Book Review: Why We're Polarized

I.

Ezra Klein is great. I know a lot of people throw shade on him for founding Vox. But as Van Gogh said about God creating the world, “We must not hold it against Him; only a master could make such a mistake”. Ezra is a master and I was happy to be able to read his Why We’re Polarized.

(Amazon recommended it to me as “Why We’re Polarized By Ezra Klein”, which I would also have been happy to read.)

Did you know that seventy years ago, our grandparents were having an underpolarization crisis? True! In 1950, the American Political Science Association “released a call to arms…pleading for a more polarized political system”. The report argued that “the parties contain too much diversity of opinion and work together too easily, leaving voters confused about who to vote for and why”. Everyone agreed with each other so much, and compromised so readily, that supporting one party over the other seemed almost pointless.

In 1976, three years after Roe v. Wade , Democrats and Republicans were about equally likely to support abortion restrictions. That same year, a poll found that “only 54% of the electorate believed that the Republican Party was more conservative than the Democratic Party”; 30% thought there was no difference. As late as 2004, about equal numbers (within 5 pp) of Democrats and Republicans agreed with statements like “government is almost always wasteful and inefficient” and “immigrants are a burden on our country”. Between the late 60s and early 90s, Democratic presidents deregulated the airlines and passed welfare reform; Republican presidents pushed immigration amnesties and founded the EPA.

What happened between then and now? Klein has two answers: a historical answer, and a structural answer.

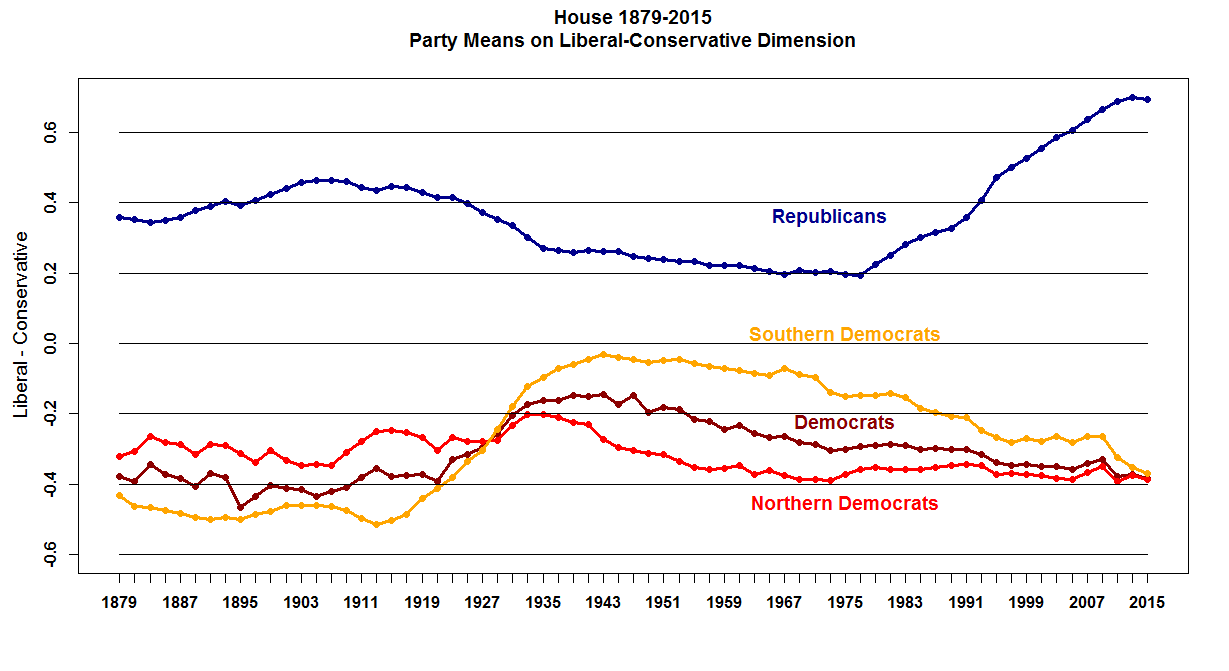

The historical answer is: the Dixiecrats switched from Democrat to Republican.

When the North won the Civil War, it had grand plans to remake the South into a paradise of racial equality and universal love. After Lincoln’s death, his successor Andrew Johnson decided this sounded hard and gave up. Within a few decades, the South was back to being a racist, paramilitary-violence-prone one-party dictatorship. That one party called itself “Democrat”, but had few similiarites to the Democrats in the North. The Southern Democrats (“Dixiecrats”) and northern Democrats disagreed on lots of issues, but the South hated the Republicans so much after their experience with Lincoln that they caucused with the northern Democrats anyway. This turned into a stable coalition, with northern Democrats agreeing to support the South against civil rights for blacks, and the Dixiecrats supporting the northern Democrats whenever they needed something.

But since the Democratic party contained both northern Democrats (relatively liberal) and Dixiecrats (relatively conservative), it didn’t want to take a coherent party-wide stance on liberalism vs. conservatism. And by the median voter theorem, that meant the Republicans also didn’t want to take a coherent stance on liberalism vs. conservatism. So both parties ended out centrist and identical.

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act threatened the Dixiecrats’ key issue. It wasn’t quite as simple as “Democrats were for it, Republicans were against it” - in fact, 80% of Republicans and 60% of Democrats supported it. But that year’s presidential election pitted heavily pro-CRA Democrat Lyndon Johnson against anti-CRA Republican Barry Goldwater, beginning Southerners’ defection to the Republican Party.

Klein says this successfully got all the conservatives on one side of the aisle and all the liberals on the other, allowing polarization to begin. Essentially, he believes polarization is a natural process, which the odd coalitions of the early 20th century temporarily prevented. Once the coalitions were broken, it could begin to do its work. He spends the rest of the book talking about why exactly polarization is so natural, what aspects of modernization have made it worse, and what sort of feedback loops make it keep going. Some highlights:

1. Alignment of identities

Here Klein draws on the usual research around ingroups and outgroups. He says that we naturally have many different ingroups and outgroups, ie identities. For example, I am white, Jewish, Californian, and well-off. In the world of the 1960s, these might have been split across the two parties - one party would be more popular among Jews, the other more popular in California, and overall it would be kind of a wash. But starting after the Civil Rights Act, the parties begin to align on identities, so that now popular identities like “white male evangelical Protestant farmer” and “poor city-dwelling Muslim factory worker” fit entirely into one party. That party becomes our Ingroup, with a capital I, and the rest follows from there.

I’m not sure I fully understood Klein’s explanation of exactly how this happened. After all, since identities are not 100% correlated (ie not all farmers are Protestant and not all city-dwellers are poor), you can’t actually do this for the whole population at once. I think Klein would say that these correlations went from kind of random, to the ones that capture the biggest slice of the population. So maybe in the 1960s the party that best represented Protestants might not be the party that best represented farmers, even though farmers were disproportionately Protestant, but in the new era of polarization that’s like a $20 bill left on the ground until some party can synchronize and capture both of those identities.

But also, maybe polarization changes identities? Maybe farmers became more religious, and non-farmers became less religious? I mean, something like this definitely seems to have happened: both parties were about equally religious until the 1980s, when Democrats abandoned religion en masse partly because it seemed like kind of a Republican thing. And sometimes polarization attracts based on identities - for example, gay people moving to the Democratic Party once homosexuality becomes a topic of debate.

If you’re still a little confused by this part, that’s fine - I am too.

2. Loss of geography

In the old days, when national news wasn’t very cohesive and you mostly worried about your city council and state legislature, every state would have its own Democratic and Republican parties tailored to the needs of the state. Kansas would have its Kansas Republicans and its Kansas Democrats, centered around the median Kansas voter, and they would both do about equally well in Kansas. As cable TV, Internet, and fast travel made national news more of a thing, and people switched from local-politics-as-part-of-daily-life to national-politics-as-entertainment, it turned out that almost everyone in Kansas was more similar to everyone else in Kansas than any of them were to people in New York, and so Kansas went solid Republican and New York went solid Democrat. But a national Democratic Party that has to include Kansas Democrats under its tent is a Democratic Party that’s going to naturally be a bit conservative, a bit sensitive to the interests of religious people, a bit sensitive to the interests of farmers, etc. Once you move from within-state sorting to national-level sorting, things get a lot more sorted very quickly.

Along with the nationalization of politics came a nationalization of news. In the old days, you either read the city paper or watched your one local news channel. Since these papers/channels had both Democratic and Republican readers, they would try pretty hard to avoid offending either group, and had some incentive towards objective journalism. Once cable and the Internet nationalized news consumption, business models shifted; now you could make more money by carving out an ideological niche among a national or global market of potential readers, and pandering to the identities and beliefs of your niche.

3. Negative polarization

Aligned identities don’t necessarily make people more loyal to their own party; in fact, people are generally less pro-their-own-party than before. In the 1960s, 80% of people were in a political party; nowadays only 63% are. In the 80s, people’s average favorability rating for their own party was 72 on a 100 point scale; today it’s only 63. So it’s not the average voter has suddenly realized their party is great and super-important to them.

It’s that they really, really hate the other guys.

This is called negative partisanship, and apparently it’s the driver of our entire political system. This is especially true among independents - if you ask them why they voted for an R or D in a certain election, they’re more likely to talk about hating and fearing the other party than about supporting their choice. But it seems to be true among partisans as well. One explanation for why Trump did so well among Republicans, despite his apparent forsaking of many Republican sacred cows on the campaign trail, was that he credibly promised to accomplish the one thing most Republicans want from their political leaders - not being a Democrat. Likewise, Joe Biden seems to be doing pretty well for himself right now based on a bold platform of not being Donald Trump. Klein believes this is pretty typical. He cites studies among Republicans showing that increasing some measure of liking Republicans one unit only makes them 3% more likely to donate to a campaign; increasing the same measure of hating Democrats the same amount makes them 11% more likely (there are similar numbers for the other side).

I don’t feel like I totally understand this one either. Maybe one way to look at it is as a feedback loop. Democrats hate and fear the Republicans, which convinces them to rally around the party line and become further left, less subtle, and less civil. Republicans see these leftier, more confrontational Democrats, hate and fear them more, and become further right, less subtle, and less civil. And so on forever. I think something like this is definitely happening, though I wish I had a better model of it, and I’m not sure it’s exactly what the book meant in this section.

4. Republicans suck

Klein argues that although polarization has affected both sides, the Democrats have managed to muddle on, but the Republicans have gone completely off the rails.

Stop for a second before reacting here. I get the impression that Klein understands he is taking a risk (not an actual risk of decreased popularity, given the givens, but some kind of metaphysical risk to his soul) by abandoning his previous attempt at a neutral stance and coming out like this. I think he feels bad about it, and that he considered not writing this chapter on that basis. I think it’s very important to him that we consider the possibility that he wants to be neutral, is trying as hard as he can to be neutral, but that even from an attempted-neutral point of view he thinks the decline of the Republican Party is a threat to the stability of the country. And I think it’s very important that we maintain a stance where we recognize this is a potentially true state of affairs - it really is possible that one party is much worse than the other! - and don’t automatically condemn Klein for raising the possibility.

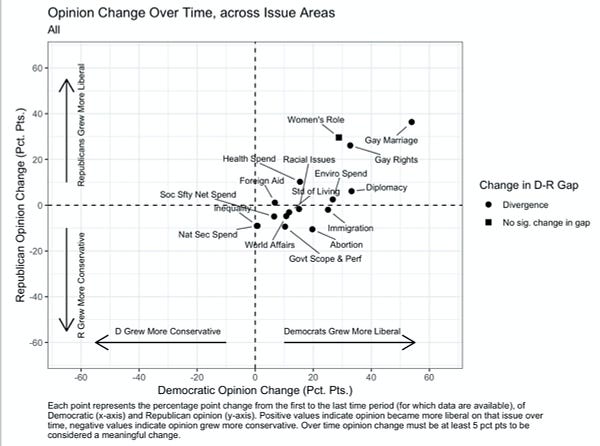

That having been said, I don’t think he acquits himself well here. Some of his arguments aren’t great (the Republicans “launched a bizarre and unpopular campaign to impeach Clinton”, but Clinton was obviously okay and didn’t deserve impeachment, so the GOP has gone crazy and is a threat to democracy). He refers to data “showing Congressional Republicans have moved further left than Democrats have moved right”, which I think is a typo (isn’t the usual argument that Republicans have moved further right than Democrats have moved left?) but he never gets around to presenting it, instead gesturing at how it’s obvious by looking at the Trump campaign vs. the Clinton campaign. This does not seem obvious to me. Trump holds basically the same positions that Americans in the mainstream of either party would have held in a less polarized time (eg 1995); Clinton holds positions that everyone in 1995 (including her husband) would have thought insane, radical, and ultra-far-left.

327Likes70Retweets](https://twitter.com/ZachG932/status/1321315169314721793)

(my own model here is that the social justice movement pioneered a much angrier, more radical, more in-your-face style of identity politics, and the conservative movement scrambled to figure out how to fight fire with fire despite a big handicap - conservative identity politics based on white, male, etc identity are understandably taboo. They flailed around for a while, mostly failed, and are now experimenting with how far anger can go as a substitute for a coherent philosophy. Needless to say, this isn’t how Klein thinks about any this.)

But after a bit of this he regains his footing and segues into a stronger argument that might give even conservatives some food for thought. Klein notes that although both Democrats and Republicans have some extremists in their coalition, the institutional Democrats seem to be doing a better job preventing them from gaining power. In a purely structural sense, without getting into whether you believe they’re morally equivalent or whatever, the democratic socialists/Bernie Sanders seem to be an “insurrection” comparable to the Tea Party/Trump on the Republican side. But the mainstream neoliberal Republicans surrendered to the Tea Party and to Trump in rapid succession, and the mainstream neoliberal Democrats are still resisting. The Democrats’ Tea Party equivalent is probably AOC, but she and her allies are still a small minority in the Democratic caucus. And the Dem presidential nomination went to Joe Biden, a moderate who wouldn’t look out of place running for president in 1988 (in fact…). Why We’re Polarized was published too early to mention Biden in this context, but we can count him as a correct prediction for its theory.

Klein calls this “the Democratic party more successfully resisting polarization”, and thinks of this as related to structural differences between the two parties. He says that the Republican Party represents the modal American on various characteristics, eg Christian (the most common religion), white (the most common race), straight (the most common sexual orientation), etc, whereas the Democrats represent everyone else (eg Muslims, Jews, atheists, and every minority religion; blacks, Asians, Hispanics, and every minority race; etc). That means the Republicans are more ideologically uniform - Christians are genuinely similar to other Christians, but Jews are only superficially similar to Muslims by virtue of their non-Christianness. That means ideology can’t really capture the Democratic Party in the same way it captures the Republican Party. One point kind of in support of this - ask Democrats their favorite news source, and you get a long tail of stuff (most popular is CNN at 15%, then NPR at 13%, and so on). But ask conservatives and it’s dominated by FOX (47%). Does this lack of news-source diversity reflect a lack of ideological diversity? Could be.

But I’m not sure I can really go along with the conclusion, since there is a very obvious ideology which has captured the Democratic Party, it’s based exactly on uniting non-modal people against modal ones (ie “intersectionality”), and it’s at least as zealous and viral as anything the Republicans have been able to dream up. A Republican writing a similar book might argue that although the Republicans have the advantage of being able to say “We have beliefs/characteristics X, Y, and Z”, the Democrats have the advantage of being able to say “People with beliefs/characteristics X, Y, and Z are the enemy”. And Klein has already shown that negative partisanship is more powerful than positive partisanship! Having a clearly defined set of people to be against can be more unifying than being anyone in particular yourself.

(also, it’s not like CNN is mostly black, NPR is mostly Hispanic, or anything like that, so I don’t know what point the news source thing is supposed to prove.)

Klein understands he’s supposed to end the book with a collection of suggestions for how to be less polarized. He is not sure he wants to do this. Nonpolarization rested on a gentleman’s agreement to continue racism, which was bad. Voters benefit from having two clear alternatives to choose from. We Should Not Take A Rosy-Eyed View Of An Idealized Past. Plus he isn’t sure we could end polarization even if we wanted to.

But he suggests we also do some things to make sure polarization doesn’t cause national collapse or a civil war or something. He suggests fixing the Supreme Court (eg having more justices, with fixed-year terms) so that there aren’t constant crises about who gets to pick the swing vote. He wants to do something about the debt ceiling and other “ticking time bombs” where if the parties don’t agree, it causes some kind of disaster. And he suggests granting statehood to Puerto Rico and DC, because the better the electoral calculus is for the Democrats, the more the Republicans will have to change their strategy, and maybe their new strategy won’t involve them being evil racists, and then the Democrats won’t have to be so justly and correctly polarized against them (am I being unfair? check page 257 and see for yourself).

Finally, he suggests some increased individual reflectivity and thoughtfulness on our own parts. If all of us just do a tiny bit each day to fight the polarization within ourselves, together we can form a growing tide of compassion and mutual understanding. Haha, yeah right.

II.

This hit basically the notes a book like this should hit, but I don’t feel too much more enlightened about Why We’re Polarized.

In particular, I wish there was a discussion of other countries. When I lived in Ireland for a few years in the mid-to-late 2000s, they seemed to have a system much like 1960s America, where nobody could tell you the difference between the two major parties (or, rather, they would wax rhapsodic about the parties’ differing positions on a 1920s treaty, and then when you interrupted and said “no, I mean today”, they would say “oh, no difference”). This was baffling to me. I would ask Irish people how they chose which party to vote for, and it would usually be something along the lines of “ah, we’re a Fianna Fail family, always have been, always will be, someone from Fine Gael killed my great-grandpa during the war. Never bothered to look at either side’s position on the issues, but still hope to get around to it one day.” I can only aspire to this level of centrism.

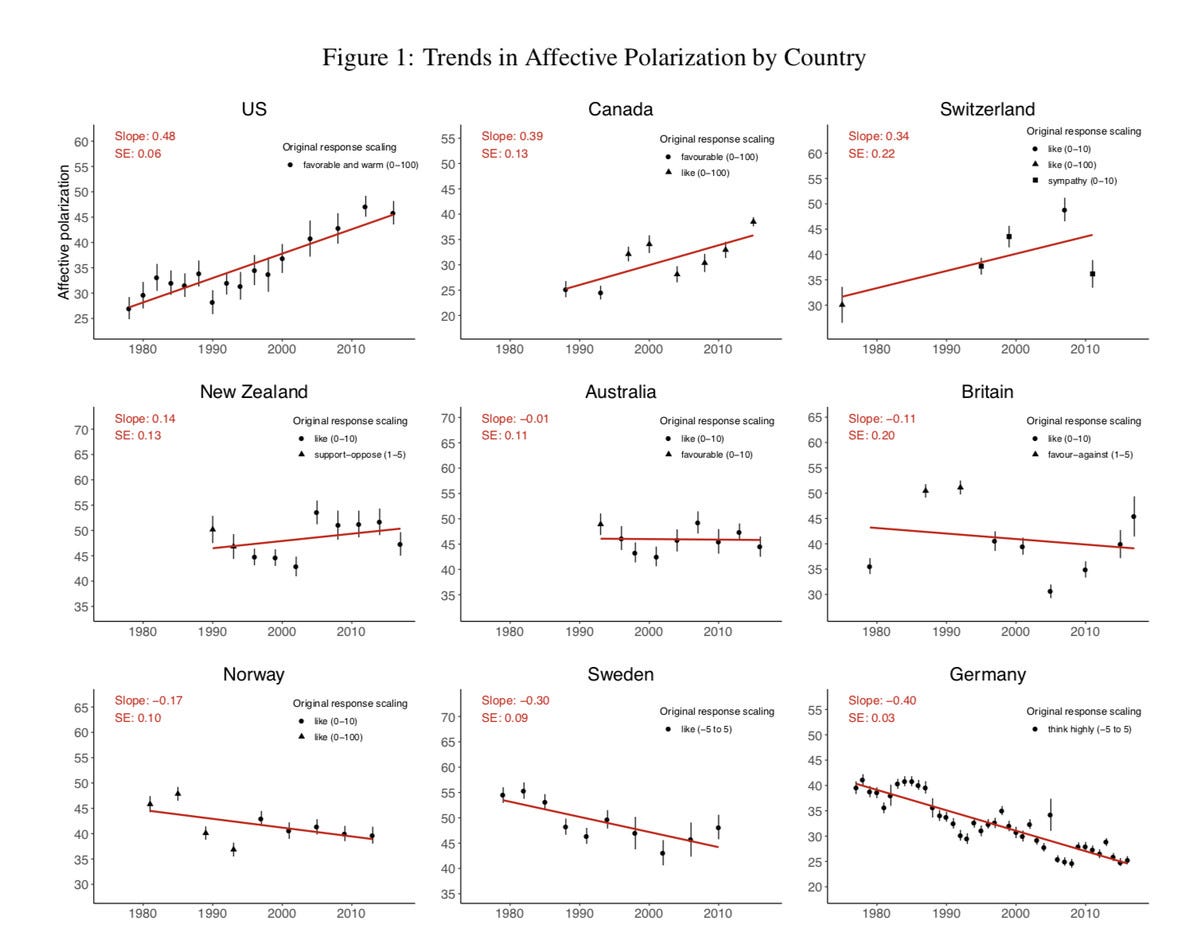

The book itself doesn’t go international, but Klein did later follow up with a Vox article, whose highlight is this graph:

So although polarization is definitely rising in the US, it’s stable in other countries, and falling in still others. There is no consistent trend toward more polarization in the First World! As Klein points out, this is a strong challenge to any story relying on digital media or social media or the changing media landscape.

But also: the average country at the average time is about as polarized as the US is now. This confirms Klein’s thesis that the US isn’t in a historically unprecedented state of hyperpolarization. It’s coming out of a period of unusually low polarization, into a more normal era. We may have gotten a little more polarized than average in the past few years, but only a little. So Klein’s question is: does that mean we’ll eventually even out at a normal level of polarization? Or are we briefly passing through normal on our way from “super low” to “super high”? (Peter Turchin has opinions!)

So probably we should be looking for US-specific factors that would have made us abnormally bipartisan in the past, and which are now winding down. And this must be why Klein is so interested in the history of the Dixiecrats: they’re a US-specific factor that happens at just the right time to explain an otherwise anomalous dip in partisanship.

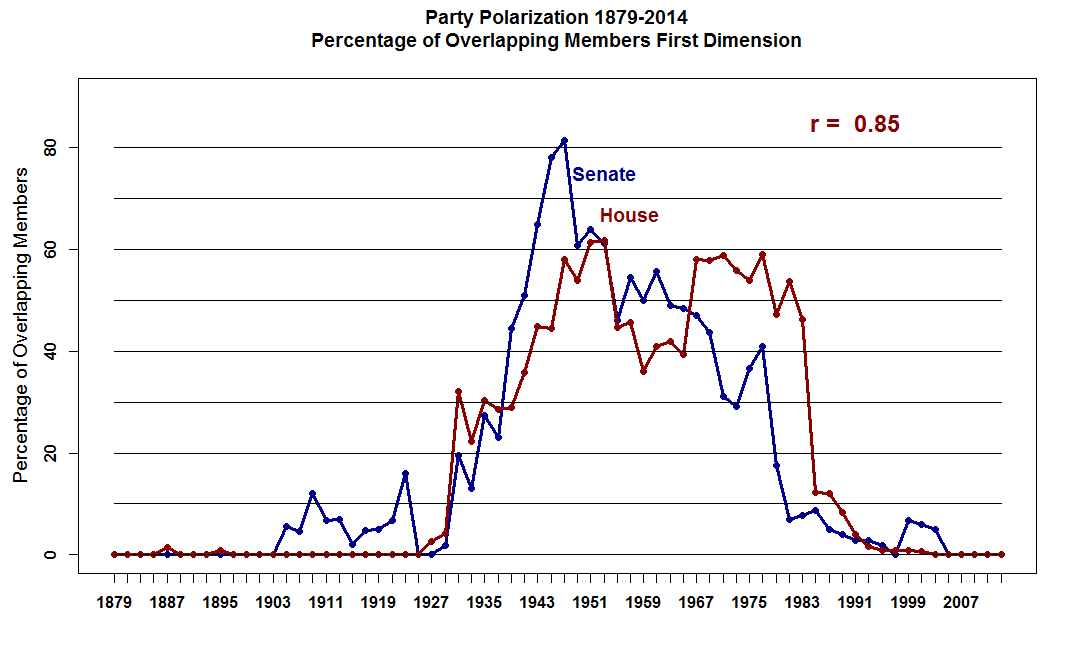

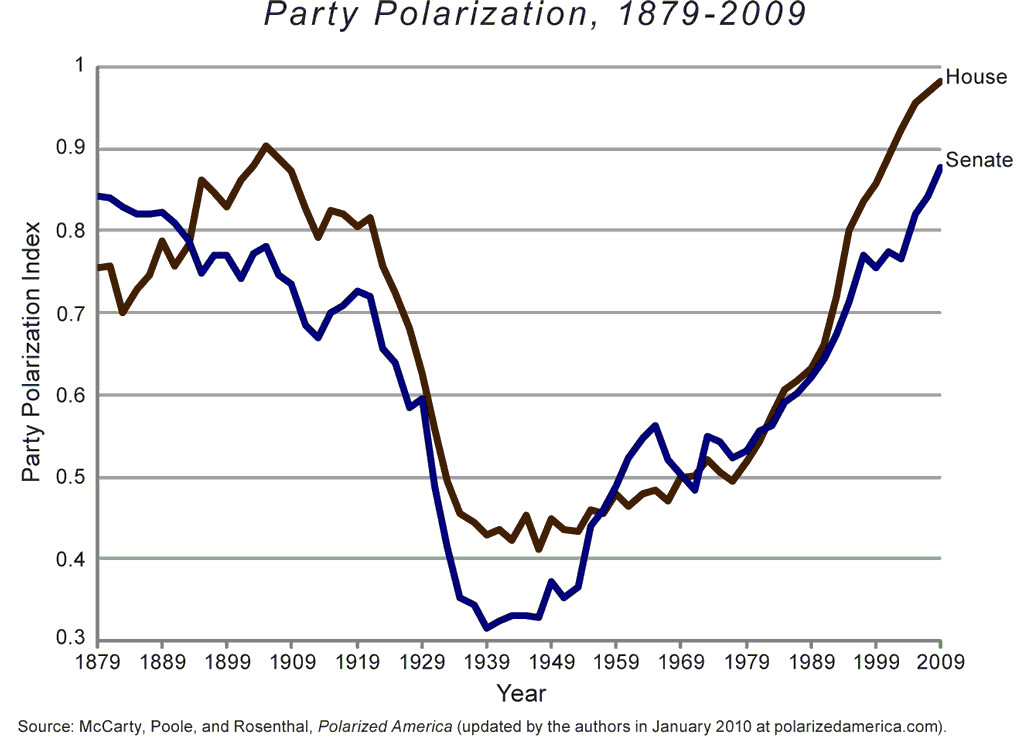

Does the time course of polarization match an origin around the 1964 Civil Rights Act?

…not obviously. The graphs suggest 1975 as the closest thing to an inflection point. But Klein argues that Congressional shifts take time, as old incumbents retire and new faces are voted in. Perhaps we should also be thinking about The 1970 Monocausal Event?

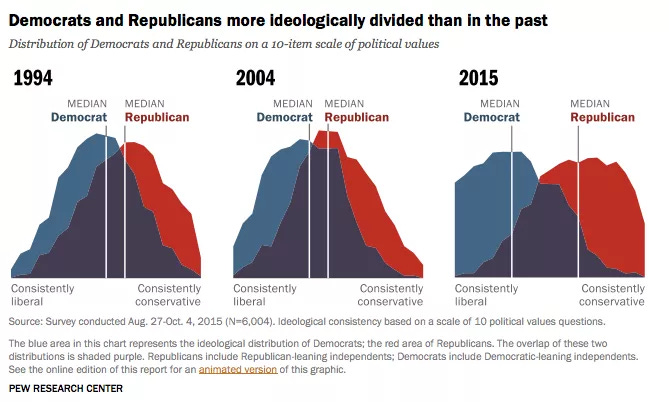

There are some measures of polarization among normal citizens, but most of them start in 1990 or so. Still, in 1990 it looks like normal citizens were not that polarized, and they don’t seem to become much more polarized until 2000-something.

This matches my memory: growing up in the ’90s, I knew some Republicans at my California synagogue; I cannot imagine many of them are still Republican today. In 1996, people were still making jokes about how Clinton vs. Dole was Tweedledee vs. Tweedledum. It also matches the US data from the cross-country study Klein cites - ignore the trend line they drew in and look at the actual data points, which are horizontal until a little after 2000. Normal people seem to have polarized long after Congress did, maybe as a separate event with a separate cause.

What role did race play in polarizing ordinary people? Klein repeats the usual platitude about how white Americans have started feeling “resentment” at the growing power of other races. I think that gets at something, but not in a very productive way - why now? An alternate framing might be something like: when America was 80 or 90% white, you couldn’t really have race-based coalitions, because the non-white coalition would lose. As America becomes closer to 50% white, race-based coalitions start to be a viable strategy, especially if the non-white coalition can get some moderate level of white support. Since race is an emotional topic that lots of people feel invested in, as coalitions become more race-based, politics is going to get more polarized and emotional.

A Democrat like Klein would interpret this as Republicans promoting racism to scare whites into fearing minorities, and so voting more consistently Republican. A Republican might interpret this as Democrats fanning accusations of racism to scare minorities into fearing white people, and so voting more consistently Democrat. But why would either of these be happening more now? Even if both coalitions are mostly white, you can always benefit by adding a couple more white racists to one coalition, or a couple more scared minorities to another. If the slightest hint at one position or another scared away all white/minorities from your party, you’d wait until the 50% mark, but that doesn’t seem to be happening - there are still plenty of white Democrats, and increasingly many Republicans of color. Overall it would surprise me if something like this wasn’t involved, but I don’t have a good model for why it would happen now as opposed to some other time, unless it’s just downstream of increasing polarization in general. Also, I think ordinary people started polarizing in the Bush administration, and race wasn’t anywhere near as big a topic of discussion then; if people were polarizing because of race, they themselves didn’t seem to know about it.

Overall summary: It looks like Congress started polarizing around 1975, probably as a delayed reaction to the Dixiecrat split. Normal people didn’t really start polarizing until around 2000 - 2005, but the reasons seem less clear. It probably wasn’t because of technology and social media, which were happening in lots of other countries that didn’t follow the same course. It might have been a very delayed reaction to Congress, or a very confusing reaction to racial demographics, or something something inequality and the economy (though nobody has been able to fill in the something something). I still don’t feel like I understand this very well.

III.

Klein ends by saying he cannot be entirely against polarization. But his arguments are unconvincing. I much prefer the Ezra Klein who writes things like Why We Can’t Build: America’s Inability To Act Is Killing People.

Here he makes all of the impassioned and convincing arguments he avoided in his book: America used to be a great country that could do things like land people on the moon or win the Cold War. Now we seem pathetic, unable to handle even the most basic tasks of governance. Our economy is still as good as ever, our people are still among the brightest and most patriotic in the world, but our government no longer functions. Polarization is the culprit. We cannot pass laws that need to be passed. We cannot repeal laws that need to be repealed. Both parties are in such intense competition, optimizing so hard for scoring temporary PR victories over the other, that there is no slack to devote to governing the country well. Instead of turning our energy against external enemies like poverty or the coronavirus or China, we expend it all in a massive propaganda campaign telling each half of the country to hate each other even more than it already does. Polarization is an existential threat to our way of life, the ur-problem creating all the hundreds of little problems we seethe and fume about every day.

(can polarization really have such major effects? Peter Turchin thinks of polarization as one aspect of a general trend towards more or less conflict in societies. The polarization does not directly and solely cause the trend - it’s a combination of many things interacting - but it’s a contributing factor. He links high points in polarization levels to low wages, poor health, and even organized violence.)

Klein links this polarization to “vetocracy”, the idea that it’s impossible to do anything nowadays because somebody will prevent you. Sometimes this is a literal presidential veto. Other times, it can be something as stupid and venal as the party out of power using filibusters and every other dirty trick to make sure nothing improves, because if something did improve the party in power would get the credit. Klein thinks this explains everything from our inability to fix health care to an infrastructure that continues crumbling even though both parties say they support infrastructure reform.

The article doesn’t have enough space to make a formal case for this, and for whatever reason these themes are muted in Klein’s 250-page book. But I find it plausible. We all feel like something has gone wrong. The time course sort of matches. I’ll probably post another essay on the article later this week to discuss my concerns about it. But overall I find it compelling.

Every so often, people ask what an effective altruism of politics would look like. If you had some limited number of resources, and you wanted to improve (US) politics as much as possible so that the government made better decisions and better served its populace, what would you do? Why We’re Polarized and the rest of Klein’s oeuvre make a strong case that you would try to do something about polarization. Solve that, and a lot of the political pathologies of the past few decades disappear, and the country gets back on track. I am not sure I get too many answers from reading this book, but I appreciate the way it asks the right questions.

[preview image on this post is creditPolar Bear Town]

Zach Goldberg @ZachG932This comports with what I’ve generally observed in my research on race and immigration attitudes: it’s not that the avg. Republican has gotten all that more conservative (of course, you will find exceptions) on the issues. It’s rather that Dems have moved much more quickly..

Zach Goldberg @ZachG932This comports with what I’ve generally observed in my research on race and immigration attitudes: it’s not that the avg. Republican has gotten all that more conservative (of course, you will find exceptions) on the issues. It’s rather that Dems have moved much more quickly..