Book Review: Rhythms Of The Brain

Brain waves have always felt like a mystery. You learn some psychology, some neuroscience, a bit of neuroanatomy. And then totally separate from all of this, you know that there are things called “brain waves” that get measured with an EEG. Why should the brain have waves? Are they involved in thinking or feeling or something? How do you do computation when your processors are firing in a rhythmic pattern dozens of times per second? Why don’t AIs have anything like brain waves? Should they?

I read Rhythms Of The Brain by Prof. Gyorgy Buzsaki to answer these questions. This is a tough book, probably more aimed at neuroscientists than laypeople, and I don’t claim to have gotten more than the most superficial understanding of it. But as far as I know it’s the only book on brain waves - and so our only option for solving the mystery. This review is my weak and confused attempt to transmit it, which I hope will encourage other people toward more successful efforts.

Why Brain Waves?

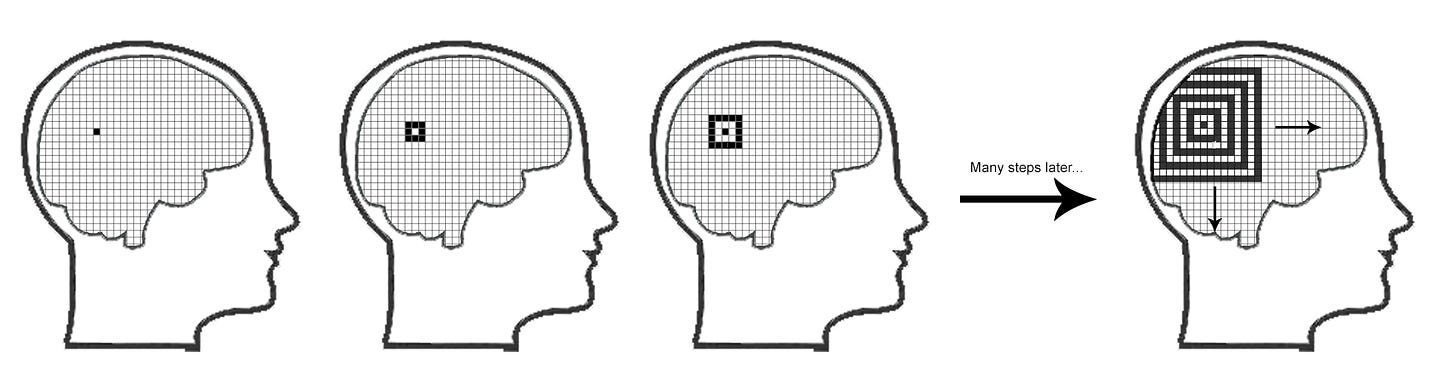

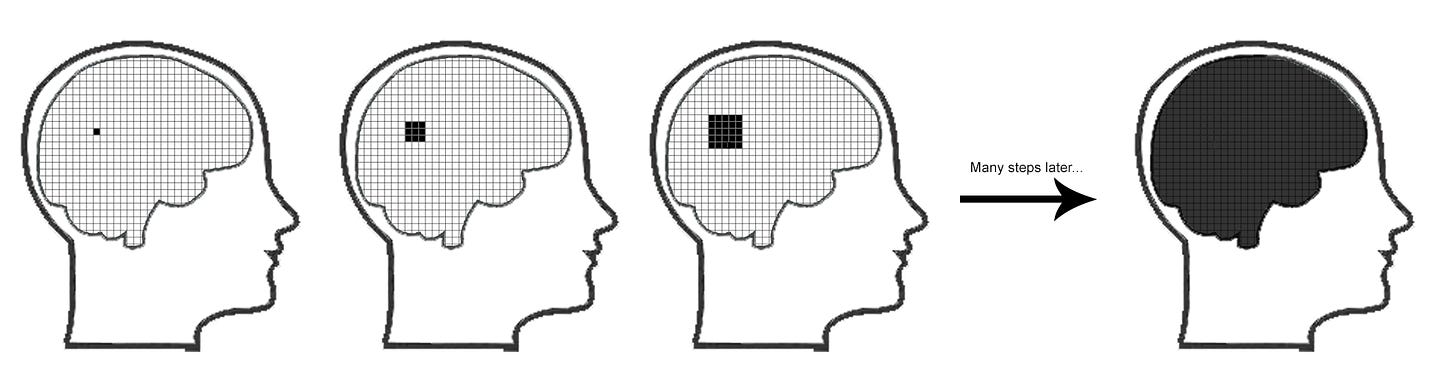

Here’s an oversimplified fake answer: imagine a completely silent brain, with all neurons connected to nearby neurons, and whenever a neuron fires it makes its neighbors fire. Some external stimulus (let’s say a flash of light) makes one neuron (let’s say in the visual cortex) fire. What happens?

I can’t stress enough how fake this is.

I can’t stress enough how fake this is.

The single neuron fires, it makes its neighbors fire, they make their neighbors fire, and you get a spreading wave of activation across the whole brain.

One way this model is fake and bad: it assumes neurons are either in a steady “off” or “on” state, and that once “on”, they stay “on” forever. Here’s a very slightly less fake model: a neuron goes “on” for one tick of the clock, then switches to “off” for one tick (refractory period), then is available to be switched “on” again. What happens now?

You get concentric rings of oscillating on and off!

I can’t stress enough how fake this model is. Buzsaki doesn’t use it; even his simplified examples are much more careful. But this was what helped me (a person who is not a neuroscientist but does play around with Conway’s Game of Life sometimes) get a basic intuition of why the brain might produce oscillations.

Here are five of the most important differences between this fake model and a real brain:

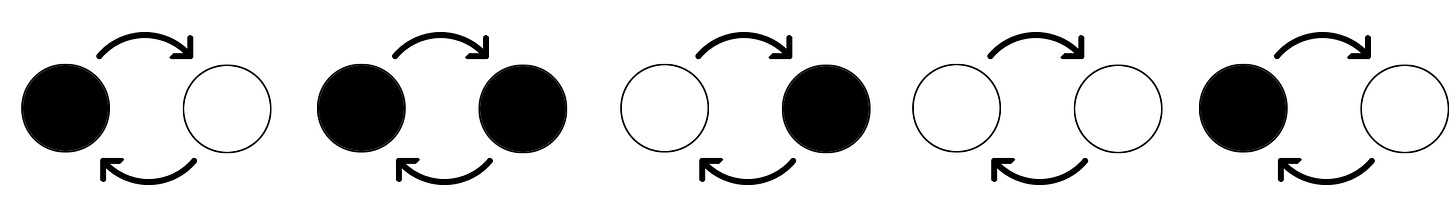

1: The real brain has more sources of oscillations. For example, many are produced by inhibitory interneurons - neurons that, when turned “on”, turn other neurons off:

A normal excitatory neuron is linked to an inhibitory neuron. Whenever the excitatory neuron fires, it makes the inhibitory neuron fire; whenever the inhibitor neuron fires, it turns off the excitatory neuron. Once the excitatory neuron is off, that turns off the inhibitory neuron, leaving the excitatory neuron free to fire again if the original stimulus is still there.

2: Also, sometimes individual neurons oscillate on their own. Whenever they get too depolarized, that opens ion channels that repolarize them again, and vice versa. If you take a neuron out of the brain and put it in a test tube, it might fire at some natural frequency not necessarily related to its frequency in the broader network of the brain; it contributes its own frequency, which other nearby cells speed up or slow down.

3: In the fake model, every neuron was connected to a few nearby neighbors. The real brain has a much more complicated graph. Neurons can connect to thousands of other neurons, and one out of every X connections goes somewhere far away on the other side of the brain, for the same reason a good transportation network has some local trains vs. some express trains - you can get from Point A to Point B fastest with a combination of fast direct long-range connections and slower short-range ones.

4: The real brain includes many different kinds of neurons, inhibitory neurons, connections between neurons, and types of tissues with different graph theoretic organizations. If the fake model is kind of like the Game of Life, the real model is kind of like a version of the Game of Life in some contorted multidimensional space with each cell following a different rule set.

5: Also there is actual sensory stimulation and cognition happening in lots of places at once, messing up the otherwise elegant wave pattern.

So instead of one oscillation taking over the whole brain, you get lots of oscillations with different properties arising, competing against, and interfering with each other, producing complicated self-organizing patterns that arise and disappear from moment to moment

Complex patterns arising and evolving in the Game of Life.

Complex patterns arising and evolving in the Game of Life.

What Are Brain Waves Like?

In the real brain, with many areas and types of neurons and sources of stimulation, the many different oscillations settle into what Buzsaki calls a 1/n, scale-free, or pink noise pattern.

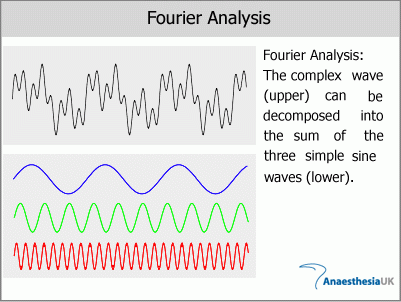

Complex waves can be decomposed by Fourier analysis into sums of simpler regular waves:

(source)

(source)

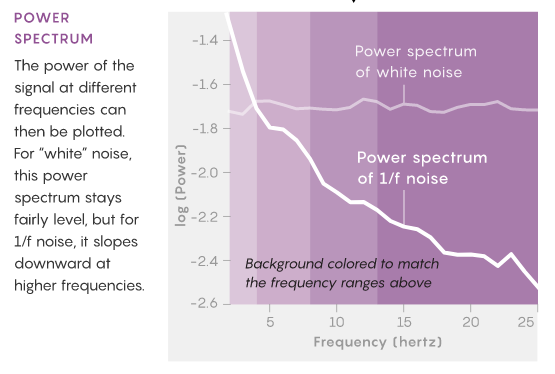

If you measure “brain waves” with an EEG, you get some very complex summed total wave. When you break it down, you find that as frequency goes up, power goes down, according to a power law. In the study of sound, this pattern is called “pink noise”.

(source)

(source)

Pink noise is apparently omnipresent in natural systems for kind of mysterious reasons - see eg this Quanta article, which says pink noise “is found in all kinds of electrical noise, stock market activity, biological rhythms, and even pieces of music — and no one [knows] why.” Buzsaki is pretty excited about this, and suggests that human-produced music has a pink noise spectrum in order to complement the pink noise spectrum of the brain; other sources argue that literal pink noise (for example, from a fan) has healing properties compared to white noise or silence.

Did you know: White noise was named because its wave spectrum resembles white light. Pink noise was named because its wave spectrum resembles pink light. Brown noise was named after Robert Brown, who helped discover it. This is one of my least favorite facts.

Did you know: White noise was named because its wave spectrum resembles white light. Pink noise was named because its wave spectrum resembles pink light. Brown noise was named after Robert Brown, who helped discover it. This is one of my least favorite facts.

Lots of scientists seem tempted to wax rhapsodic about the importance of pink noise; the exact reasons were one of the parts of the book I didn’t quite understand. For our purposes, it just matters that this is the overall wave spectrum of the brain.

How is this spectrum formed? This was one of the questions the book didn’t resolve for me. Are there a few hundred neurons here oscillating at 1 hertz, a few thousand there oscillating at 1.1 hertz, and so on, until we have enumerated thousands of different neuronal populations with very slightly different rhythms, and when you add them together you get the nice smooth pink noise curve? And then after a second, they all spontaneously rearrange themselves and there are a different few thousand populations and rhythms, still on the aggregate summing to pink noise? Sometimes it seems like the book is pointing to a model like this.

Other times it seems like there are approximately five different rhythms in the brain, each with a name like “hippocampal theta” or “visual alpha”, and each usually involving a whole brain macroregion (eg the visual cortex). I still haven’t figured out how to reconcile these two perspectives - maybe the major rhythms are broad categories, and there are lots of subrhythms within them?

In any case, these 1/n rhythms form the “background noise” of the brain. They exist at all times, whether you’re thinking hard, or in a sensory deprivation tank, or asleep (although each of those states will change which rhythm predominates). When neuroscientists want to study how the brain reacts to something, they usually measure the brain, do the thing, and subtract the pink noise spectrum from the result - again, on the grounds that it’s “background noise” which is disguising the effect of whatever their interesting intervention was. Buzsaki questions this practice and presents evidence that the state of the “background noise” matters a lot - this is the “randomness” that explains why the same person will respond to the same intervention different ways at different times. For example, he presents evidence showing that if you give someone a near-threshold stimulus (for example, a flashing light just barely bright enough that someone can detect it 50% of the time), then whether they detect it or not will depend on whether it occurs at the peak or the trough of the brain waves in the relevant area.

Are Brain Waves Useful?

Brain waves are kind of unavoidable. Rhythms presents a thought experiment about trying to design a brain that doesn’t fall into any natural oscillatory patterns. It’s pretty hard! Even if brain waves were useless, we would probably have them just because they’re too much trouble to avoid.

Still, evolution tends to make virtues out of necessity, and Buzsaki thinks brain waves matter a lot. Again without claiming to have fully understood this, here are four things that brain waves might do:

-

Brain waves provide “synchrony”, allowing a smallest granular unit of time and essentially converting life into a turn-based game. Suppose that a snake bites your foot. You see the snake with your eyes, and also get a pain signal from your foot. The pain signal has to travel a long way, nerves have conduction delays, and so it reaches your brain well after the visual signal. But your brain needs to be able to combine the visual and pain signals into a single story (snake bit my foot). Brain waves separate experience into short granular “turns” so that the brain can attribute both stimuli to the same “turn” and connect them. It’s also possible I’m totally misunderstanding this part, sorry.

-

Brain waves let neurons “join together” into a single unit. Neuroscientists sometimes talk about “grandmother cells” - that is, what neural events correlate to you thinking about your grandmother (or recognizing your grandmother when you see her)? One theory, somewhat supported by the data, is that there is a single specific cell representing her, and when that cell fires, you are “thinking about your grandmother”. Buzsaki thinks this is some, but not all, of the story. The rest of the story involves various cells involved in various grandmother-related tasks (visual cells representing your image of your grandmother, auditory cells representing her voice, associative cells representing memories about her) all joining together in a single oscillation (maybe they’re all firing simultaneously at 100 hertz, while all the non-grandmother-related cells around them are firing at some other rhythm). This “links” the cells into a single concept - your grandmother - that can then do other things or be used for computational work.

-

Similarly, brain waves determine (or reflect?) which structures are “talking” to which other structures. The hippocampus, a structure involved in memory, has its own rhythm called hippocampal theta. When some part of your auditory cortex is trying to remember something, it goes into hippocampal theta, “links up with” the hippocampus, and for a while that part of the cortex and the hippocampus effectively form a single fluid computational unit. Then when it’s done, it goes back into its normal rhythm and separates from the hippocampus again. The progress of waves might even reflect causal priority; when a cat is using sight to navigate and smell to confirm, waves progress from a visual region to an olfactory region; when the cat switches to using the smell to navigate and vision to confirm, the waves reverse direction.

-

Brain waves help keep the brain “critical”, ie close to “phase transitions”, ie interesting. If the brain were so undersensitive that almost nothing could make neurons fire, we wouldn’t be sensing or doing much. If it were so hypersensitive that the slightest touch provoked an unstoppable wave of spreading activation, we would have seizures all the time. Instead, the brain maintains a balance on many different scales - the scale of individual neurons, the scale of neuronal assemblies, etc - where it might do something but also might not. Brain waves control potential sensitivity by funneling it into stable oscillations instead of unstable vicious cycles. One example from the book: suppose there is a frequently repeating stimulus (eg a dripping sink). And suppose you will only detect the stimulus if it hits a neuron right on the edge of firing (eg if its electrical potential is between -60 and -59 mV). Since a neuron in a brain wave is oscillating among all possible values, at some point the stimulus will hit when the value is correct, and the neuron will fire (slightly earlier than it would have otherwise).

See also Oscillatory Synchrony Is Energetically Cheap.

What Kinds Of Brain Waves Are There?

This is the classic Greek letter system presented in any Neuroscience 101 class:

(source)

(source)

Alpha has traditionally been considered the rhythm of the “idling” brain, with some justification. For example, when you close your eyes, the visual cortex goes into alpha rhythm; when you meditate, alpha power in the brain goes up. Buzsaki presents various pieces of evidence showing that this isn’t the whole story and that alpha is involved in cognition - but it’s enough of the story for our purposes.

Theta is most important in the hippocampus. The hippocampus is traditionally associated with memory, but Buzsaki cites recent research showing that it also handles navigation (eg a rat navigating a maze, or a person walking through a familiar city). Why this combination of tasks? Rhythms sort of suggests that brain areas are less about specific tasks than about specific graph-theoretic arrangements, which are convenient for specific algorithms, which are convenient for specific tasks. The neural connections in the hippocampus are mostly local in a way that makes it a good “auto-associater”, ie you give it part of a pattern and it can recognize which pattern is being suggested. For complicated reasons this works well for both spatial tasks and memory. In fact, Buzsaki sketches out a way that episodic memory might have evolved from our navigation system, where eg remembering a list is equivalent to remembering a path through space, and remembering a specific episode is equivalent to remembering a landmark (he doesn’t specifically say so, but this is a fascinating match for the method of loci mnemonic device). Theta rhythm is an oscillation that helps divide navigation into time steps so you can figure out where you are now, where you were a moment ago, and where you’re going.

Gamma was the rhythm I found most interesting - it seems to map very well to “items in conscious awareness”. Ask someone to think about a certain topic, and cells representing that topic will form a neuronal assembly (ie they will start oscillating together at the same frequency) in gamma rhythm. I was pretty surprised that there was this clear of a neural correlate of consciousness.

In one particularly fascinating section, Buzsaki notes that the frequency of gamma waves is about 7x the frequency of theta waves. He shows how this means that the hippocampus (a sort of master regulator of short-term memory) can “call” conscious attention “as a function” seven times within one of its time steps, which he links to the old adage that you can fit seven plus or minus two items within short-term memory.

Along with these classic ones, Rhythms briefly touches on much faster or slower brain waves. Circadian rhythm can sort of be conceptualized as a brain oscillation lasting twenty-four hours, and there are other even longer-period brain oscillations of unclear purpose.

Okay, But Why Is This Interesting?

Rhythms Of The Brain is a very typical neuroscience book, which means it goes for phrases like “the grundicular region modulates output from the parashmoxular cortex” with the same fervor that the Bible hangs on “….and then Zebulav begat Ramulot.” There were a few hits of high-grade refined insight in it, but you had to look pretty hard to find them.

I read it anyway because of a talk with Andres of Qualia Research that convinced me that brain waves are potentially fascinating. Let me try to explain this, while admitting that unlike the work of the sober Professor Buzsaki, this is all total wild speculation that I can’t back up at all.

Advanced meditators say that at a certain level of concentration, time turns granular. Here’s Buddhist meditation teacher Culudasa:

If we observed closely enough, we would find that experience is actually divided into individual moments of consciousness. These conscious “mind moments” occur one at a time, in much the same way that a motion picture film is actually divided into separate frames…[This] basic premise of distinct moments of consciousness arising and passing away in sequence is based on the actual meditation experiences of advanced practitioners from across a broad range of traditions.

This matches Buzsaki’s description of brain waves as dividing conscious cognition into a series of time steps. It also matches the typical New Ager experience of “vibrations” or “vibes” in sufficiently altered states.

In my post on enlightenment experiences, I wrote that the explanation I found most plausible was “information processing in the brain switching to some new attractor state if you force it hard enough.” We can flesh this out more: what does this switch to a new attractor state look like? Well, it seems to happen in a flash - the typical description of satori is that one day you’re meditating, or walking through the forest, or whatever, and you suddenly just realize that all is one, or that suffering is illusory, or whatever it is that you realize. It seems to be a state that you can drift into and out of, it has something to do with the vibrations, and it involves redrawing the boundaries between self and other.

Andres suggests all of this is a good match for oscillatory coupling between brain regions, which he says “dissolves internal boundaries”. To give a fake toy example: suppose that you have some brain region representing the normal conscious self (maybe the default mode network), and some other brain region representing some part of the unconscious. When we say that these are “different brain regions”, we don’t just mean anatomically, we mean that they’re oscillating at different frequencies in a way that makes them less than fully communicative with each other. If two brain regions are oscillating at almost the same frequency, they will tend to link together - that is, if one area is 1.9 hertz, and another area is 2 hertz, then probably the 1.9 hertz area firing will trigger neurons in the 2 hertz area to fire (since they are almost ready to fire anyway), and the 2 hertz area will decrease to 1.9 hertz and the two areas will “merge” into a single 1.9 hertz rhythm. And if two brain regions are oscillating at frequencies that are near-multiples of each other (for example, 2 hertz and 4.1 hertz), then something similar will happen, with the 2 hertz region triggering the 4.1 hertz region every second peak, and eventually they will settle into an entrained 2 hertz vs. 4 hertz oscillation with the same peaks. Buzsaki says that in the brain you tend to see only surviving rhythms that are irregular multiples of each other (he says “the natural logarithm 2.17” - I don’t know if this is a typo for e = 2.72 or if something else is going on).

Suppose that - and again, this is a fake toy example - your unconscious is oscillating at 1 hertz and your default mode network is oscillating at 2.17 hertz. Then you meditate, you slow your default mode network to 2 hertz, all of a sudden consciousness and unconsciousness are nice multiples of each other, they reach oscillatory synchrony, and they achieve higher levels of communication with each other.

Andres thinks this is part of what’s behind “spiritual” or “mystical” experiences, where you suddenly feel like you’ve lost the boundaries of yourself and are at one with God and Nature and Everything. You’ve done something weird that’s slowed or sped up an oscillator somewhere, and it’s achieved synchrony with another oscillator it doesn’t usually communicate with.

(so is this enlightenment, full stop? I think that’s much more complicated and involves retraining various oscillators and building informational “connections” throughout the brain, such that everything is naturally trained to a common rhythm instead of relying on local pacemakers)

This would also provide an explanation for drug trips where people lose their sense of self in a more negative way. There is some oscillatory region (again, the default mode network would be a good guess) that usually communicates coherently. If you screw up all of your local pacemakers and connections that usually maintain that rhythm, all those parts of the brain will get on their own separate rhythms, not really communicate with each other, and you will lose the sense of yourself as a coherent entity. If you’ve ever had this happen to you, this story might sound frighteningly familiar.

All of this hints at some deep connection between brain waves, consciousness, and selfhood. Buzsaki also suspects something like this, although he is more circumspect, sticks closer to the evidence, and takes it in a somewhat different direction. The last section of Rhythms is called “Only Structures That Display Persistent Neuronal Activity And Involve Large Neuron Pools Support Consciousness”, and argues that:

Large numbers of neurons with small-world-like connectivity can give rise to regenerative, spontaneous activity of the 1/f type, [and] this self-organized activity is a potential source of consciousness . . . the cerebral cortex, with its self-organized, persistent oscillations and global computational principles, can create qualities fundamentally different from those provided by input-dependent local processing. It may turn out that the rhythms of the brain are also the rhythms of the mind.

One interesting place you could take this: are AIs conscious?

As far as I know, no AI uses anything like brain waves. This is for good reason. Brain waves exist partly because of the limits of wetware - neurons are noisy, and making them oscillate is a more elegant solution to the noise than letting them have seizures or whatever they would do on their own. And the waves solve wetware-specific problems, like conduction delay (silicon chips operate at the speed of light) and synchronization (computers have internal clocks, or can synchronize with atomic clocks via the Internet). So one possibility is that AIs don’t have brain waves because they don’t need them.

If brain waves are really responsible for things like attention and cross-talk between brain regions, then might a lack of brain-wave-equivalents make AIs worse at these things? Maybe, but maybe there will be computer-specific solutions to these problems much more elegant than the hackish oscillatory solutions evolution dreamed up for us.

But if brain waves are involved in selfhood, consciousness, and enlightenment, then would an AI that found some other route around this problem miss out on these things? Would this matter? Would it be a loss?

Rhythms Of The Brain will not answer these questions, but right now it’s the only starting point for anyone who wants to learn about brain oscillations. Read it, then explain to me what I missed.