Book Review: How Asia Works

What was the best thing that ever happened? From a very zoomed-out, by-the-numbers perspective, it has to be China’s sudden lurch from Third World basketcase to dynamic modern economy. A billion people went from starving peasants to the middle class. In the 1960s, sixty million people died of famine in the Chinese countryside; by the 2010s, that same countryside was criss-crossed with the world’s most advanced high-speed rail network, and dotted with high-tech factories.

And the best thing that ever happened kept happening, again and again. First it was Japan during the Meiji Restoration. Then it was Korea and Taiwan in the 1960s. Then China in the 90s. Now Vietnam and others seem poised to follow.

(fun trivia question: ignoring sudden oil windfalls, what country has had the highest percent GDP growth over the past 30 years? Answer, as far as I can tell: the People’s Democratic Republic of Laos.)

There was nothing predetermined about this. These countries started with nothing. In 1950, South Korea and Taiwan were poorer than Honduras or the Congo. But they managed to break into the ranks of the First World even while dozens of similar countries stayed poor. Why?

Joe Studwell claims this isn’t mysterious at all. You don’t have to bring in culture, genetics, or anything complicated like that. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, etc, just practiced good economic policy. Any country that tries the same economic policy will get equally rich, as China and Vietnam are discovering. Unfortunately, most countries practice bad economic policy, partly because the IMF / World Bank / rich country economic advisors got things really wrong. They recommended free markets and open borders, which are good for rich countries, but bad for developing ones. Developing countries need to start with planned economies, then phase in free market policies gradually and in the right order. Since rich country economists kept leading everyone astray, the only countries that developed properly were weird nationalist dictatorships and communist states that ignored the Western establishment out of spite. But now the economic establishment is starting to admit its mistakes, giving other countries a chance to catch up.

How Asia Works is Studwell’s guide to good economic policy. He gives a three-part plan for national development. First, land reform. Second, industrial subsidies plus export discipline. Third, financial policy in service of the first two goals.

1. Land Reform

Land reform means taking farmland away from landlords and giving it to peasant farmers.

Undeveloped countries are mostly rural (for example, Korea was about 80% rural in 1950). Most people are farmers. Usually these countries are coming out of feudalism or colonialism or something and dominated by a few big landowners. In one region of the Philippines (Studwell’s poster child for doing everything wrong) 17 families control 78% of farmland. Landowners hire peasants to work the land, then take most of the profit.

This system is immiserating and soul-crushing:

It was William Hinton, an American Marxist writer conducting research in the 1940s, who produced the classic outsider-insider’s tale of life in a Chinese farming village [in] Shanxi province. Hinton wrote about the mundane realities of death by starvation during the annual ‘spring hunger’ when food reserves ran out, and of the slavery (mostly of girls), landlord violence, domestic violence, usury, endemic mafia-style secret societies and other assorted brutalities that characterised everyday life. One of the most striking aspects was the attention paid to faeces, the key fertiliser. Children and old people constantly scoured public areas for animal droppings. Landlords demanded that day labourers defecate only in their landlords’ privies; out-of-village labourers were preferred by some because they could not skip off to their own toilets.

And:

In the 1920s, when 85 per cent of Chinese people lived in the countryside, life expectancy at birth for rural dwellers was 20-25 years. Three-quarters of farming families had plots of less than one hectare, while perhaps one-tenth of the population owned seven-tenths of the cultivable land. As in Japan, there were few really big landlords, but there was sufficient inequality of land distribution and easily enough population pressure to induce high-rent tenancy and stagnant output.

A rather typical landlord of the era was Deng Wenming, father of future Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, who owned ten hectares in Paifang village in the hinterland of Chongqing in Sichuan province. Deng Wenming lived in a 22-room house on the edge of his village and leased out two-thirds of his fields. He, like so many other landlords, was not a man of limitless wealth. But he controlled the land of more than half a dozen average families.

R.H. Tawney, the British economic historian, wrote after a visit to China in the late 1920s that the precariousness of Chinese agriculture was such that: ‘There are districts in which the position of the rural population is that of a man standing permanently up to the neck in water, so that even a ripple is sufficient to drown him … An eminent Chinese official stated that in Shanxi province at the beginning of 1931, three million persons had died of hunger in the last few years, and the misery had been such that 400,000 women and children had changed hands by sale.’

But it’s not just a humanitarian problem, it’s an economic one. Landlords want to extract as much as possible from tenants. When they succeed, tenants have no extra money to invest in improving their land (and no incentive to improve their land, since the landlord would just take the extra). Although in theory a self-interested but clever landlord could come up with some incentive scheme to make peasants improve land, in practice self-interested landlords can make more money faster by various shady lending practices or by buying up more land, and they never get around to yield-improvement schemes.

When peasants receive their own small plot of land, they start figuring out how to improve it. The difference between cursory land-tilling vs. an inventive peasant family trying to maximize yields on their small plot is huge Studwell uses the analogy of the hobbyist gardener vs. the giant commercial farmer. The hobbyist gives loving care to every single plant, hand-weeds their plot, arranges pots and planters and trellises and poles in the right positions, and knows weird tricks like intergrowing tall plants that produce shade and smaller plants that thrive in it. Meanwhile, the giant commercial farmer just runs his tractor over the land and calls it a day. As a result, the gardener’s plot is much more productive; Studwell calculates that a carefully-tended garden in the US might produce $16.50 per square meter per year; a commercial farm would produce $0.25. This doesn’t mean the commercial farmer is doing anything wrong! He ends up making much more than the gardener, because he has an entire giant farm; it would be impossible to tend the whole farm as carefully as the gardener tends his tiny plot. Both are maximizing a certain type of efficiency: the gardener is treating labor as cheap and maximizing yield per unit land; the farmer is treating land as cheap and maximizing yield per unit labor.

Farming when land is cheaper than labor, vs. farming when labor is cheaper than land

Farming when land is cheaper than labor, vs. farming when labor is cheaper than land

Land reform shifts the dynamic from landlords who act like commercial farmers to freeholders who act like gardeners. Asia is at no risk of running out of people, so treating labor as cheap and maximizing yield per unit land is the right choice. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China all implemented land reform at the beginning of their successful development pathways, and all four countries saw yields per hectare increase by 40 - 70%.

(China messed up by later switching to large-scale collective farming, which is the opposite of what you want at this developmental stage. And if this is starting to remind you of James Scott, remember that his day job is studying Asian peasant farmers.)

Increased rice yields aren’t as sexy as electric cars or semiconductors, but Studwell considers this step absolutely essential. First, this early in development, agriculture is most of your economy, so changes to agriculture are a big deal. Second, once you have more than enough crops to feed your people, you can export the rest and get the valuable foreign currency that you’ll need to buy factory parts and stuff. Third, if you don’t get agriculture right, your population might buy some of their luxury crops from foreign countries, depleting your valuable foreign currency reserves. Fourth, the more agriculture you have, the easier it will be for people to move to the cities and do industry. Fifth, at the beginning of industrialization your country’s industries will be terrible, the main way they’ll sell anything at all is having a captive customer base behind your tariff wall, and the best captive customer base is successful small farmers who want to buy tractors or whatever.

But even beyond this, Studwell talks up the almost spiritual benefits of land reform. In a typical land reform measure, an equal amount of land gets allotted to every peasant family. This is about as close as anything ever comes to the completely fair starting position that eg John Locke liked to fantasize about. Everyone gets to work for themselves in their own little small business, reaping the consequences of their own decisions. The generation who grow up immediately after a land reform tend to be thrifty, hard-working, honest, and civic-minded. They go on to found all of the giant world-spanning Toyota-style companies you get in the next round of development. Maybe this is just a coincidence; most people are farmers, and most farmers are affected by land reform, and the land-reform stage of the development pathway is separated by the found-giant-companies stage by about a generation. But Studwell thinks it’s more than this, and maybe it’s more than a coincidence that Asia and America have come to fetishize the virtues of small farmers in pretty much the same way.

Despite all these benefits, land reform rarely happens. Landlords naturally resist expropriation, and no country at this stage has the money to pay them market value. The Asian countries got their land reform through convoluted pathways. Japan’s happened first in the Meiji Restoration, but didn’t stick; the final version was rammed through by Douglas MacArthur, who acted as a dictator and didn’t care what Japanese elites thought. China’s happened under communism, and South Korea’s and Taiwan’s happened as part of an American-led effort to defuse the appeal of communism by giving peasants and workers an unusually fair deal under capitalism.

The American efforts owe a lot to US diplomat Wolf Ladejinsky, one of the heroes of this book. He was a Russian immigrant to America whose experiences under communism gave him a better idea what peasants wanted than most of his colleagues, and he pushed for land reform when everyone else thought it sounded too communist. His work was crucial in East Asia, but the US establishment sidelined him before he could influence the rest of the world.

How Asia Works ‘s success stories are always Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China. Its foils are always Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. These last three countries resisted calls for land reform, sometimes violently (when a Thai economist published a study saying land reform was needed, the king responded by banning the study of economics!) But as usual, the Philippines takes last place. It passed a series of laws that had “LAND REFORM” in the title, but all managed to be completely useless. In particular, they often said that landlords had to give workers their land, or some other mutually-agreeable concession of equal value. Landlords were legally savvier than tenants, and had nearly unlimited power over them, and the Filipino government was too corrupt and useless to monitor any of this, so landlords found ways to get workers to agree to various things which were legally worker ownership but realistically meaningless. According to a 2007 survey, “seven out of ten ‘beneficiaries’ of land reform on the island of Negros said they were no better off than before reform”. Filipino farming remains centralized and low-yield.

In contrast, in Japan land reform was done by village committee with landlords in a tiny minority; in Taiwan, they bought out the landlords with government bonds that quickly became nearly worthless; in China, they murdered the landlords in cold blood.

Studwell says land reform is absolutely vital for development:

Klaus Deininger, one of the world’s leading authorities on land policy and development, has spent decades assembling data that show how the nature of land distribution in poor countries predicts future economic performance. Using global land surveys done by the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), he has worked out that only one significant developing country has managed a long-term growth rate of over 2.5 per cent with a very unequal distribution of land. That country is Brazil, the false prophet of fast growth which collapsed in a debt crisis in the 1980s in large part because of its failure to increase agricultural output. Deininger’s two big conclusions are that land inequality leads to low long-term growth and that low growth reduces income for the poor but not for the rich. In short, if poor countries are to become rich, then the equitable division of land at the outset of development is a huge help. Japan, Korea and Taiwan put this in place.

Unfortunately, it’s not on the table anymore, which means we might not see many more East Asian - style economic miracles:

Will we witness an economic transformation like Japan, Korea, Taiwan or China’s again? The answer is quite possibly not, for one simple reason. Without effective land reform it is difficult to see how sustained growth of 7-10 per cent a year - without fatal debt crises - can be achieved in poor countries. And radical land reform, combined with agronomic and marketing support for farmers, is off the political agenda. Since the 1980s, the World Bank has instead promoted microfinance, encouraging the rural poor to set up street stalls selling each other goods for which they have almost no money to pay. It is classic sticking-plaster development policy. The leading NGO promoting land reform, US-based Landesa, is today so pessimistic about the prospects for further radical reforms in the world’s poor states that it concentrates its lobbying efforts on the creation of micro plots of a few square metres. These plots supplement the diets and incomes of rural dwellers who work in otherwise unreformed agricultural sectors. From micro interventions, however, economic miracles will not spring.

2. Industrial Policy and Finance

East Asian countries got rich by manufacturing. First it was “Made in Japan”, then “Made in Taiwan”, then “Made in China”. At first each label was synonymous with low-quality knockoffs. Gradually they improved, until now “Made in Japan” has the same kind of prestige as Germany or Switzerland, and even China is losing some of its stigma.

Not every rich country gets rich by manufacturing. Studwell divides successful countries into three groups. First, small financial hubs, like Singapore, Dubai, or Switzerland. This is good work if you can get it, but it really only works for one small country per region; you can’t have all of China be “a financial hub”. In the 1980s, everyone was so impressed with Singapore and Hong Kong that they became the go-to models for development, and people incorrectly recommended liberal free market policies as the solution to everything. But the Singapore/Hong Kong model doesn’t necessarily work for bigger countries, and most of the good financial hub niches are already filled by now.

Second, “high-value agricultural producers”. Studwell gives Denmark and New Zealand as examples. Again, these countries are very nice. But they also tend to be small and sparsely populated, and they also don’t scale. New Zealand’s biggest export category is “dairy, eggs, and honey”. Imagine how much honey you would have to eat to lift China out of poverty that way. It would be absolutely delicious for a few years, and then we would all die of diabetes.

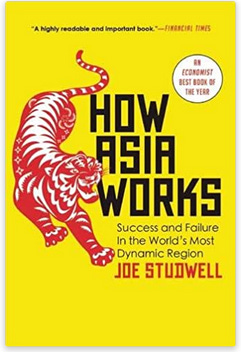

Third, manufacturing, eg everyone else. Every big developed country went through its manufacturing phase. Britain, Germany, and America all passed through an era of sweatshops, smokestacks, and steel. Most developed countries gradually leave that phase, switch to a services-based economy, and offshore some of the worse jobs to places with cheaper labor. But they can’t skip it entirely.

England in the 19th century, around the time Blake wrote of “dark satanic mills”

England in the 19th century, around the time Blake wrote of “dark satanic mills”

Kawasaki, Japan in 1970 (source)

Kawasaki, Japan in 1970 (source)

| [](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa24aedc3-8b99-4128-8a0f-2654cfadec1e_1280x720.jpeg)China today. Or maybe not, it’s hard to tell. |

And every big developed country that passed through a manufacturing phase used tariffs (except Britain, which industrialized first and didn’t need to defend itself against anybody). Economic planners like Friedrich List in Germany and Alexander Hamilton in the United States realized early on that British competition would stifle the development of native industry without government protection. Once their industries were as good as Britain’s, they removed their tariffs, which was the right move - but they never would have been able to reach that level without protectionism.

Imagine having to start your own car company in Zimbabwe. Your past experience is “peasant farmer”. You have no idea how to make cars. The local financial system can muster up only a few million dollars in seed funding, and the local manufacturing expertise is limited to a handful of engineers who have just returned from foreign universities. Maybe if you’re very lucky you can eventually succeed at making cars that run at all. But there’s no way you’ll be able to outcompete Ford, Toyota, and Tesla. All these companies have billions of dollars and some of the smartest people in the world working for them, plus decades of practice and lots of proprietary technology. Your cars will inevitably be worse and more expensive than theirs. Every country that’s solved this problem and started a local car industry has done so by putting high tariffs on foreign cars. Locals will have to buy your cars, so even if you’re not exactly making a profit after a few years, at least you’re not completely useless either.

This will become a problem if it shelters companies from competition; they’ll have no incentive to improve. Successful East Asian countries avoided this outcome by having many local car companies. The most successful ones went a bit overboard with this:

In the Korea of 1973 - which at the time boasted a car market of just 30,000 vehicles per annum - government had offered protection and subsidies to not one but three putative makers of ‘citizens’ cars: HMC, Shinjin, and Kia. Inasmuch as the market was too small for one producer, the licensing of three companies was ridiculous. HMC posted losses every year from 1972 to 1978, despite very high domestic car prices. However, the government sanctioned multiple car makers not to make shot-term profits - which would have come much sooner to a monopoly manufacturer - but rather to force the pace of technological learning through competition.

In addition to domestic competition, these governments enforced “export discipline”. In order to keep their government perks (and sometimes in order to keep existing at all), companies needed to sell a certain amount of units abroad each year. At the beginning, they might have to sell for way below-cost to other equally poor countries. That was fine. The point wasn’t that any of this was a short-term economically reasonable thing to do. The point was to force companies to be constantly thinking about how to succeed in the “real world” outside the tariff wall. And the secondary point was to let the government know which companies were at least a little promising, vs. which ones were totally unable to survive except in a captive marketplace. If a company couldn’t export at least a few units, the government usually culled it off and gave its assets to other companies that could.

Aren’t there good free-market arguments against tariffs and government intervention in the economy? The key counterargument is that developing country industries aren’t just about profit. They’re about learning. The benefits of a developing-country industry go partly to the owners/investors, but mostly to the country itself, in the sense of gaining technology / expertise / capacity. It’s almost always more profitable in the short run for developing-world capitalists to start another banana plantation, or speculate on real estate, or open a casino. But a country that invests mostly in banana plantations will still be a banana republic fifty years later, whereas a country that invests mostly in car companies will become South Korea. The car company produces a big positive externality - in the sense of raising the country’s level of development - which isn’t naturally captured by the owners/investors. So development is a collective action problem. The country as a whole would be better off if everyone started car companies, but each individual capitalist would rather start banana plantations.

So the job of a developing country government is to try to get everyone to ignore profits in favor of the industrial learning process. “Ignore profits” doesn’t actually mean the companies shouldn’t be profitable. All else being equal, higher profits are a sign that the company is learning its industry better. But it means that there are many short-term profit opportunities that shouldn’t be taken because nobody will learn anything from them. And lots of things that will spend decades unprofitable should be done anyway, for educational value.

2b.

In 1961, General Park Chung-Hee took power after a military coup in South Korea. I don’t know much about Korean religion, but if some heavenly Scriptwriter wanted the perfect hero for an industrial development story, they might come up with someone who looked a lot like General Park.

After graduating college, he joined the occupying Japanese military, where he served in Japan’s drive to industrialize its occupied territories. By the time Japan was defeated and withdrew, he had absorbed all the economic knowledge of the only successful non-Western economic power up to that point.

But also:

…he was an amateur historian who specialised in the histories of rising powers. He was well read on German development, and followed closely that country’s swift, state-led re-industrialisation after the Second World War. He also knew in detail the stories of Sun Yat-sen, Turkey’s Kemal Pasha and Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser and their efforts to nurture modern, large-scale industries. Nine months after taking power in Korea, the peasant-born Park published a book of his own, Our Nation’s Path: Ideology for Social Reconstruction , which contained a road map for what Park described as ‘co-ordination and supervisory guidance, by the state, of mammoth economic strength’. The next year Park published The Country, the Revolution and I , with chapters on ‘The Miracle on the Rhine’ and ‘Various Forms of Revolution’ in which he discussed different historical revolutions from an economic and developmental perspective. (He always referred to his own coup as a revolution.)

Park pushed an odd mix of free competition and heavy economic planning:

He stressed that, as in Japan, the Korean state would do the planning while the private sector would lead the investment: ‘The economic planning or long-range development programme must not be allowed to stifle creativity or spontaneity of private enterprise,’ Park wrote. ‘We should utilise to the maximum extent the merits usually introduced by the price machinery of free competition, thus avoiding the possible damages accompanying a monopoly system. There can be and will be no economic planning for the sake of planning itself.’ He gave as his historical cue the co-opting of private capitalism by the Meiji oligarchs: ‘Millionaires… were allowed to enter the central stage, both politically and economically, thus encouraging national capitalism,’ he wrote. ‘The case of the Meiji imperial restoration will be of great help to the performance of our own revolution.’

Twelve days after taking power, General Park ordered his officers to imprison all of South Korea’s leading businessmen, then forced them to sign agreements promising to give the government all their property. Then he gave them all their property back and freed them. He wasn’t actually anti-business, quite the opposite. He just wanted everyone to know who was in charge.

Once he established the basic rules of the game, Park informed Korea’s businessmen that they were free to make as much money as they could so long as they stuck by the rules. Most of the businessmen were released from prison during 1961. But if they thought Park’s regime would ease off once they were out, it soon became clear that this was not the case. One early exchange that sent a crystal clear message occurred after the chief of Lucky-Goldstar (now known as LG), Koo In Hwoi, was released. One of Park’s colonels responsible for industrial policy told him to organise a foreign loan (which the government would guarantee) and technology transfer for a cable factory. When Koo tried to wriggle out of the task, pleading that he knew nothing about the cable business, the colonel told him that whereas he had been thinking of making Koo sort the whole thing out in a week, as a special dispensation he would let him do it in two weeks. Ten days later, Koo was sufficiently chastised to produce a technology transfer deal with a West German firm and the requisite financing arrangements. One of Korea’s richest businessmen had gotten the message.

One gets the impression that Park thought of great entrepreneurs and leaders the same way he thought of eg construction cranes. They were a useful tool which could be used to produce great things, and you would happily pay a lot of money to continue to have them. But you had to direct them at useful projects, otherwise they would be wasted.

Useful projects like making thousands of people form a giant picture of your face by holding up placards. What is it about Korean dictators?

Useful projects like making thousands of people form a giant picture of your face by holding up placards. What is it about Korean dictators?

Not that workers were treated any more leniently:

Each day workers at Pohang [steel factory] were lined up in front of the main, corrugated-iron site office and told that Japanese reparations money was being used for the project and that it was preferable to die rather than suffer the humiliation of wasting the money.

After doing this kind of thing long enough, you start to see results. When General Park seized power in 1961, South Korean GDP was less than 100 dollars per person. When he was assassinated in 1979, it was about $2000. But his influence lingered:

Korean bureaucrats were reading not the rising American stars of neo-liberal economics, or even Adam Smith, but instead [German development expert and tariff proponent] Friedrich List. The Korea and Taiwan scholar Robert Wade observed when he was teaching in Korea in the late 1970s that ‘whole shelves’ of List’s books could be found in the university bookshops of Seoul. When he moved to the Massachussetts Insitute of Technology, Wade found that a solitary copy of List’s main work had last been taken out of the library in 1966. Such are the different economics appropriate to different stages of development. In Korea, List’s ideas for a national system of development were being adapted to a country with a population far smaller than Germany’s or Japan’s, and with a mid-1970s GDP per capita on par with Guatemala. The ideas were implemented in the teeth of the worst international trading conditions for a generation featuring two unprecedented energy crises. It did not matter. Park motored on regardless. Each time the US, the World Bank and the IMF urged him to back away from his state-led industrial policy he agreed - and then did precisely nothing (or occasionally a very little ). Park was a leader of conviction, and his convictions were based in history.

By 2013, when Park’s daughter Geun-hye was elected president, the country’s GDP was almost $30,000 per capita.

2c.

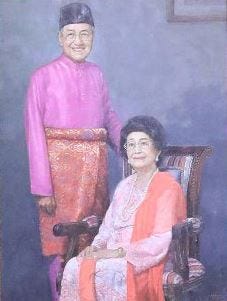

In contrast, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines never achieved this level of growth. Studwell focuses his attention on Malaysia, the country that tried hardest. In 1981, Malaysia’s new prime minister Mahathir bin Mohamed made a deliberate effort to imitate Japanese/Korean developmental success. Although he got a few things done, results could most charitably be described as “mixed”. Studwell blames a few things.

First, Mahathir didn’t enforce export discipline. “This not only engendered an acute balance of payments problem, it left Mahathir to make critical investment decisions without the market-based information that export performance provided to Park Chung-Hee. Instead of counting exports, Mahathir trusted his own judgment about the firms and managers he was backing. He tried to know more than the market.”

Second, instead of letting entrepreneurs compete, he tried to create state-backed monopolies. This made more sense given the small domestic market his companies were selling to, but it forced the state to pick winners and losers, and the state turned out to be bad at this. When the state-backed steel company floundered, Mahathir replaced the CEO with a guy who turned out to be kind of a con man.

Third, Mahathir let foreign partners lead the way, or get equity in Malaysian firms. Studwell thinks this was a bad decision. Sure, working with foreign companies who already have the technology you need seems like a good way to get a leg up. But they usually try to do all the exciting high-tech stuff themselves and just use you for menial labor. Remember, when you get a steel company to produce a million tons of steel, you’re mostly not buying steel, you’re buying learning. If a foreign company makes and runs the factory, they’re the ones learning more about steel, on your dime. Park Chung-Hee had a simple, straightforward strategy for dealing with foreign companies: partner with them only long enough to steal all of their technology. Malaysia tried actually partnering with them, and so a lot of foreign companies produced large parts of Malaysian goods and Malaysia barely benefitted.

Fourth, Mahathir was committed to affirmative action. Most of Malaysia’s businesspeople are from the Chinese or Tamil minority groups, and a lot of Malaysian politics is about trying to lift up the less successful Malay majority. This meant Mahathir had to support native Malay firms, native Malay entrepreneurs, etc. But this blocked him from using a lot of his best people. It also committed him to a more centralized strategy; he didn’t want to support the development of existing businesses, because existing businesses were owned by people of the wrong race. He didn’t want to let the free market pick winners, because it might pick people of the wrong race. This forced him to be more hands-on, and his government wasn’t up to the task.

Fun Mahathir Mohamad fact: all of this stuff happened during his first term, from 1981 to 2003. After losing, he bided his time for 15 years before retaking power from 2018 - 2020. By the end of his second term, he was 95, making him the oldest head of government in the world.

Fun Mahathir Mohamad fact: all of this stuff happened during his first term, from 1981 to 2003. After losing, he bided his time for 15 years before retaking power from 2018 - 2020. By the end of his second term, he was 95, making him the oldest head of government in the world.

Finally, he wanted to be exciting and high-tech. When he ordered the construction of Malaysia’s first steel plant, he wanted it to be more efficient than the best foreign factories. But number one, this required hiring foreign contractors to build it - there was no way Malaysia was going to build a super-efficient steel plant itself when it didn’t even know how to make regular steel plants. And second, the super-advanced technology crashed and burned, and the project had to be scaled back at great cost. Mahathir started a bunch of high-tech cyber investment parks, all of which failed when nobody in Malaysia was actually able to do high-tech-cyber stuff very well. Park Chung-Hee started with crappy steel mills and barely-functional cars and worked his way up.

The book blames most of this on Mahathir listening to McKinsey consultants and globalization advocates - especially Japanese theorist Kenichi Ohmae, author of The Borderless World. Ohmae was right that globalization would happen. He was even right that Japan - which at that point was a First World country - could benefit by taking part in it. But what works for developed countries isn’t right for developing ones, and at that point it was the wrong advice for Malaysia. During Park Chung-Hee’s 18 years in power, he increased his country’s GDP by a factor of 17; during Mahathir’s 22 years, ending in 2003, he barely doubled it.

3. Finance

Studwell devotes a separate chapter to finance, but it’s really a corollary of the industrial policy section. Developing country financial systems need to support industrial policy by preferentially offering great loans to industrial learning projects. This won’t work under a free market system. Under a free market system, banks will offer the best loans to whatever is most profitable, probably some short-term resource extraction scheme that nobody learns anything from.

Not only will the free market banks get it wrong, they’ll make it harder for the state banks to get it right. First of all, the free market banks will be giving entrepreneurs easy access to credit for short-term schemes, which will make the entrepreneurs less likely to go into industry. Second, ordinary savers will put their money into the free market banks, which can offer good interest rates (since they’re making profitable loans) instead of the state banks, which will offer low interest rates; this will deprive the state banks of capital. During Korea’s economic miracle, Korean banks offered savers negative interest rates; savers put their money in the banks anyway, because they had no good alternative.

All successful Asian countries have instituted strict capital controls to keep foreign money from flowing in and changing the incentives. Japan had capital controls until 1980, Korea until 1993, Taiwan until the late 1980s (also, breaching Taiwanese capital controls was “punishable by death”). China still has heavy capital controls, which not even cryptocurrency has made fully permeable.

On the other hand, all developed Asian countries opened their markets at some point. Studwell thinks this is good. He says that once you can compete on an even footing with everyone else, capital controls go from a bonus to a liability, and all the regular arguments in favor of free trade start to make sense again.

Aside from capital controls and a focus on industrial policy, Studwell doesn’t really care what kind of financial policy you have. The economic establishment recommends prudent borrowing, but he isn’t really seeing it. Malaysia borrowed very prudently and never really got anywhere. On the other hand, Korea’s borrowing was described as “crazed” and they did fine. China’s level of debt is frankly terrifying, but they seem to have pulled it off so far by growing faster than they borrowed, even though they borrowed a lot. It turns out you can pay back a lot of loans when your GDP doubles every few years.

4. Conclusions

This book was really convincing, but I don’t know much economic history so maybe convincing me is too easy. After Steven Pinker wrote How The Mind Works , Jerry Fodor wrote a counterbook called The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way. What would be in Asia Doesn’t Work That Way?

One basic version appears in State Development Planning: Did It Produce An East Asian Economic Miracle?. The author gives some theoretical reasons why planning can’t work, points out some serious mistakes made by planning boards, and notes that in 1970, Japan was considered the 7th freest economy in the world, Taiwan the 16th freest, and South Korea #31, which is still pretty good. Also, Hong Kong was #1, had very little state planning, and still did great. He argues that this is a standard free market success story, and that state planning mostly made things worse but luckily not worse enough to prevent a miracle.

I don’t find this too convincing. The theoretical arguments about planning (socialist calculation problem, necessity of price signals) make some sense, but East Asia used internal competition and export discipline to get around this; they weren’t planning in the sense of trying to second-guess the market. The development-as-coordination-problem frame makes it clearer why the usual free market arguments wouldn’t completely apply here. More relevantly, the recent success of China and Vietnam, which are not economically free by any stretch of the imagination (#100 and #128 on one index) make a strong argument that industrial planning without free markets can still succeed.

(though I agree the success of Hong Kong is awkward here, and I wish that Studwell had spent more time fleshing out his “some countries are just financial hubs and don’t count” position)

I think there are stronger counterarguments to Studwell scattered throughout journals that I haven’t quite figured out how to navigate and collect. The infant industry argument seems to be a going controversy within economics and not at all settled science. The picture is complicated by studies showing that countries with lower tariffs have had higher GDP growth since 1945. Studwell could respond that tariffs only work as part of a coherent and well-designed industrial policy; if you just tariff random things to protect special interests, it will go badly in exactly the way free marketeers expect.

But overall I think the book’s thesis is at least compelling, and I understand it’s supported by lots of people whose opinions I trust, like Noah Smith and Bill Gates. Pseudoerasmus, my usual go-to source for economic history opinions, doesn’t give a specific opinion of this book but seems to think a lot of its points are at least plausible.

Studwell does a good job casting doubt on a lot of alternatives to his theory. Lots of people tout parliamentary democracy, human rights, and rule of law as key to development success. But Japan industrialized under an emperor, Korea under a dictator, Taiwan under authoritarian nationalists, and China and Vietnam under communists. None of them had much in the way of human rights, and the level of rule of law was consistent with Park Chung-Hee imprisoning every single businessman in Korea just to get their attention. Probably you need a minimum level of all of these things to function at all - death squads going around burning random stuff is bad for business. But successful East Asian countries don’t seem to have had spectacular levels of these things, or even better than average.

He doesn’t have as clear an argument against geographic, biological, and cultural factors. Minus a sea or two, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and China are basically contiguous. It seems weird that all the countries with good policies would be right next to each other. Also, is it just a coincidence that Chinese / East Asian people in Malaysia and Singapore (and now the US) are known for being especially smart, rich, and good with money? Just a coincidence that these areas have hosted some of history’s greatest and richest civilizations? Don’t these push more in favor of the geographical/biological/cultural theories?

I’m not sure. It’s worth noting that Korea and Taiwan were both Japanese colonies, and heavily influenced by Japanese economic philosophy. This seems especially clear in the case of Korea, whose economic miracle was led by Park Chung-Hee, a former Japanese officer who had studied Japanese economic theory. It’s less obvious with Taiwan, which was occupied by Kuomintang unconnected to its Japanese colonial tradition. But of course the China of the time was also heavily influenced by Japan. Maybe the common factor among these three countries’ economic policies was the heavy Japanese influence. And then mainland China had lots of reasons to be influenced by them, especially by Taiwan, and then Vietnam was influenced by mainland China.

Or maybe it’s the land reform. China and Vietnam got land reform because they were communist, and Japan/Korea/Taiwan got it under an American policy of anti-communist pre-emption. I don’t know about other regions, but maybe none of them had a similar enough situation to overcome vested interests and get that passed.

The glorious history and Confucian culture might have mattered through the good policy? Japan/Korea/Taiwan weren’t completely corruption-free, but overall it was surprising how well their bureaucracies worked. Programs intended to reward companies that exported successfully really did reward companies that exported successfully, unlike in eg Malaysia where they rewarded companies based on connections or race. Ordinary citizens were surprisingly willing to go along with plans that required they work very hard in factories their entire lives and earn negative interest rates on their savings. Entrepreneurs mostly did as they were told instead of trying to cheat the system, and weren’t powerful enough to take over the government and torpedo the industrial plan in favor of one that let them make more profit. Overall, even if it was the good policy that made the difference, all the policy-makers involved deserve a lot of credit for implementing the policy fairly and efficiently and sticking to it even when it got hard.

One thing I appreciated about this book is that Studwell expects his audience to be classical liberals and takes care not to offend their (okay, my) sensibilities. He says again and again that he expects free-market-ish policies to be optimal for developed countries. He says again and again that certain aspects of free market policy, for example competition and entrepreneurship, are vital for the developing world. He treats his free market readers as reasonable people who are trying to do good economics but need to understand how the requirements of the developing world differ, and not as evil monsters who need to be shamed. So although both he and David Harvey make some of the same points about how the Washington Consensus in favor of free market reforms harmed developing countries, I felt like Studwell effectively explained where it went wrong and how to do better, whereas Harvey just sort of screamed that anyone who supported it was part of a conspiracy. I felt abused and confused after reading Harvey, I felt enlightened (and actually changed my mind) after reading Studwell.

But even though he puts it excruciatingly kindly, Studwell is kind of accusing the global economic establishment of impoverishing several dozen major countries. He goes through the recent history of Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines, and shows how in each case, the global economic establishment (especially the IMF and World Bank) convinced them not to protect infant industries, not to institute capital controls, and not to stress manufacturing too much. Then each of those countries suffered financial crises and their development stagnated. It really is striking how the countries that did the best were the ones that gave the world establishment the middle finger (unless of course this is cherry-picking and there are lots of big countries that followed IMF advice and did great). To whatever degree this is true, it belongs on the list of science failures that should keep us up at night, alongside all those people saying not to wear masks for COVID. Except that the COVID mistake lasted a few months and killed a 5-6 digit number of people, and the IMF advice lasted decades and kept hundreds of millions in poverty.

What now? Studwell uses the last chapter to warn China that its development model can only go so far. Dictatorship and state planning can lift a country from poor to middle-income, but so far everywhere that’s become truly rich has also been free and democratic. He doesn’t think that’s coincidence; it takes a more decentralized approach to explore the technological frontier than to play catch-up (see also Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction). How Asia Works was written in 2014, a more optimistic time, and I don’t know whether he still thinks this.

He concludes on a pessimistic note: the land reform -> industrial policy -> very late liberalization model followed by East Asia is the only thing that has ever worked at scale for catch-up development. But nobody seems interested in it anymore; either they’re still following bad advice to liberalize early, or they act like they “missed the boat” and have to try half-measures. He doesn’t see a lot of hope other than pushing countries towards least-bad policies, stopping the flow of bad advice, and seeing if it helps a little:

Will we witness an economic transformation like Japan, Korea, Taiwan or China’s again? The answer is quite possibly not, for one simple reason. Without effective land reform it is difficult to see how sustained growth of 7-10 per cent a year - without fatal debt crises - can be achieved in poor countries. And radical land reform, combined with agronomic and marketing support for farmers, is off the political agenda. Since the 1980s, the World Bank has instead promoted microfinance, encouraging the rural poor to set up street stalls selling each other goods for which they have almost no money to pay. It is classic sticking-plaster development policy. The leading NGO promoting land reform, US-based Landesa, is today so pessimistic about the prospects for further radical reforms in the world’s poor states that it concentrates its lobbying efforts on the creation of micro plots of a few square metres. These plots supplement the diets and incomes of rural dwellers who work in otherwise unreformed agricultural sectors. From micro interventions, however, economic miracles will not spring.

South-east Asia (like India) is a region in which serious land reform is off the political agenda, even if the farce that is the Philippine reform programme continues. Given this, can the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand do anything else to improve their economic performance? Most obviously they could make the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) work as a vehicle for effective industrial policy. There is no reason why the four core economies of ASEAN (and indeed Vietnam, the important economy omitted from this book) could not run an effective manufacturing infant industry policy in what is a market of 500 million people. But there is no sign of this happening. Rather than raising barriers and promoting exports to nurture local manufacturing enterprise, ASEAN is engaged in signing free trade agreements with industrially more developed states, including China. There is very little cohesion, or substantive dialogue, between the political leaders of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. And the considerable influence of the offshore financial centre of Singapore in ASEAN is developmentally deeply unhelpful. It is as if Switzerland or Monaco had been granted a seat at the table when post-war European industrial policy was being planned in the 1950s. South-east Asia remains a beacon for what not to do if you want economic transformation. Allow landlordism and scale farming despite the presence of vast numbers of underemployed peasants capable of growing more. Do not worry too much about export-oriented manufacturing, which can happily be undertaken by multinational enterprises. Leave entrepreneurs to their own devices. And proceed quickly to deregulated banking, stock markets and international capital flows, the true symbols of a modern state. That is how its politicians constructed the south-east Asian region’s relative failure.

The rich world cannot be expected to save poor countries from bad politicians. But the likes of Mahathir and Suharto were not so terrible. What seems most wrong in all this is that wealthy nations, and the economic institutions that they created like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, provided lousy developmental advice to poor states that had no basis in historical fact. Once again: there is no significant economy that has developed successfully through policies of free trade and deregulation from the get-go. What has always been required is proactive interventions - the most effective of them in agriculture and manufacturing - that foster early accumulation of capital and technological learning. Our unwillingness to look this historical fact in the face leaves us with a world in which scores of countries remain immiserated; and in which rural poverty nourishes terrorist groups that echo those suppressed in south-east Asian countries, but which now directly threaten the citizens of rich nations. It is not easy to implement the policies discussed in this book, especially land reform. However I repeat what others concluded after the Second World War: that to turn away from such policies indicates that the world is acceptable to us as it is. Take a look at south Asia, the Middle East and Africa, and ask yourself if it is.