Book Review: Modi - A Political Biography

I.

I have a friend who studied the history of fascism. She gets angry when people call Trump (or some other villain du jour) fascist. “Words have meanings! Fascism isn’t just any right-winger you dislike!” Maybe she takes this a little too far; by a strict definition, she’s not even sure Franco qualifies.

Anyway, I mention this because she says Narendra Modi, the current prime minister of India, is absolutely, literally, a fascist.

This is a strong claim, but Balakrishna Moonje helped found the precursor to Modi’s party. He went on a fact-finding trip to fascist Italy, met Mussolini, decided he had the right idea, and told the Indian papers that he wanted to:

“…imitate the youth movement of Germany and the Balilla and Fascist organisations of Italy. I think they are eminently suited for introduction in India, adapting them to suit the special conditions. I have been very much impressed by these movements and I have seen their activities with my own eyes in all details.”

So let’s at least say this isn’t the least fascist-inspired group around. It’s not that there aren’t extenuating circumstances. Indian independence movements of the time were fighting Britain, which made the fascist powers natural allies. And in 1934 when Moonje met Mussolini nobody had seen just how badly fascism could go. Still, not the sort of pedigree you want for your country’s ruling party.

So I thought I’d make Modi the next entry in the ACX Dictator Book Club (previously: Erdogan). The Internet recommended Andy Marino’s Modi: A Political Biography , and it seemed the least overtly hagiographical of the options Amazon gave me:

Alas, M:APB is absolutely a hagiography. The author begins by writing about how Modi let him ride with him in his private helicopter and gave him unprecedented access to have “open-ended conversations” about “every aspect of his life”. The cover promises an objective evaluation, but on page 2, the author notes that “Objectivity does not mean flying in the face of incontrovertible evidence”, adding that “Modi has been the subject of the longest, most intense - and probably the most vituperative - campaign of vilification.” Marino promises to replace this campaign with “a narrative that is balanced, objective, and fair - but also unsparingly critical of [Modi’s] foibles” - which is an interesting construction, given how it contrasts criticism with fairness - and also pre-emptively declares the flaws he will be criticizing “foibles”. I’m not sure we ever get around to the criticism anyway, so it doesn’t really matter.

I am still going to summarize and review this book, but I recommend thinking of it as Modi’s autobiography, ghost-written by Andy Marino. I hope to eventually find another book which presents a different perspective, and an update for the past six years (M:APB ends in 2014, right when Modi was elected PM). Until then, think of M:ABP as a look into how Modi sees himself, and how he wants you to see him.

II.

Narendra Modi wants you to see him as a fantasy novel protagonist.

He was born to a poor family in a mud house in a backwater village. As a child, he worked at his father’s stall, helping him sell tea. The book says that there were no early signs of greatness. Except: his village had a shrine in the middle of a crocodile-infested lake. On holy days, you had to perform a ritual at the shrine, but one day after a rainstorm the crocodiles were especially angry and nobody could make it. Young Narendra organized the villagers to beat pots and pans to distract the crocodiles, then swam across the lake himself, performed the rituals, and swam back unharmed. Everyone in the village declared that he would one day become a great leader, “or words to that effect”.

As a teenager, Modi spontaneously adopted ascetic habits. “First he gave up eating salt, then he gave up eating chilies, and even oil.” “No matter what the temperature is, he always takes baths in cold water”. He read and fell in love with the works of Swami Vivekananda, although only as “intellectual admiration of an ecumenical figure who made over Hinduism for modern purposes, revealing its kinship to other faiths through his enlightened liberalism”, because Narendra Modi Is Certainly Not Some Kind Of Religious Fanatic. He joined Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the aforementioned accused-of-fascism youth organization, because of “a feeling of duty and belonging in the widest sense”.

Then he learned his parents had arranged his marriage to a local girl years ago, when they were both children. He wasn’t up for this, both because of normal not-up-for-child-marriage reasons and (reading between the lines) because he thought of himself as committed to celibacy. When his parents refused to back down, he gathered all his possessions in a bag and ran off to the Himalayas to find Truth.

According to the book, “exactly what Narendra did between the ages of seventeen and nineteen, where he went and why, remains obscure”. Modi himself “smiles and waves away questions about those years of wandering”. Marino has done a little research, and finds that Modi asked to join several monasteries, all of which rejected him because he didn’t have a college degree (f@$king credentialism! Is there anywhere it hasn’t reached?) He visited sites related to Swami Vivekananda, presumably to appreciate how liberal and ecumenical they were. Also, at one point, he:

…found himself travelling via Siliguri, as far north-east as Guwahati or even further, and deep in a ‘remote jungle’. There, miles from civilization, he stumbled across a hermit or medicant with whom he struct up a friendship. The man was ‘very thin, it seemed that he had transparent skin’. There was little sense of urgency in Narendra’s journeying, and he spent about a month helping in the ascetic’s garden plot, spending time dicussing ‘spiritual matters’, before he decided to move on.

Finally - and I imagine this happening as the stereotypical scene where a man climbs a Himalayan peak to ask the master one question - one of the monks who Modi met revealed to him that he wasn’t destined for the spiritual life. Modi immediately realized this was true and went back to his home village. “[His mother] broke down and almost inarticulate, asked the sort of question a parent whose teenage son had stayed out too late would ask: ‘Where have you been?’ ‘The Himalayas,’ responded Narendra laconically.”

After spending “barely twenty-four hours” with his family, Modi went back to his local RSS office, where everyone knew him well, and asked if there was anything useful he could do in politics.

They made him an entry-level party apparatchik in the nearby city of Ahmedabad. Modi remembers:

If I was the person that cleans the car, I made sure to clean the car very nicely, so that even my boss thought: “That is a good boy, teach him to drive, he will be useful for our driving.” Then I become a driver. So basically, whichever assignment is given to me, at that point of time, I am totally involved in it. I never think about my past, I never think about my future.

III.

In 1975 the Emergency happened.

For thirty years, since its independence, India had been a socialist state. Not the cool kind of socialist where you hold May Day parades and build ten zillion steel mills. The boring kind of socialist where the government makes you get lots of permits, then taxes you really heavily, and nothing really ever gets done. “Even today the Representation of the People Act requires all Indian political parties to pledge allegiance not only to the Constitution but also to socialism.” The RSS and its collection of associated right-wing nationalist parties supported Hindu nationalism plus socialism. Their arch-enemy, the center-left-to-confused-mishmash Congress Party, supported secularism plus socialism. Non-socialism was off the table.

In unrelated news, there was a food shortage. Indians took to the streets protesting Prime Minister Indira Gandhi (no relation to Mahatma Gandhi). Gandhi was heavy-handed in crushing the protests, which caused more protests, one thing led to another, and finally Gandhi declared martial law, a period which has gone down in history as the Emergency.

Gandhi immediately moved to arrest all her political enemies and shut down all newspapers that criticized her. The RSS was one of Gandhi’s main enemies and had to go underground quickly. Gujarat became a center for the resistance. So Modi, as an official in Gujarat’s RSS, ended up right in the middle of this. He remained a paper-pusher, but now he was a paper-pusher for freedom , scheduling meetings of resistance leaders, maintaining a master list of safe houses and trusted operatives, and keeping lines of communication open.

During a capital-e Emergency even paper-pushers can have greatness thrust upon them, and Modi ended up with responsibilities way outside his formal job description:

Chhayanak Mehta tells of how, after Deshmukh’s arrest, it was discovered that the papers he was carrying were still with him. These contained plans for the future actions of the [resistance], and it was essential to somehow retrieve them. To this end, Modi planned a distraction with the help of a female swayamsevak from Maningar. They went to the police station where Deshmukh was being held. While she posed as a relative and contrived a meeting with the prisoner, Modi somehow took the documents from under the noses of the police.

Or:

Modi was also responsible for transportation and travel to Gujarat of those opponents of Indra still at liberty…Modi too, in the course of his duties, was compelled to travel, often with pamphlets that could have got him arrested. To minimize the risk he became a master of disguise, something that came naturally to one who always paid attention to his appearance. On one outing, he would appear as a saffron-robed sanyasi; on another, as a turbaned Sikh. One time he was sitting in a railway carriage, hiding behind a thick black beard, when his old schoolteacher sat down next to the grown-up “urchin”. The disguise worked perfectly, but some years afterwards the teacher attested that as Narendra disembarked, he introduced himself and offered a hearty saluation.

Still, the Emergency ground on. One aspect the book doesn’t stress, but which I was surprised to read about when Googling the period, was the forced sterilizations. Under pressure from the US and UN to control exponentially rising populations, Indira had started various population control efforts in the 60s, all ambiguously voluntary. Over time, the level of pressure ratcheted up, and during the Emergency the previously-ambiguous coercion became naked and violent. “In 1976-1977, the programme led to 8.3 million sterilisations, most of them forced”.

How did this end? Gandhi called an election - during which she was predictably voted out completely and her party lost more thoroughly than any party has ever lost anything before. Her opponents’ campaign was based on things like “she just forceably sterilized 8 million people and you could be next”, which is honestly a pretty compelling platform. The real question is why she gave up her emergency dictatorship and called an election at all. According to the book:

It is more likely that in ending the Emergency Indira was thinking of herself, not India. She was aware of her growing international reputation as a tyrant, the daughter of a great democratic leader whose legacy she had damaged. As the journalist Tavleen Singh points out, the pressure to end the Emergency came simply from Indira Gandhi finding it unbearable that ‘the Western media had taken to calling her a dictator.’

(but before you interpret this as too inspiring a story of the victory of good over evil, Indira Gandhi was voted back in as prime minister three years later. We’ll get to that.)

Modi came out of the Emergency a rising star, appreciated by all for his logistical role in the Resistance. In the newly open political climate, the RSS was devoting more attention to their political wing and asked Modi to come on as a sort of campaign-manager-at-large, who would travel all around India and help friendly politicians get elected. He turned out to be really good at this, and rose through the ranks until he was one of the leading lights of the new BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party, “Indian People’s Party”). He spent the next two decades running campaigns, traveling the country, and getting involved in internal backstabbing (which he had a habit of losing in ways that got him kicked out of the party just before something terrible happened, leaving him as the only person untarnished by the terrible thing when they inevitably invited him back). Finally some of Modi’s political enemies failed badly in the leadership of Gujarat - one was expelled for corruption, another suffered several natural disasters which he responded to poorly. Modi had been accepted back into the party. He was beloved by Gujaratis, who still remembered his heroic work during the Resistance. He was the only person untarnished by various terrible things. By the rules of Indian politics, it was the party’s choice who would replace the resigning incumbent as Chief Minister of Gujarat, and as Modi tells it, everyone else just kind of agreed he was the natural choice (his enemies say he did various scheming and backstabbing at this point). So on October 7 2001, Narendra Modi was sworn in as Chief Minister of Gujarat, India’s fifth-largest state.

IV.

The book pauses here to give us Narendra Modi’s view of Indian politics.

The Congress Party ruled India essentially as a socialist one-party state from its independence in 1947 to 1977, and then again with brief interruptions until 1996. To hear Modi tell it, they’re the essence of everything corrupt, cronyist, colonialist, dynastic, and dictatorial.

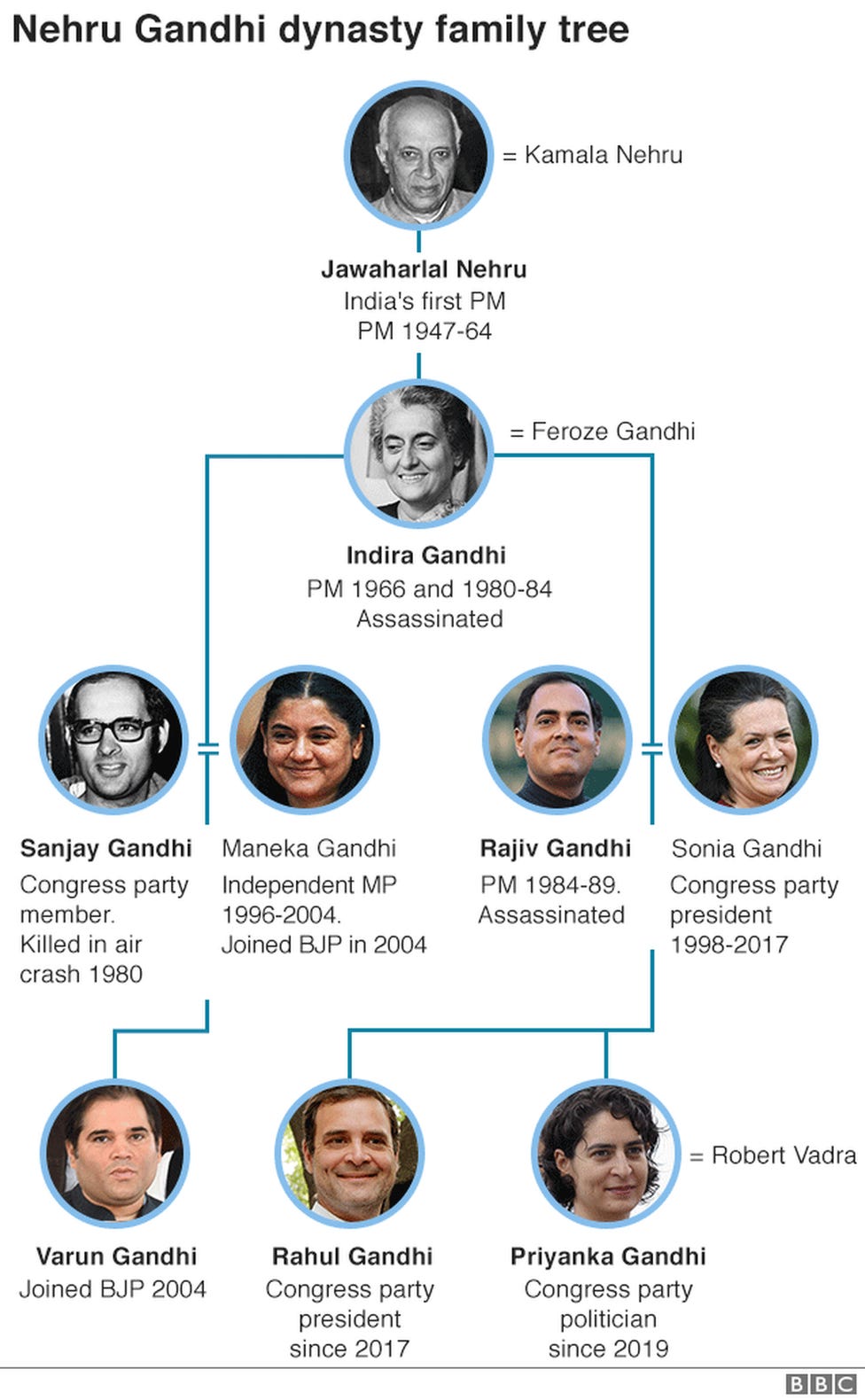

The dynastic part, at least, is hard to argue against. Until 1962, it was led by Indian founding father Jawaharlal Nehru. From then until 1984 it was led by his daughter, Indira Gandhi. From then until 1989 it was led by her son, Rajiv Gandhi. From 1999 to 2014 it was led by his (ethnically Italian) wife, Sonia Gandhi. And from 2014 to present, by Rajiv and Sonia’s son, Rahul Gandhi.

Source: BBC. I bet Varun has an interesting story.

Source: BBC. I bet Varun has an interesting story.

Modi accuses the Congress Party of being the descendants of those Indians who did well under British colonialism, liked British colonialism a little too much, and basically Europeanized - including a European-style semi-racist contempt for ordinary Indians. They’re the kind of people who would happily force-sterilize eight milion of their countrymen because Western powers called India “backwards” for having too high population growth. The sort of people who would declare an Emergency dictatorship, happily kill or imprison hundreds of thousands of Indians without moral compunction, then immediately back down when Western media said they looked bad. They dominate the media, academia, and NGOs (all of which Modi accuses of being sycophantic and complicit in Emergency atrocities and everything else bad that Congress has ever done, while coming up with ways to make the most neutral actions by Congress’ opponents look like dastardly acts of villainy). Their policies, insofar as they have any, involve whatever forms of socialism don’t really help the poor but do ensure that anything that anyone wants to do requires permission from elites first, eg the “License Raj”. According to Modi, the Congress Party hates the average Indian and the average Indian hates them right back. They survived as a democratic party by preventing any real opposition from forming, plus using their media connections to spread fear and division among people, plus occasionally just declaring martial law and imprisoning anyone they didn’t like.

But by 1980ish some opposition parties had managed to take hold, and Congress realized they would have to win semi-fair elections. Starting in 1980 - the year Indira Gandhi managed to get herself re-elected - they found a new strategy. They got the media to paint ordinary Indians as evil intolerant racists, then appealed to minority groups, saying they were the only people who could swoop in and save them from this violent hateful majority.

According to Modi, when he was growing up (the 1950s) there was little racial division. Hindus and Muslims lived together and socialized together; Modi’s own childhood best friend was a Muslim boy from a few blocks away. He attributes the worst prejudice and division in modern Indian society to the results of this Congress push to get everyone hating each other. Implausible? Kind of. But I remember reading Salman Rushdie, an Indian Muslim (though, uh, not a very good one), who also says there was almost no racial animus in his native Kashmir when he was growing up in the 1940s. And there’s a historical pattern where there’s decreased ethnic strife during colonial empires (since the colonizers are firmly in control, there’s not much to be won in competitions between colonized groups), and then worsening strife after decolonization (different ethnic groups fight for control, or demagogues try to win elections by fanning inter-ethnic hatred). So I am not going to reject it out of hand when Modi says things were better back in the past - though I’m also can’t ignore everyone else’s position that worsening relations are due to Modi and people like him.

Modi’s Exhibit A here is the Shah Bano case. A rich Muslim lawyer divorced his wife after forty years of marriage. She had no source of income and wanted alimony, as per Indian divorce law. Her husband said no, because Muslim divorce law didn’t require him to pay anything, and Indian law makes some concessions to Muslim custom. The Indian Supreme Court said huh, what are you talking about, you still have to follow the law regardless of your religion, and ordered him to pay up. Rajiv Gandhi and the Congress Party had just taken power on a pro-Muslim platform, and in order to placate their base they passed a law rescinding the Supreme Court judgment and saying Muslim men didn’t have to follow the rules around alimony if they didn’t want to.

This kind of thing is why Modi, despite everyone else calling him a Hindu fanatic, insists he is a defender of secularism. He thinks everyone else keeps trying to give special rights based on religion in order to court minority groups and win elections, and he is saying the normal reasonable secular thing of “there are just some nationwide laws, everybody has to follow them, f@#k you if you don’t want to”. His enemies might point out that those nationwide laws will be instituted by a majority-Hindu populace; he accepts that, but doesn’t care. You can’t have a modern liberal democracy while constantly giving out special rights to any group you need votes from in this year’s election.

But it’s not just Muslims. In one incident, he has to defuse anger over Congress’ plan to give extra seats at colleges to Adivasis, a group translated into English as “forest-dwellers”; in another, Congress courts the Kshatriyas, “a warrior caste which felt its historical glories were insufficiently supported by its status in modern society”. At least US identity politics have the common courtesy to sort everyone by skin color. The Indian version combines all the fun of racial sensitivity training with all the simplicity of one of those D&D expansions that have a bunch of species with names like “Aarakocra” or “Tabaxi” for the special snowflakes too cool to be elves or halflings. As Modi tells it, Congress tries to peel each of these groups off from the majority by promising them special rights and affirmative action, with disastrous results:

Another commission for improving the lot of sixty-three minorities and backward classes…was formed on 20 April 1982…fourteen months later, Solanki decided to implement its recommendation of an extra 18% reservations, bringing the total quota to 49%. This was inacted immediately prior to the March 1985 Gujarat assembly elections, cynically timed to boost the [minority] vote. Solanki reversed the commission’s stress on the definition of [backward castes] by income and instead insisted on caste, ignoring its cut-off limit of an income of 10,000 rupees, probably to lure the relatively prosperous Kshatriyas. The result again was statewide rioting […]

In the ensuing riots, which began in February 1985 during the assembly election campaign, the anger of the mobs was underlined by the shock that reservations were cumulative, so that if quotas were not filled in one year, they ‘rolled over’ to the next, adding to the reservations all the way to a possible 100%. ‘The thought that they could be effectively barred from all seats of learning was enough for upper-caste people to go berserk’, wrote one author. The army was called in, and the prime minister and the Union home minister had to visit Ahmedabad to try and calm the situation. Nevertheless, 23 houses were burnt to ashes in the Dabgarwad neighborhood and 180 people died while 6000 were left homeless.

But backward castes were becoming convinced that Congress was on their side, and the effect was social polarization. As there was a majority of lower-caste voters, this suited the Congress perfectly.

Modi describes spending his years of campaign consultancy trying to figure out a way around this dynamic. You could support more and more affirmative action, stoke more and more community tensions, and get those delicious minority votes while making the majority hate you - or you could roll back affirmative action, doom backward castes and Muslims to irrelevancy, get tarred as a racist, and ruin your electoral chances.

The solution he finally settled on was free market capitalism. As he tells it, as long as the pie is a fixed size, everyone will always fight viciously over their share. If you can get the pie growing, people will calm down and focus on making money. Over the preceding fifty years of Congress-led socialism and the “License Raj”, India’s GDP had grown at a pathetic 3% / year, which snarky observers called “the Hindu rate of growth”. If he could get the market moving again, maybe he could turn India into a genuinely secular state where people had aspirations beyond getting a few more of those sweet affirmative action slots for your own group.

V.

Four months after Modi became chief minister of Gujarat, there was a terrible riot. Muslims set a train car full of Hindu pilgrims on fire, and mobs of vengeful Hindus went around murdering Muslims for days, with further outbreaks continuing for weeks. By the time everything was done, 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus had died.

Everyone else thinks Modi either caused the riot, encouraged it, and/or at least deliberately avoided sending in enough police to stop it effectively. Modi vociferously denies all of this. He said he did everything he could to stop it but it didn’t work. He said that if he is guilty of contributing to or failing to ameliorate the riots in any way, he “should be hanged”. He has refused multiple demands to apologize because:

This blot happened during my tenure and I have to wash it off. People told us Modi never says sorry. I said, what does sorry mean. We have a criminal justice system in this country which does not accept sorry. What will Narendra Modi’s sorry mean to us? We will judge his sorry from his actual doing.

The book, to its credit, doesn’t in any way gloss over the riots. It spends about 50 pages - a fifth of the whole text - presenting Modi’s case for why he is blameless. I don’t want to repeat it here, because (although he presents his case well) I think there’s a pretty good chance he’s lying. I don’t want to reprint an apology (or more accurately non-apology) for genocide without fact-checking it, and the complexity of the issue is such that it would take forever to fact-check to an acceptable standard. Here’s an article you can read for the full anti-Modi case, and you can get this book for the pro-Modi one. At some point I may actually go through this with the thoroughness it deserves. For now, I’ll just present these facts:

- Modi completely denies responsibility.

- Journalists, NGOs, and foreign experts mostly say Modi is at fault, to the point where the US and various European countries have denied him visas.

- The Indian Supreme Court found him innocent of the specific charges they were reviewing, but the decision was controversial.

Modi claims that after this disaster, he tried to resign a few times and his party wouldn’t let him. After that, he decided to dissolve the government and hold new elections, to “let the voters decide my future”. Modi won the ensuing election in the biggest landslide in Gujarati history, getting 126 seats to Congress’s 51. Why?

The December 2002 Gujarat state elction was described as ‘driven by hatred of Hindus towards Muslims’. More likely it was driven by the media’s dislike of Modi and in turn the Gujaratis’ dislike of the media. ‘Little did they [the media] ralise they were creating a constituency that would later buy into the logic of the Gaurav Yatra that Mr. Narendra Modi so successfully enlisted in the cause of route-mapping his election campaign,’ wrote Debraj Mookerjee in his coruscating post-election condemnation of ‘pseudo-secularists’. They failed to understand that ‘the triumphal march posited Hindu pride only in the derivative. What really was being rallied to a pitch was Gujarati pride.

The net effect of the general hostility directed at Gujarat and its chief minister was to precipitate a voting landslide for the BJP… Dasgupta summed up Modi’s triumph concisely: ‘He successfully established a direct correlation between demonology and adulation: the more he became a hate figure in cosmopolitan circles, the more his popularity soared in Gujarat…this was only incidentally an election centred on ideology; the real issue was leadership.”

For all the fiery speech-making, the election campaign had not been about Hindutva or even about terrorism. Thanks largely to the media, it had been about Modi. With hindsight, Sonia [Gandhi, leader of the Congress Party] had accurately recognized the long-term threat Modi’s politics posed to the Congress. Over ten years later, with a barely reduced majority in the Gujarat assembly, Modi was elected for the third time. Few Muslims had voted for him in December 2002. But in December 2012, 31% did…Would the Congress belatedly realize that its tactics had backfired and that for every insult it aimed at Modi it handed him another thousand votes? Or would it double down on its losses and bet more heavily on demonizing him? Time his proved that it would choose to do the latter, with interesting consequences.

In other words, he says the media’s attacks on him after the riots were so vicious and baseless that they made ordinary Gujaratis, who didn’t like or trust the media, think he was on their side. The part about yatras refers to giant parades that Modi held during his campaign. The media played these up as scary fascist rallies, but as per Modi everyone had a good time and celebrated their shared Gujarati pride. When the papers kept saying that having Gujarati pride was equivalent to being a violent terrorist, all the proud Gujaratis who liked the parades realized the media wasn’t on their side, and voted for him out of spite.

There follow approximately ten years of Modi being a popular and constantly-reelected Chief Minister of Gujarat. The general pattern (as per his description) goes: Modi makes some common-sense reform. The media plasters India with claims that it is a violent attempt to oppress minorities. The reform goes fine, everyone including minorities benefits, and Modi’s star rises further. Here’s a typical page:

The New York Times quoted figures issued by the National Sample Survey Office [that] showed poverty levels for Muslims in Gujarat at 39.4% in 1999-2000 and still 37.6% in 2009-2010…for Gujarat’s Muslims not to have improved their fortunes at all - to have experienced by comparison a catastrophic decline as overall poverty in Gujarat fell by 47.8%…was surely a searing indictment of Modi’s policies.

In fact, the NSSO had already released a newer set of data for 2011-2012 that showed the number of Gujarati Muslims below the official poverty line at only 11.4% compared with a national average of 25.5%. This was the fifth best performance by a state in India…this proved exactly the opposite of the point made by the New York Times…so why had nobody else noticed, and why was the 2009-2010 figure being taken at face value? […]

The resistance against accepting evidence of progress under Modi’s regime, especially progress among Muslims, appears to be linked not to conspiracy so much as to an ingrained impression left in the public mind about the 2002 riots. Many people simply refuse to believe that Modi is capable of benign behavior, especially towards Muslims, and are therefore disinclined to believe good news.

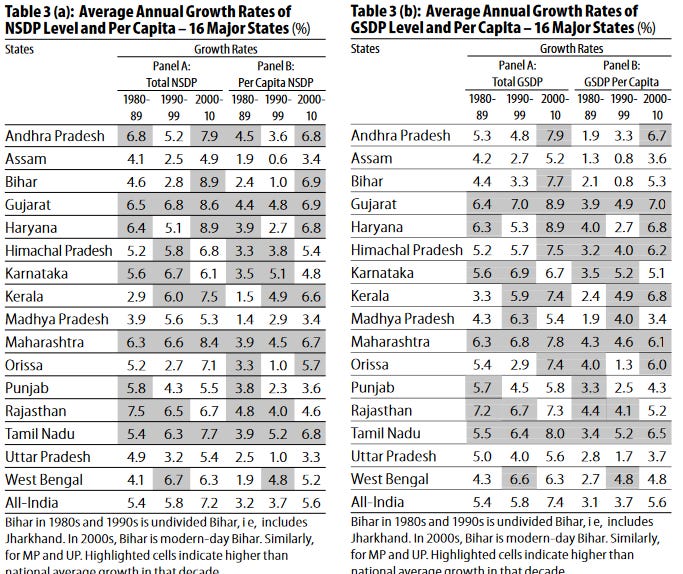

The book spends a long time rebutting claims that Modi’s tenure in Gujarat wasn’t an amazing economic success story. This one I did look up, and as usual the story is complicated. Going by the raw-est of raw numbers, Modi looks very good here:

Source is here. Gujarat does pretty well even pre-Modi (1990-2000), but during Modi’s administration (2000 - 2010) it does really well.

Source is here. Gujarat does pretty well even pre-Modi (1990-2000), but during Modi’s administration (2000 - 2010) it does really well.

Zoom in a little and you can make a case that the success was more measured ; on a lot of metrics, it’s Kerala and not Gujarat that was the real positive outlier. I think this is because Gujarat pursued more free-market policies, Kerala pursued more socialist policies, and both did well by their own standards. If you look at size of the economy, Gujarat does slightly better; if you look at measures of equality or poor people’s ability to access services, Kerala does. Either way, I think the clearest conclusion is that Modi’s administration was pretty successful but didn’t blow everyone else out of the water or anything.

So how did Modi become famous enough to use the position as a springboard to national power? For one thing, he was genuine in his commitment to cut red tape and unwind India’s socialist legacy, which made him seem like the only person with a real alternative to the status quo. For another (his preferred explanation), the constant nationwide media attacks on him kept his name in the news: it felt like the elites were saying he was the guy they were afraid of, and everyone who wanted a guy the elites were afraid of was all too happy to take them at their word. For another (Modi self-servingly claims), the media’s constant attempts to tar him as far-right gave him a mandate to actually be pretty moderate and (when needed) pro-Muslim, in the “only Nixon can go to China” sense. Finally, he had a reputation as the least corrupt person in Indian government - something his biography, religious views, and sense of personal austerity helped back up. His time in Gujarat was mostly unmarked by corruption scandals, and he made the right noises about fighting corruption in his underlings. This was a special draw after an especially corrupt Congress administration.

Also, Modi had spent most of his career as a campaign manager and was widely considered the best one in India, which probably didn’t hurt his own efforts. He was elected Prime Minister with, as usual, a landslide majority - at which point the book ends.

VI.

As an entry in the Dictator Book Club, this book leaves a lot to be desired. For one thing, it ends before Modi gets enough national power to really start threatening democratic institutions. For another, even if he did start threatening democratic institutions, I wouldn’t trust Andy Marino to tell me about it. I hope to find a more complete and balanced biography later. In the meantime, what can we conclude?

Modi’s rise eerily parallels Erdogan’s. Both grew up in poor families and got involved early in religious/political organizations. Both were sufficiently committed to their religious/political organization that they joined as junior cadets even though religious parties had never taken power in their country and it seemed like career suicide. Both suffered through genuinely-terrible dictatorships led by secular liberal elites, which soured them on a secular liberal model. Both rose through the ranks of their parties and got elected regional administrators. Both did good jobs as administrators, plus had the PR skills to make it look like they did even better jobs than they did. Both used their religious connections to semi-accurately present themselves as beacons of piety and virtue amid a corrupt establishment. Both tried to shed their party’s far-right image in favor of being center-right free market capitalists, and both implemented free-market reforms that helped them get the credit for a good economy. Both were raised to power by a coalition of moderate-rightists who wanted good economic policy and were wowed by their administrative accomplishments, plus far-right religious zealots who expected that it was all a charade and they would govern as far-right religious zealots.

Both are much more similar to each other than either to Trump. Nobody thought Trump was honestly religious, and nobody thought he was a beacon of ascetism and non-corruption. I was going to add that Trump never had any history as a competent regional administrator, but I guess people who believed his reality show persona believed he was an unusually skilled businessman, which maybe ticks that box. He didn’t shed a far-right image to appeal to center-right capitalists - he kind of did the reverse - but maybe the fundamental nature of the Republican Party did that balancing act for him.

I was struck by Modi’s view of Indian politics: educated elites cynically fanning racial discord so they could force minority groups to flee to them as “protectors”. This is probably how Trump would describe the Democrats if he was smart enough to think of it. Of course, Modi’s enemies turned it around and called Modi a populist-nationalist leader keeping a veneer of plausible deniability while inciting anger/suspicion/violence against minority groups, which is of course how the Democrats think of the Trump-era Republicans. All the most recent trends in American politics happened in India too, only ten years earlier.

(questions about minorities and racism were less prominent in Erdogan’s rise, making him a proof of concept that you can do this without them)

For me the most interesting Modi/Trump parallel was the former’s insistence that Gujaratis loved him because they hated the media who hated him. On the one hand, this is a convenient self-serving thing for him to say, because the leading alternative explanation is that they loved him because he was a violent racist and they were pro-violent-racism. On the other, it’s hard not to remember the 2016 primary, when this was one of the leading explanations for how Trump suddenly rose to the front of the pack: the media hated him so much that they couldn’t stop giving him free airtime.

In my review of Art Of The Deal , I quoted Donald Trump’s advice on dealing with reporters:

One thing I’ve learned about the press is that they’re always hungry for a good story, and the more sensational the better. It’s in the nature of the job, and I understand that. The point is that if you are a little different, or a little outrageous, or if you do things that are bold or controversial, the press is going to write about you. The funny thing is that even a critical story, which may be hurtful personally, can be very valuable to your business. [When I announced my plans to build a huge new real estate development to the press], not all of them liked the idea of the world’s tallest building. But the point is that we got a lot of attention, and that alone creates value.

Now Narendra Modi says the same thing - he thinks that the negative press he got from being outrageous paved his road to power. When all these demagogues who succeeded against all odds tell you what strategy they used, maybe you should believe them.

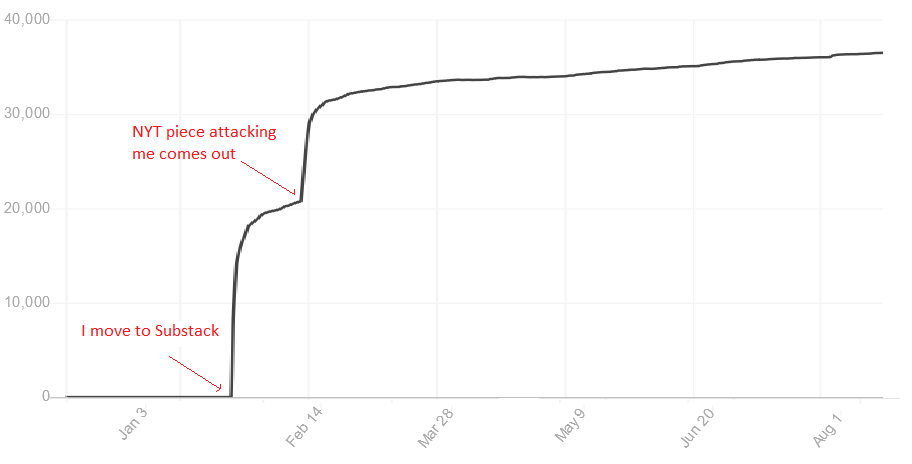

I’m not a far-right demagogue and I don’t want to be a head of government. But I did manage to piss off the New York Times last year, and they wrote a retaliatory hit piece against me. It accused me of being racist, sexist, elitist, all kinds of negative things. There was nothing about it that even hinted I was an acceptable person in any way. Here’s what happened to my email subscriber numbers after the piece was published:

It took me eight years of blogging to get those first 20,000 readers. The NYT hit piece gave me another 11,000 in a day. Many of them stuck around; some bought subscriptions. At meetups, many fans tell me the hit piece first brought them to the blog. I didn’t intend this, and I don’t consider it fair compensation for the level of reputational damage they did me.

But if I ever want to become Prime Minister of India, I know what strategy I’m going to use.