Contra Acemoglu On...Oh God, We're Doing This Again, Aren't We?

The Washington Post has published yet another “luminary in unrelated field discovers AI risk, pronounces it stupid” article. This time it’s Daron Acemoglu. I respect Daron Acemoglu and appreciate the many things I’ve learned from his work in economics. In particular, I respect him so much that I wish he would stop embarrassing himself by writing this kind of article (I feel the same way about Steven Pinker and Ted Chiang).

In service of this goal, I want to discuss the piece briefly. I’ll start with what I think is its main flaw, then nitpick a few other things:

1: The Main Flaw: “AI Is Dangerous Now, So It Can’t Be Dangerous Later”

This is the basic structure around which this article is written. It goes:

1. Some people say that AI might be dangerous in the future.

2. But AI is dangerous now!

3. So it can’t possibly be dangerous in the future.

4. QED!

I have no idea why Daron Acemoglu and every single other person who writes articles on AI for the popular media thinks this is such a knockdown argument. But here we are. He writes:

AI detractors have focused on the potential danger to human civilization from a super-intelligence if it were to run amok. Such warnings have been sounded by tech entrepreneurs Bill Gates and Elon Musk, physicist Stephen Hawking and leading AI researcher Stuart Russell.

We should indeed be afraid — not of what AI might become, but of what it is now.

Almost all of the progress in artificial intelligence to date has little to do with the imagined Artificial General Intelligence; instead, it has concentrated on narrow tasks. AI capabilities do not involve anything close to true reasoning. Still, the effects can be pernicious.

Then he goes on to talk about several ways in which existing narrow AI is pernicious, like potential technological unemployment or use by authoritarian states. Then, without any further discussion of superintelligence, he concludes:

The best way to reverse this trend is to recognize the tangible costs that AI is imposing right now — and stop worrying about evil super-intelligence.

I wonder if other fields have to deal with this. “People have said climate change could cause mass famine and global instability by 2100. But actually, climate change is contributing to hurricanes and wildfires right now! So obviously those alarmists are wrong and nobody needs to worry about future famine and global instability at all.”

Does Acemoglu argue this way when he writes about economics? “Some people warn of a coming economic collapse. But the Dow dropped 0.5% yesterday, which means that bad financial things are happening now. Therefore we should stop worrying about a future collapse.” This is not how I remember Acemoglu’s papers at all! I remember them being very careful and full of sober statistical analysis. But somehow when people wade into AI, this kind of reasoning becomes absolutely state of the art. There isn’t a single argument besides “AI does bad things now” in this entire article, but in the end it acts like it has disproven the conjecture that future superintelligent AI can be bad.

There’s no reason Acemoglu has to do this! It’s a bizarre own-goal! The responsible people on both sides have put so much work into trying to forge alliances and cross-pollinate their research programs. The highlight of this was probably the Asilomar Conference, where top “narrow AI has negative effects now” people and top “superintelligent AI is a big future risk” people got together and formulated a joint agenda expressing shared goals. I think this is more than just PR: controlling weak AI systems now is both important in its own right, and a trial run / strong foundation for controlling stronger AI systems in the future. For example, transparency and interpretability research can help us figure out how parole algorithms make their decisions, and can help future researchers figure out whether an AGI is concealing its real goal system from us. Short-term and long-term AI alignment issues are both important and naturally aligned, and there’s no reason why you have to put down one in order to hold up the other!

1.1: In Which I Hypocritically Put Down One In Order To Hold Up The Other

Despite that, I personally tend to put down a lot of the narrow AI risk research.

(I want to stress that I don’t represent the long-term AI risk movement, that the people who do are extremely concerned about present-day narrow AI risk and constantly offering it olive branches and alliances, and that this part is my personal bad opinions only)

I just…don’t find it convincing. Acemoglu says the “most ominous” effect of existing AI is its contribution to employment, and devotes most of the article to the damage this is supposedly causing. There are a lot of links involved, but if you follow them, none actually support his argument. The closest he gets is this paper, which he describes in the article as showing that “firms that increase their AI adoption by 1 percent reduce their hiring by approximately 1 percent”. But the paper itself is less convincing. It says that:

_Establishment-level estimates suggest that AI-exposed establishments are reducing hiring in non-AI positions as they expand AI hiring. However,we find no discernible relationship between AI exposure and employment or wage growth at the occupation or industry level, implying that AI is currently substituting for humans in a subset of tasks but it is not yet having detectable aggregate labor market consequences. _

I guess I can’t accuse Acemoglu of not reading the paper, given that he wrote it. Still, I think this result is pretty typical of the literature. Hanson and Scholl tried the same analysis and got the same result (paper, MR article). This has made me much more skeptical of a current AI unemployment problem than I was a few years ago.

I certainly don’t mean to assert that AI definitely won’t cause unemployment or underemployment (for my full position, see here). I think it probably will, sometime soon, and I support discussing policies - eg universal basic income - that will help us be ready for this eventuality. But I think humility would require Acemoglu to admit that as of yet there’s either no sign of this, or perhaps only the weakest trace of a signal. And that’s a uniquely bad match for Acemoglu’s main argument - that we are not allowed to worry about speculative future effects of AI because there are visible current effects. I mean, it’s bad enough to assert the nonsensical claim that AI can’t cause future problems because it causes present problems. But if you’re going to submit an article to the Washington Post on that basis, you should at least do an exceptionally good job establishing that there really are present problems. I’m not sure Acemoglu clears that bar.

For all the other stuff on algorithmic bias, destroying democracy, etc, please see Section IV of my review of Human Compatible here.

2: What Does It Mean To Call A New Technology Troubling?

Along with all this, Acemoglu does mention one thing I agree is real and extremely bad. That is:

And of course narrow AI is powering new monitoring technologies used by corporations and governments — as with the surveillance state that Uyghurs live under in China.

This is definitely happening, I am super against it, and I hope everyone else is too.

On the other hand, what about electricity? I am sure that electricity helps power the Chinese surveillance state. Probably the barbed wire fences on their concentration camps are electrified. Probably they use electric CCTVs to keep track of people, and electronic databases to organize their findings.

Any general purpose new technology makes lots of things more efficient. If you are an evildoer, you can use it to do evil more efficiently. Give an evildoer electricity, and they will invent electrified barbed-wire fences, electronic concentration camp records, and the electric chair (plus those loud stereos people sometimes play at 3 AM).

Electricity put lots of people out of work - I don’t see many lamplighters or hand weavers around anymore. Electricity “warps the public discourse of democracy”, with electrical-powered mass media - the radio, the TV, and now the Internet - all serving as vehicles for propaganda and misinformation during their time (heck, even the printing press did this). Everything the articles accuse AI of, they can convict some older technology of equally well.

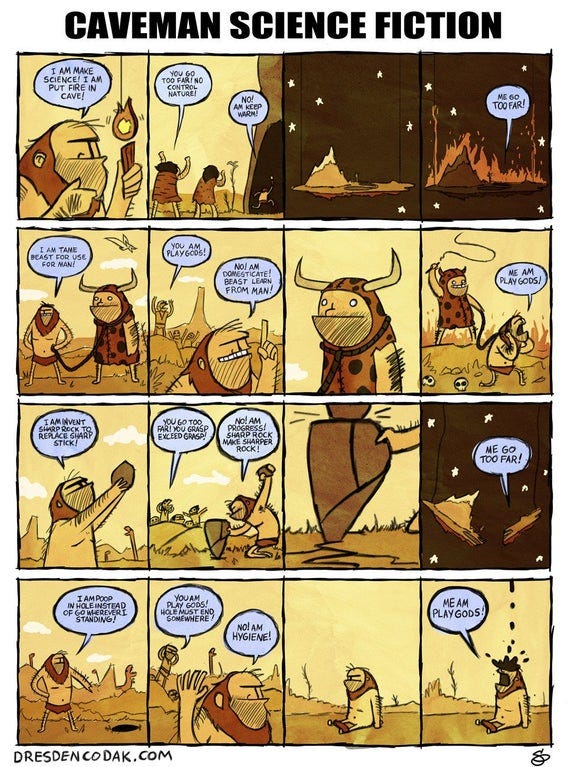

(source)

(source)

Does this mean the articles are bad and wrong? I’m not sure. Maybe a compromise position would be that all new technologies will have negative side effects, they’ll probably be worth it anyway, but we can at least keep this in mind and try to figure out if there are good ways to avert them. Acemoglu is just calling for “oversight from society and government to prevent misuses of the technology and to regulate its effects on the economy and democracy”, and for all I know, maybe this would have been a good idea with electricity too. It sounds reasonable enough to be almost platitudinous.

Still, a lot of platitudes are wrong, and I don’t think he puts nearly enough work into making his case. The printing press “warped public discourse” and “hampered the function” of the governments of its era. I’m sure the 16th-century Catholic Church would have loved the opportunity to exercise “oversight”, “prevent misuses” and “regulate its effects on the economy and democracy”. Would this have led to a better world? Also, exactly how is “oversight from society and government” going to prevent AI from being used by the Chinese surveillance state? Isn’t the Chinese surveillance state in some sense defined as everything having lots of oversight from society and government? I feel like parts of this may not have been fully thought through.

It could be that we consider all of these questions and decide on more oversight anyway, at least in those few and debatably-numbered countries where the good people are overseeing the bad people rather than vice versa. One might argue we did this a little with electricity; certainly we did it more with nuclear power. Is narrow AI more like the former or the latter? This is a question we’ve faced many times before, and I have no good general answer.

But the case for concern about superintelligent AI is fundamentally different. The problem isn’t just that it makes evildoing more efficient. It’s that it creates an entirely new class of actor, whose ethics we have only partial control over. Humans misusing technology is as old as dirt; technology misusing itself is a novel problem. If the technology is superintelligent and has the power to destroy the world, maybe it’s a really big problem. I am not saying everyone has to be concerned about this, but I think there’s a fundamental difference between this and all the other reasons to worry about AI, and that this difference makes it fair for some people to worry about it separately.

Conclusions

How do you write an entire article dismissing fear of superintelligent AI, which doesn’t contain a single argument against fear of superintelligent AI? Daron Acemoglu is a smart person and I doubt he did this by accident. I think he just didn’t care about the topic at all. He wanted space to make his argument that narrow AI is pernicious and that somebody needs to do something. Pitching it as “instead of worrying about superintelligence, worry about this!” seemed like a cute framing device that would probably get the article a few extra eyeballs.

Probably it delivered on the eyeballs, but I’m still super against this. Acemoglu accuses algorithms of warping our social media consumption and spreading misinformation to maximize clicks. I agree it would be good to stop this. But all the AI regulation in the world won’t help us unless we humans also resist the urge to spread misinformation to maximize clicks.

I think people treat jokes at the expense of the AI risk community as harmless because they seem like fringe weirdos. But somehow all these opinion writers always start their articles with a list of all the really impressive and trustworthy people who are deeply concerned about AI risk. Geniuses like Stephen Hawking. Top industrialists like Elon Musk. Leading AI researchers like Stuart Russell. Acemoglu name-drops all these people - then ignores them. I don’t understand why it’s so hard to make the jump from “extremely smart people and leading domain experts are terrified of this” to “maybe I should take this seriously enough to look into it for five minutes before dunking on it as a framing device for my real point”?

I would like Daron Acemoglu to stick to writing excellent papers that shed light on underappreciated problems and help lift countless people out of poverty - and to write fewer articles like this one. Everyone else could also stand to do a little better here.