Book Review: First Sixth Of Bobos In Paradise

I.

David Brooks’ Bobos In Paradise is an uneven book. The first sixth is a daring historical thesis that touches on every aspect of 20th-century America. The next five-sixths are the late-90s equivalent of “millennials just want avocado toast!” I’ll review the first sixth here, then see if I can muster enough enthusiasm to get to the rest later.

The daring thesis: a 1950s change in Harvard admissions policy destroyed one American aristocracy and created another. Everything else is downstream of the aristocracy, so this changed the whole character of the US.

The pre-1950s aristocracy went by various names; the Episcopacy, the Old Establishment, Boston Brahmins. David Brooks calls them WASPs, which is evocative but ambiguous. He doesn’t just mean Americans who happen to be white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant - there are tens of millions of those! He means old-money blue-blooded Great-Gatsby -villain WASPs who live in Connecticut, go sailing, play lacrosse, belong to country clubs, and have names like Thomas R. Newbury-Broxham III. Everyone in their family has gone to Yale for eight generations; if someone in the ninth generation got rejected, the family patriarch would invite the Chancellor of Yale to a nice game of golf and mention it in a very subtle way, and the Chancellor would very subtly apologize and say that of course a Newbury-Broxham must go to Yale, and whoever is responsible shall be very subtly fired forthwith.

The old-money WASPs were mostly descendants of people who made their fortunes in colonial times (or at worst the 1800s); they were a merchant aristocracy. As the descendants of merchants, they acted as standard-bearers for the bourgeois virtues: punctuality, hard work, self-sufficiency, rationality, pragmatism, conformity, ruthlessness, whatever made your factory out-earn its competitors.

By the 1950s they were several generations removed from any actual hustling entrepreneur. Still, at their best the seed ran strong and they continued to embody some of these principles. Brooks tentatively admires the WASP aristocracy for their ethos of noblesse oblige - many become competent administrators, politicians, and generals. George H. W. Bush, scion of a rich WASP family, served with distinction in World War II - the modern equivalent would be Bill Gates’ or Charles Koch’s kids volunteering as front-line troops in Afghanistan.

At their worst, they mostly held ultra-expensive parties, drifted into alcoholism, and participated in endless “my money is older than your money” dick-measuring contests. And they were jocks - certainly good at lacrosse and crew, but their kids would be much less likely than modern elites’ to become a scientist, professor, doctor, or lawyer. Not only that, they were boring jocks - they stuck to a few standard rich people hobbies (yachting, horseback riding) and distrusted creativity or (God forbid) quirkiness. Their career choices were limited to the family business (probably a boring factory with a name like Newbury-Broxham Goods), becoming a competent civil service administrator, or other things along those lines.

The heart of the WASP aristocracy was the Ivy League. I don’t think there are good statistics, but until the early 1900s many (most?) Ivy League students were WASP aristocrats from a few well-known families. Around 1920 the Jews started doing really well on standardized tests, and the Ivies suspended standardized tests in favor of “holistic admissions” to keep them out and preserve the WASPishness of the elite. All the sons (and later, daughters) of the WASPs met each other in college, played lacrosse together, and forged the sort of bonds that make a well-connected and self-aware aristocracy.

Around 1955 (Brooks writes, building on an earlier book by Nicholas Lemann) Harvard changed their admission policy. Why? Partly a personal decision by Harvard presidents James Conant, and Nathan Pusey, who sincerely believed in meritocracy. And partly because Harvard’s Jewish quota was becoming unpopular, as increased awareness of the Holocaust made anti-Semitism déclassé. Conant and Pusey decided to admit based on academic merit (measured mostly by SAT scores). The thing where Harvard would always admit WASP aristocrats because that was the whole point of Harvard was relegated to occasional “legacy admissions”, a new term for something which was now the exception and not the rule. Other Ivies quickly followed.

Brooks on the consequences:

In 1952, most freshmen at Harvard were products of . . . the prep schools of New England (Andover and Exeter alone contributed 10% of the class), the East side of Manhattan, the Main Line of Philadelphia, Shaker Heights in Ohio, the Gold Coast of Chicago, Grosse Pointe of Detroit, Nob Hill in San Francisco, and so on. Two-thirds of all applicants were admitted. Applicants whose fathers had gone to Harvard had a 90% admission rate. The average verbal SAT score for the incoming men was 583, good but not stratospheric. The average score across the Ivy League was closer to 500 at the time.

Then came the change. By 1960 the average verbal SAT score for incoming freshman at Harvard was 678, and the math score was 695 - these are stratospheric scores. The average Harvard freshman in 1952 would have placed in the bottom 10% of the Harvard freshman class of 1960. Moreover, the 1960 class was drawn from a much wider socioeconomic pool. Smart kids from Queens or Iowa or California, who wouldn’t have thought of applying to Harvard a decade earlier, were applying and getting accepted . . . and this transformation was replicated in almost all elite schools. At Princeton in 1962, for example, only 10 members of the 62-man football team had attended private prep schools. Three decades earlier every member of the Princeton team was a prep school boy.

There was a one-or-two generation interregnum where the new meritocrats silently battled the old WASP aristocracy. This wasn’t a political or economic battle; as a war to occupy the highest position in the class hierarchy, it could only be won through cultural prestige. What was cool? What was out of bounds? What would get printed in the New York Times - previously the WASP aristocracy’s mouthpiece, but now increasingly infiltrated by the more educated newcomers?

II.

The meritocrats didn’t exactly have a culture of their own to bring to the fight. They were a haphazard faction thrown together by 1950s college admissions policies. But their links to academia let them lift the pre-existing culture of the intelligentsia and bohemians.

I’d never really understood the idea of “intelligentsia” before. I knew it meant the class of smart people, but eg English professors never seemed like a substantially different class than anyone else. Brooks says this isn’t a coincidence; the modern upper class copied and absorbed the intelligentsia, ending their existence as a separate group.

But Brooks focuses more on the bohemians - beatniks and starving artists who voluntarily dropped out of the rat race to pursue their passion. Again, it’s hard to identify these people as a separate group today. Brooks says they were a lot more noticeable before the upper class ate them and stole their skin.

These groups had evolved alongside and in opposition to the aristocracy. Their values were anti-capitalist - sometimes in the sense of being outright Marxists, but always in the sense of contempt for the boorish pursuit of money or status. To the intelligentsia and bohemians, the suburban white-picket-fence two-point-five-children lifestyle was infinitely contemptible compared to a passionate commitment to suffer for art or politics or erudition or whatever; they had spent the past two hundred years harping on this theme in approximately every novel ever written. The new meritocrats adopted these ideas as rallying cries for their cultural crusade against the bourgeois WASPs.

At some point (says Brooks) the meritocrats won and became the new elite. Their anti-bourgeois ideas became the foundation of our modern values. But part of the elites’ job is to run the financial system, and another part is to enjoy being very rich. This was a bad match for bohemian anti-bourgeois values, so they added some layers of irony, detachment, and misdirection.

A meritocrat in good standing must be (for example) a quirky, free-spirited person who happens to have a passion for banking. And in the course of pursuing this passion, they happen to have made $300 million as the CEO of Amalgamated Bank. They didn’t become CEO in order to make the $300 million. They became CEO because they were passionate about transforming banking and expanding its reach to underrepresented minorities.

And they certainly didn’t spend the $300 million on a mansion in a ritzy part of New York with well-manicured grounds and legions of servants. They spent it on a rustic cabin by Lake Tahoe made from locally-sourced pine. Sure, it happened to be 20,000 square feet and have an IMAX-sized media room. But that wasn’t why they got it. They got it so they could commune with nature and be sensitive. They plan to decorate it with woven handicrafts by their favorite Native American artisans (of course they have favorite Native American artistans! They’re not barbarians!) and use it as a “home base” as they pursue their passion of white water rafting.

All of this is so natural to our generation that it’s almost jarring for Brooks to point out the layers of misdirection. Native American handicrafts are - well, it would be offensive to call them “bad” - but they’re clearly not someone using all the technological power of society to create maximally dazzling and beautiful things. In some sense, they’re valuable in proportion to the degree to which they convey poverty; for best effects, a handicraft blanket should claim to be exactly like the one that the artisan’s great-great-grandmother might have woven in her mud hut on the reservation. They’re the opposite of typical unironic rich-person things like “giant intricately carved marble altarpiece with gold trim covered with Baroque paintings”. They signal “look how down to earth I am, buying peasant handicrafts from marginalized groups”. Or “I might be a bank CEO making $300 million, but it’s not about the money.”

But (Brooks continues) these people are elite and do insist on playing the usual elite signal games. Your particular Native American blanket might have been made by the most famous Native artisan, using only heirloom wool sustainably harvested from free-range sheep raised on traditional farms run by indigenous people of color. If your guests have any class, they will see the blanket, recognize it, and know all of that. Otherwise, you’ll have to subtly hint at it until they get the point. All of this signals a combination of:

-

sensitivity

-

compassion

-

allegiance to trendy causes

-

allegiance to the new meritocrat aristocracy against the old WASP one

-

enough free time and intelligence to know the intricacies of the system

-

not being the sort of money-obsessed WASP capitalist who would buy the baroque gold altar

-

but you do coincidentally happen to be rich enough that you can afford the absolute best handicraft blanket, made by a famous artisan

Pretty good for a blanket! And the white-water rafting hobby signals you’re a quirky fun-loving adventurous person with a personality, and not just a boring business-obsessed . . .

. . . you get the picture. You can see the point where this is going to segue into the remaining avocado-toast-related five-sixths of the book.

III.

Still, Brooks takes the change-of-aristocracies hypothesis pretty seriously. For example, he writes:

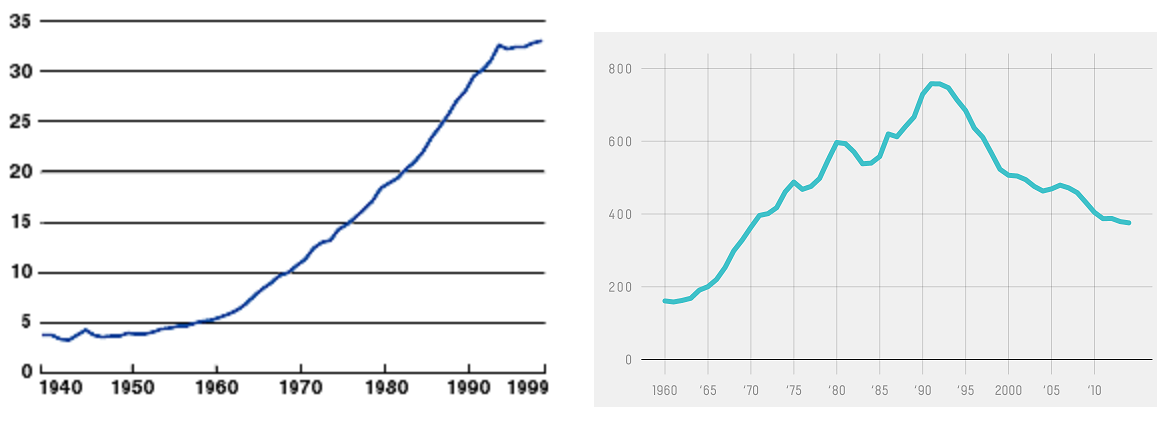

[The meritocrats’] efforts to tear down the old customs and habits of the previous elite was not achieved without social cost. Old authorities and restraints were delegitimized. There was a real, and to millions of people catastrophic, breakdown in the social order, which can be measured in the stunning rise in divorce, crime, drug use, and illegitimacy rates.

He’s right, of course, that there was a stunning rise in divorce, crime, drug use, and illegitimacy rates around this time.

Left: percent of births to unmarried women (source). Right: violent crime victimization rate per 100,000 people (source).

Left: percent of births to unmarried women (source). Right: violent crime victimization rate per 100,000 people (source).

These are the same data purportedly explained by the lead-crime hypothesis , where leaded gasoline poisoned young people’s brains and made them more impulsive. Last I checked this hypothesis had survived the replication crisis pretty well and continued to seem plausible. But Brooks’ theory is among the best alternatives I’ve heard.

Brooks kind of drops that paragraph in there and runs, as if he hadn’t just proposed a bold and controversial explanation for one of the most important social trends of the century. In the same spirit, I want to gesture at some other mysteries and concepts that I feel tempted to throw Brooks’ theory at:

-

Whither Tartaria? Around World War II, US civic architecture changed from colorful, ornate, old-fashioned looking buildings to brutalist concrete cubes or sleek glass modernist arrangements, even though most Americans continue to prefer the old-fashioned style; other art forms showed similar transitions at different times. Brooks’ theory suggests that the old-fashioned buildings were the preferred architecture of the WASP aristocracy, and the new architecture is the signaling equivalent of Native American handicraft blankets.

-

Partisan polarization. I don’t think this is the full story, maybe not even a big part of the story, but some of the story could be that WASP aristocrats were the natural head of the Republican Party. Or, at the very least, they were a reality anchor and Strategic Classiness Reserve. As their power gradually declined, the party was left headless (with the blue-blooded Bush dynasty playing Canute trying to hold back the waves). When working-class Republicans lost their upper-class allies, their natural choice was hostility to all elites, leading to the class-based politics of today.

-

Seeing Like A State and high modernism. Brooks namedrops Seeing Like A State as the quintessential meritocrat book and high modernism as the quintessential meritocrat bogeyman. High Modernism was something like the legitimizing ideology of the WASP aristocracy: we are great because we have raised shining skyscrapers, blasted railways through mountains, and built giant eternally-churning factories. As part of their cultural revolt, the meritocrats had to ritually humiliate all of this, which made them adopt as their legitimizing ideology a James Scott / Jane Jacobs - esque perspective of “skyscrapers disrupt the social fabric and blasting tunnels sounds environmentally unfriendly, how about some nice locally-sourced organic food?” He who has ears to hear, let him hear.

-

The debate around meritocracy. I previously wrote that it was hard to be against meritocracy, in that the alternatives - cronyism, nepotism, titled nobility - seemed worse. Bobos helps provide concrete details. The WASP aristocracy in fact seems bad to me; a lot of them really were arrogant boors who spent most of their energy conspicuously consuming and yachting. But if we grant a long chain of conjectures, they seemed to be better at some aspects of leading the country than their meritocratic successors. Why? Is there a simple patch, or is meritocracy inherently dangerous?

-

The Rise And Fall Of Culture Wars: I previously attributed secular changes in American culture to something like the barberpole theory of fashion: being right-wing was fashionable in the early 20th century. Then it became the symbol of a stodgy uncool establishment. By the 1960s, being a progressive hippie was fashionable. Today, being a progressive hippie seems like the symbol of a stodgy uncool establishment. And right on track, rebellious young people are becoming “alt-right”, a group with some suspicious similarities to the hippies (distrust authority, believe conspiracy theories, freak out over processed food, adopt paganism and weird spirituality, etc). So I was wondering if the right and left poles might just flip, over and over, in a long-term secular cycle. Brooks says that’s not what happened at all, and the 1950s-to-60s flip was a one-time event caused by a change in Ivy League admissions. If true, tragic news for today’s “Dimes Square” set.

-

What’s up with college admissions. I previously didn’t understand how pre-meritocracy colleges selected students. Brooks’ idea of the aristocratic establishment helps explain this. It also makes me understand why Ivies are so unwilling to admit more Asians despite their suppposed anti-racist principles. They consciously think of themselves as the gatekeeper of a US elite class, and having a 50% Asian ruling class in a 5% Asian country would be really jarring. Harvard might worry that this wouldn’t be great for the Asians themselves, who would face increased resentment. Or they might fear it would threaten the narrative of “all races are exactly alike except for how much discrimination they face”. Or they might worry that, faced with the prospect of a 50% Asian ruling class, America would say “no thanks” and come up with some other way to select their elites, costing the Ivies their monopoly on the process.

-

Paul Fussell’s Class X. At the time I thought this reference was jarring; Fussell starts out as an equal-opportunity satirist, making fun of every class alike. But then he says actually there are some pure perfect people without any foibles, and goes on to describe what sounds like the normal upper-middle class he probably belongs to. Charitably when Fussell wrote his book back in the 80s, there were still real bohemians, or at least he could remember a time when there were. Now all the features of bohemia have been reprocessed into generic upper-middle-class markers.

-

Fuzzy trad ideas of “values” mattering. Brooks already hints at this in his discussion of the crime / illegitimacy boom. I was previously suspicious of these explanations because it was hard to come up with a locus for “values”. Trends this big couldn’t be explained by individual values, but they didn’t quite seem like national values either - at least not the kind that could be budged with public awareness campaigns and feel-good support-our-values Disney movies. Brooks suggests the ruling class as the repository of values, and then lets values change suddenly because of a change in ruling classes.

One final note: Brooks’ neologism for the new meritocrats, “Bobos”, stood for bourgeois bohemians. It was cute but never caught on. I would say its closest modern equivalent is “bluechecks” (this is a a vast improvement over the earlier term “Cathedral”, since it doesn’t imply having read Moldbug). Alas, Elon Musk ruined it; I can only hope lightning strikes a second time and we get some equally descriptive moniker.

And speaking of Elon: every true silicon-blooded techie dreams of a world with no ruling class. A world where DeFi algorithms replace bankers, prediction markets replace “thought leaders”, and something something Khan Academy handwave bootcamp something something replaces the Ivy League. This is a beautiful utopian vision, which means it will never happen. More realistically, might techies replace traditional meritocrats as the ruling class? I think this was plausible around 2015, then fizzled out. Partly it fizzled because the New York Times , eternal mouthpiece of the establishment, noticed the situation and played defense effectively. Partly it failed because the meritocrats sort of took over Silicon Valley, and even though they don’t own everything yet, they do own enough to prevent it from organizing into a real counterelite. And partly it failed because the specter of Trump convinced lots of different elites to close ranks around the bluechecks as heroic defenders of democracy. I’m currently bearish on the whole project.

But if Brooks is right, Conant/Pusey’s fateful (and at the time unheralded) decision to open up Ivy admissions showed just how fragile aristocracies can be. Maybe some opportunity will arise where it is least expected.

Related:

-

Recent Quillette review of Bobos , I noticed it halfway through writing this but tried not to let it influence my thinking too much