Book Review: The Geography Of Madness

I.

Around the wide world, all cultures share a few key features. Anthropologists debate the precise extent, but the basics are always there. Language. Tools. Marriage. Family. Ritual. Music. And penis-stealing witches.

Nobody knows when the penis-stealing witches began their malign activities. Babylonian texts include sa-zi-ga, incantations against witchcraft-induced impotence. Ancient Chinese sources describe suo yang, the penis retracting into the body because of yin/yang imbalances. But the first crystal-clear reference was the Malleus Maleficarum , the 15th-century European witch-hunters’ manual. It included several chapters on how witches cast curses that apparently (though not actually) remove men’s penises.

This image (source) of a witch stealing a man’s penis, with a box of previously-stolen penises to her right accompanies the 1411 poem “Flowers Of Virtue” in its 1486 edition. Malleus Maleficarum was published in 1486, so if the original text of Flowers Of Virtue contained the incident this picture refers to, it would predate Malleus. But the original text is written in poetic medieval German and I can’t find a good translation.

This image (source) of a witch stealing a man’s penis, with a box of previously-stolen penises to her right accompanies the 1411 poem “Flowers Of Virtue” in its 1486 edition. Malleus Maleficarum was published in 1486, so if the original text of Flowers Of Virtue contained the incident this picture refers to, it would predate Malleus. But the original text is written in poetic medieval German and I can’t find a good translation.

When I wrote my review of the Malleus , people were surprised at the penis-stealing witch chapters. Yet nothing could possibly be less surprising; the penis-stealing witches are timeless and omnipresent. When commenters continued to doubt, I promised them this review of Frank Bures’ Geography Of Madness.

II.

Frank Bures is a journalist. In 2001, he came across an unusual BBC article: a mob had killed twelve people in Nigeria, believing them to be penis-stealing witches. A few months later, a similar article: five people, Benin. He tried to pitch a story about the phenomenon to his editor, who “said he couldn’t pay me to fly to Nigeria and find essentially . . . nothing”.

For some reason - and this is the point at which I start to worry about narrator reliability - Bures became obsessed with this. He couldn’t get it out of his mind. He started scraping together money to visit Africa on his own, story be damned:

Nigeria gnawed at me. I knew that it was a terrible time to leave. I knew that [my wife] Bridgit, newly pregnant, wouldn’t want me to go. But I also knew that I had to, and that if I didn’t it would be a lifelong regret. . . three months later, I was the lone tourist on a plane full of Nigerians descending to Lagos.

Africa is a relative newcomer to penis-stealing witches:

The first recorded incident of penis theft in Africa I could find took place in Sudan in the 1960s. But in the mid- to late seventies in Nigeria, there were waves of well-documented cases. One of these happened in the northern city of Kaduna, where a psychiatrist named Dr. Sunday Ilechukwu was working in his office when a policeman arrived, escorting two men. One of them said he needed a medical assessment: He had accused the other of making his penis disappear.

As with [a previously discussed incident], this had caused a disturbance in the street. During Ilechukwu’s examination, he later recounted, the victim stared straight ahead while the doctor examined his penis and pronounced him normal.

“Exclaiming,” Ilechukwu wrote in the Transcultural Psychiatric Review, “the patient looked down at his groin for the first time, suggesting that the genitals had just reappeared.”

According to Ilechukwu, this was part of an epidemic of magical penis theft that swept through Nigeria between 1975 and 1977. “Men could be seen in the streets of Lagos holding on to their genitalia either openly or discreetly with their hand in their pockets,” Ilechukwu wrote. “Women were also seen holding on to their breasts directly or discreetly, by crossing the hands across the chest . . . Vigilance and anticipatory aggression were thought to be good prophylaxes. This led to further breakdown of law and order.” During an incident, the victim would yell: “Thief! My genitals are gone!” Immediately, a culprit would be identified, apprehended by a crowd, and often killed.

…but it’s been making up for lost time. Bures was able to find and interview one previous penis theft victim, plus the friend of another. Both described similar stories: someone had bumped up against them under weird circumstances, they immediately noticed their penis was much smaller than usual, they called out the culprit, and - apparently because the witch involved didn’t want to get in trouble - their penis was restored.

Whatever weird itch this topic had given Bures, this didn’t satisfy him. He writes, very lucidly, about a desire to get closer to “the story”. He started bumping up against random Nigerians in suspicious ways, hoping one of them would accuse him of stealing their penis. Bures was an obvious foreigner, and a these panics often resulted in the suspected penis-stealer getting lynched, so this was a crazy thing to do. He could easily have died. Instead, everyone politely ignored him, nothing happened, and a slightly-disappointed Bures flew back to his poor family and abandoned his weird obsession.

III.

…for four years. After that the bug bit him again and he flew to Asia, long a center of penis-stealing witch activity.

There are nature documentaries on lions, dolphins, even dinosaurs. They all share a common pattern: you talk about your subject’s habitat, their diet, their behaviors. The Asian half of The Geography Of Madness has the feel of a nature documentary on penis-stealing witches. And the last beat of every nature documentary has to be: this majestic creature, which once roamed from one end of the region to the other, is now endangered, threatened by increasing globalization and industrial activity. This is true for the witches also.

Bures’ time in Hong Kong was a bust. There was a penis theft panic there forty years earlier, and he was able to interview some of the doctors who treated it. But they all said that was long ago. Now everybody is Westernized and has Western fears like vaccine injury or structural racism. They get Western mental disorders like depression and anorexia. The idea of witches stealing their penises seems as risible to them as it probably does to you.

Singapore was also a bust. Bures had hoped it wouldn’t be, because it’s full of Malaysians, and Malaysia holds a special place in history as the spot where penis-stealing witches first made contact with Western science. The Malaysian word for the condition is koro (it means “head of a turtle”, based on an analogy to the penis retracting into the body the same way a turtle’s head retracts into its shell), and it is by this name that the condition gets listed in the DSM and the rest of the medical literature. Neither I nor Bures was able to find many ethnic Malays worrying about koro ; most of the activity seems to be from Malaysian-Chinese. The Chinese definitely worry about it, attributing it to a wide variety of causes including poisoning, yin-yang imbalance, and - yes - witches. But Bures found nothing among any ethnicity. Once again, all the doctors said it used to be common, but disappeared as the city industrialized and adopted Western ways.

Guangzhou was also a bust. The doctors said the same thing - in the old days, there would be huge epidemics of koro , social contagions that would impact hundreds of people at once. Now only a few superstitious rural people still believed. One traditional healer said he saw “three or four” cases a year. All the educated people had moved on.

I once saw a nature documentary on Tasmanian tigers. Most people believe these have been extinct since 1930. Still, there are occasional unconfirmed sightings, especially in a remote area called Cape York, and every so often some scientists trudge off to Cape York with traps and cameras in the hopes of getting lucky.

Bures decides end his own nature documentary with an expedition to the Cape York of the penis-stealing witches. This is a remote island village in China called Lin’gao, where in 1984:

. . . rumors spread of a fox ghost - sometimes disguised an old woman roaming the land—collecting penises in covered baskets she carried on a shoulder pole. When two young men approached her and told her to uncover the baskets, they looked inside, saw that the baskets were filled with penises and died instantly of fright.

Panic about koro would hit a village and last three to four days. When residents heard about a case in a neighboring village, the panic would subside, since that meant the ghost had moved on. The attacks slowly made their way around the island. The ghost struck at night, when villagers were sleeping. A chill would creep into the room, and suddenly the victim would feel his penis shrinking inward. He would grab it and run outside for help. A twenty-eight-year-old office worker was at home one night when:

> “ . . . he heard a gong being beaten and the terrifying noises made by people who were panicking in a nearby neighborhood. He suddenly became anxious and experienced the sensation that his penis was shrinking. He was seized with panic and shouted loudly for help. Several men in the neighborhood rushed in and tried to rescue him by forcefully pulling his penis and making loud sounds to chase away the evil ghost that was thought to be affecting him.”

Neighbors and family members were enlisted in rescue operations. Victims were beaten with sandals and slippers while the middle finger of their left had was squeezed, so that the ghost could exit the body there.

The epidemic engulfed the island, with the exception of the Li and Miao minorities, who seemed to be immune to such fears. Researchers estimated that between 2,000 and 5,000 people were affected, but that “no one died from genital retraction.” One baby, however, did die when his mother tried to feed him pepper juice, and a girl was beaten to death during a two-hour exorcism. “Numerous men suffered injuries to their penises as a result of ‘rescuing’ actions.” Iron pins were sometimes inserted through the nipples of women to prevent retraction, which caused infections as well.

This was, as far as anyone knows, the last great koro epidemic in Asia.

Bures had a terrible time getting to Lin’gao. He had equal trouble getting an interpreter; the natives spoke a language called Be, very distantly related to Thai but not at all to regular Chinese. Finally he found someone who was able to contact a local shaman. Like any good doctor, the shaman referred him to a specialist - in this case, the designated anti-ghost shaman, who lived in a different village. He spent most of his time off on various ghost-fighting missions, but eventually Bures and his team were able to track him down.

I want you to picture the scene. An American journalist has been traveling the world in search of a dying variety of witchcraft. Now he’s reached the end of the line, the wildest and most primitive region of China. With great difficulty, he has procured an interpreter. Together, they consult a shaman, who sends them on a quest to find a second, wiser shaman who specializes in ghosts. After many trials and tribulations, he reaches the second, wiser, ghost-specialist shaman, who invites him into his home, filled with strange charms and magical images. “Tell me your question,” says the shaman. And Bures asks: “What do you know about penis-stealing witches?”

. . . and the shaman answers: “Haha, no one believes in that stuff anymore.”

IV.

So as a nature documentary, The Geography of Madness is kind of a bust. Still, Bures rescues it with some great analysis of culture-bound mental illness.

A culture-bound mental illness is one that only affects people who know about it, and especially people who believe in it. Often it doesn’t make sense from a scientific point of view (there’s no such thing as witches, and the penis can’t retract into the body). It sometimes spreads contagiously: someone gets a first case, the rest of the village panics, and now everyone knows about it / believes in it / is thinking about it, and so many other people get it too.

Different cultures have their own set of culture-bound illnesses. Sometimes there are commonalities - many cultures have something something penis something witches - but the details vary, and a victim almost always gets a case that matches the way their own culture understands it.

THESE PEOPLE ARE NOT MAKING IT UP. I cannot stress this enough. There are plenty of examples of people driving metal objects through their penis in order to pull it out of their body or prevent the witches from getting it or something like that. There is no amount of commitment to the bit which will make people drive metal objects through their penis. People have died from these conditions - not the illness itself, which is fake, but from wasting away worrying about it, or taking dangerous sham treatments, or getting into fights with people they think caused it. If you think of it as “their unconscious mind must be doing something like making it up, but their conscious mind believes it 100%”, you will be closer to the truth, though there are various reasons I don’t like that framing.

In Rajasthan, India, people come to the hospital with gilahari (lizard) syndrome. Patients say a lizard-like mass, sometimes visible as a skin swelling, is crawling around the body. They express terror that it will reach their airway and suffocate them.

Japanese people may contract jikoshu-kyofu, a debilitating fear that they have terrible body odor. No amount of reassurances by friends and psychiatrists can convince these people that they smell normal, nor will any number of deodorants or perfumes make them comfortable.

The French suffer from bouffée délirante, where a perfectly healthy person suddenly becomes completely psychotic, with well-formed hallucinations and delusions - then recovers just as suddenly, sometimes over hours or days. This is not how psychosis works anywhere except France and a few former French colonies.

Traditional Chinese medicine monitors the balance between yin and yang. The male orgasm can deplete yang, and sure enough in China (but nowhere else) some men suffer traditional symptoms of yang depletion after they orgasm. “The symptoms can last weeks to months after a single orgasm, [and include] chills, dizziness, [and] backache”.

The phrase “run amok” comes from Malaysia, where it referred to a specific phenomenon: some person who had been unhappy for a long time would suddenly snap, kill a bunch of people, then say they had no memory of doing it. Malaysian culture totally rolls with this and doesn’t hold it against them; the unhappiness is a risk factor for possession by a tiger spirit, which commits the killings. Although Malays have been doing this since at least the 1700s, there are some fascinating parallels with modern US mass shootings that suggest the damn tiger spirits have finally made it to the US common psychological origins.

I have seen exactly one demonic possession case in my ten years as a psychiatrist. The man fell to the ground, mouth foaming, chanting strange syllables and the names of Biblical demons. My attending doctor at the time - one of those people who somehow manages to be an expert in everything - was an expert in demonic possession, and told us that he was in no way psychotic, antipsychotics wouldn’t help him (except insofar as they help everyone by decreasing all behaviors), and he needed to “work through his issues”. The patient was uncooperative - he was only visiting MDs because the local bishop wouldn’t call in an exorcist until he got a psych exam - and eventually left against medical advice.

After going down the list, Bures asks the correct next question: how do we know whether or not our own mental illnesses are just as culture-bound as the Japanese or Malaysians’? Cultures that believe in witches have witch-related culture-bound illnesses; cultures that believe in demons have demon-related ones. We believe in science, so we should expect sciencey-sounding culture-bound illnesses, and these might be hard to tell apart from other, more physical conditions. So how suspicious should we be, and of what?

Certainly we have some culture-bound mental illnesses. Electromagnetic hypersensitivity is a condition where some people supposedly become very sick when exposed to electromagnetic fields (like from cell phones). This sounds very scientific and makes perfect sense according to our culture, but researchers have found that placebo electrical devices make them exactly as sick as real ones, and that devices they don’t know about don’t make them sick at all. These people’s pain is real, and their lives are very difficult (although a few have found refuge in the National Radio Quiet Zone, an area in Virginia where the government enforces a ban on electromagnetic transmissions for secret military reasons). But their condition only afflicts them because they believe in it, much like with koro.

Fine, everyone knows that one’s not real. What about DSM-style mental disorders, the stuff everyone’s supposed to believe in? Are those culture-bound?

Unfortunately, I think Bures kind of flubs this section. He decides to focus on PMS (premenstrual syndrome), which is officially included in the DSM as PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder). After discussing the history of hysteria, he writes that:

Today, hysteria is never diagnosed, except by unwise husbands. In 1931, however, an American gynecologist named Robert Frank revived the idea in a new guise. He published an article titled, “The hormonal causes of premenstrual tension.” Frank described symptoms that occurred in the week before menstruation: irritability, bloating, fatigue, depression, attacks of pain, nervousness, restlessness, and the impulse for “foolish and ill considered actions,” due to ovarian activity. Again, the cause was the uterus.

Then in 1953, British physician Katharina Dalton elaborated on this, arguing the condition came from fluctuation of estrogen and progesterone. She called it Premenstrual Syndrome, and soon symptoms grew to include: anxiety, sadness, moodiness, constipation or diarrhea, feeling out of control, insomnia, food cravings, increased sex drive, anger, arguments with family or friends, poor judgment, lack of physical coordination, decreased efficiency, increased personal strength or power, feelings of connection to nature or to other women, seizures, convulsions, asthma attacks, not to mention flare ups in asthma, allergies, sinusitis, anxiety disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, and multiple sclerosis.

If any of these symptoms occurred in the second half of the menstrual cycle, one had PMS. Estimates of the number of women afflicted ranged from 5 percent to 95 percent.

In the 1980s, three women in the UK were tried for arson, assault and manslaughter. The three all claimed they had diminished responsibility due to PMS, and got reduced sentences on the condition that they underwent hormone treatment.

After that, according to one study, American women flooded doctors with requests for help with their PMS. “Popular groups like PMS Action were founded to promote recognition and treatment of PMS by medical professionals. Private PMS clinics began to appear in the USA, modeled after those in the UK, and progesterone therapy was enthusiastically adopted, much to the chagrin of many gynaecologists who viewed its use as ‘unscientific’ and ‘commercial’, not to mention unlicensed.”

Based on all this, the 1987 version of the DSM-III included a new category: Late Luteal Phase Disorder (luteal refers to progesterone). It was proposed as a topic for further research, but despite the absence of such research, it was included in the 1994 edition of the DSM-IV under the name Premenstrual Dysmorphic Disorder, or PMDD.96 In 2013, in the DSM-5, it was given its own category as a full-fledged mental illness.

Yet neither PMS nor PMDD occur in most cultures. There are no biomarkers to measure them by. No conclusive correlation has ever been found between estrogen or progesterone levels and PMS.

As one study noted, “the more time that women of ethnic minorities spend living in the United States, the more likely they are to report PMDD. Thus, if we are to accept PMDD as a reified medical disorder, then we must also accept exposure to U.S. culture as a risk factor for contracting PMDD.”

If it is a syndrome at all, it’s a cultural one.

I asked my wife what she thought of this, and she told me:

-

The day before her first-ever period, as a teenager, when she had never really thought about PMS, she felt exceptionally weird, emotional, and generally off, to the point where it seemed to demand an explanation. Then she had her first-ever period, and retroactively explains it as PMS.

-

Sometimes when she is overly emotional, her mother tells her “you’re PMS-ing”, and she is always right, even though her mother is not keeping track of her period in any way and has no way of guessing beyond emotional symptoms.

-

She reminded me that yesterday she was unusually grumpy, so much so that she had apologized to me for it and tried to come up with explanations - and then later yesterday she had her period.

Meanwhile, Bures’ counterargument is - what? That it sounds kind of sexist to accuse female hormones of making women overly emotional? Hasn’t he ever heard of stereotype accuracy? That people asked their doctors to be treated for it more often after they knew it was considered a medical condition, and was treatable? That seems to have a much simpler explanation! That there are no biomarkers? There are inconsistent biomarkers that work sometimes but not other times, just like for schizophrenia, epilepsy, cancer, and half the other conditions in medicine. That these conditions don’t occur in most cultures? From here:

A World Health Organization (WHO) study on menstruation (1981) surveyed 5,322 women from Egypt, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Korea, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, United Kingdom and Yugoslavia. . . The majority of women in all cultures report some premenstrual physical discomfort in addition to negative mood changes, however fewer women report mood change than physical change. The main cross-cultural difference was in the prevalence of specific symptoms.

Immigrants to the United States report more PMDD the longer they’re here? True (source), but it’s a matter of degree, and seems more true of the PMDD diagnosis than specific symptoms. The diagnosis requires impairment, which is subjective. I imagine an immigrant from a culture where mental disorders are unthinkable - something that only happens to a few psychos in asylums - and where you work 12-hour days in sweatshops. Someone asks her “hey, has this mental disorder ever prevented you from working?”, and she says no, because obviously you grit your teeth and work through the symptoms. And I imagine an American seeing the same question and saying “Yeah, I did decide I had to take a couple of sick days because of that.” I’m not saying this definitely happened, just that it’s a possibility.

Meanwhile, this entire area of study is a mess. The “PMDD is culture-bound” hypothesis was originally invented by feminist scholars trying to argue that the diagnosis was a sexist attempt to pathologize women as overemotional and untrustworthy (this is also where Bures got his “it’s just hysteria by a different name” idea). See for example here and here, the second of which says that “the feminist argument is that if women are angry/distressed, it is for good reason, not due to pathology”. Bures somehow swallowed and repeated this, and then some feminists on Vox wrote an article attacking him as a “male writer” who was denying women’s lived experiences of PMS and stereotyping them as stupid and gullible. Neither side has an argument beyond “I can think of a reason it would be sexist for people to disagree with me” and neither side will acknowledge that the other side is also feminists basing their argument entirely on how it would be sexist to disagree with them. Everything in every area of social science has been like this for at least the past twenty years.

But also, this highlights the difficulties with declaring something culture-bound. How do you know if something’s culture-bound, vs. people don’t notice it or mention it if they don’t have a name for it? How do you know if something’s culture-bound vs. some cultures consider it too embarrassing or taboo to think about? How do you know if something’s culture-bound, vs. people will go to doctors about it if they think doctors can treat it, and otherwise they won’t?

I’ll discuss these questions more later, but I want to finish Bures’ argument. He gestures at a few other possible candidates for culture-bound mental disorders, including repetitive strain injury and chronic pain. But he quickly moves on to a long section that tries to establish the reality of “voodoo death”, ie the thing where if you believe you are going to die hard enough, you actually die. I think most arguments for voodoo death are pretty bad, and I didn’t find Bures’ convincing. But bonus points for referencing a study claiming that chronically stressed people only die at higher rates if they believe chronic stress is bad for them, and if not then they don’t (this is not really how I interpret the abstract, but I haven’t looked closely)

Is it weird to stay on the crazy train long enough to agree that cultural effects are strong enough to make you think witches are stealing your penis, and then get off it once people start talking about voodoo death? I think no - these are very different situations. Believing in koro can make you hallucinate that your penis is shrunken or gone, but no belief, however strong, can (directly) remove your penis itself. Culture → beliefs is fine; culture → reality is a step I’m not willing to take.

V.

Since I rejected Bures’ PMDD example, I want to digress to what I think is a stronger argument: anorexia, which Ethan Watters discusses in his book Crazy Like Us.

Anorexia was mostly unknown in the West, until becoming “trendy” in the mid-1800s. During that period, doctors reported high prevalence of anorexia among “hysterics”, but the fad ended after about ten or twenty years, and it went back to being basically unknown. In 1983, famous singer Karen Carpenter died of anorexia, thrusting it back into the national news, and suddenly lots of people (in the West) were anorexic again.

Meanwhile, foreign doctors who trained in the West went back to their home countries, searched far and wide for it, and found almost nothing. The few cases they did see didn’t resemble the typical Western version at all - for example, one Hong Kong psychiatrist was able to find a woman who refused to eat out of grief when a boyfriend left her, but she didn’t think she was fat, or feel any cultural pressure to be thinner. The absence of anorexia abroad was especially surprising since anorexics tend to end up in the hospital with extremely noticeable malnutrition that doesn’t really mimic anything else. It’s not really possible to hide severe anorexia the way you can hide severe depression.

In 1994, Hong Kong got its own Karen Carpenter - a young girl died of anorexia, setting off a national panic and many public awareness campaigns. Near-instantly, anorexia rates shot up to the same level as the West, with the appropriate number of people presenting to hospital ERs with severe malnutrition.

This story raises a lot of questions. For example: where did the first anorexics (Karen Carpenter, the girl in Hong Kong) come from? Why anorexia and not something else? And how come knowing about anorexia makes it spread so quickly?

VI.

Past this point I’m using this review to discuss my own thoughts, not Bures’ or Watters’.

“Culture-bound” is less all-or-nothing than you’d think. Look hard enough, and you’ll find people having “culture-bound syndromes” from cultures they’ve never heard of.

Ntouros et al in Thessaloniki describe “ koro -like symptoms in two Greek men”. One, a paranoid schizophrenic:

. . . reported for the first time a sensation that his penis retracts into the abdomen and a fear that it will subsequently be lost. This would be accompanied by anxiety and sadness pertaining only to the loss itself. He would then proceed to search manually for his penis and masturbate. No pleasure was gained by masturbation, but the anxiety would be lifted.

Romero et al describe a case of koro in “an intellectually disabled Caucasian patient” in Spain. They write that “although it is widely regarded as an epidemic in South-east Asia, there are some isolated cases in other cultures as well.”

Wilson and Agin describe a 29 year old white male from New York, “not exposed to the Chinese culture”, who went to the doctor with a five month history of worrying that his genitals were retracting into his body:

Sometimes, he would manually reaffirm the presence of his genitals. Occasionally he would, in private, remove his garments and visually confirm the presence of his genitals. On one occasion, while taking the train home from work, he experienced an acute exacerbation of these symptoms. His pain increased from 3/10 to 10/10, and he felt as if his genitals had fully retracted within his belly. Upon reaching his hometown, he immediately went to the local hospital emergency room where examinations for inguinal hernia, urinary tract infection, proctitis, prostatitis, and testicular disorders proved negative.

He improved significantly on the anti-anxiety medication desipramine.

Chowdhury surveys the evidence on koro and divides the condition into two types: culture-bound and non-culture-bound. The culture-bound type usually goes in large epidemics, hundreds to thousands of people, in koro-believing parts of Africa and Asia; the victims were usually previously psychologically normal. The non-culture-bound type hits a few scattered individuals, is not contagious, and can happen anywhere - Greece, Spain, America. Some patients are psychologically normal, but there are a disproportionate number of schizophrenics, drug users, brain damage victims, and other previously-mentally-ill people.

Other culture-bound illnesses seem to be like this too. Running amok has been big in Malaysia for 300 years. The Columbine shooters seem to have been autocthonous American cases, equivalent to that one New Yorker who got koro - before their fame inscribed amok onto the US collective consciousness the same way Karen Carpenter’s inscribed anorexia. Japan’s jikoshu-kyofu affects occasional victims in the US under the name olfactory reference syndrome. Watters admits there were a tiny handful of unusual anorexia cases in Hong Kong before Westernization. And even that Indian there’s-a-lizard-in-my-skin condition differs only in species from delusional parasitosis.

Delusional parasitosis - the false belief that you are infested with parasites and can feel them crawling in your skin - is actually an especially interesting case. Two groups are disproportionately represented among patients: menopausal women and cocaine addicts. Relatedly, two biological conditions that can sometimes cause weird skin sensations that feel like crawling insects are . . . menopause and cocaine use. So there’s no mystery here. But, also represented among delusional parasitosis patients are the roommates and family members of these people. The index case hallucinates insects for a well-understood biological reason; their close contacts hallucinate insects through social contagion.

So a unified theory of these conditions might be:

-

Some people have the condition for a normal biological or psychiatric reason. For example, someone might believe a lizard is crawling under their skin because they use cocaine, which causes hallucinatory crawling sensations. Or someone might believe their penis is missing because they’re schizophrenic, which makes them naturally hallucination-prone.

-

Sometimes these people’s friends and family hear about the condition, and get it through some kind of social contagion.

-

Sometimes this reaches a critical mass where the condition gets processed through the local culture. For example, if your culture believes in witches, people come up with a whole mythology about how these witches sometimes steal penises. If your culture believes in science, they come up with a whole theory about how the Lyme disease spirochete can persist even after apparently successfuly treatment and cause chronic Lyme disease. If your culture believes in feminism, they talk about how patriarchal beauty standards cause women to have an uncontrollable urge to diet themselves to death in order to look sexy for men.

-

This belief primes people to experience the condition, and makes it much more common than it would be if it were just a few schizophrenics having random hallucinations now and again.

The weak points of the theory are surely (2) and (4) - what does it mean to “prime people” for the condition? I want to talk about three interpretations:

A ) Sensitization

Megabytes of data assault the brain every second. How does it decide what to focus on when building world-models? Predictive-coding says: it uses pre-existing categories/narratives/guesses to determine what’s most likely to be important.

You probably know what this is - but if not, watch it before going further:

If you’re sensitized to the idea that there might be a gorilla, you’ll see it. If not, you won’t.

My own experience with sensitization: every so often my house gets infested by ants and some of them crawl on me. Then I get rid of the ants, but even after they’re gone, for a couple of weeks I can still feel hallucinatory ant-crawling feelings on my arms. You can think of this as setting a threshold that balances false positives and false negatives - my nervous system will always be noisy, get random itches, etc, when do I interpret any particular pattern of impulses as a crawling ant? If I set the threshold too high, I will miss real ants; if I set it too low, I will get fake ants. Presumably there’s some optimal threshold, and that threshold is lower when I know there are ants around and probably one will crawl on me soon. Somehow my brain does the proper Bayesian math under the hood, and so I am afflicted with a few weeks of false positives. Honestly I am getting away lucky; in delusional parasitosis this becomes a trapped prior and they feel it forever.

Bodily sensations seem to be especially sensitive to this. For example:

-

Try interpreting your current experience through the category/guess/narrative of “there’s something wrong with the way my tongue is lying in my mouth right now, and it’s actually quite uncomfortable and attention-grabbing.”

-

Try interpreting your current experience through the category/guess/narrative of “there’s an itch on the back of my neck”.

-

Try interpreting your current experience through the category/guess/narrative of “it’s suddenly impossible to breath automatically, I have to breathe manually and every time I do I’m getting it subtly wrong.”

-

Try interpreting your current experience through the category/guess/narrative of “I need to yawn right now.”

Chronic pain is a unfortunately a bog-standard sensitization problem plus trapped prior; panic disorder is probably something similar. I have some kind of misophonia (extreme irritation/sensitivity to sound) that as far as I can tell got significantly more severe after someone told me “you’re really sensitive to sound, aren’t you?” Probably I had always been slightly sensitive, but now I was in some sense sensitive to being sensitive , and looking for it , and that was worse.

B ) Reinterpretation of ambiguous stimuli

This is probably the same thing as sensitization, just considered on a different level.

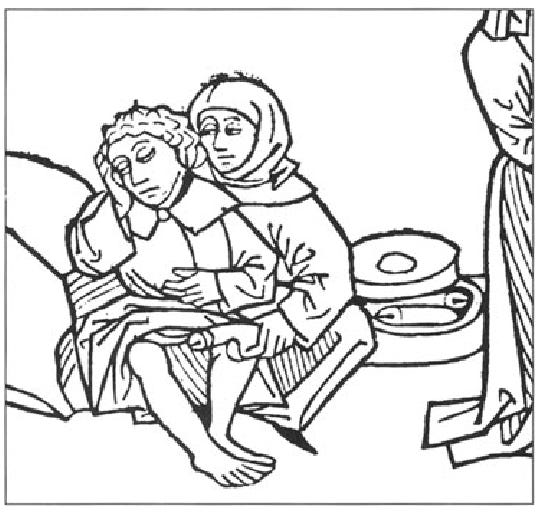

Look at these pictures and try to figure out what they are. Too hard, right? They’re ambiguous; you have no category/guess/narrative/framework that gives you a foothold.

Now look at the answers, and look again. If you’re like me, they jump out at you. They make perfect sense, figure is effectively separated from ground, it’s not just that you intellectually know what they are, it’s that your visual cortex has fundamentally levelled-up its ability to perceive them.

Those pictures have one clear best solution; others don’t.

Is cube 1 the same as cube 2 or cube 3? You can make an effort of conscious will that changes your perception by altering which category/guess/narrative/framework you apply.

These two examples are weak, because vision is a really good sense which is hard to fool and rarely permits true ambiguity. I like comparing it to something we’re genuinely bad at, like cognition. Byte-for-byte, your visual field might have the same amount of data as a history book. But people can read a history book and interpret it any number of ways. Some see History as a monotonic rise from barbarism to high culture, others as a monotonic fall from Eden to the despair of modernity. Some see it as the World-Spirit groping towards the utopia of Communism, others as a technocapital singularity struggling to birth itself. Some see it as a giant Jewish conspiracy, others as being guided by the hand of God, others as one million examples of liberals always being right and conservatives always being wrong, others as the exact reverse. Depending on their starting category/guess/narrative, people can look at history and see all kinds of things!

Imagine the picture above, except instead of a normal cube, it’s a 2000-dimensional irregular hyperfractal with a million potential interpretations. When viewed from the right angle, with the right preconception, it looks exactly like a witch stealing your penis.

C ) Signaling spirals

This is the odd one out - a bit more speculative, more Hansonian than Fristonian.

Suppose there’s an event where a good person would have some emotion. For example, if your parents die, probably a good person would be at least a little sad. You want to signal that you’re a good person - specifically, slightly better than average.

If, in your culture, everyone knows that you mourn for a week after your parents die and then you’re mostly okay, then in order to signal well, you only have to mourn for about a week.

If, in your culture, everyone knows that you mourn for five years and are utterly miserable that entire time, probably best to mourn for five years and be utterly miserable, or people will think you didn’t love your parents, or you’re an emotionless sociopath, or something else bad.

As per Trivers, the emotional brain doesn’t trust the rational brain, and handles a lot of its signaling under the hood. So you’re not calculating any of this, you’re just feeling it.

Suppose that someone spreads the cultural belief that parental death is horrible, the most horrible thing imaginable, and normal people have total mental breakdowns when their parents die. Everyone who believes this and is trying to signal properly will have a total mental breakdown when their parents die. Meanwhile, people in other cultures without this belief will get through their parents’ deaths relatively gracefully.

The ancient Romans loved war. If you loved war, and killed a lot of people, that made you glorious. Nobody worried it meant you were a bloodthirsty psychopath. Or if you were, it’s fine! The past twelve emperors were bloodthirsty psychopaths! Their families, concubines, and guards were all bloodthirsty psychopaths! You’ll fit right in! Relatedly, it doesn’t seem like the Romans had PTSD.

In our society, it’s commonly believed that War Is Hell, and if you enjoy it too much, you might be a bloodthirsty psychopath. Relatedly, estimates of what percent of veterans get PTSD range from 15% to 85%. I’m not sure the 85% number is accurate, but if it was, and I was a veteran, and I wasn’t getting PTSD, I might start worrying that this was starting to signal negative things about me. If my unconscious felt the same way, maybe I’d develop a few PTSD symptoms, just to be safe.

We’re conducting a massive experiment in how far you can take this. People now believe that you can be traumatized by hearing someone express the wrong opinion during a college class - and that intellectuals with sensitive souls and diverse equity-loving justice-promoting minorities will be traumatized most of all. I suspect all of this is true, if you believe it.

VI.

The sun rises in the east, sets in the west. Snow falls in winter, melts in spring. With the certainty of natural law, I know two things. People will ask “Okay, so which of our mental disorders are culture-bound?” and “it’s definitely gender dysphoria, right?”

Let’s start with the first question.

The only possible conclusion from section V is “it’s a spectrum”. All perceptions and inferences, including disordered perceptions like “my penis is retracting into my body” and disordered inferences like “it must be witches” come from a combination of the real bottom-up sensations we get and the categories/guesses/narratives we use to interpret them.

I assume men get proprioceptive impulses - the kind of sensory data that tells people where their body parts are - from their penis. I assume that as the the penis gets more or less erect - or just more or less tense, encumbered by different amounts of clothing, etc - the the proprioceptive impulses vary. Sometimes they vary to a very low level, where it feels like the penis is much smaller than usual. A healthy person, with no reason to believe this, will ignore it, for the same reason you ignored me duplicating the word “the” as “the the” several times in this paragraph already. It’s impossible, it doesn’t make sense, so the brain will just throw it out.

An unhealthy man - for example, with schizophrenia - won’t do that. He might think his penis is smaller than usual. Probably this will only last however long a proprioceptive impulse lasts - a short amount of time - but it could become a low-grade trapped prior. Then this man will have the boring, non-culture-bound version of koro, where he goes to a hospital and the doctors excitedly write a paper on how a white guy with no connection to Chinese culture got this culture-bound syndrome for some reason.

But if someone has been sensitized to the possibility of his penis retracting into his body, or taught to interpret ambiguous sensory stimuli that way, it will take a much smaller proprioceptive error to trigger the problem. Maybe a perfectly ordinary amount of random noise will do it - just like when I had a strong prior on insects crawling on my body, I could feel them crawl. Now you have the socially contagious version of koro, which forms epidemics and affects thousands of people at a time.

Meta-cultural-beliefs affect what cultural beliefs you can form. A meta-cultural-belief like “Western science” says that penises retracting into the body is impossible and witches aren’t real. People under the influence of this meta-cultural-belief never come close to forming the cultural belief in koro. On the other hand, a meta-cultural belief in magic and witchcraft makes that cultural belief more likely.

“Okay, but in our society, most of the time, which conditions are real vs. culture-bound?”

Even with these clarifications, it’s still a spectrum. You can imagine a person whose case is 100% biologically real, 0% culture-bound. For example, a cocaine user who never considered the possibility of parasite infestation, but the cocaine is (through purely chemical effects) stimulating his nervous system and making him feel crawling sensations.

You can also imagine a person who’s 0% biologically real, 100% culture-bound. For example, that cocaine user’s roommate, who never touched cocaine, but once her roommate says he has a parasite infestation, she starts feeling the symptoms too.

I think most people will be in the middle. For example, believing that insects exist is probably a cultural risk factor for delusional parasitosis. So nobody is really 100% biological, 0% culture-bound. And there are probably one thousand obscure sodium channel genes with names like BLRG2 that increase the nerves’ ability to maintain a crawling sensation. So nobody is really 0% biological, 100% culture bound. You can imagine a trap house where 100% of people are using cocaine, but only half have delusional parasitosis; probably some genetic or cultural risk factor is determining who gets it. Or you can imagine a barracks where a socially contagious epidemic of delusional parasitosis is spreading rapidly and affecting 50% of recruits; again, everyone has the cultural risk factor, and probably other beliefs and genetics are determining who gets it and who doesn’t.

I think koro is culture-bound in the sense that, in cultures that believe in koro, people get it hundreds of times more often than in cultures that don’t. This doesn’t mean it has no biological risk factors, or that nobody ever gets it without knowing about it, but it suggests that the cultural belief is an important intervention if you want to prevent spread.

“Okay, but in that sense, where you compare how often the conditions happen in our culture compared to a hypothetical one where nobody had ever heard of them and then see how different the two cultures are, which DSM conditions are more real vs. more culture-bound?”

Fine. With very very low confidence, and the knowledge that I will get at least some of this wrong in a way people will unavoidably find terribly offensive, I would wildly guess something like:

-

Schizophrenia: 90% biological, 10% cultural

-

Bipolar: 75% biological, 25% cultural

-

Depression, anxiety: 50% biological, 50% cultural

-

Anorexia, PTSD: 20% biological, 80% cultural

-

ADHD: our conception of this is too confused for the question to make sense

“Okay, but gender dysphoria?”

Hopefully now the answer is obvious: it is and it isn’t. People have been having gender identity crises since the beginning of time. There’s some evidence some of this is biological; people with closer to opposite-sex hormone profiles and so on are more likely to end up transgender, and very off-base hormone profiles seem to produce gender issues pretty consistently. But in our modern society, which has a category/guess/narrative around this, it seems to happen orders of magnitude more often than in other societies. And in societies with different categories/guesses/narratives, it happens differently - a lot of people who are transgender today would have been cross-dressers or lesbians 30 years ago.

(schizophrenics remain overrepresented among transgender people today - maybe 5-10x expected rate - and a few papers suggest they were more overrepresented in the past when transgender was less common. I think this is for the same reason that, in cultures without a native koro tradition, a disproportionate number of koro cases happened in schizophrenics. Schizophrenics’ brains don’t use categories/guesses/narratives in normal ways, and they end up in kind of random places, whereas everyone else mostly ends up where their culture guides them)

Before anyone gets too excited about this, I want to stress a version of the point Bures got right earlier: there is no neutral culture. Having lots of transgender people is downstream of cultural choices. But having lots of cisgender people is also downstream of cultural choices. There isn’t infinite flexibility - evolution ensures a bias towards heterosexuality, for obvious reasons. But there’s a lot of flexibility - Spartan men married and had sex with women, but they thought this was a dumb annoying thing they had to do to have children, and sex with young boys was the obvious enjoyable satisfying option. Even within evolution’s constraints, culture can do some pretty weird stuff. I think you could probably have a culture where 99% of people were transgender, where it was generally accepted that everyone transitioned on their 18th birthday, and where only a few people (disproportionately schizophrenic) would object or see anything wrong with this.

So fine, yes, gender dysphoria shares some resemblance to culture-bound illnesses; I would put it around the same level as anorexia. But be careful: everything shares some resemblance to everything. What if transphobia is our culture’s version of the penis-stealing witch panic? Wise but evil women (gender studies professors) are using incomprehensible black arts (post-modernism) to make people lose their penises. Sure, those people are losing their penises through voluntary sex-change surgery, but this is just another case of the general principle that we replace the magical explanations natural to other cultures with the medicalized explanations natural to our own. And sure, other culture’s panics involved fake/illusory penis loss and ours involves the real thing, but this is just another case of the general principle that modern Western civilization turns other culture’s myths into reality. When they were telling tall tales about men who flew like birds, we went ahead and invented the airplane; when they imagined golems, we created working robots. Now we’ve finally gotten around to penis-stealing witches.

America really is the greatest country in the world.