Book Review: The Origins Of Woke

The Origins Of . . . Civil Rights Law

The Origins Of Woke , by Richard Hanania, has an ambitious thesis. And it argues for an ambitious thesis. But the thesis it has isn’t the one it argues for.

The claimed thesis is “the cultural package of wokeness is downstream of civil rights law”. It goes pretty hard on this. For example, there’s the title, The Origins Of Woke. Or the Amazon blurb: “The roots of the culture lie not in the culture itself, but laws and regulations enacted decades ago”. Or the banner ad:

The other thesis, the one it actually argues for, is “US civil rights law is bad”. On its own, this is a fine thesis. A book called Civil Rights Law Is Bad would - okay, I admit that despite being a professional Internet writer I have no idea how the culture works anymore, or whether being outrageous is good or bad for sales these days. We’ll never know, because Richard chose to wrap his argument in a few pages on how maybe this is the origin of woke or something. Still, the book is on why civil rights law is bad.

Modern civil rights law is bad (he begins) for reasons baked into its history. The original Civil Rights Act of 1964 was supposed to be an ad hoc response to the outrageous level of anti-black racism going on in the South, which protests and TV news had finally brought to the attention of the white majority. There was broad support for a bill which was basically “don’t be the KKK”.

Sex discrimination got tacked on half as a joke, half as a poison pill by its enemies to make the bill unpalatable (fact check: true - but there’s a deeper story, see this Slate article for more details). Ideas about “affirmative action” and “disparate impact” weren’t tacked on at all; the bill’s proponents denied that it could be used to justify anything of the sort, and even agreed to include language in the bill saying it was against that. Still, after the bill was passed, a series of executive orders, judicial decisions, and bureaucratic power grabs put all those things in place.

The key point here is that “quotas”, or any kind of “positive discrimination” where minorities got favored over more-qualified whites, were anathema to lawmakers and the American people. But civil rights activists, the courts, and the bureaucracy really wanted those things. So civil rights law became a giant kludge that effectively created quotas and positive discrimination while maintaining plausible deniability. This ended up as the worst of both worlds. Hanania specifically complains about1:

Affirmative Action

Hanania’s take on affirmative action involves the government sending companies a message like this:

-

We notice your workforce has fewer minorities than the applicant pool.

-

If this remains true, we’ll sue you for millions of dollars and destroy your company. So by the next time we check, your workforce had better have exactly many minorities as the applicant pool.

-

But you’re not allowed to explicitly favor minority applicants over whites. You certainly can’t do anything flagrant, like set a quota of minority employees equal to their level in the applicant pool.

-

Have fun!

(here “the applicant pool” is an abstraction, often but not always the same as the general population, which is poorly defined and which bureaucracies can interpret however they want. It’s definitely not the same thing as the actual set of qualified applicants to the business!)

This satisfied the not-really-paying attention white electorate, because politicians could tell them that “quotas are illegal, we’re sure not doing anything like that”. And it satisfied civil rights activists, because inevitably businesses/departments came up with secret ways to favor minorities until representation reached the level where they wouldn’t get sued.

A recent case illustrates the results of this double-bind. The FAA hires air traffic controllers. They used to judge applicants based on a test which measured their skills at air traffic control. This resulted in comparatively few black air traffic controllers. Various civil rights groups put pressure on them, and they replaced the test with a “biographical questionnaire”. The questionnaire asked weird unrelated questions about your life, and you got points if you gave the answer that the FAA thought black people might give (for example, if you said your worst subject was science). This still didn’t get them enough black employees, so they secretly told black communities exactly what answers to put on the questionnaire to go through.

It’s easy to blame the FAA here, but (Hanania says) civil rights law almost forces you to do something like this. People tried simpler things, like keeping a test but giving minority applicants extra points. The courts and civil rights bureaucracy struck these down as illegal. The almost-explicit policy was that you had to get more minority employees, but you had to hide it carefully enough that the American people (who were still against racial preferences) wouldn’t catch on.

Disparate Impact

Not only can you not explicitly discriminate, you can’t use hiring criteria that “accidentally” discriminate by favoring one race over another. To give a stupid example, if someone refused to hire anyone from Detroit, this would have “disparate impact” since Detroit is a majority black city. If you allowed stuff like this, racists could covertly discriminate by using these sorts of rules.

But Hanania challenges us to think of any criterion that isn’t potentially racially biased. For example, we know universities discriminate against Asians, so only hiring people with college degrees is a “disparate impact”. We know that more men than women have experience as miners, so a mining company only hiring employees with experience is a “disparate impact”. Since whites typically do better on IQ tests than blacks, and all cognitive skills are correlated with IQ, the Supreme Court decided in Duke vs. Griggs that all tests of any ability were potentially disparate impact, and you opened yourself to lawsuits if you used any of them.

(in theory, companies are allowed to use tests and similar criteria if they prove them nondiscriminatory. But the standards for this - they have to prove it for each race and each job site individually - are so high that, in practice, few companies take this route.)

Since this technically banned all possible criteria, companies couldn’t follow the letter of the law. Instead they hired fancy lawyers to tell them which way the winds were blowing. The lawyers told them that college degrees were okay, resumes with biographies and experience were maybe okay, and interviews were okay. Tests were out. Anything more creative was out.

A disparate impact case made the news recently. The Biden EEOC sued convenience store chain Sheetz for running criminal background checks on their employees. They didn’t allege any intentional discrimination. They just said that more minorities fail criminal background checks than whites, therefore it’s disparate impact, therefore Sheetz has to drop the criminal background check.

(the article links to another famous case, where the Obama EEOC sued a corporate events planner, demanding they give monetary compensation to an employee who they had refused to hire simply because he had committed attempted murder and lied about it on their job application)

Is Sheetz the only company that does criminal background checks on its employees? Do they do the background checks differently than any other company? My understanding is that the technical answer is that to do background checks without being sued, you have to prove in some very formal way that the specific crimes you’re looking for would be bad for your specific industry, and maybe Sheetz didn’t prove that a general history of violence was bad for convenience stores. But if this sounds kind of fake to you, and you’re wondering whether the real rule is “the government has wide discretion to prosecute whoever it feels like”, Hanania’s answer is “definitely yes”.

His position is that all of these rules are so broad that every company is always violating them in some sense. No company has exactly the same distribution of minorities as “the applicant pool”, whatever that is. No company has some magical hiring rule that has literally zero correlation with race, especially since black people are poorer, less educated, and less likely to have any given achievement (so any attempt to choose better employees over worse will necessarily disadvantage them). In real life, the bureaucracy’s rules are something like “don’t do anything different from other companies in your industry, and especially don’t be caught seeming less woke”. Hanania argues this creates an arms race / ratchet. Every company wants to be at least 50th percentile wokeness or above. But not every company can be above average. So everybody gets more and more woke, with no end in site.

Continuing with Sheetz: according to the article on the lawsuit, in 2020 they “introduced the IDEA initiative”, ie Inclusion Diversity Equality & Accessibility. Their website has a big picture of a black woman saying “We’re Building A Great Place To Work For All”, and boasts that they’ve created a special forum for black employees. They’ve made 60% of managers women, started a Woman’s Leadership Program, offered generous maternity leave, and written letters to the Chamber of Commerce on how the George Floyd murder made them realize “we quickly needed to learn, listen, be vulnerable and humbly approach . . . culture-shifting work”. Companies hope that if they do enough of this stuff, the EEOC will agree they’re an ally in the civil rights project and not sue them under their wide discretion to sue basically anyone. Too bad they’re getting sued anyway; some other convenience store must have done more of this stuff. Surely some executive is wishing they had just tried having one more mandatory diversity training…

Harassment Law

Harassment law might win the award for most complicated chain of reasoning from real legislation to enforcement:

-

Legislation says you can’t discriminate against minorities

-

If you bully minorities out of your company, that would be a way to discriminate against them.

-

So you can’t have an environment that’s so hostile to minorities that they inevitably leave.

-

In some sense, anything that offends a minority is part of this environment.

-

Any joke, political comment, flirtation, etc, could potentially offend a minority.

-

Therefore, every business owner needs to monitor their employees for jokes, political comments, flirtatiousness, and take action against any offenses.

Hanania has several complaints here. First and most legibly, it (say it with me) gets taken too far.

Volokh lists a large number of [examples of things that have been found to be] evidence of a hostile work environment: signs with the phrase “men working”; “draftsman” and “foreman” as job titles, pictures of Ayatollah Khomeini and a burning American flag in a cubicle; an ad campaign using samurai, kabuki, and sumo wrestling to refer to Japanese competition; jokes of a sexual nature not targeted at any particular person; misogynistic rap music […] even terms like “great view” and “walk-up” have been cited as potentially trying to exclude blind people and those in wheelchairs.

And

In a 2015 and 2016, a black father and son named Owen Diaz and Demetric Di-az [sic] worked at a Tesla plant. They sued the company for racial discrimination, with the father’s claims alone making it to trial….racial slurs were used in the presence of Diaz, and he saw racist graffiti on a bathroom wall. It appears that the workers allegedly responsible were mostly or all minorities themselves, and each time an allegation could be verified, the employee was punished. Tesla claimed that they had taken enough steps to address the concerns of Diaz […] a jury disagreed, and awarded the plaintiff $137 million, an amount that the judge reduced to $15 million. In response to the verdict, Tesla released a statement pointing out that witnesses confirmed that the slurs were used in a friendly manner, usually by African-American employees, and without hostile intent.

(fact check: this article says the racism also included demands to “go back to Africa” people leaving drawings of caricatured black cavemen at the employee’s desk, threats, and claims that black employees were “given the most menial and physically demanding work”, and that they were backed up by testimony from two dozen former workers and a cellphone video showing people telling a black employee that they are going to “cut you up, n—-r”. This seems like a sufficiently different story that I’d like to know whether Hanania still stands by his version)

Other parts of harassment law lead to more unfair double-binds. For example, you can’t be seen to “retaliate” against someone who accuses another worker of harassment. So suppose that a minority employee is bullying a white employee, the white employee resists, and the minority accuses them as “harassment”. Maybe there’s even a full trial, everyone agrees this is what happened, and the white employee is found totally innocent. Still, you can’t fire the bully, because that would be retaliation for a harassment complaint. And since you probably don’t want the bully and their victim in the same department, you need to move one of them. And you can’t move the bully, because that would be viewed as “retaliation” for the harassment complaint and they could sue you for millions of dollars. So you have to punish the victim.

But Hanania doesn’t just say this kind of thing goes too far. He has some broader point that I have trouble interpreting - basically that corporations used to be cozy, chummy places full of banter and flirtation that everyone enjoyed, and now this has been universally replaced with the bland soul-draining bureaucratic corporate aesthetic satirized in works like Office Space.

Is this true? People talk about Mad Men (I’ve never seen it) as reflecting some kind of corporate golden age where at least high-ranking men enjoyed their jobs. If so, did it change because of harassment law? Or because neoliberalism replaced the work-for-thirty-years-and-get-a-golden-watch corporation with the work-for-three-years-and-then-seek-a-better-job-elsewhere corporation?

Still, Hanania really hammers in this point that we should apparently all be angry about the loss of corporate flirtation - he calls the current regime, “a sexless, androgynous, and sanitized workplace” which is “contrary to human nature [and] miserable”. Without civil rights law, we could have “organizations that combined the aspects of a church, a social club, a matchmaking service, and a traditional business.”

In such a world:

Some corporations start encouraging dating and forming close personal bonds among their employees. This can take many forms, from Christian matchmaking to promoting a party-like atmosphere. These pro-relationship corporations will come in conservative or liberal forms. Other firms explicitly market themselves as providing a more “professional” or “classic” work experience . . . we will see a period of wild experimentation, with some forms of corporate organization drawing a great deal of media coverage. People will criticize many of these experiments, and they will become the subject of public outrage. After civil rights law has been defanged, however, government no longer has the ability to easily shut such efforts down. Eventually, public anger subsides, and the idea of the media attacking a firm because it dislikes its internal culture will seem as intolerant as attacking a religious community for its doctrines, or homosexuals for what they do together as consenting adults.

I appreciate my anti-civil-rights books doubling as interesting settings for pornographic stories, but I’m otherwise unable to fathom the level of Hanania’s enthusiasm here.

…And More

Richard Hanania hates all this stuff.

Partly he hates it because he thinks it’s unfair and anti-business and anti-merit. But also, Vaclav Havel talks about the indignity of life under communism. You weren’t allowed to just do your job and pay your taxes and follow the laws of the communist state. You had to be actively complicit. You had to act enthusiastic about the communism, force it upon others, inform on your colleagues and punish deviation - at least if anybody was going to check later. This kind of communism didn’t just hurt your pocketbook. It damaged your soul. It molded you into a worse and uglier type of person who would eventually abandon their better impulses in order to justify their actions to themselves.

This is how Hanania thinks of civil rights law. Business owners can’t just give blacks ten extra points on the screening test and call it a day. They have to favor blacks while insisting to everyone that they don’t do this and it’s perfectly fair and they love civil rights law. They have to twist their employment criteria into some kind of illegible monstrosity so nobody can notice all the favoritism they’re doing, then tell everybody that they believe the monstrosity is “fairer”. They have to hire a bunch of diversity coordinators - not because they’re required to hire diversity coordinators, it’s not a requirement - but because they love equality so so much (and if they don’t do this, they’ll get sued for seemingly unrelated reasons). Everyone faces a constant threat of lawsuits which can only be warded against by seeming maximally woke and maximally enthusiastic and maximally happy about all the idiotic fake laws you are being forced to comply with.

Like in communism, you have to become your own mini-police state. You have to make employees snitch on each other if they tell the wrong joke. You have to turn your company into a tyranny of HR ladies. If you do any of this even a little less than other companies, you’ll get sued for seemingly unrelated reasons, with penalties running potentially into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Because there’s no legible law except “be the same as everyone else so you don’t stand out as sue-able”, every corporation homogenizes into the same bland HR-ocracy. Everyone agrees on the same hiring process, which is to prioritize college degree, resume, and interview, and definitely not any test or measure of ability. This leads inevitably to our current society, where everyone has to waste their childhood doing meaningless extracurriculars so they can get into the best college so they can take the best internships so they get the best jobs.

(unless they do something stupid like let themselves get the dreaded “resume gap”).

But also:

During the early 1800s, government positions were given out by the “spoils system”, basically “does the party in power like you personally?” In the 1880s, after President Garfield was assassinated by a guy who didn’t get a good enough position, they switched to a formal civil service, based on test performance and merit. The US civil service became the envy of the world, attracted some of the smartest people in the country, and obviously worked better than the old system wherever it was possible to compare. Still, this gradually (and somewhat deniably) ended in the 1970s, because the merit-based hiring system seemed like disparate impact. Hanania calls the current era “the racial spoils system”, where positions in the bureaucracy are based on the same kind of illegible morass as everything else (eg the FAA’s “biographical questionnaire”). He says every branch of government has become less effective as a result.

Hanania doesn’t mention this, but I’ve heard an additional argument elsewhere. It’s very legally dangerous for companies to hire based on anything like merit. Still, if you have great lawyers and are willing to pay a lot to settle lawsuits, you can get away with legally dangerous things. This is only worth it if you really really want high-merit employees, ie if the best employee is much more financially valuable to you than the second-best. This is mostly true in Wall Street (where you want your trader to outsmart the other guy’s trader by half a millisecond or whatever) and Silicon Valley (where ten employees can write a program used by millions of people). So the government, the civil service, the schools, etc, all abandoned merit-based hiring, whereas Wall Street and Silicon Valley lawyered up. But that means that if you’re a smart non-minority college graduate, you know that joining the civil service will be a mess - you’ll have a tough time even getting in, and you’ll always be passed over for promotions for less-qualified minorities. Meantime, Wall Street and Silicon Valley would love to have you. So all the smart people got concentrated in a few industries, and the old American tradition where elite families would send some of their kids into public service died out.

What To Do?

Hanania stresses that most Americans hate affirmative action (and probably by extension most other civil rights law, though they’ve probably never heard of disparate impact). Affirmative action has been on the ballot nine times, and failed eight of those. Most recently, it failed in California, a deep-blue, 66% minority state where the pro-AA side outspent opponents 17-to-1.

Also, Republicans have controlled all the branches of government many times in the past fifty years, and now they control the Supreme Court. Most civil rights law is based on executive orders and judicial decisions, so you wouldn’t even need a Congressional vote to overturn it. Just an executive order, from any president who felt like it. Reagan could have overturned half of this with the stroke of a pen, if he’d wanted. So how has it survived this long?

His answer: because until about 2010, Republicans were too scared of getting called racist. Reagan wanted to overturn affirmative action, but other Republicans (like Bob Dole) begged him not to, because racism, and eventually he caved. But since 2010, everyone has already been calling Republicans racist all the time, to the point where probably this threat has lost its power. And the sort of moderate Republicans who reined in Reagan are gone. So why haven’t Republicans (eg Trump) acted? Hanania thinks everyone is so obsessed with “woke” culture war stuff that the low-hanging fruit of actual woke laws that presidents can change has slipped under the radar.

And so, this book. I would have summarized the case as “Hey, Republicans! Do you hate wokeness? Well, too bad, it’s a vast cultural movement with bastions in a bunch of places where we have no power. But some of this civil rights law stuff seems pretty related to wokeness, and we do potentially have power there. So instead of fighting the unwinnable cultural battle, how about we fight the very winnable policy one?”

But maybe this didn’t seem optimistic enough for Hanania, so he framed it as “the legal wokeness is the source of the cultural wokeness” instead. More on this later.

The Origins Of . . . Inequality

A progressive, reading this book, might counter: “Sure, civil rights law - like all law - is poorly written and kludgy in parts. Like all law, it sometimes gets abused or taken too far. Those are the costs. But the benefits are that it fights discrimination and inequality. That’s very important! Don’t you think those benefits are worth the cost?”

Unless I missed it, Hanania doesn’t touch this obvious counterargument. He briefly says that in a free market, companies couldn’t consistently maintain discrimination, because that would be leaving money on the ground.

“Cool theoretical result,” objects the hypothetical opponent. “But white households earn an average of $80K and black households an average of $50K, and so on with other minority groups. So it sure seems like something inequality-related is going on.”

My tongue-in-cheek reframing of Hanania’s summary of civil rights law went:

We notice your workforce is less black than the applicant pool.

If this remains true, we’ll sue you for millions of dollars and destroy your company. So by the next time we check, your workforce had better be exactly as black as the general population.

But you’re not allowed to explicitly favor black applicants over whites. You certainly can’t do anything flagrant, like set a quota of black employees equal to their level in the applicant pool.

Have fun!

Our hypothetical opponent could argue there’s nothing necessarily contradictory or Orwellian about this. If your company is whiter than its applicant pool (eg the general population2), then you must be discriminating. If you stop discriminating, you can get racial balance without any of that nasty quota stuff. So what’s the problem?

Everyone is so circumspect when talking about race that I can never figure out what anyone actually knows or believes. Still, I think most people would at least be aware of the following counterargument: suppose you’re the math department at a college. You might like to have the same percent black as the general population (13%). But far fewer than 13% (let’s say 2%) of good math PhDs are black. So it’s impossible for every math department to hire 13% black math professors unless they lower their standards or take some other drastic measure.

Okay, says our hypothetical opponent. Then that means math grad programs are discriminating against blacks. Fine, they’re the ones we should be investigating for civil rights violations.

No, say the math grad programs, fewer than 13% of our applicants are black too.

Fine, then the undergrad programs are the racists. Or if they can prove they’re not, then the high schools are racist and we should do busing. The point is, somebody somewhere along the line has to be racist, right?

I know of four common, non-exclusive answers to this question.

-

Yes, the high schools (or whatever) are racist. And if you can present a study proving that high schools aren’t racist, then it’s the elementary schools. And if you have a study there too, it’s the obstetricians, giving black mothers worse pregnancy care. If you have a study disproving that too, why are you collecting all these studies? Hey, maybe you’re the racist!

-

Maybe institutions aren’t too racist today, but there’s a lot of legacy of past racism, and that means black people are poor. And poor people have fewer opportunities and do worse in school. If you have a study showing that black people do worse even when controlled for income, then maybe it’s some other kind of capital, like educational capital or social capital. If you have studies about those too, see above.

-

Black people have a bad culture. Something something shoes and rap music, trying hard at school gets condemned as “acting white”. They should hold out for a better culture. I hear nobody’s using ancient Sumerian culture these days, maybe they can use that one.

-

White people have average IQ 100, black people have average IQ 85, this IQ difference accurately predicts the different proportions of whites and blacks in most areas, most IQ differences within race are genetic, maybe across-race ones are genetic too. I love Hitler and want to marry him.

None of these are great options, and I think most people work off some vague cloud of all of these and squirm if you try to make them get too specific. I don’t exactly blame Hanania for not taking a strong stand here. It’s just strange to assume civil rights law is bad and unnecessary without having any opinion on whether any of this is true, whether civil rights law is supposed to counterbalance it, and whether it counterbalances it a fair amount.

A cynic might notice that in February of this year, Hanania wrote Shut Up About Race And IQ. He says that the people who talk about option 4 are “wrong about fundamental questions regarding things like how people form their political opinions, what makes for successful movements, and even their own motivations.” A careful reader might notice what he doesn’t describe them as being wrong about. The rest of the piece almost-but-not-quite-explicitly clarifies his position: I read him as saying that race realism is most likely true, but you shouldn’t talk about it, because it scares people.

(I’m generally against “calling people out” for believing in race realism. I think people should be allowed to hide beliefs that they’d get punished for not hiding. I sympathize with some of these positions and place medium probability on some weak forms of them. I think Hanania is open enough about where he’s coming from that this review doesn’t count as a callout.)

His foil here is race realist Nathan Cofnas, who says you have to discuss these things. Otherwise progressives can win every argument by using the line of reasoning above - “Just look how much inequality there still is, this shows there’s still lots of racism or at least the lingering effects of past racism, obviously our job isn’t done yet and we need lots more civil rights law to combat it.”

Hanania’s answer to Cofnas is that this isn’t a debate club. “Ah, but Glaucon, your claim that affirmative action is unnecessary must imply the corollary that there must be no inequality, thus proving a contradiction.” LOL no. Realistically this will get fought on the level of “You oppose affirmative action, which makes you a gross Nazi” vs. “You support affirmative action, which makes you an annoying wokescold.” Just say the wokescold thing louder than your enemies say the Nazi thing, and you win. Talking about racial differences scares people off and doesn’t help.

I find it hard not to feel contempt for this level of contempt for reason, but Hanania is no doubt right about the strategic considerations. And in his book, he follows his own principle. There’s no discussion of why civil rights law might be necessary, or why it might be impossible for companies to hire enough minorities without reverse discrimination. As he predicts on his blog, it’s not fatal. You wouldn’t notice unless you were looking for it.

I’m not really sure what to do here. How do you review a book that has a glaring omission, but also its author has written an essay called Here’s Why I Like Glaring Omissions And Think Everyone Should Have Them? Is it dishonest? Some sort of special super-meta-honesty? How many stars do you take off? Nothing in my previous history of book-reviewing has prepared me for this question.

The Origins Of . . . Racial Categories

Hanania presents a few scattered arguments that civil rights law is the origin of woke, of which the section on racial categories was most interesting.

Having instituted affirmative action, the government had to decide what categories it was going to inspect businesses for. Like the rest of civil rights law, the resulting system was a bunch of political kludges. There is no “true” set of races that “falls out naturally” from genetic or cultural data, but the US government’s system was especially fake and embarrassing.

-

They created the concept of “Asian-American” by combining the old category “Oriental” together with Indians, Pakistanis, Thais, etc. Then, under pressure from the Hawaiian delegation, they added Pacific Islanders to create a even more heterogenous and meaningless category of “AAPI” (Asian American or Pacific Islander). Then, under more pressure from Hawaii later, they separated out “Native Hawaiian” again. The result is that Pakistanis, Koreans, and Tongans are the “same race”, but Hawaiians and Samoans are “different races”.

-

They combined Mexican-Americans, Cuban-Americans, and Puerto Ricans - previously three different groups that had been viewed as “white lite” along the same lines as Italians - into the new race “Hispanic”, adding in all of South and Central America for good measure. Then, under pressure from black activists who were worried that some blacks would reclassify as Hispanics and they’d lose constituents, they declared Hispanics to be an “ethnicity” that you could have along with a different race. So a white Spaniard from Spain and a white Spaniard from Mexico got treated as different ethnicities, but a white Spaniard from Mexico and a Mayan from Mexico got the same ethnicity.

-

Even though Arabs and Muslims are one of the most discriminated-against groups in the country, especially after 9-11, they didn’t have good lobbyists, so they got classified as white. According to Hanania, the government’s dividing line for white vs. PoC is at the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, and nobody knows what to do about eg Uzbeks. Hanania himself is Palestinian-American and seems salty about this.

All of this means that (for example) a company that had 10 Pakistanis and 10 Afghans might get classified as “too white” and get sued for failing to hire enough Asian-Americans. But a company that had 20 Pakistanis, or 10 Pakistanis + 10 Koreans, would be fine.

Hanania argues that this has gone beyond corporations and seeped into the culture, helping create modern wokeness. For example, after some Chinese people got beaten up a few years ago, there was a campaign to #StopAAPIHate, as if AAPI were a natural category, or there were some racists targeting AAPIs in particular. Does this mean government-mandated racial categories are invading our deepest thoughts?

That one campaign was kind of silly. But aside from that example, I don’t usually hear people talk about AAPIs outside a purely legal context. All my Asian (eg Chinese, Japanese, etc) friends self-identify as Asian. When Everything Everywhere All At Once came out, people said it was a movie about the “Asian” experience. The top Ivy League colleges have an Asian Student Association (Harvard), an Asian American Students Alliance (Yale), or an Asian American Students Association (Princeton), with Pacific Islanders nowhere to be seen. With all due respect, Hanania really doesn’t have much here beyond the #StopAAPIHate thing - which seemed like a weird astroturf campaign in other ways and probably shouldn’t be taken as actual grassroots racial categorization.

The point about “Hispanics” is better taken, and you can read more about the case here. But since 1964, when Mexican-Americans, Cuban-Americans, and Puerto Ricans were the three equally-sized and equally-interesting groups, the Hispanic community has become dominated by Mexican (and Central American) immigrants, who do form a pretty natural grouping. People are just as happy to talk about Latinos (and Latinx) as Hispanics. I’m not sure we can attribute this one to the government either.

As for Arabs, they seem to have plenty of organization and activism, eg CAIR; if this is less prominent than eg Asians or Latinos, it’s probably because Arabs are about 0.5% of the US population, compared to Asians’ 5% and Latinos’ 20%.

Hanania’s strongest point here, more suggested at than asserted, is that maybe civil rights law prevented Hispanics from assimilating into “white” the same way Italians and Irish did before them. Hanania claims that Mexican-American activists originally demanded to be classified as white, then turned 180 degrees after affirmative action proponents promised them better jobs for being non-white. This seems like one of the bigger what-ifs of American racial history, although people say that maybe Hispanics are assimilating somewhat anyway - the much-remarked upon rise in Hispanic white supremacists seems like a weird yet promising sign here.

The Origins Of . . . Woke

Aside from this, Hanania doesn’t have much to support his claimed thesis - that civil rights laws are upstream of the cultural package of wokeness. He mostly goes with vague, zoomed-out arguments. Civil rights law sets people against one another. It accustoms them to lying. It forces them to focus on people’s race instead of being color-blind. It denies merit. It saps people’s hope for the future, and their ability to trust the political system.

The few exceptions where he gave more specific stories were helpful. For example:

Civil rights acts as a sort of force multiplier for disgruntled employees . . . allowing them to change institutions from the inside. The same company that might not think twice about disciplining workers for making unfounded or exaggerated claims about other aspects of its business can have its hands tied if the allegations being made contain even a hint of a charge of racism or sexism. As mentioned before, civil rights law bans “retaliation” against an employee even if the underlying complaint is ultimately without merit. When Sen. Tom Cotton wrote an article in the New York Times in the summer of 2020 calling for the military to be sent to deal with rioters in major American cities, the opinion editor of the paper eventually resigned after employees waged a campaign against him that included sending out identical tweets saying that the piece put black staff in danger. Had they claimed a grievance based on some other, “non-protected” identity, there would not have been the specter of legal liability for the article, nor would the controversy have invoked the grievance procedures and norms already established to deal with racial issues.

If a major newspaper being influenced in its staffing and editorial choices by civil rights law seems too absurd to contemplate, consider that Felicia Sonmez, a reporter for the Washington Post, sued her employer on the grounds that it was discriminatory to take her off #MeToo stories after she talked about her own alleged sexual assault. Although her suit was dismissed in 2022, newspapers are no different than other employers in responding to incentives. Sonmez was eventually fired by the Washington Post in 2022 for weeks of publicly attacking coworkers on Twitter. It is reasonable to wonder whether the employer’s hesitancy to part ways with her was based on the incentives created by civil rights law and their downstream cultural effects.

So maybe the causal pathway is civil rights law → woker workforce at newspapers/universities/etc → cultural wokeness? But there’s not a lot here beyond this NYT example.

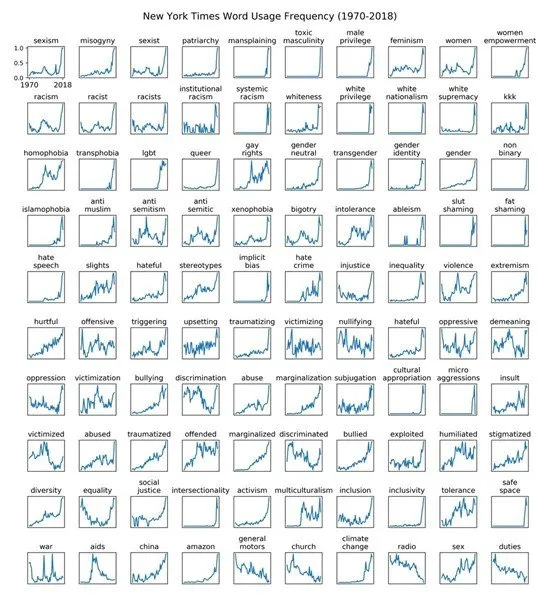

When I think of wokeness, I think of the great cultural turn around 2010 - 2015, when everybody started talking about privilege and white supremacy, Black Lives Matter burst onto the cultural scene, all your friends suddenly had rainbow and trans flags in their social media profiles, and people coined terms like “SJW” and “woke” to describe this phenomenon.

Source: David Rozado

Source: David Rozado

Hanania has no explanation for this. He talks about civil rights laws that have been in place since 1964 (he does say that maybe the new civil rights bill signed in 1991 inspired that decade’s interest in “political correctness”, but The Closing Of The American Mind, generally considered the opening shot in that debate, was published in 1987). Why would 1964 and 1991 laws turn wokeness into a huge deal in 2015? Hanania has no answer.

Even the book’s own history of the civil rights movement seems to undermine its thesis. This history, remember, is that Congress tried to pass reasonable and limited laws, and then woke activist judges and bureaucrats kept expanding them into unreasonable power grabs. And that (he says) was the origin of wokeness. But if a movement has already captured the judicial branch and the civil service, it seems like it must have already originated before then. Grant that this was an older form of wokeness more clearly grounded in the anti-segregation struggles of the 1960s. But that just brings us back to the question of where the new 2010s version of wokeness came from, which the book also doesn’t answer.

How did civil rights law cause the Ferguson riots? The George Floyd protests? Joe Biden’s promise to appoint a black female Supreme Court Justice (and his black female vice president)? Drag queen story hours? Gay pride parades? If it doesn’t explain any of those things, what’s left of it explaining “wokeness”?

How did gay, lesbian, and transgender people win their rights, normalize their identity, and win victories in representation, medical care, and even the language? When these groups were still unpopular, civil rights law didn’t apply to them. They fought their way up from zero, with little legal help, until they were powerful enough that they could lobby for civil rights protection. Transgender people in particular weren’t covered under civil rights law until 2020, and they still don’t get some of the most-sought benefits like affirmative action. But they’re a central example of wokeness. Isn’t this evidence that wokeness can thrive without support from civil rights law?

I don’t read Hanania’s blog religiously. Maybe he has an article somewhere about Here’s Why I Think It’s Good To Have A Glaring Omission Around This Part Of My Argument. But I can’t predict what it would say.

The Origins Of . . . The Next Trump Administration’s Civil Rights Policy

Like I said with What We Owe The Future , it’s probably unfair to review this book qua book.

I appreciated the readable and thoughtful overview of civil rights law and its history. I was already skeptical of affirmative action; this book further confirms that skepticism. I was less convinced by the attempt to connect it to cultural wokeness, but that’s fine - it seems to have caused enough direct damage to corporations, universities, employees, government departments, etc, to judge it negatively on those terms.

(although I’m suspending final judgment here based on my spot-check of the Tesla story turning up a different enough sequence of events that I’m not sure how much else was presented in a one-sided way - let me know if you find other parts that seem wrong.)

But my impression of Hanania’s place in the ecosystem is that he’s not writing this for you or me. He’s writing this for a group of conservative heavyweights who will set policy if Trump wins in November. He’s reminding them that civil rights law exists, that it’s against conservative principles, and that it’s pretty easy for a president to repeal large parts of it. All the rest of the book is just a booster stage to help it reach those people.

It doesn’t matter if Hanania has a coherent theory of discrimination, or a coherent theory of how civil rights law causes woke culture. His instincts here are really good. He’s written a book that’s become popular and talked about, which has attracted exactly the sorts of policy wonks he wanted, and that’s well-designed to make them to pay attention to this issue. In this sense, the book is perfect. Complaining that it doesn’t satisfy my intellectual curiosity is like complaining that the operating manual for a missile system lacks convincing characterization or plot.

Read this book if you want a well-written expose of the past fifty years of civil rights decisions. Or read it in order to feel like you were ahead of the curve if Executive Order 11246 gets repealed on January 21, 2025.

-

I’ve included three of Hanania’s four civil rights law subtopics. The book covers a fourth, Title IX (ie women’s sports in college). Although the book provides lots of examples about how the laws here are unfair and outrageous, I can’t bring myself to care about college sports enough to give it the same subtopic status, as, say, the hiring process for all the corporations in America.

-

Once again, we’re assuming that the government misuses the concept of “applicant pool” here, either by setting it equal to the general population, or else some other group that isn’t your real applicant pool, or else your applicants include some manifestly unqualified people (eg professor candidates with no PhD) who get included anyway. My impression from talking to people in hiring is that this is definitely true. But also, remember that nobody knows how the government plans to treat them or define their “applicant pool”, so just the rumor of this makes everyone live in fear.