Contra Hoel On Aristocratic Tutoring

I.

Erik Hoel has an interesting new essay, Why We Stopped Making Einsteins. It argues that an apparent decline in great minds is caused by the replacement of aristocratic tutoring by ordinary education.

Hoel worries we’re running out of geniuses:

Consider how rare true world-historic geniuses are now-a-days, and how different it was in the past. In “Where Have All the Great Books Gone?” Tanner Greer uses Oswald Spengler, the original chronicler of the decline of genius back in 1914, to point out our current genius downturn […]

There are a bunch of other analyses (really, laments) of a similar nature I could name, from Nature ’s “Scientific genius is extinct” to The New Statesman ’s “The fall of the intellectual” to The Chronicle of Higher Education ’s “Where have all the geniuses gone?” to Wired ’s” “The Difficulty of Discovery (Where Have All The Geniuses Gone?)” to philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel’s “Where are all the Fodors?” to my own lamentation on the lack of leading fiction writers.

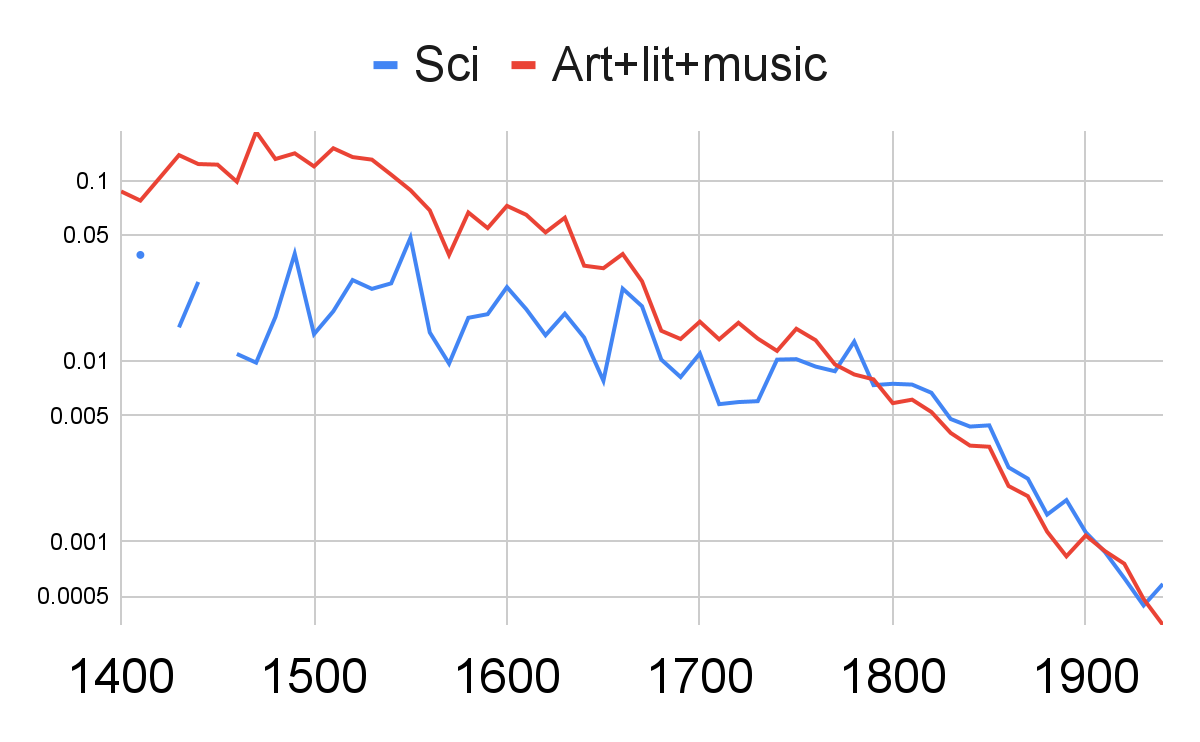

If you disagree, I’ll certainly admit that finding irrefutable evidence for a decline of genius is difficult—intellectual contributions are extremely hard to quantify, the definition of genius is always up for debate, and any discussion will necessarily elide all sorts of points and counterpoints. But the numbers, at least at first glance, seem to support the anecdotal. Here’s a chart from Cold Takes ’ “Where’s Today’s Beethoven?” Below, we can see the number of acclaimed scientists (in blue) and artists (in red), divided by the effective population (total human population with the education and access to contribute to these fields).

He argues the most likely cause is the decline of “aristocratic tutoring” - an educational method typical among the ultra-rich of the past - and its replacement with normal public (or private) schools.

The answer must lie in education somewhere […] paradoxically there exists an agreed-upon and specific answer to the single best way to educate children, a way that has clear, obvious, and strong effects. The problem is that this answer is unacceptable. The superior method of education is deeply unfair and privileges those at the very top of the socioeconomic ladder. It’s an answer that was well-known historically, and is also observed by education researchers today: tutoring.

[…]

Let us call [the] past form aristocratic tutoring , to distinguish it from a tutor you meet in a coffeeshop to go over SAT math problems while the clock ticks down. It’s also different than “tiger parenting,” which is specifically focused around the resume padding that’s needed for kids to meet the impossible requirements for high-tier colleges. Aristocratic tutoring was not focused on measurables. Historically, it usually involved a paid adult tutor, who was an expert in the field, spending significant time with a young child or teenager, instructing them but also engaging them in discussions, often in a live-in capacity, fostering both knowledge but also engagement with intellectual subjects and fields.

He amply proves that many of the great geniuses of the past, including Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, and John von Neumann received tutoring like this, and suggests that its absence (more because of strengthening democratic norms than because people don’t have the money) might be why we don’t see figures of their stature anymore.

II.

I agree that this kind of tutoring sounds great. I wouldn’t be surprised if it has a big effect size. But it’s not the reason we have fewer geniuses.

Why not? Suppose that half of past geniuses were tutored this way, and half weren’t. Even if every single genius who was tutored owed his genius entirely to the tutoring, the tutoring could only explain half of geniuses. That means that after the tutoring stopped, we would expect half as many geniuses. But Hoel is making a stronger claim: that there are almost no geniuses today. For aristocratic tutoring to explain that, we would need for almost all past geniuses to be aristocratically tutored. But as far as I can tell, that isn’t true. Probably well below half of them were. Just to give some examples:

Isaac Newton went to a local school at at 12, and to Cambridge at 17. The Wikipedia page on his early life doesn’t mention “tutor”, except in the context of a college teacher. His adopted father was a country parson, and his family wasn’t rich enough to do aristocratic tutoring even if they’d wanted to. Articles on his early life stress his self-motivated nature: he was constantly building things and observing things on his own time.

Wolfgang Mozart was tutored, but primarily by his father, himself an excellent violinist. According to his Wikipedia article, “In his early years, Wolfgang’s father was his only teacher”. Mozart was already an obvious child prodigy by 6 or 7, and wrote his first symphony at 8. I can’t find any evidence that non-family members contributed to his education. This kind of tutoring is still common; my wife learned cello from her grandmother, a professional music tutor.

Charles Darwin went to a local school at age 8, switched to a boarding school at 9, spent a summer at age 16 following his father (a doctor) around as he treated patients, then went to medical school. He switched to regular college at Cambridge at 19, where he seemed to have a pretty traditional education. Wikipedia has a long article on his education, which doesn’t mention the word “tutor” until college age, when he “spent the autumn term at home studying Greek with a tutor”. Later in college, he “joined other Cambridge friends on a three-month “reading party” at Barmouth on the coast of Wales to revise their studies with private tutors”. I don’t think he had a stronger relationship with being tutored himself, especially not in childhood. His summer following his father around learning medicine was probably good for him, but not outside the bounds of what still happens today (I followed my father around learning medicine).

Louis Pasteur was born “to a Catholic family of a poor tanner”. He went to primary school at 8 and college at 16. I can’t find any evidence he was tutored.

Charles Dickens barely seems to have been educated at all. His family was so poor that he spent some of his childhood working in a sweatshop. During other periods they did a little better and he went to small lower-to-middle-class private schools. Dickens seems to have gotten most of his education by reading novels on his own.

Thomas Edison grew up poor in Michigan. Again according to Wikipedia, “Edison was taught reading, writing, and arithmetic by his mother, who used to be a school teacher. He attended school for only a few months. However, one biographer described him as a very curious child who learned most things by reading on his own. As a child, he became fascinated with technology and spent hours working on experiments at home.”

Hoel argues that the decline in aristocratic tutoring is “why we stopped making Einsteins”. But then why did we stop making Newtons, Mozarts, Darwins, Pasteurs, Dickenses, and Edisons?

III.

One other argument: Hoel cites Holden Karnofsky’s Where’s Today’s Beethoven?, which suggests that music is a typical case of the genius decline.

But aristocratic tutoring in music is alive and well. When my brother was identified as a piano prodigy, my (well-off but not absurdly rich) parents hired jazz musician Linda Martinez to tutor him. I asked around and this is apparently pretty common in music. In fact, it seems common across a variety of fields, especially those that aren’t taught in school and where success doesn’t make you too rich to need tutoring money (a friend brings up chess as another example).

If aristocratic tutoring were a significant factor behind declining genius, we would expect to see a split: fields like science where tutoring is rare would lose their geniuses, whereas fields like music where tutoring is common would be as genius-filled as ever. But people use music as a typical example of a declining-genius field. So that can’t be it.

IV.

So what’s my explanation? You will not be surprised to hear it’s the maximally boring one, a combination of:

-

Good ideas are getting harder to find. In 300 BC, if you noticed that the water level in your bathtub got higher when you got into it, you were allowed to run through the streets shouting “eureka!” and declare yourself to be a genius. Now you would need some 400 page mathematical proof drawing on the topology of eight-dimensional manifolds in order to get that kind of cred.

-

We’re finding lots of ideas anyway, but only by dectupling the number of researchers. More researchers means more distributed progress: it’s unlikely one person will stumble across a fully formed brilliant theory before other people have nibbled off bits and pieces of the same idea.

-

More democratic norms / tall poppy syndrome . In the past, people celebrated geniuses and would play up their accomplishments in order to have someone to celebrate. Now it’s considered kind of cringe to believe in geniuses, and you should play down their accomplishments, play up the degree to which they depended on lab assistants / collaborators / support staff, and maybe even accuse them of hogging glory or “crowding out” others in the field.

AI seems to have its share of geniuses: for example, people seem very impressed with Geoff Hinton. And AI alignment - the subfield I’m most familiar with, so new and small that it’s controversial whether it should be considered a science at all - is absolutely full of geniuses. I mean, I can’t assess whether they’re right about anything, I just mean that there are a couple of individuals who have developed entire new paradigms, who are widely acknowledged as way above the rest of the field, and who everyone expects the next interesting result to come from.

If people are still working on AI a hundred years from now, I expect them to talk about Hinton in the same way biologists talk about Darwin now. If they’re still working on alignment (which would be profoundly weird for many reasons) I expect them to talk about Bostrom and various other people I won’t name because some of them read this blog and don’t need bigger egos.

I think this is because AI is new and small(-ish), and AI alignment is very new and very small.

Since it’s new, good ideas aren’t hard to find. I mean, they’re still hard enough that you or I can’t find them. But not so hard that the smartest people in the world can’t still luck out and open up entirely new vistas.

Since it’s small, if one of the smartest people in the world does go into AI alignment, they stand out - unlike physics, which is so full of the smartest people in the world that nobody notices another one.

I’ll give one even weirder example. A few years ago, I wrote a very political post, called Can Things Be Both Popular And Silenced? It touched on “guru” culture in politically incorrect discourse - the phenomenon of people like Jordan Peterson who became really famous by saying controversial things - and it asked: why aren’t there equally famous figures on the left? The social justice community is an order of magnitude bigger than the intellectual dark web, so how come it hasn’t produced proportionately greater celebrities? Ibram X Kendi, maybe. Ta-Nehisi Coates, ten years ago. But how come they aren’t bigger and more numerous.

The answer is: they were, we just need to look further back. The titans of black anti-racism are Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, both most active in the 60s. The titan of Hispanic anti-racism is Cesar Chavez - also the 60s. The titan of gay rights is Harvey Milk - now we’re up to the 70s. Ask someone who isn’t an expert on feminism to name famous feminists, and you’ll probably get people like Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, and Andrea Dworkin - 70s again. I’m not sure any modern black, gay, or feminist activists measure up to these people in terms of influence, which is fine: the modern paradigm of minority rights began around the 60s and 70s, the first few people to operate within it got outsized acclaim, and there’s no easy way to equal them now.

I think everything is like this: easy to stand out in when you’re small and new, harder when you’re big and old. I realize biology was several thousand years old in wall clock time by Darwin’s era, but I think it’s entirely possible that it was newer than AI is now in terms of researcher-lifetimes-spent and especially in terms of quality-adjusted researcher-lifetimes spent (a researcher with access to the Internet might be several QARLs comared to a researcher who has to sail to Alexandria to consult the Great Library).

So I think efforts like Hoel’s to find the One Thing That Went Wrong in producing geniuses are doomed to fail. But even if I’m wrong, aristocratic tutoring isn’t that One Thing: there are too many counterexamples.