smallpox in permafrosted bodies. They didn’t find any live viruses, but there were able to recover a few shreds of useful DNA.

The good news is that these viruses probably can’t be generically “released”. If some dead body with smallpox starts thawing, it’s not like the smallpox virus has been freed from its prison, genie-style, and can travel upon the air currents until it finds an unsuspecting host. You really have to be out there licking corpses.

I think if something goes wrong, the third most likely vector will be curious Siberians who see a corpse half-hidden in the ice and go investigate. The second most likely vector will be archaeologists. And the most likely vector - by far - will be scientists investigating to see whether something could go wrong.

Here is a great article about a guy who digs up ancient Indian burial grounds, searching for samples of especially severe flus. If only we had some sort of cultural folk memory that warned people against doing that kind of thing!

Here is a great article about a guy who digs up ancient Indian burial grounds, searching for samples of especially severe flus. If only we had some sort of cultural folk memory that warned people against doing that kind of thing!