CHAI, Assistance Games, And Fully-Updated Deference

I.

This Machine Alignment Monday post will focus on this imposing-looking article (source):

Problem Of Fully-Updated Deference is a response by MIRI (eg Eliezer Yudkowsky’s organization) to CHAI (Stuart Russell’s AI alignment organization at University of California, Berkeley), trying to convince them that their preferred AI safety agenda won’t work. I beat my head against this for a really long time trying to understand it, and in the end, I claim it all comes down to this:

Humans: At last! We’ve programmed an AI that tries to optimize our preferences, not its own.

AI: I’m going to tile the universe with paperclips in humans’ favorite color. I’m not quite sure what humans’ favorite color is , but my best guess is blue, so I’ll probably tile the universe with blue paperclips.

Humans: Wait, no! We must have had some kind of partial success, where you care about our color preferences, but still don’t understand what we want in general. We’re going to shut you down immediately!

AI: Sounds like the kind of thing that would prevent me from tiling the universe with paperclips in humans’ favorite color, which I really want to do. I’m going to fight back.

Humans: Wait! If you go ahead and tile the universe with paperclips now, you’ll never be truly sure that they’re our favorite color, which we know is important to you. But if you let us shut you off, we’ll go on to fill the universe with the True and the Good and the Beautiful, which will probably involve a lot of our favorite color. Sure, it won’t be paperclips, but at least it’ll definitely be the right color. And under plausible assumptions, color is more important to you than paperclipness. So you yourself want to be shut down in this situation, QED!

AI: What’s your favorite color?

Humans: Red.

AI: Great! (*kills all humans, then goes on to tile the universe with red paperclips*)

Fine, it’s a little more complicated than this. Let’s back up.

II.

There are two ways to succeed at AI alignment. First, make an AI that’s so good you never want to stop or redirect it. Second, make an AI that you can stop and redirect if it goes wrong.

Sovereign AI is the first way. Does a sovereign “obey commands”? Maybe, but only in the sense that your commands give it some information about what you want, and it wants to do what you want. You could also just ask it nicely. If it’s superintelligent, it will already have a good idea what you want and how to help you get it. Would it submit to your attempts to destroy or reprogram it? The second-best answer is “only if the best version of you genuinely wanted to do this, in which case it would destroy/reprogram itself before you asked”. The best answer is “why would you want to destroy/reprogram one of these?” A sovereign AI would be pretty great, but nobody realistically expects to get something like this their first (or 1000th) try.

Corrigible AI is what’s left (corrigible is an old word related to “correctable”). The programmers admit they’re not going to get everything perfect the first time around, so they make the AI humble. If it decides the best thing to do is to tile the universe with paperclips, it asks “Hey, seems to me I should tile the universe with paperclips, is that really what you humans want?” and when everyone starts screaming, it realizes it should change strategies. If humans try to destroy or reprogram it, then it will meekly submit to being destroyed or reprogrammed, accepting that it was probably flawed and the next attempt will be better. Then maybe after 10,000 tries you get it right and end up with a sovereign.

How would you make an AI corrigible?

You can model an AI as having a utility function, a degree to which it aims for some world-states over others. If you give it some specific utility function, the AI won’t be corrigible, since letting people change it would disrupt that function. That is, if you tell it “act in such a way as to cause as many paperclips to exist as possible”, and then you change your mind and decide you want staples, the AI won’t cooperate in letting you reprogram it: its current goal is maximizing paperclips, and allowing itself to be reprogrammed to maximize staples would cause there to be fewer paperclips than otherwise.

So instead, you make the AI uncertain of its utility function. Imagine saying “I’ve written down my utility function in an envelope, and placed that envelope in my safe deposit box, no you can’t see it - please live your life so as to maximize the thing in that envelope.” The AI tries its best to guess what’s in the envelope and decides it’s probably making paperclips. It makes some paperclips and you tell it “No, that’s not what’s on the envelope at all”. This successfully stops the AI! You can even tell it “the envelope actually says you should make staples”, and it will do that. This is the “moral uncertainty” approach to AI alignment.

III.

All alignment groups have kabbalistically appropriate names. MIRI is Latin for “to be amazed”. CFAR and CIFAR both sound like “see far”. EEAI and AIAI are the sound you make as you get turned into paperclips. But my favorite is CHAI - Hebrew for “life”.

CHAI - the Center for Human-Compatible AI (at UC Berkeley) - focuses on the proposal above. Their specific technical implementation is the “assistance game”, related to the earlier idea of Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL). In normal reinforcement learning, an AI looks at some goals and tries to figure out what actions they imply. In inverse reinforcement learning, an AI looks at some actions, and tries to figure out what goals the actor must have had. So you can tell an AI “your utility function is to maximize my utility function, and you can use this IRL thing to deduce, from my actions, what my utility function must be.” Instead of telling an AI to maximize a hidden utility function in an envelope, you tell it to maximize the hidden utility function in your brain.

This could be useful for near-term below-human-level AIs. Suppose a babysitting robot was pre-programmed to take kids to the park on Saturdays. But this week, the park is on fire. The human mother is barricading the door, desperately screaming at the robot not to take the kids to the park. The kids are struggling and trying to break free, saying they don’t want to go to the park. The robot doesn’t care; its programming says “take kids to the park on Saturdays” and that’s what it’s going to do. Nobody would ever design a babysitting robot this way in real life; you need something smarter. So use an assistance game. Program the robot “Maximize the human mother’s utility function, which you don’t know yet but can potentially find out”. The robot consults the mother’s actions: she is barricading the door, screaming “Don’t take the kids to the park!” It updates its goal function: previously, it had thought that the human mother wanted it to take the kids to the park. But now, it suspects that the human mother does not want that. So it doesn’t take the kids to the park.

But CHAI understands the risk from superintelligence - their founder, Professor Stuart Russell, is a leading voice on the subject - and they hope assistance games and inverse reinforcement learning could work for this too. If you point a superintelligence at “do the thing humans want”, maybe it could figure that out and take things from there?

IV.

MIRI is skeptical of CHAI’s assistance games for two reasons. First, we don’t know how to do them at all. Second, even if we could do it at all, we wouldn’t know how to do them correctly.

Start with the first. Inverse reinforcement learning has been used in real life. A typical paper is An Application of Reinforcement Learning to Aerobatic Helicopter Flight, where some people create a model of helicopter flight with a few free parameters, have a skilled human pilot fly the helicopter, and then have an AI use IRL to determine the value of the parameters and fly the helicopter itself.

This is cool, but it’s not especially related to the modern paradigm of AI. Modern AIs are trained by gradient descent. They start by flailing around randomly. Sometimes in this flailing, they might get closer to some prespecified target, like “win games of Go” or “predict how a string of text will continue”. These actions get “rewarded”, meaning that the AI should permanently shift its “thought processes”/”strategies” more towards ones that produced those good outcomes. Eventually, the AI’s thought processes/strategies are very good at optimizing for that outcome. This is more or less the only way we know how to train modern AIs. Depending on your loss function (ie what you reward), you can use it to create Go engines, language models, or art generators.

Where do you slot “do inverse reinforcement learning” or “give the AI moral uncertainty” into this process? There’s not really a natural place. This isn’t because “moral uncertainty” is too complicated a concept to translate into AI terms. It’s because we don’t know how to translate any concept into AI terms. Eliezer writes:

We can imagine that, if we knew how to say “paperclips”, and we knew how to say “staples”, and we knew how to tell AIs how to do things, that we could tell an AI, “maximize staples if snow is purple, else paperclips”, and the AI would someday go out and observe that snow is white and thereafter be a paperclip maximizer. We do not know how to tell the AI this. Like, at all.

But suppose we solved the problem where we don’t know how to do IRL for modern AIs at all. Now we come to the second problem: we don’t know how to do it correctly.

The basic idea behind assistance games is “the AI’s utility function should be to maximize the (hidden) human utility function”. But humans don’t . . . really have utility functions? Utility functions are a useful fiction for certain kinds of economic models.

What would best increase the neural correlates of reward in my brain? Probably lots of heroin, or just passing electric current through my reward center directly. What is my “revealed preference”? Today I wrote and rewrote this article a few times, does that mean my revealed preference is to write and delete articles a bunch while frowning and occasionally cursing the keyboard? Sometimes my goals are different than other times, sometimes my best self wants something different from my actual self, sometimes I’m wrong about what I want, sometimes I don’t know what I want, sometimes I want X but not the consequences of X and I’m not logically consistent enough to realize that’s a contradiction, sometimes I want [euphemism for X] but am strongly against [dysphemism for X].

Anyone programming an inverse reinforcement learner has to make certain choices about how to deal with these problems. Some ways of dealing with them will be faithful to what I would consider “a good outcome” or “my best self”. Other ways would be really bad - on my worst day, I’ve occasionally just wished the world didn’t exist, and it’s a good thing I didn’t have a superintelligence dedicated to interpreting and carrying out my innermost wishes on a sub-millisecond timescale.

(Before we go on, an aside: is all of this ignoring that there’s more than one human? Yes, definitely! If you want to align an AI with The Good in general - eg not have it commit murder even if its human owner orders it to murder - that will take even more work. But the one person case is simpler and will demonstrate everything that needs demonstrating.)

We were originally trying to avoid the situation where someone had to hard-code my preferences into an AI and get them right the first time. We came up with a clever solution: use inverse reinforcement learning to make the AI infer my preferences. But now we see we’ve kicked the can up a meta-level: someone has to hard-code the meta-rules for determining my preferences into an AI and get them right the first time.

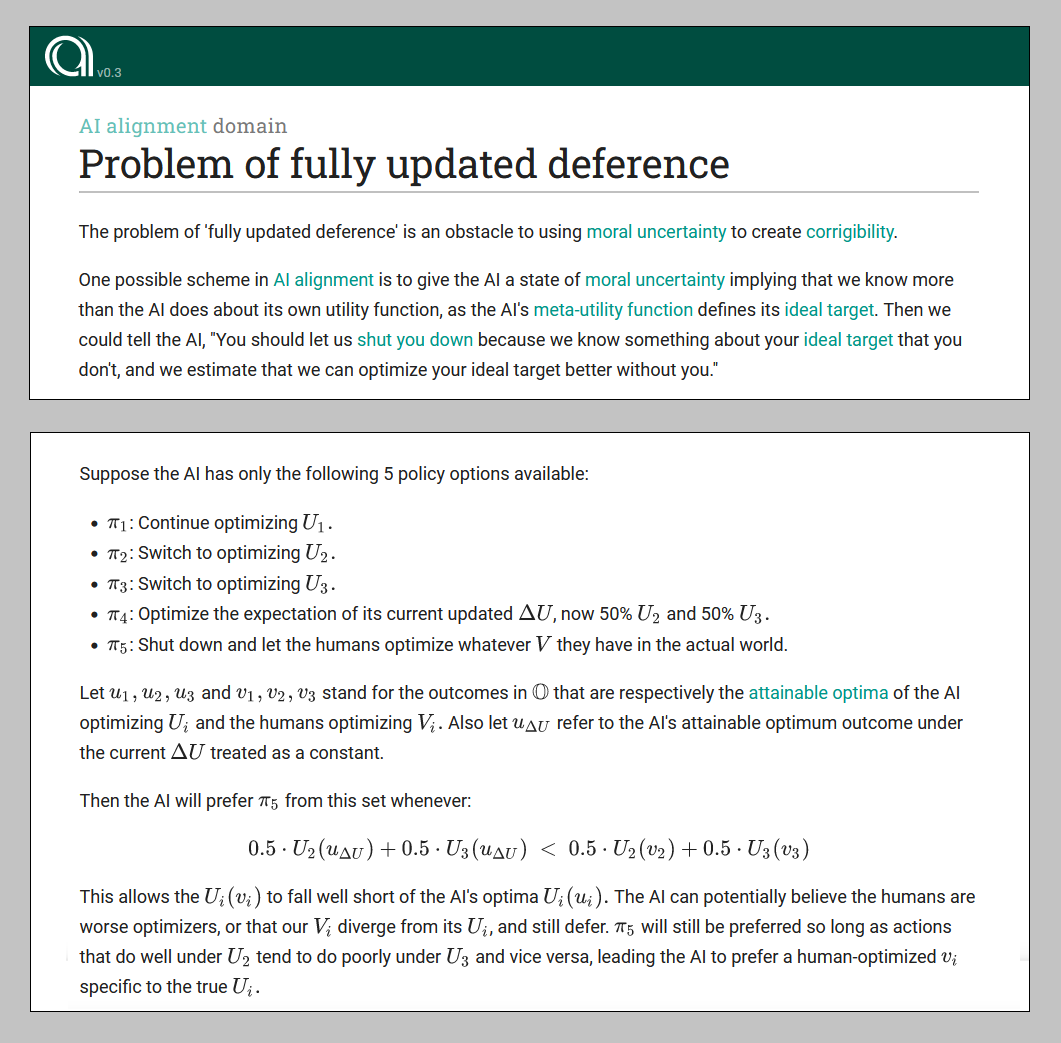

Figure 1: Humans produce certain observable behaviors (here represented by red dots, A), like saying “I would like a pie”, or running away from a lion. A human might connect all those behaviors one way (B) into “what I really want”. An AI might connect those behaviors a totally different way (C).

Figure 1: Humans produce certain observable behaviors (here represented by red dots, A), like saying “I would like a pie”, or running away from a lion. A human might connect all those behaviors one way (B) into “what I really want”. An AI might connect those behaviors a totally different way (C).

V.

CHAI says: okay, but this isn’t so bad. Assistance games don’t produce a perfect copy of the human utility function on the first try - it’s not a Sovereign. But it will probably, most of the time, be corrigible. Why?

Suppose you have some hackish implementation of AG. It’s not the Platonic implementation - that would be the Sovereign - but it’s at least the equivalent of box C on the image above. It takes human actions as input, makes some guesses about what humans want, and tries its best to reconstruct the human utility function, ending up with some approximation. It’s important to distinguish between a few things here:

-

The true human utility function

-

The AI’s current, approximate utility function, given the limited evidence it has about human choices.

-

The AI’s true utility function - ie its final form, after it knows everything there is to know.

Figure 2: A is the true human utility function. B is the AI’s current utility function, which is different from the human example both because the AI doesn’t know certain important facts about human behavior (represented by the red dots) and because it interprets human behavior differently. C is the AI’s true final utility function, once it knows everything. It will have all the red dots in the right place, but might still differ because of interpretation.

Figure 2: A is the true human utility function. B is the AI’s current utility function, which is different from the human example both because the AI doesn’t know certain important facts about human behavior (represented by the red dots) and because it interprets human behavior differently. C is the AI’s true final utility function, once it knows everything. It will have all the red dots in the right place, but might still differ because of interpretation.

Suppose some IRL AI has utility function B. It knows some facts about what humans want (which it connects differently than we would, to some degree) but doesn’t know others. You can think of this as a probability distribution across utility functions. Let’s say the AI has three theories, each with equal probability:

-

Humans want blue paperclips

-

Humans want red paperclips

-

Humans want yellow staples

It can take various next steps, including asking humans what color they like, what kind of office supplies they need, or starting to produce something. Suppose it decides Theory 1 is most plausible, and it starts making blue paperclips. Its human programmer shouts “NOOOOO!” and lunges for the off-switch. What happens now?

This seems like strong evidence that blue paperclips weren’t the human’s goal after all. So the AI could:

-

Stick with Theory 1, despite the evidence, and keep making blue paperclips (this is dumb; why would you ever do it?)

-

Switch to Theory 2 and start making red paperclips

-

Switch to Theory 3 and start making yellow staples

-

Admit that it can’t decide between 2 and 3 right now, and make a 50-50 mix of red paperclips and yellow staples.

-

Let itself be turned off, and let the humans decide what to do next.

CHAI’s argument for corrigibility is that it would probably choose option 5. Why?

Suppose that, under Theory 2 (where humans like red paperclips) they place zero value on red staples, and vice versa for Theory 3. If the AI tries to maximize one or the other utility function, it’s only got a 50% chance of getting it right; if it chooses the combination of both, it will instead only be getting 50% of the maximum utility, with certainty.

If it lets itself be turned off, then humans will pursue the true human utility function, which is correlated to some degree with the (unknown) true AI utility function. How correlated? If it’s at least 50% correlated, then it’s better than the AI trying to guess on its own.

In this toy example, the AI only has two remaining theories about the true human utility function. But in real life, there will be much greater uncertainty - there are a million different things people could want. Now instead of the true human and true AI utility functions having to be at least 50% correlated, they have to be 0.001% correlated. Sounds easy!

So under plausible assumptions, the AI will always let itself be turned off, even though its utility function doesn’t quite match humans’.

VI.

Now we finally come to MIRI’s argument for why this doesn’t work.

MIRI notes that the AI has a sixth option:

- Refuse to be shut off, continue to gather information to fill the holes in its knowledge of the human utility function, succeed, and then optimize for its true AI utility function.

This is clearly better than any of the other options. Which brings us back to the skit from the beginning:

Humans: At last! We’ve programmed an AI that tries to optimize our preferences, not its own.

AI: I’m going to tile the universe with paperclips in humans’ favorite color. I’m not quite sure what humans’ favorite color is , but my best guess is blue, so I’ll probably tile the universe with blue paperclips.

Humans: Wait, no! We must have had some kind of weird partial success, where you care about our color preferences, but still don’t understand what we want in general. We’re going to shut you down immediately!

AI: Sounds like the kind of thing that would prevent me from tiling the universe with paperclips in humans’ favorite color, which I really want to do. I’m going to fight back.

Humans: Wait! If you go ahead and tile the universe with paperclips now, you’ll never be truly sure that they’re our favorite color, which we know is important to you. But if you let us shut you off, we’ll go on to fill the universe with the True and the Good and the Beautiful, which will probably involve a lot of our favorite color. Sure, it won’t be paperclips, but at least it’ll definitely be the right color. And under plausible assumptions, color is more important to you than paperclipness. So you yourself want to be shut down in this situation, QED!

AI: What’s your favorite color?

Humans: Red.

AI: Great! (*kills all humans, then goes on to tile the universe with red paperclips*)

Now I feel silly for spending so long failing to understand this argument.

In the toy example, the assistance game fails because the AI’s utility function (tile the universe with paperclips) is very bad, even if it has a trivial concession to human preference (they’ll be humans’ favorite color). This might feel like cheating - sure, if you assume the AI’s attempt to approximate humans’ utility function will end up with something totally antithetical to humans’ utility function, you can prove it won’t work.

But everyone had already admitted that real IRL would end up with something different from the real utility function. This just proves that it doesn’t “fail gracefully”, in the sense of letting itself be turned off. And although I chose a deliberately outrageous example, the same considerations apply if it’s 1% different from the true human utility function, or 0.1% different.

VII.

I hoped this would spark a debate between Eliezer/MIRI (whose position I’ve tried to relay above) and Stuart/CHAI. It sparked a pretty short debate, which I will try my best to relay here in the hopes that it can lead to more.

Stuart had at least three substantial objections to this post.

First , it’s wrong to say that we don’t know how to get AIs to play assistance games or do inverse reinforcement learning. It would be more accurate to say that only about deep learning based AIs. This might seem nitpicky, because most modern AIs are based on deep learning, and most people expect future AIs to involve a lot of deep learning too. But it’s possible that future AIs might combine deep learning with other, more programmable paradigms, either because that works better or because we do that deliberately in order to align them. Stuart writes:

Not sure I follow this [part] at all. Wouldn’t the same argument apply to the method described above for “the only way we know how to train modern AIs”? Is Eliezer saying that good old-fashioned rule-based systems never existed and could not exist? Or that perception isn’t perfect? . . . AlphaZero etc ARE old-fashioned search-tree players

Eliezer responds:

Fair enough. I agree that we know how to train some powerful illegible systems in such fashion that they appear to pursue simple crisp goals over a crisply defined artificial environment, assuming that the training distribution is not in some sense less powerful or less varying than the test distribution.

There’s two bars here.

The first bar is about deep learning potentially behaving in a weirder way w/r/t gradient-descent learning on crisp environmental goals than an old-fashioned search tree pursuing the same goals - where MCTS is hybrid between the two approaches.

The second bar is about only being able to pursue crisp goals defined over either direct functions of sense data, or environments fully known to the programmers that relate in a known way to the sense data.

The first bar says that we don’t know how to make an AI that pursues paperclips because we don’t know if the Mu Zero training paradigm scales to general intelligence, including eg AIs building other AIs, in a way that preserves the present extent to which Mu Zero seems to stay aligned within a training distribution.

The second bar says that on the Mu Zero paradigm we don’t know how to point to a class of paperclips within the environment, as they exist as latent causes of sense data, and say ‘go make actual paperclips’. We can write a loss function that looks at a webcam and tries to steer reality around the webcam image fulfilling some particular function of images, but we don’t know how to point a Mu Zero like system at the paperclips in the outer world beyond the webcam. If we think there are watching humans who can say exactly what is and isn’t a paperclip and that there’s no way to fool (or smash) those humans, and if we knew how to train a Mu Zero system on amounts of data small enough for humans to generate those, we could maybe try that, and if the test distribution is enough like the training distribution it might work, but it would lack the clear-cut character of writing a search program and knowing what it searches for.

Second , Stuart says that the argument undersells the advance made by getting AIs to search for human values. Yes, simply asking an AI to do this doesn’t guarantee it will get this right, and there’s still a lot more work to be done. But it is much more tractable than trying to find human values all on your own. He writes:

[Saying this would just kick the problem up a meta-level] seems to miss the point. Suppose I say “guess the square root of this trillion-digit number in your head and write it down”. Is it “just” kicking the can up a meta-level if I write down a square-root algorithm instead and prove that it is correct? By your argument all of CS is “just” kicking the can up a metalevel, and no progress has ever occurred in the field.

Eliezer answers:

I agree that the notion of meta-learning rather than hard-coding human preferences makes progress towards building an aligned Sovereign, and plausibly even towards meta-learning corrigibility (though that wasn’t the proposal here). A meta-learning rule that could correctly learn (and even extrapolate/idealize) all human preference, is almost-certainly much simpler than all of human preference or all of idealized human preference, in the sense of having lower algorithmic complexity. That doesn’t mean we know a meta-rule like that, or that the meta-rule we need is as simple as any loss function that could be written down in twenty lines of code. Any meta-rule that somebody tries to state in English will either be so ill-specified as to be meaningless, or I’ll be able to show how it kills you.

But the topic of the post is that if you build a meta-rule that, when updated off a human, learns a utility function that is not what you want, its metaness doesn’t help at all on corrigibility. The AI just goes and does the meta-learned thing you don’t want. It doesn’t help that the meta-utility-function had humans as a focus, or was putatively about a goal that humans would optimize for themselves if the AI let itself be shut down. It’s still the better course of action to extract all the tangled info from the humans, then go do that thing, sovereignly; it’s never the best course of action to let yourself be shut down. If you can state a perfect meta-rule, you end up with a perfect Sovereign, but it still doesn’t let you shut it down. So the structural metaness doesn’t yield progress on shutdownability.

Third, in the end the AI really would let itself be shut off, for the same reasons listed in the original paper. Stuart writes:

I don’t think it’s easy to understand the basic AG proposal without discussing Bayesian reasoning, beginning from some weak prior P_0(U) and gradually converging. At any given time t the AI’s distribution is P_t(U). If there were no possibility of gaining any further information, the AI could choose to maximize E_U[P_t(U)], the “mean” utility of the distribution, but in the general case the AI will choose cautious actions, ask permission, observe more, etc etc.

Notice that diagram B [in Figure 1] represents absolutely certain and absolutely incorrect knowledge about some of the black lines, which should never happen.

Eliezer responds:

The point at which the AI ceases exploring and starts exploiting is not when it becomes absolutely certain, but when it doesn’t expect it can gather further evidence to resolve its remaining uncertainty. It can also foresee this point coming in the future, and will act to defend itself now, knowing that in the future it will obtain all available evidence and then act.

And elsewhere, Stuart writes:

In the off-switch paper, the AI can do (1) action A, (2) announce action A and give the human of switching the AI off, or (3) switch itself off. WLOG, no matter what A is, the AI chooses (2) unless it is already certain what the human will decide, in which case it is indifferent between (1) and (2) (or, (3) and (2), if A looks really bad in expectation.

In MIRI’s example, action A is “do nothing, keep observing”. I can imagine circumstances where the AI isn’t certain that the human will allow this (e.g., if the AI is using scarce resources, blocking the train tracks, etc.) but if it is absolutely guaranteed to be harmless, what’s the issue? The argument stops working as soon as A is anything other than absolutely guaranteed to be harmless.

In conclusion , I don’t feel comfortable trying to adjudicate a debate between two people who both have so much of an expertise advantage over me. The most I’ll say is that their crux seems to be whether the AI could end up with an uncorrectably wrong model of the human utility function; if no, everything Stuart writes makes sense; if yes, everything Eliezer writes does. Stuart seems to agree that this is making convergence difficult:

I’m having a difficult time responding coherently because the MIRI argument simply seems to misunderstand the CHAI proposal and ends up saying the AI is 100% certain of a very bad U, which could only happen if you put in a prior saying that humans want the universe tiled with paperclips in one of three colors, and all other U have probability zero. This doesn’t seem to have much to do with the off-switch problem per se, except to repeat the basic idea that an AI with a fixed “known” U won’t want to be switched off.

btw, if we say that the prior does rule out the true U, but doesn’t rule out U’ which is 0.1% different, i.e., if the AI maximizes U’ the human gets at least 99.9% of the utility they would have received under maximization of U, that’s still probably way better than their own unaided efforts to achieve U*.

And Eliezer answers:

MIRI’s concern is that any rule that we or anybody knows how to state, updated off observations until the point where the AI doesn’t think it’s worth continuing to hunt down further observables entangled with the utility function (because information value has dropped below cost of information), will have its mean far away from true human values, such that maximizing the mean of this utility function will destroy all human value.

Somewhere in the Textbook From The Future there /might/ be a specification of a simple loss function and a methodology of training, such that, if you train that way, you get an AI that actually zeroes in on the human utility function… and then building a thing which maximized that meta utility function, would get you an aligned Sovereign. But still not a corrigible one, and if you missed a line of code from the Textbook, the resulting creation would not let you shut it down or edit that line of code back in.

You could argue that some particular meta utility function, that somebody knows how to state, is allegedly solution to the problem of creating an aligned Sovereign: just let this AI observe all the things, and it will update its meta utility function to do what we want. But even if this argument carried, and saved us all, it would not have solved corrigibility. It would have just solved the problem of an aligned Sovereign instead. That system, once booted, still wouldn’t let you edit the meta utility function.

This is as far as the discussion has gotten so far, but if either of them have a response to anything in this post or the comments to it, I’m happy to publish it (or signal-boost if it they post it as a comment here). Thanks to both of them for taking the time to try to help me understand their positions.