Book Review: The New Sultan

I.

If you only learn one thing from this post: it’s pronounced “air-do-wan”.

If you learn two things from this post, learn that, plus how a country which starts out as a flawed but somewhat-liberal democracy can lapse into near-dictatorship over the course of a few years.

I got The New Sultan: Erdogan And The Crisis Of Modern Turkey because, as a libertarian, I spend a lot of time worrying about the risk that my country might backslide into illiberal repression. To develop a better threat model, I wanted to see how this process has gone in other countries, what the key mistakes were, and whether their stories give any hints about how to prevent it from happening here. Recep Tayyip Erdogan transformed Turkey from a flawed democracy to a partial dictatorship over the past few decades, and I wanted to know more about how.

As an analysis of the rise of a dictator, this book fails a pretty basic desideratum: it seems less than fully convinced the dictator’s rise was bad. Again and again I found myself checking to make sure I hadn’t accidentally picked up a pro-Erdogan book. I didn’t; author Soner Cagaptay is a well-respected Turkey scholar in a US think tank who’s written other much more critical things. The fact is, Erdogan’s rise is inherently a pretty sympathetic story. If he’d died of a heart attack in 2008, we might remember him as a successful crusader against injustice, a scrappy kid who overcame poverty and discrimination to become a great and unifying leader.

I want to go into some of this in more depth, because I think this is the main reason why Erdogan’s example doesn’t generalize to other countries. What went wrong in Turkey was mostly Turkey-specific, a reckoning for Turkey’s unique flaws. Erdogan rose to power on credible promises to help people disenfranchised by the old system; by the time he turned the tables and started disenfranchising others in turn, it was too late to root him out. If there’s a general moral here, it’s that having the “good guys” oppress and censor the “bad guys” is fun while it lasts, but it’s hard to know whether you’re building up a karmic debt, or when you’re going to have to pay the piper.

Given how hard it is to convince people of that moral, let’s go through the full story in more detail.

II.

Medieval Turkey was dominated by the Ottoman Empire, officially an Islamic caliphate though in practice only inconsistently religious, ruled by autocratic sultans and a dizzying series of provincial governors. As time passed, they fell further and further behind Western Europe; by World War I, they were a mess. As the stress of the war caused the empire to fracture, General Mustafa Kemal seized power, reorganized the scraps of Ottoman Anatolia into modern Turkey, and was renamed ATATURK, meaning “Father of Turks”.

Ataturk was born in Ottoman-controlled Greece, and was typical of a class of military officers at the time who were well-educated and “Europeanized”. He wanted to turn backwards Turkey into an advanced Western country - and Western countries were mostly secular. He saw Islam - the religion of the old Ottoman Empire - as a roadblock, and passed various laws meant to relegate it to the margins of public life.

(my favorite Ataturk story, probably apocryphal, was that he passed a law banning women from wearing hijabs. Nobody followed it and the police wouldn’t enforce it, so he passed a second law requiring prostitutes to wear hijabs, after which other women abandoned them. As far as I can tell this is an urban legend, but it captures the spirit of the sort of measures he took to drag Turkey, kicking and screaming, into secular modernity.)

The Turkish Armed Forces were Ataturk’s power base, and was mostly made of well-educated Europhiles like himself. When he moved Turkey toward democracy, he charged the military with ensuring it never deviated too far from his original vision. But Turkey was demographically dominated by poor Muslim peasants and naturally tended towards Communism or Islamism. So the cadence of Turkish democracy was a gradual drift towards one of these extremes, followed by the military staging a coup to undo the damage and restore secular cosmopolitan liberalism. There were four such coups between 1960 and 2000 - including “coups by memo”, where the military would say “let’s pretend we just held a coup” and the civilian government, unwilling to risk a real coup, would resign en masse.

Secular education was a pillar of Ataturk’s plan, one of the lines that a government couldn’t cross without risking military retribution. There was one exception: future clerics needed a religious education, so the government allowed a few religious schools - called Imam Hatip schools - to train this demographic. To prevent them from becoming too powerful, the state formally stigmatized their graduates. They wouldn’t be allowed in good colleges (in later years, Imam Hatip graduates had a fixed number of points subtracted from their college entrance exam scores!) and an Imam Hatip degree would be useless for most jobs. For religiously-trained students, it was either cleric or nothing, no chance to change your mind.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan was born in 1954 in Kasimpasa, an Istanbul slum with the same kind cultural cachet in Turkey that Eight Mile Road or Compton has in the US - a place where you have to be tough to survive. His family were recent immigrants from Turkey’s equivalent of the Bible Belt, and figured young Erdogan needed strong values if he was going to resist the temptations of the big city. They decided to send him to an Imam Hatip school, even though it meant throwing away his future.

Erdogan’s classmates were a lot like him - the sons of religious families who had made a calculated choice to raise their kids Muslim even if it meant torpedoing their career prospects. This was the age of Necmettin Erbakan, a Muslim politician who wanted to overturn Turkey’s state-sponsored discrimination against observant Muslims, and the Imam Hatip kids were big fans. Young Erdogan decided that supporting Erbakan’s crusade was his life’s work, so with a year to go before graduating, he transferred to secular public school in order to get a degree that would allow him to participate in normal society and take a job in Erbakan’s party. He rose through the ranks, and his efforts paid off - in the mid-1970s, Erbakan made it to Parliament, a major achievement for an openly Islamist politician. In 1980, the military decided they had seen enough, held a coup and arrested 650,000 (!) supporters of the old government, including Erbakan. After killing and torturing a few thousand people who resisted, the military declared that Islamic parties were extra-illegal and Erbakan was personally banned from politics for ten years. They also wrote a new constitution saying no party could enter Parliament without 10% of the vote, widely considered too high a bar for Islamists or other fringe parties to meet. Erdogan was pretty devastated, and retired from politics for a while, briefly finding work as a confectioner and a semi-professional soccer player.

But in the early 1980s, the military started working on returning the country to civilian rule. Fearing Communism, they decided to loosen some of the restrictions on Islam, seeing Muslims as potential allies against the left. Erbakan was nod-nod-wink-wink allowed to return to politics, and Erdogan returned as his lieutenant.

Erbakan’s Islamic Party rushed into a gap made by collapse and infighting among more established parties. When the generals had banned politics after the coup, brave resistance leaders in various parts of the political spectrum had started secret parties in defiance of their orders. When politics became legal again, the secret resistance parties refused to step back and let the pre-coup parties take over again, meaning that for a while there was a pre-coup center-left party vs. a secret resistance center left party, a pre-coup liberal party vs. a secret resistance liberal party, etc. The infighting weakened the traditional parties. The Islamists were almost the only ones left - and they nominated Erdogan for mayor of Istanbul.

Remember, Erdogan was a former semi-professional soccer player, and a child of the city’s worst slum. He is actually a man of the people. His opponents were mostly elite Westernized pawns of the military who “sip cocktails” “in Nisantasi hotels” (I don’t know what this means, but it sounds bad). So he had an advantage early on. His disadvantage was that Turkey is really suspicious of political Islam; even though most Turks were nominally Muslim, they suspected Erdogan’s party of foreign-influenced Taliban-style fundamentalism. Erdogan went on a charm offensive to prove them wrong:

His was a common-sense Islam, the same kind that “real” Turks cherished […] He took photo opportunities at meyhanes - tavern-style Turkish restaurants where alcohol flows freely - and he even pulled publicity stunts by visiting Istanbul’s legal brothels. Standing among the gobsmacked sex workers, he insisted that most of them would support the RP [his party] and its conservative mission, since it was the only party that would rescue them from their trade […]

In the rhetoric of the new RP, condemning Turks for their wayward lifestyles took a backseat to castigating the establishment and the West for Turkey’s ills. By shifting the blame this way, Erbakan hoped to reach audiences that previously had been put off by the Islamists’ accusatory jeremiads. This new message also came with new optics: RP television ads began to feature people who seemed to come from all walks of life, and who evinced varying levels of piety. Even uncovered women went on display. Filiz Ergun, a dentist and council member in the Istanbul district of Gungoren who became one of the faces of the new RP, did not cover her hair, and she insisted that the party embrace modern professional women like her. A bigger stir was made when Gulay Pinarbasi, a fashion model and actress, joined the party in 1993. She began covering her hair, and pledged to live a completely different life in line with the teachings of “Islam”.

Erdogan lost his first two elections. But before his third, both of the major competing parties collapsed in near-identical corruption scandals. First, the center-right mismanaged the economy and was found to be stealing a lot of money and giving it to their own officials. Next it was the leftists’ turn. The leftist mayor of Istanbul bungled a strike by sanitation workers, causing mounds of garbage to build up around the city. Finally:

The problem reached an unimaginable level of morbid absurdity when one of the trash heaps that were slowly engulfing a slum neighborhood exploded. Methane gas had built up beneath the filth, finally igniting and causing an avalanche that killed 27 of the hapless poor.

Getting murdered by explosive piles of your own feces is already kind of an on-the-nose metaphor for life. But it got worse: credible sources revealed that the leftist official in charge of sanitation was taking all the money that he was supposed to be using to prevent this kind of thing and using it to have an affair and bribe his wife to stay quiet (he must have under-bribed her; she was the credible source). This was the end of the leftists as a meaningful force in Istanbul politics.

With everyone else discredited, Erdogan had an opening. But also, people were starting to think that everyone else was so corrupt that maybe having some pious religious people with strong values in charge was exactly what they needed, especially if they were willing to relax on the no-sex-or-alcohol stuff. Also, the Islamists had been powerless for so long that their party wasn’t enriched for power-seeking psychopaths the same way as all the other parties. Erdogan finally got elected Mayor of Istanbul.

And he was really good at it!

The leftists were not a hard act to follow, and Erdogan was a competent and energetic administrator. Even his opponents had to admit that, under his leadership, Istanbul’s residents saw the quality of basic services improve. Residents saw new amenities under Erdogan, such as new hospitals and schools, and the expansion of the city’s bus system. Judas trees, native to Istanbul, emerged again along the city’s boulevards with their signature deep pink blossoms. His administration visibly improved Istanbul’s smog problem by expanding the city’s natural-gas distribution system as a replacement for dirty coal-burning heaters. He replaced the leftist political appointees with a team of respected academics and technicians who completed several important water-treatment projects begun under Sozen and his other predecessors. In 1994, less than 15% of Istanbul residents had access to waste-water treatment; by 1998, this figure had climbed to roughly 65%

On the strength of the same trends playing out nationally, Erdogan’s mentor Erbakan was elected as Prime Minister of Turkey. He was…not as good at it. He made some major policy missteps, and his Islamist party started getting more aggressive about hijabs and other cultural issues in ways that freaked people out. The military and their secular pro-western allies decided that maybe using the Islamists as a bulwark against Communism was a devil’s bargain, and decided to go back to their old ways. And so:

The military took matters into their own hands: the [Turkish Armed Forces] sent a contingent of 20 tanks and 15 armored vehicles through Sincan as a symbolic warning against the RP-led borough government. Deputy chief of general staff Cevik Bir characterized this as an act of “recalbrating” democracy. The rolling of tanks through Sincan would trigger a set of events, later dubbed the “soft coup”, which culminated in the RP’s fall from power.

Though the government protested these threats from the military, a week later tens of thousands of women in Ankara held a demonstration against Islamists called the “Women’s March Against Sharia”, aligning many civil-society groups and opposition leaders with the secular military. As tensions between the TAF and the government continued to escalate, on February 28 [1997] the military-dominated Turkish National Security Council held a meeting to discuss the issue of “reactionism”, a code word for Islamism since the late days of the Ottoman Empire. Following the meeting, they issued a list of 18 policy recommendations, making it clear that failure to comply would result in serious sanctions. One of the most important “recommendations” was the imposition of eight years’ mandatory secular schooling, which would force the closure of Imam Hatip middle schools. […]

Other secular forces began mounting so much pressure on the RP that the party’s power started to unravel. Eventually, faced with growing demonstrations by secular NGOs, fierce criticism from the media, rebukes from many members of the Turkish Industry and Business Association (Turkey’s club of Fortune 500 billionaires) and last but not least the looming threat of a military coup, the RP reliquished power and the RP-DYP government was dissolved on June 18, 1997.

Washington acquiesed in the “soft coup”, if tacitly. US secretary of state Madeleine Albright explained on July 11, 1997 that while military intervention was not necessarily “a silver bullet” to Turkey’s problems, the US had “made very clear that it is essential that Turkey continue in a secular, democratic way.” The EU also put its tacit blessings behind the coup, saying that while it was “concerned at the implications for democratic pluralism and freedom of expression,” “this decision [the coup] is in accordance with the provisions of the Turkish Constitution”.

Under pressure from the military, the courts banned the now-powerless RP as a “focal point for acts against the secular republic”. Erdogan scraped through by quitting the RP and founding the Totally Honestly Not An Islamic Party (FP); he was briefly allowed to remain Mayor of Istanbul. But when the courts and military finished cleaning up after the RP, they went after Erdogan’s new bloc too. The FP was shut down, and Erdogan was personally banned from politics for the crime of “reading an incendiary poem”. The Islamists appealed to the European Court of Human Rights - located in Strasbourg, France, home of laicite and enforced secularism, which ruled that none of this seemed like a human rights violation to them. Erdogan was out.

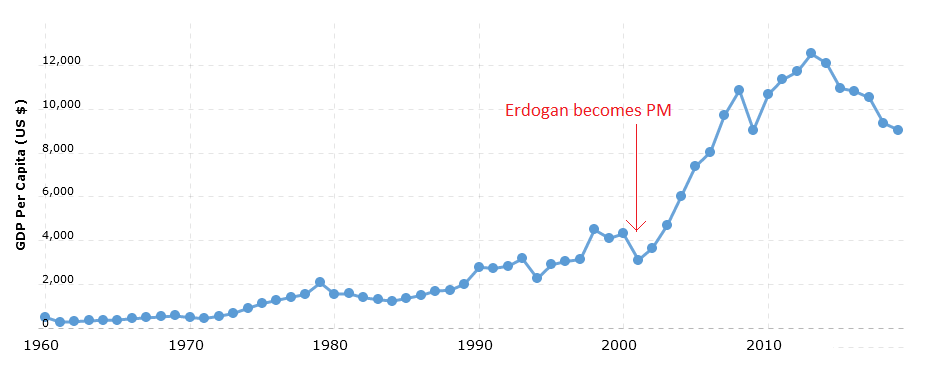

So he waited a couple of years until his ban expired, then founded the No, Really, Totally Not Islamist At All, Trust Us This Time Party (AKP). The AKP was officially center-right. It was liberal capitalist, pro-West, pro-human-rights, and big on joining the EU - all things that gave it apparently unimpeachable non-Islamist credentials. Lots of actual center-rightists joined up, noticing that Erdogan was a better leader than any of the clowns in the Turkish center-right up to that point. “Ak” is Turkish for “white”, so the AK Party was also the White Party, ie the party of being clean and pure and uncorrupt, a popular message in 90s Turkey. They won elections in a landslide, and Erdogan became Prime Minister.

III.

After one of its coups, the military made a law that only parties with at least 10% of votes could get seats in Parliament - the better to keep out small parties that the military might not be able to control. One unexpected consequence was to translate small victories into large victories, and large victories into colossal ones - many small parties would simply not make it to Parliament, and the remaining seats would be distributed among the larger winners. Something like this happened in 2002 - even though Erdogan got only 33% of the vote, he ended up with 67% of the seats in Parliament.

Erdogan had been traumatized by the 1997 military coup. He knew that if he let a hint of his true colors show, the military would depose him in an instant. So he waited, continuing to pretend to be a boring center-right liberal. “What would a real center-right liberal do?” he asked himself, and figured he might as well deregulate some stuff and pass capitalist policies. The Turkish economy entered an unprecedented boom, and a (presumably baffled) Erdogan was hailed as a genius.

“What would a real center-right liberal do?” Erdogan asked himself again, and talked to Brussels about accelerating Turkey’s EU bid. The EU said that Turkey needed to reduce the military’s role in civilian government and maybe put some measures in place to have fewer coups. “All according to plan”, Erdogan presumably muttered, rubbing his hands together gleefully, and proposed measures to limit the power of the Turkish Armed Forces. The military wasn’t thrilled about this. But Erdogan had a 2/3 majority in Parliament, and was riding a wave of popular adulation after causing an unprecedented massive economic boom, and everyone in Turkey really wanted to join the EU and would never forgive the military for holding it up, and Erdogan seemed like such a good center-rightist liberal who had learned his lesson about the whole Islamism thing. The military grudgingly agreed to let their power be curtailed.

In the end, Erdogan ends up not joining the EU. Partly this was due to a European Court of Human Rights case where the EU upheld Turkey’s headscarf ban, causing him to lose faith in the European conception of liberalism as relevant to his pro-Islam project. Partly it was the fault of the Europeans themselves, who were unsure they even wanted Turkey. The author quotes an old Turkish joke:

The EU becomes sick and tired of the arduous talks, and calls in candidate countries Serbia, Montenegro, and Turkey for a test on European history. The EU tells the three countries they will be asked one question. If they know the answer, they can join the EU, otherwise they will be rejected. The Serbs are offered the question “When did World War I begin”. This is an easy question. “The answer is 1914.” The doors open, bells ring, and Serbia joins the EU. Then the Montenegrins are asked “When did World War I end?” This, too is an easy question. “The answer is 1918.” Doors open, bells ring, and Montenegro joins the EU. Finally, the Turks are asked: “How many people died in World War I, and what are their names?”

After more and more humiliating demands, Erdogan said “f@#k it”, with the support of the Turkish people. He’d gotten everything he wanted out of the EU, but in the end Europeanism just wasn’t cutting it for him.

IV.

The Turkish word for “deep state” is derin devlet. Americans only recently became interested in the Deep State; Turks have a longer history of concern.

In 1996, Turkish police investigated a car crash. Inside the offending car, they found:

1. The deputy police chief of Istanbul

2. A notorious mafia leader with ties to the Grey Wolves militia group

3. A member of Parliament

4. A beauty queen

5. A fake passport linked to the man who tried to assassinate Pope John Paul II

6. “Numerous” guns, including two submachine guns

7. Drugs

8. Several thousand US dollars

This was a remarkable set of people and things to find in the same car! I can’t quite follow all of the threads of what later became known as the Susurluk scandal, but they apparently involved drug smuggling, terrorism, human rights abuses, several assassinations, Iranian spies, a coup against the government of Azerbaijan, and “a number of Susurluk investigators [dying] in suspicious car accidents curiously similar to the Susurluk car crash itself”.

Anyhow, this led to people thinking maybe something suspicious was going on in Turkey. The resulting Deep State conspiracy theories ranged from the obviously true (Turkish elites all knew each other and hobnobbed with each other and had lots of informal connections) to the wildly unbelievable (the Black Hand guerilla organization responsible for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand had survived World War I and had been puppeteering Turkey all along).

In 2007, a 17 year old Turkish nationalist killed a prominent Armenian activist. The government sent him to jail, but the jail term felt short to a lot of people, and “chummy photographs of policemen posing with the assassin while the latter held up a Turkish flag leaked to the public”. The old fear of sinister conspiracies started to seem more relevant.

And speaking of sinister conspiracies - a charismatic imam named Fethullah Gulen had founded a perfectly legitimate above-board network of high-quality schools around the world. After the anti-Islam coup of 1997, he fled to the US as a refugee and continued to run his school network, including schools “in 180 countries”, “160 charter schools in the US”, almost all the cram schools in Turkey, and “strong networks in Africa and the Balkans, where the highest-quality schools are often Gulenist and educate the children of the political elite”. Also various US-based lobbying groups. And a lot of Turkish organizations wielding soft power. And the Atlantic Institute, the the Pacifica Institute, and the Niagara Foundation, and the Institute for Interfaith Dialogue, and various other Institutes and Foundations and think tanks, more than you would think any normal person would need. And a weird number of graduates of Gulen schools seemed to grow up to get high positions in the militaries and judiciaries of a surprising number of countries with unknown sources of funding. All totally above-board.

In 2007, Erdogan’s worst nightmare came true. After the AKP nominated observant Muslim Abdullah Gul as President, the military decided it had enough and “issued an online press release [which] reiterated its role as the guardian of secularism and threatened “certain groups” who were working to undercut Turkey’s secular principles”. In the subtle language of Turkish politics, this was effectively a military coup - the military was saying “step down now before we take you down”. Erdogan called their bluff. He gambled everything on a hope that with the military weakened after the pro-EU reforms, and the great economy keeping his approval rating sky-high, nobody wanted to start a hot war. At least temporarily, he won his bet. “The military failed to take any further action in blocking Erdogan or Gul’s nomination, and Erdogan was able to present the armed forces, traditionally considered the most powerful institution in the country, as a paper tiger.”

But at this point Erdogan felt like he was living on borrowed time, so he decided to move against the military. He struck an alliance with the Gulenists, who despite being a totally above-board network of friendly people running nice schools happened to have seized all the most important posts in the judiciary. Erdogan got - realistically probably forged - documents proving a spectacular Deep State conspiracy called Ergenekon, a sinister organization plotting against the democratic government of Turkey. Coincidentally, it happened to include all of Erdogan’s enemies. The military, the media, the super-rich - Erdogan brought them to court one by one on forged evidence, and the Gulenist-controlled courts played along.

So did, more or less, the populace. Lots of people already suspected Deep State conspiracies. And also, the military had openly threatened to stage a coup, so the idea that many of its leaders were plotting against the Turkish government was not exactly far-fetched. Liberals who supported the rule of law were torn between Erdogan (violating the rule of law by using show trials to arrest his enemies), and the anti-Erdogan forces (probably plotting a coup, suppressing the AKP which had a strong democratic mandate) - and decided to mostly sit this one out. The media objected a bit, but Erdogan “discovered” that some of the journalists who objected were actually members of Ergenekon, and other newspapers supported Erdogan - these later turned out to be entirely owned and run by Gulenists, who sure did get their fingers in a lot of pots for an innocent above-ground network of educational institutions. In just a few years, Erdogan decimated the ranks of the military, the courts, and the media, and replaced their former leaders with a new generation of faithful Turkish patriots - all of whom were coincidentally graduates of the same friendly legitimate school network.

This was before Turkey’s EU bid died off, and Erdogan chose this moment to “liberalize” Turkish institutions. He proposed a series of amendments which would bring the Turkish government more in line with international best practices. Although these looked good on paper, the end result was to destroy previous Turkish institutions with strong traditions and independent power bases, and replace them with new ones that Erdogan could pack with his supporters. These referenda passed with strong support from Erdogan’s new coalition - center-rightists hoping that his center-right persona was the real deal, Islamists hoping it wasn’t, Europhiles impressed with the idea of rationalizing institutions and getting them to match European norms, ordinary people excited by the booming economy, and Gulenists supporting him for unclear and probably sinister reasons. Erdogan got his amendments, proceeded to clean up the last few scraps of resistance by threatening to prosecute media figures and billionaires for corruption until they gave up their newspapers/businesses to AKP supporters or Gulenists, and proceeded to become the Islamist dictator he had always wanted to be.

All dictators have to build at least one giant monument to showcase their power, and Erdogan’s was the Camlica Mosque, seen here.

All dictators have to build at least one giant monument to showcase their power, and Erdogan’s was the Camlica Mosque, seen here.

…also this classy and not-at-all-sinister-looking giant palace.

…also this classy and not-at-all-sinister-looking giant palace.

There’s more to this story. There were some anti-Erdogan protests, with various degrees of success. The Kurds have their own part in this story, which I’ve excluded to make more room for everyone else (much as Erdogan did to the actual Kurds). There may have been some foreign policy at some point. Starting around 2012, Erdogan and the Gulenists both simultaneously tried to backstab each other, a conflict which Erdogan won partly by making Turkish universities change to a “well-rounded” admissions policy that ignored exam scores - instantly destroying the cram school industry that served as the Gulen movement’s power base. There was a 2016 attempted military coup which very nearly succeeded in killing Erdogan, but which screwed up at the last second and only turned him more paranoid (he blames the Gulenists, which based on the little I know from this book seems plausible).

But the overall arc remains the same: Turkey went from somewhat-democratic-with-an-asterisk to somewhat-less-democratic-with-a-different-asterisk. On Freedom House’s measure of press unfreedom (where 0 is best and 100 is worse), Turkey went from 58 to 71 during the Erdogan years. On a political unfreedom score from 0 to 40, it went from 23 to 30. Turkish presidents are allowed to sue citizens who insult them; Erdogan’s predecessor+2 did this 26 times, his immediate predecessor 139 times, and Erdogan himself 1800 times. These kinds of numbers aren’t perfect, but enough of them have followed the same trajectory to confirm the narrative that Turkey is undergoing some bad times.

V.

So, again, can it happen here?

It seems arrogant and foolhardy to ever answer a decisive “no”, but I’m more optimistic than when I started this book. It won’t happen here in the exact way it happened in Turkey.

At the risk of being overly sympathetic to a genuinely bad guy, Erdogan became a dictator partly out of self-defense. He worried that if he tried to keep going as a democratic leader, he’d be deposed by military coup. Given that he suffered three coups / attempted coups during his career, that was a legitimate fear. And it inspired him to become powerful enough that nobody could hurt him - ie a dictator.

It also lubricated his path to power. At every step, he got support from people who were tired of the military unfairly controlling everything. Liberals who in other countries might have resisted his rise judged him the lesser of two evils, or even the underdog, and held off. Muslims, including the Gulenists, understood his ascendancy as their only route to fair political representation.

Erdogan’s struggle wasn’t just with the military. It was with NGOs, civil society groups, the wealthy, the media, etc. But to Erdogan, all these groups were useful idiots of the military, or aligned with them. Remember the sequence of events in the 1997 coup that temporarily forced Erdogan from power, quoted above:

The [Turkish Armed Forces] sent a contingent of 20 tanks and 15 armored vehicles through Sincan as a symbolic warning against the RP-led borough government. Deputy chief of general staff Cevik Bir characterized this as an act of “recalbrating” democracy. The rolling of tanks through Sincan would trigger a set of events, later dubbed the “soft coup”, which culminated in the RP’s fall from power. Though the government protested these threats from the military, a week later tens of thousands of women in Ankara held a demonstration against Islamists called the “Women’s March Against Sharia”, aligning many civil-society groups and opposition leaders with the secular military…Other secular forces began mounting so much pressure on the RP that the party’s power started to unravel. Eventually, faced with growing demonstrations by secular NGOs, fierce criticism from the media, rebukes from many members of the Turkish Industry and Business Association (Turkey’s club of Fortune 500 billionaires) and last but not least the looming threat of a military coup, the RP reliquished power and the RP-DYP government was dissolved on June 18, 1997.

For Erdogan, civil society groups gave the military the optics/PR ground support that it needed to justify its coups; the two corners of society were working hand-in-hand. He and his allies felt like they were legitimate targets, and they had a strong enough argument that the electorate didn’t hold his persecutions against him. A country without the same history of military coups, where every group feels like it’s gotten a fair shake from the democratic process, would have a lot easier time noticing and calling out illiberal behavior without having to wonder if maybe it was partially justified.

The other big difference between us and Turkey is the EU. Whatever its good intentions, the EU gave Erdogan an excuse to pave over Turkish institutions - he could credibly argue he wasn’t trying to reshape them in his own image, just modernize them as part of Turkey’s EU bid. He pulled this card again and again, and it always worked.

The third big difference is that it’s really hard to change the US Constitution. Erdogan was able to change the Turkish Constitution with a simple majority. Nobody took it too seriously, because the Constitution was just whatever the last group of military-coup-pulling generals said it was. The US Constitution requires a lot more work. And as the work of titans like George Washington and James Madison and so on, it has an aura of sacredness that makes it hard to add “PS: I can do whatever I want” to the end without a lot of people feeling violated. I know this has caused a lot of problems, but after seeing the ease with which Erdogan swept aside any part of the Turkish Constitution he didn’t like, I have a new respect for it.

But there were a few other parts of Erdogan’s rise that did seem to contain useful lessons for the US or any other country trying to preserve its democracy.

First, I was struck by how carefully Erdogan preserved the apparent structure of Turkish government and society. His style of dictatorship is less about smashing democratic institutions with a sledgehammer, and more about hollowing them out from the inside until they’re zombies following his commands while still maintaining a facade of legitimacy. If Erdogan wants your head, he’ll have a corruption investigator arrest you, bring you to court, charge you with plausible-sounding corruption allegations, give you a trial by jury that seems to observe the proper formalities, and sentence you to death by decapitation. To an outside observer, it will look a lot like how genuine corruption trials work in genuinely democratic nations. You’d have to be really well-informed to spot the irregularities - and the media sources that should be informing you all seem very helpful and educational but are all secretly zombies controlled by Erdogan supporters.

This has made me a lot less optimistic about the kind of dictator-prevention strategy where everyone has lots of guns and then if a dictator comes to power you rush out into the streets shouting FREEEEEDOM!, William-Wallace-style, shooting everything in sight. If there’s a military coup or something, this might work. But if every day your institutions are just a tiny bit less legitimate than the day before, when do you rush out into the street? One of the most important steps on the way to Erdogan’s total control was his court-packing, accomplished under the guise of EU-bid modernization. But if the Democrats manage to pack the Supreme Court at some point, are the people with guns going to rush out into the street shouting FREEEEEDOM? No - realistically even the people who really hate the Democrats and think they’re bad and wrong are going to stop short of armed revolution, because that alone isn’t quite Stalin-level obvious evil. Erdogan demonstrates that you can become a dictator through a few dozen things like that chained together, without any obvious single point where everyone wakes up and notices. There is no fire alarm for dictatorship.

Second, if there was a single moment went things obviously took a turn for the worse in Turkey, it was the Ergenekon trials - Erdogan’s attempt to forge evidence of an anti-Turkey conspiracy involving all of his enemies. This makes me a little more concerned about things like QAnon than I had been previously - if Trump had arrested various prominent Democrats for their role in a Deep State pedophile ring, that would be pretty similar to the tactic Erdogan used to seize ultimate power. On the other hand, the thing where Democrats talk about how Trump supporters entering the Capitol was an “attempted coup” and we need lots of “domestic terror laws” and a grand attempt to uncover the complicity of the mainstream Republican establishment and bring them to justice - that also feels a little too Erdoganesqe for comfort. Having ideas about the Deep State and attempted coups floating around, sounding vaguely credible, was a major factor in Erdogan’s success. The more skeptical we can be of that sort of thing, the better.

But even quashing conspiracy theories isn’t enough. When Erdogan wasn’t spinning wild stories about vast treasonous conspiracies, he got his opponents on smaller things. Ordinary bribe-taking style corruption, admittedly totally endemic in Turkey, such that any given allegation was completely plausible, becoming suspicious only because of the consistency with which people standing in Erdogan’s way got accused. Businessmen and tycoons who Erdogan needed swept aside got accused of tax fraud, or sometimes just audited with such a fine-toothed comb that they agreed to what Erdogan wanted knowing it would get the audit called off. Maybe it’s easy to instantly dismiss wild treason accusations; what about corruption and tax evasion? Don’t we want to punish those crimes? I think Erdogan’s story has me sufficiently spooked that I wonder if we should trade off our ability to catch corrupt officials and tax evaders, in favor of very high burdens of proof for those specific misdeeds. “Anti corruption campaign” seems to be a code word for “arresting the enemies of people in power”, whether in Erdogan’s Turkey or Xi’s China. I’m not sure what to do about it without leaving corruption in place, but, uh, maybe we should leave corruption in place. Hard to say.

If you asked me for my top three recommendations for shoring up American democracy against Erdogan’s particular playbook, I think at this point they would be something like:

1. Constitutional amendment against court packing (to be fair, this has been on my mind a lot recently and may not be entirely coming from the Erdogan book)

2. Stronger protections separating investigation of tax fraud (IRS?) and corruption (FBI?) from the executive.

3. More things that might be used to hack the checks-and-balances system requiring 2/3 majorities instead of simple majorities.

VI.

Erdogan gets described as a “right-wing populist”, a term I’ve always had trouble understanding.

What does it mean to condemn a party in a democracy for being “populist”? Isn’t that the whole point of democracy? Isn’t any party that wins necessarily going to be populist? Isn’t a non-populist party winning a sign something went wrong?

Second, is “right-wing populist” an arbitrary adjective-noun combination like “green-eyed populist” or “tall populist” would be? Or is there some necessary link between populism and the right wing? Aren’t leftists supposed to be the one more interested in people power and fighting “the man”? Why isn’t that populism?

Sometimes these things are easier to understand when you look at them with fresh eyes, and I found some of these issues made more sense in the context of Turkey than more locally. In the Turkish context, right-wing populism is clearly about culture-based class.

All the stuff about liberal cosmopolitan secular Europeanized Turks sipping cocktails in Nisintasi hotels sounded like the upper class. And all the stuff about poor honest nationalist Anatolian Muslim Turks from the Black Sea coastal regions sounded a lot like the lower class. Erdogan, like Trump and other figures accused of right-wing populism, claimed to be standing up for the cultural lower class against the cultural upper class.

(economic class didn’t seem like so much of a factor; Erdogan went after a lot of rich people as a threat to his power, but he also picked up a lot of rich supporters during his center-right capitalist phase)

In the course of normal politics, culture, or almost anything else, the elites will always end out on top. This flirts with tautology - of course whoever ends up on top will be a member of the elite! - but on a deeper level it isn’t - the populace and elites are different social classes and cultures, so this claim identifies a particular class/culture that always gets its way. The American equivalent might be pointing out that the winner of the Academy Awards is probably going to be from a coastal liberal secular background, and not an evangelical Protestant from Nebraska. Same for the Dean of Harvard, the editor of the New York Times, etc.

The populace can try to protest this, but their efforts are doomed to failure. Maybe they can make their own movies (eg. The Passion Of The Christ), but for whatever reason these will never be as convincing or have the same sort of clout that the elite version does. Elites have enough advantages in power, connections, education, and maybe even genes (cf. the meritocracy debate) that in the natural course of events, they always come out on top. Trying to come up with a system where elites don’t come out on top is an almost futile task, one where you will constantly be pumping against entropy.

The normal course of politics is various coalitions of elites and populace, each drawing from their own power bases. A normal political party, like a normal anything else, has elite leaders, analysts, propagandists, and managers, plus populace foot soldiers. Then there’s an election, and sometimes our elites get in, and sometimes your elites get in, but getting a political party that’s against the elites is really hard and usually the sort of thing that gets claimed rather than accomplished, because elites naturally rise to the top of everything.

But sometimes political parties can run on an explicitly anti-elite platform. In theory this sounds good - nobody wants to be elitist. In practice, this gets really nasty quickly. Democracy is a pure numbers game, so it’s hard for the elites to control - the populace can genuinely seize the reins of a democracy if it really wants. But if that happens, the government will be arrayed against every other institution in the nation. Elites naturally rise to the top of everything - media, academia, culture - so all of those institutions will hate the new government and be hated by it in turn. Since all natural organic processes favor elites, if the government wants to win, it will have to destroy everything natural and organic - for example, shut down the regular media and replace it with a government-controlled media run by its supporters.

When elites use the government to promote elite culture, this usually looks like giving grants to the most promising up-and-coming artists recommended by the art schools themselves, and having the local art critics praise their taste and acumen. When the populace uses the government to promote popular culture against elite culture, this usually looks like some hamfisted attempt to designate some kind of “official” style based on what popular stereotypes think is “real art from back in the day when art was good”, which every art school and art critic attacks as clueless Philistinism. Every artist in the country will make groundbreaking exciting new art criticizing the government’s poor judgment, while the government desperately looks for a few technicians willing to take their money and make, I don’t know, pretty landscape paintings or big neoclassical buildings.

The important point is that elite government can govern with a light touch, because everything naturally tends towards what they want and they just need to shepherd it along. But popular/anti-elite government has a strong tendency toward dictatorship, because it won’t get what it wants without crushing every normal organic process. Thus the stereotype of the “right-wing strongman”, who gets busy with the crushing.

So the idea of “right-wing populism” might invoke this general concept of somebody who, because they have made themselves the champion of the populace against the elites, will probably end up incentivized to crush all the organic processes of civil society, and yoke culture and academia to the will of government in a heavy-handed manner.

In this model, left-wing populism would be someone trying the same thing, except using economic rather than cultural class war. I don’t know enough about this to have a good feeling for whether it has exactly the same pathologies or subtly different ones. “Take government control of industries” is a simpler task than “take government control of art and academia”, but I’m not sure if that makes things better or worse.

I previously suspected that “right-wing populism” was a little too convenient a label, one invented by lefties who wanted to claim that their philosophy can’t possibly go wrong, nosirree. I think that was unfair. Leftist philosophy can go wrong. But the coiners of the term “right-wing populism” were correct in pointing out the ways that right-wing movements are more likely to tend towards certain kinds of dictatorship. Erdogan offers a stark case study in how it happens, but there are too many Turkey-specific points for me to feel comfortable drawing general conclusions.