Book Review: Crazy Like Us

We talk a lot about falling biodiversity. Sometimes we apply the same metaphor to the human world, eg “falling linguistic biodiversity” when minority languages get replaced by English or whatever. In Crazy Like Us , Ethan Watters sounds the alarm about falling psychiatric biodiversity. Along with all the usual effects of globalization, everyone is starting to have the same mental illnesses, and to understand them in the same way. This is bad insofar as greater diversity of mental illness could teach us something about the process that generates them, and greater diversity of frameworks and responses could teach us something about how to treat them.

He makes his point through four case studies, starting with:

I. Anorexia In Hong Kong

Until the 1990s, there was almost no anorexia in Hong Kong. There were lots of patriarchal beauty standards, everyone was very obsessed with being thin, but anorexia as a disease was basically unknown.

At least this is the claim of Sing Lee, a Hong Kong psychiatrist who studied in the West. He learned about anorexia during his training in Britain, then went back to Hong Kong prepared to treat it. He couldn’t find anybody. He tried really hard! He put out feelers, asking if anyone knew anybody who was having some kind of psychiatric problem where they were starving themselves. With apologies for the unintended offensive pun - nobody bit.

After a while, he was eventually able to scrounge up a handful of cases. But this was almost more infuriating than nothing at all: the few anorexics he was able to find couldn’t be less interested in thinness or beauty standards or anything like that. Also (unlike in the West) they weren’t delusionally sure that they were fat. They were very aware that they were starving themselves to death, and they were against this. They just felt like they had some sort of nausea or stomach disease which made it impossible for them to eat. The stomach doctors said they were fine, and usually this started during some time of profound stress, so it was reasonable to think this was a mental disorder - and given that, it was probably reasonable to call it anorexia. It just didn’t look like the typical Western version where people were scared of being fat and really wanted to be thin so they could be be ballerinas or whatever. The would-be ballerinas were just dieting normally and becoming ballerinas, and other people with unrelated stresses were getting anorexia.

This lasted until November 24, 1994, when a photogenic schoolgirl collapsed and died on a busy Hong Kong street in the middle of rush hour. The cause of death appeared to be anorexia, a condition most Hong Kongers had never heard of. News cameras caught the whole thing, covered it out of morbid fascination, and it became a sort of national panic. Western experts were flown in to hold public awareness campaigns where they went on TV and said that anorexia was a debilitating condition where patriarchal-beauty-standard-obsessed women dieted to death, and no doubt it was rampant in Hong Kong, and it was important that everyone be aware of how rampant it was so that the problems of ignorance and underdiagnosis could be fixed. Experts would go into girls’ boarding schools and lecture the students about how much anorexia they probably had and how publically aware of it they needed to be.

(the few Hong Kong experts who were consulted mentioned that they basically never saw anorexic patients, that none of their anorexic patients seemed especially fixated on beauty or thinness, and that they suspected the dead girl was just a rare outlier)

Anyway, after a few months of this, psychiatrists reported loads of anorexia cases, hundreds of times as many as there had been before the public awareness campaigns, and all the patients said it was definitely because they were afraid of being fat. The doctors were left extremely suspicious that the public awareness campaign had been a vector for the condition.

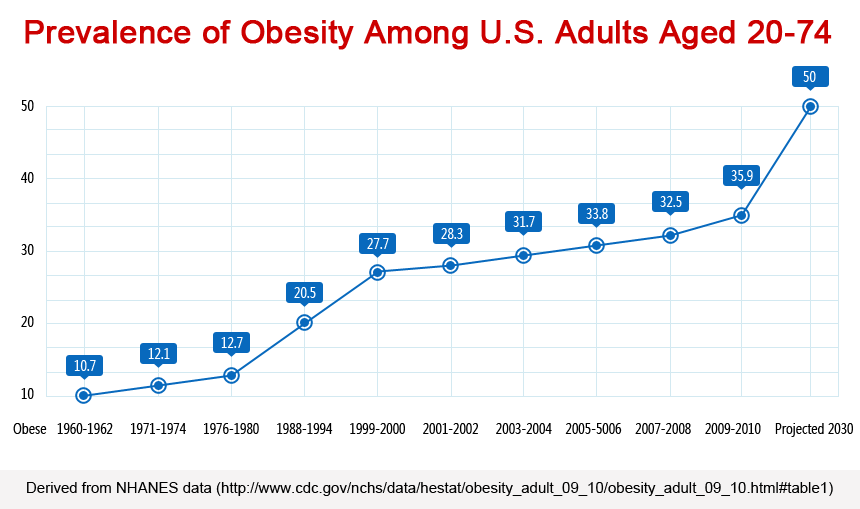

Weirdly enough, all of this had happened before. According Watters, pre-industrial Europe had the same pattern of anorexia as Hong Kong - rare, extremely scattered cases, mostly for stress reasons unrelated to beauty standards (plus or minus a couple of weird nuns). At the dawn of scientific psychiatry in the 19th century, most neurotic illnesses among women were classified under the general heading of “hysteria”. Common hysterical symptoms were nervous tics, sudden inexplicable paralysis of the limbs, on-and-off blindness, convulsions, amnesia, and inability to walk (none of which are typical symptoms of depression/anxiety today!) Around the 1850s, some hysterics started also having something like anorexia. Psychiatrists found this fascinating, wrote a bunch of well-received papers about it, and it became a common topic of discussion in Victorian salons. As interest in the disease spread, so did the disease itself, with anorexia going from one of the rarest hysterical symptoms to one of the most common. Incidence peaked around 1900, after which it slowly trailed off, until around 1940 it was vanishingly rare again. Watters quotes medical historians who attribute this to decreasing interest: once it became so dirt-common that doctors stopped writing papers about it and high-society types stopped talking about it in hushed voices, it became boring and gradually died out. The disorder came back in the 1970s and 80s, for a bunch of reasons. First, a famous singer, Karen Carpenter, collapsed on stage from anorexia, making the news in the same way as the Hong Kong schoolgirl case. Second, terrible 1970s feminists learned about it and started romanticizing it as some sort of brave hunger strike against the patriarchy. Third, and probably most important, US obesity rates went like this:

(source)

(source)

By the late 1980s, anorexia had “caught on” a second time, and people were getting it at higher rates than ever.

Here Watters is working off a theory, sometimes raised by psychiatrists and medical historians, that I think of as a kind of Kantian perspective on mental illness. Kant, remember, said that we have no idea what actual reality is; we see reality through the filter of our own preconceived notions and mental categories, and although there is an external world, we shouldn’t claim to know very much about it. In the same way, Watters suggests, there probably is some base-level objectively-real mental illness. If you have to think of it as something, you can think of it as formless extreme stress, looking for an outlet. But the particular way the stress finds an outlet is based on the patient’s cultural preconceptions. If you believe that stressed people go blind, you’ll go blind. If you believe that stress people act possessed by demons, you’ll act possessed by demons. And if you believe that stressed people become obsessed with being really thin and starve themselves, you might become obsessed with being really thin and starve yourself. A few people will have some natural tendency towards one outlet or another - there are a tiny handful of anorexics even in societies like pre-1990 Hong Kong that don’t recognize anorexia, just as there are a few modern Westerners who still act possessed by demons. But unless you’re especially predisposed towards some method or another, your stress will take the outlet already worn to a deep groove by your cultural milieu.

Does this explain what happened in Hong Kong? I’m not sure.

First, my own theory of anorexia (discussed here) is that it’s a natural (though hard-to-explain) response to any extreme ego-syntonic dieting - if you extreme-diet long enough, and enjoy it, and maybe have a certain predisposition, your body will “get stuck” in extreme dieting mode and refuse to go back. This would explain why medieval nuns who got too into fasting got it. It would explain why modern Westerners who get too into looking beautiful get it. It would explain why pre-1990 Hong Kongers who were really depressed and couldn’t eat got it. It would even explain why Sing Lee got it. Lee (the psychiatrist whose work on Hong Kong anorexia frames the chapter) had a proper old-school experimental temperament, and decided that he wouldn’t be able to treat anorexics unless he really understood them. So he decided to starve himself, and for the first three months it was just as unpleasant as you would expect, and then after that it started being really fun, and he felt great about it, and he had to call off the experiment because he didn’t want to actually give himself anorexia. I’m not sure how to square this with the culture-bound syndrome position. Maybe whether or not a given extreme diet becomes anorexia is culture-bound? Maybe learning about anorexia inspires a bunch of wannarexics who then start dieting? I don’t know, but it doesn’t really fit.

Second, there’s something weird about which societies have weight problems to begin with. Mid-20th-century America had low rates of overweight and obesity. Around 1970, rates began to grow very quickly; the same happened in other countries with various time delays. I don’t have a graph for Hong Kong, but here’s China:

So sure, 1980s Hong Kong had thinness-based beauty standards without any anorexia. But maybe that’s because everyone met the thinness-based beauty standard easily. Once this became hard, and “what if I’m too fat?” became a serious concern, people started getting anorexia. For all I know this happened in the 1990s, although if it’s true that doctors started seeing orders of magnitude more anorexics over the space of a few months I guess that’s still a bit fast for this explanation. Still, it’s worth keeping in mind.

Third, what about the obvious null hypothesis: there were lots of anorexics, they were being anorexic in secret (as most anorexics do!), and nobody took them to the doctor because nobody realized “my weird daughter is dieting too much” was a medical problem? I am a little skeptical of this because in America most advanced cases of anorexia end up with psychiatrists whether or not the patient tries to cover it up, simply because they pass out from lack of food, end up at the hospital, and then the hospital doctors get a psych consult. Of all psych disorders, anorexia is kind of the hardest to push a “suffering in silence” hypothesis for. Still, this is going to come up again and again, so we should at least consider it.

II. Depression In Japan

The frame story here is about a top anthropologist invited by GlaxoSmithKline to a lavish conference at a five-star resort in Japan. They asked him a bunch of questions about the cultural construction of mental illness. He pressed deeper and learned they were trying to “raise awareness of” depression in Japan as part of their effort to market the antidepressant Paxil there. This had, Watters thinks, much the same effect as “raising awareness of” anorexia in Hong Kong.

Here I’m less sure about where Watters is going. It seems like a stretch to argue that 1990s pharma companies introduced depression to Japan - a country where committing suicide is basically the national pastime. But Crazy Like Us tries its best. It says that although Japanese people commit lots of suicide, in their culture this is considered a reasonable response to feeling like they’ve shamed their family or lost their honor or something, very different from the Western idea of “some person isn’t able to cope with their depression and shoots themselves in a fit of despair they would have regretted in a few days if they had lived”. And although pre-1990s Japanese people sometimes got, let’s say, “spells of low mood”, they thought of this as a normal part of life which it’s important to go through and probably learn lessons from.

A sign at Aokigahara, a popular Japanese suicide hotspot, urges visitors not to kill themselves.

A sign at Aokigahara, a popular Japanese suicide hotspot, urges visitors not to kill themselves.

The pre-1990s Japanese word for depression was utsubyo , which meant a lifetime tendency to extremely severe depression that would probably land you in a mental hospital. Utsubyo was considered a rare but severe mental illness much like schizophrenia, one that a few unlucky people had, probably for genetic reasons, but that most people would never have to worry about.

(I don’t remember if Watters mentions it, but this is also the pre-mid-20th-century American/European conception of depression - there’s nothing particularly Japanese about it. The usual term for this idea is melancholia , sometimes used to mean an especially severe endogenous depression, although other people use the word in different and confusing ways. Better historians than I can debate whether the West saw the concept of melancholia fade gradually into modern depression, or whether it had to do with SSRI-induced marketing campaigns here too; I suspect there was a gradual halfway transition from 1900 - 1990, followed by an extremely sudden transition after the invention of SSRIs and the publication of Listening To Prozac. But let’s go back to pretending this is an exotic Japanese phenomenon.)

As part of GlaxoSmithKline’s marketing work, they replaced utsubyo with a new idea, kokoro no kaze , “cold of the soul”. This was supposed to mean that depression was a minor illness (like a cold), something everyone got occasionally (like a cold), and something that was purely biological and could/should be controlled with medication (like a cold). Japanese people were extremely excited about this and bought Paxil by the bushel, and now they use SSRIs at a rate close to Americans.

I was kind of unimpressed with this chapter. It seems pretty obvious that Japanese people got depressed before Paxil’s marketing campaign, including depressed to the point of suicide. GlaxoSmithKline comes off looking a bit manipulative, but it does kind of seem like the rush to get Paxil after their advertising campaign was less “sinister pharma company invents a new disease” and more “oh my god, there’s a name for this thing that I’m suffering from and maybe someone can help me!” There’s certainly a philosophical issue here - do you shrug off depression as just a part of life, or medicalize it? - but it’s not obvious that there’s anything different or uniquely Japanese about this question, or that Westerners made anything worse by exposing Japan to our solution.

Much more fun was the history of Japanese mental illness, which focused on neurasthensia. This was another one of those fully-generic late-1800s diagnoses like hysteria (I assume late-1800s psychiatrists just sort of flipped a coin: heads you were neurasthenic, tails you were hysteric). Around the Meiji Restoration, when everyone was obsessed with how great foreign stuff was, Japanese medical students went to Germany, learned psychiatry, came back to Japan, and told everyone they were neurasthenic. Being neurasthenic became first a fashion, then a class marker. The idea was that neurasthenics were people who were working too hard (good, admirable), and who were so smart and doing so much furious intellectual activity that it was straining their nerves (impressive). Also, they were probably sensitive souls too pure for this world. The most embarrassing extreme of this happened in 1903, when some photogenic Japanese youth carved a poem in a tree, went to a beautiful waterfall, and leapt to his death. Everyone praised him for how sensitive and artistic and neurasthenic this was, and turned him into a posthumous national hero. Meanwhile, “in 1902 an article reported that fully one-third of patients visiting hospitals for consultations were suffering from the new disease.”

Eventually Japanese psychiatrists got fed up, and started announcing that actually neurasthenia sucked and you should not have it. From a 1906 Japanese neurology journal:

These days, young students talk about such stuff as “the philosophy of life”. They confront important and profound problems of life, are defeated, and develop neurasthenia. Those who jump off a waterfall or throw themselves in front of a train are weak-minded. They do not have a strong mental constitution and develop mental illness, dying in the end. How useless they are! Such weak-minded people would only cause harm even if they remained alive.

Finally everyone struck a compromise and agreed that most of the lower-class patients weren’t real neurasthenics (hard-working, intelligent, sensitive, admirable), but had a similar condition, imitating the symptoms of neurasthenia, based on being too weak and pathetic to cope. This seemed to do the trick, and people stopped coming to the hospital with neurasthenia symptoms. Watters writes:

Looking back on the debate, it seems as if acceptance of neurasthenia had been so successful that psychiatrists felt obligated to restigmatize this mental disorder in hopes of limiting its adoption. By the end of World War II the diagnosis had almost completely gone out of style among both psychiatrists and the population at large.

I find this about 1000% more interesting than some debate over whether GlaxoSmithKline marketed Paxil too aggressively. He who has ears to hear, let him listen.

III. PTSD In Sri Lanka

In 2004, a magnitude 9 earthquake struck the Indian Ocean. The resulting tsunami devastated Southeast Asia. One of the worst-affected countries was Sri Lanka, where 30,000 people died and millions were left homeless.

Foreign aid agencies sprung into action to try to support the survivors. Joining in the general mobilization were Western mental health professionals, who predicted a [insert some term other than “wave”] of post-traumatic stress disorder cases.

I cannot do justice to Crazy Like Us ’ excellent portrayal of these people. They combined a genuine and admirable desire to go halfway around the world to help people in need, with a burning desire to be “culturally sensitive” and reject “white savior narratives”, with a total lack of even the tiniest amount of actual knowledge about Sri Lanka. The island nation was [insert some term other than “inundated” or “flooded”] with a [insert some term other than “tide”] of counselors, therapists, and psychiatrists, holding public awareness campaigns, appearing on TV/radio/etc, browbeating Sri Lankan officials for not caring enough about the mental health aspect of recovery. Through this whole process they were all tripping over each other to look culturally aware despite having no clue what they were doing. My favorite anecdote was the training lectures, where earnest sensitivity counselors would tell play therapists not to play “Go Fish” with young survivors - given that many of their parents had just been swallowed by the sea.

According to [insert some author name other than “Watters”], mostly things went like this: foreign counselors would go into a refugee camp and tell everyone that they had to speak openly about their trauma and emotions. The survivors would say that it sucked a lot that their families had just been killed, but wouldn’t seem very emotional about it, or really confess to having “trauma” as classically understood. The therapists would say this was very bad, and they were keeping all of their emotions “bottled up”, and they really had to “let it out” or else it would fester and they would end up with PTSD. The refugees, who were never exactly clear which sets of white people were giving out free food and which ones weren’t, figured they ought to do what these people wanted in case they were the free food ones. So they would say, fine, they all felt very emotional and had lots of trauma. The therapists would be delighted and move on to the next camp.

Sri Lanka tsunami refugee camp (source)

Sri Lanka tsunami refugee camp (source)

Watters compares this to the traditional Sri Lankan approach to trauma. The locals had had ample opportunity to refine this, since the country was in the middle of a horrendous civil war full of child soldiers, torture, and sexual violence. The traditional approach was:

In the cosmology of [Sri Lankan] villagers, humans are vulnerable to what they call the “gaze of the wild”, the experience of being looked in the eye by a wild spirit, which can take the form of a human being intent on violence. According to this belief it is not witnessing violence that is destructive. Rather, the moments of terror that come from violence leave one vulnerable to being affected by the gaze. Struck by such a gaze, one enters an altered state of consciousness and can become violent oneself, behave lasciviously, become physically imobilized, or in other ways step outside of normal modes of social behavior. Somatic symptoms, including chronic headaches, stomach aches, and loss of bodily strength, are also common […]

These semitrance states are treated in the village with a long and arduous cleansing ritual. Such ceremonies often last up to thirty hours, during which the afflicted person is encouraged to dance, tremble, and speak in tongues at specific times during the ceremony. The rituals themselves are designed to elicit fear. Healers elaborately disguised as wild spirits visit the sick, often in the early hours of the morning, in order to frighten the subject as severely as possible. Often those who complete these cleansings show dramatic recoveries […]

Stories or even words describing the violence were considered literally dangerous. Because of this, the community had established a complex set of rules for how villagers are allowed to talk about or remember the violence. [Anthropologist] Argenti-Pillen had to learn a complex dialect of “cautious words” that allow someone to reference a horrifying event without explicitly bringing it to mind. On examining these local euphenisms, she began to see that they were intentionally replacing words or phrases that might invoke fear or moral anger with those that connote safety and trust. Torture, for example, was evoked with a word that also means a child’s mischief.

(though before you start thinking of this as too exotic, remember that the Irish called their own ethnic violence “The Troubles”)

The story continues: local rebels/troublemakers/punks had set up a counterculture where they scare and alienate everyone else by talking about violence in taboo ways all the time and maybe kind of glorifying it. When Western psychologists came in and said that everyone was wrong to have taboos around trauma and actually they should be talking about it openly, some locals worried that this was tipping the delicate balance of social power in favor of the rebels and condemning the people handling things more traditionally.

Okay, so importing western notions of trauma to Sri Lanka was hard, chaotic, comedic at times, and maybe upset some delicate balance of power. But was it actually bad?

Watters points to research showing that “psychological debriefing” - the practice of sending mental health professionals to talk to recently traumatized people and have a single brief session where they “process” the trauma - is counterproductive and makes trauma worse. This is true in Western countries, and it’s probably true in Sri Lanka as well. So the psychological relief effort itself probably did more harm than good. Darn.

Still, I feel like the broader point of this chapter kind of fails to [insert some word other than “land”]. Watters makes a big deal of subtle differences in the way Westerners and Sri Lankans think about trauma (for example, Sri Lankans are more often to think of it as a hole in the social fabric, eg “I should have a father and I don’t and that’s disrupting the network of relationships in a way that produces symptoms”, rather than the more internalized Western “the experience of losing my father has caused some imprint on my brain which produces symptoms”) But the part about local trauma practices during the civil war make it pretty clear that pre-globalization Sri Lanka had something pretty PTSD-like. Although it violates one of our taboos to try to change a local culture’s traditions, Watters didn’t put much work into trying to show that the Sri Lankan traditions were as good/better as the Western traditions. Sure, don’t have one-visit immediate semi-forced debriefing sessions (in either Sri Lanka or the US). But if someone shares the consensus western position that lots of therapy and processing and emotional awareness is important to healing PTSD, there’s not much here that will convince them otherwise.

As before, the part I found most enlightening was the history of trauma. Although cultures throughout history have included some people with bad reactions to traumatic events, it’s controversial whether this has happened at anywhere near the levels of today. Historians can hunt down some things Romans said that sounded vaguely PTSD-like, but the fact is that a very large segment of their society was going into a bunch of pitched sword battles and/or crucifying people for fun and profit, and mostly pretty blase about it. We don’t have great records for historical traumatized populations, but it would surprise me if eg antebellum slaves had classic PTSD symptoms at the same rate as Afghan War veterans.

In fact, at the very beginning of the emergence of modern PTSD - around the Vietnam War - the original researchers of the condition called it “post-Vietnam syndrome” and tried to define it as a distinctly Vietnamese experience. The idea was that soldiers in past “good” wars had been fighting for something they believed in , had the support of the population back home, and didn’t have psychological problems. Since soldiers in Vietnam were developing all these new symptoms, that was yet more evidence that it was a “bad” war which had to be stopped. Over the course of decades (plus lots of marketing by enthusiastic therapists), PTSD expanded from a Vietnam-only problem, to all wars, to all natural disasters, to abuse and sexual violence, to the modern understanding where people say they got PTSD from a bad boss, a bad roommate, or an insufficiently woke college reading assignment. I enjoyed The Body Keeps The Score partly because it told the other side of this history, from one of the researchers involved in the popularization, who faced roadblocks like “the VA refused to fund studies because they couldn’t see what relevance PTSD might have for veterans”.

(once again, this is starting to feel less like true deep cross-cultural differences, and more like a couple of decade lag between an idea taking over America and it taking over somewhere else)

IV. Schizophrenia In Zanzibar

If you want an objectively real psychiatric illness with no culture-bound component, schizophrenia is as close as you’re going to get. For one thing, it’s mostly genetic (80% in twin studies). For another, it has pretty uniform prevalence: everywhere from Abhkazia to Zanzibar, 1% of the population gets schizophrenia.

(the most significant exception is certain groups of immigrants who move from developing to developed countries - expect a blog post on that eventually)

The interesting cross-cultural aspect of schizophrenia is prognosis. Studies in the 80s and 90s suggested that developing countries had better outcomes than developed ones. This sparked some interest in figuring out what developing countries were “doing right” and whether we could replicate it.

Since the 80s and 90s, there’s been a bit of backlash against this theory from scientists who suggest that developing countries have less strict criteria for schizophrenia, frequently diagnosing people who have only mild transient psychosis. Obviously if you diagnose less sick people, their prognosis will be better, and this might explain the entire effect. E Fuller Torrey, a top schizophrenia expert, rejects both the uniformity of schizophrenia and the superiority of developing world treatment. I’m not sure what the consensus is on these questions, but my read is that most people still think it’s uniform prevalence but are split on the developing world question.

Torrey also holds a permanent place in my heart for his theory correlating a rise in cat fanciers in the 1800s with a simultaneous rise in schizophrenia, though I think recent studies have not been kind to this thesis.

Torrey also holds a permanent place in my heart for his theory correlating a rise in cat fanciers in the 1800s with a simultaneous rise in schizophrenia, though I think recent studies have not been kind to this thesis.

Anyway, Watters either hasn’t heard about any of this or doesn’t think it’s worth mentioning. He cuts straight to the adventures of anthropologists in the East African island of Zanzibar trying to figure out their approach to schizophrenia.

The Zanzibaris associate schizophrenia with spirit possession (this seems to be a theme; I assume there is some sort of inspector who comes around and makes sure you attribute mental illness to demons, and if not, they take away your indigenous society license). But they are weirdly blase about this. Their position is that everyone gets possessed by spirits sometimes. If you lose your temper and lash out, that’s a spirit. If you act out of character sometimes, that’s a spirit too. Schizophrenics are possessed by stronger and more dedicated spirits than the rest of us, but it’s a difference in degree, not in kind. When a schizophrenic has a period of lucidity, they interpret it as the spirit having left for a bit, while understanding that it might come back at any time.

The book focuses on one Zanzibar family with a couple of schizophrenic members (remember, schizophrenia is genetic, so it’s not surprising to see lots of it in the same family). The whole extended clan of a dozen or so lives crowded together in a single household. Everyone is constantly doing odd jobs or chores; the schizophrenic family members’ contributions are more limited and less reliable, but they do contribute. The size of the family seems helpful; family members are expected to be ambiently present all the time, so it’s not a disaster or disruption if some people are never going to leave the house and “become independent”.

Watters focuses on two things he thinks Zanzibaris do right. First, they minimize schizophrenia. Because of the spirit-possession aspect, instead of being marked apart as ill and unusual, they’re treated as on a continuum with everyone else (since we all get possessed by spirits sometimes). Even when they take a more medicalized perspective on schizophrenia, they call it by extremely vague terms that don’t differentiate it from mild illness, eg “an attack of the nerves” (this seems to be a universal developing-world euphemism for schizophrenia, shared by eg Latin Americans). Zanzibari schizophrenics never feel that different from anyone else - everyone gets possessed by spirits sometimes, everyone gets attacks of the nerves sometimes, lots of people never leave their family homes.

Second, Zanzibar is low expressed emotion. Lots of studies have shown that schizophrenics do best in low-expressed-emotion households. Sometimes this is glossed as “people don’t yell at them or criticize them”, but other times it’s taken more broadly, to also include fussing over them and praising them and getting excited about them. At its worst, this line of research sometimes bleeds into the bad old theory that schizophrenia is caused by overly-attached mothers, but some studies suggest it has value - schizophrenics in high-expressed-emotion households seem to have many more relapses, and some studies show that schizophrenics separated from their families do better than those who stay with them (presumably because staff are less emotional).

Anyway, according to scientists, America has the highest expressed emotion, Europe and other developed countries are also really high, and developing countries are mostly really low. 67% of Anglo-American families studied qualified as high-expressed-emotion, compared to 48% of Brits, 42% of Chinese, 41% of Mexican-Americans, and 23% of Indians. I am a little boggled by this - my stereotypes say the opposite. EG New England WASPs who never show any emotion at all, stiff-upper-lip Brits and Germans, compared to exuberant Mexicans and extremely high-pressure Asians. I hear woke people talk about how demanding a calm, quiet, low-expressed-emotion environment is white supremacy because only white people care about that kind of thing. But nope, according to Crazy Like Us scientists have determined that white Americans are the highest-expressed-emotion culture in the world. Huh.

Anyway, according to Watters, Zanzibar’s low expressed emotion and lack of differentiation between schizophrenics and neurotypicals suggest that these are part of the “secret sauce” that the developing world uses to beat First World schizophrenia outcomes. As with his other case studies, western psychiatrists are coming to Zanzibar and telling everyone that schizophrenia is purely biological and getting everyone really worked up about it, and probably this is bad.

One background part of this chapter which I enjoyed was the section on biological views of mental illness. Westerners tend to spread these in order to reduce stigma - “has a brain chemical malfunction” sounds better than “is possessed by demons”, or even than “is just inexplicably lazy and weird”. But studies generally show that the biological view of mental illness makes people less sympathetic to the mentally ill, more concerned about them being violent, more interested in avoiding them, etc.

I am skeptical this actually worsens outcomes for schizophrenia; the developed vs. developing world thing is more likely diagnostic differences. Still, oops.

V. Conclusion: Towards Mental Health Unawareness Campaigns

Overall I was only moderately interested in the book’s thesis that we are globalizing American concepts of mental health. With the exception of the genuinely interesting anorexia chapter, the depression/PTSD/schizophrenia chapter all showed societies with pre-existing recognizable versions of these disorders. America got really interested in and heavily medicalized these disorders in the mid-20th century, and now these other societies are getting really interested in and heavily medicalizing them. People who like calling things “colonialist” should call this colonialist, and people who like debating whether or not things are colonialist should debate it, but I’m not sure how much extra we can learn about mental health here.

I was more interested in a sort of sub-thesis that kept recurring under the surface: does naming and pointing to a mental health problem make it worse? This was clearest in Hong Kong, where a seemingly very low base rate of anorexia exploded as soon as people started launching mental health awareness campaigns saying that it was a common and important disease (as had apparently happened before in Victorian Europe and 70s/80s America). But it also showed up in the section on how increasing awareness of PTSD seems to be associated with more PTSD, and how debriefing trauma victims about how they might get PTSD makes them more likely to get it. And it was clearest in the short aside about the epidemic of neurasthenia in Japan after experts suggested that having neurasthenia might be cool, which remitted once those experts said it was actually cringe. A full treatment of this theory would go through the bizarre history of conversion disorder, multiple personality disorder, and various mass hysterias, tying it into some of the fad diagnoses of our own day. I might write this at some point.

Of course, the null hypothesis is that there are lots of people suffering in silence until people raise awareness of and destigmatize a mental illness, after which they break their silence, admit they have a problem, and seek treatment. I am slightly skeptical of this, because a lot of mental health problems are hard to suffer in silence - if nothing else, anorexia results in hospitalizations once a patient’s body weight becomes incompatible with healthy life. Still, this is an important counterargument, and one that I hope people do more research into.

This book is about cultures that respond to mental disease very differently than we do, so I find myself imagining a culture that holds Mental Health Unawareness Campaigns. Every so often, they go around burning books about mental illness and cancelling anyone who talks about them. If they must refer to psychiatric symptoms in public, they either use a complicated system of taboos (like Sri Lankans) or maximally vague terms like “an attack of nerves” (like Zanzibaris). Whenever there is a major natural disaster, top experts and doctors go on television reassuring everyone that PTSD is fake and they will not get it. Whenever there’s a recession or something, psychiatrists tell the public that they definitely won’t get depressed, since “depression” only applies to cases much more severe than theirs, and if they feel really sad about losing all their money then that’s just a perfectly normal emotion under the circumstances.

(if anyone asks why there are psychiatrists, the psychiatrists will say they’re sticking around to treat anyone who believes in mental illness, which is a delusion, and incidentally the only delusion that exists. Secretly the psychiatrists will still treat anybody who comes to them, they’ll just make them swear an oath of secrecy first. “Doctor patient confidentiality” will get redefined to mean that the patient has to keep it confidential that doctors exist.)

I’m not sure if this culture would have more or less mental illness than our own. But we’re trying the opposite experiment now, so I guess we’ll get to see how that turns out.