Contra Kriss On Nerds And Hipsters

Sam Kriss has a post on nerds and hipsters. I think he gets the hipsters right, but bungles the nerds.

Hipsters, he says, are an information sorting algorithm. They discover things, then place them on the altar of Fame so everyone else can enjoy them. Before the Beatles were so canonical that they were impossible to miss, someone had to go to some dingy bar in Liverpool, think “Hey, these guys are really good”, and report that fact somewhere everyone else could see it.

So someone has to be the sort of person who goes to dingy bars in Liverpool, listens to the music there, and has strong public opinions about it. In theory this could be you or me, just so happening to live in Liverpool, just so happening to drink in dingy bars, just so happening to notice the Beatles, and just so happening to be in the right place to report about them. In practice it’s easier for there to be some type of person who optimizes for this and builds his whole identity around how he consumes obscure art that hasn’t been discovered yet, then forms opinions on it.

Others have already written about how nonconformists - people who do the valuable service of telling us when the emperor has no clothes - have their valor stolen by fake nonconformists - people who parrot an established narrative corresponding to what everybody knows nonconformism is supposed to sound like. In the same way, hipsters had their valor stolen by fake hipsters - people who drank Pabst Blue Ribbon because everyone knows that’s what the people who discover things are supposed to discover. Still, the real hipsters had been doing a useful service.

Then they all died off. Hipsters were part of society’s information sorting algorithm. But now we have literal algorithms, the ones on YouTube and Spotify. They sort our information fine.

This was Kriss on hipsters. I appreciated this perspective and can’t unsee it. Then he moves on to nerds.

Kriss defines nerds as “someone who likes things that aren’t good”. More specifically, someone who is an obsessive (counting, itemizing, collecting) fan of something bad. Kriss doesn’t define “bad”, but it’s fine - the rest of the post will be entirely about the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Most of his examples of bad things are popular, and he sort of equivocates between liking bad things full stop and liking bad things that are popular in order to go along with the herd.

I had always heard “nerd” used to mean “person who liked math, computers, and maybe RPGs” and “geek” to mean “someone who liked Doctor Who and (later) the Marvel Cinematic Universe”. Bill Gates is the ultimate nerd, but he’s probably too busy making money to have strong opinions on the media. Still, surely CTRL+H-ing every mention of “nerds” in Kriss’ post to read “geeks” would be a simple friendly amendment.

The bigger problem is that it still feels mysterious. Someone obsessively liking bad things? Why?

Also, I notice that by this definition all sports fans must be nerds. Sports is certainly bad: it’s a bunch of sweaty adult men freaking out about who has a ball for two hours, for several hundred almost-identical episodes per season. And man, do people obsess over it. The most knowledgeable RPG geek who owns all the expansion books cannot match the fervor of the sports fan who has memorized the RBIs and ERAs of every player in the league and has all their rookie cards and goes to every game. But aren’t nerds and “sportsball fans” natural enemies?

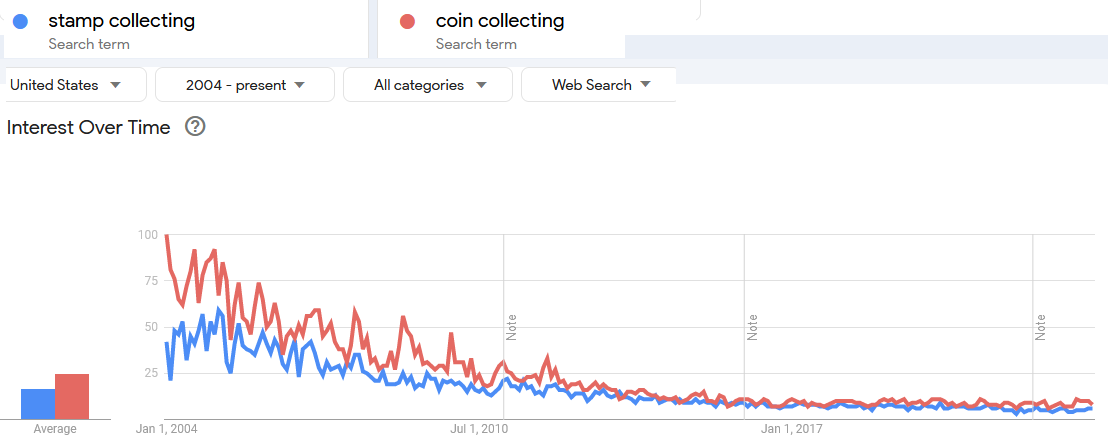

Also, speaking of collectors, are there any, any more? When I was a child, the stamp collector and coin collector were stock cultural figures. Now I realize I haven’t thought about them in years. Where did they go?

My theory is: hipsterism and nerdism are both forms of trying to invest your identity in a cultural product. If there’s no competition, you become a hipster; if there’s high competition, you become a nerd.

By “invest your identity in a cultural product”, I mean - sometimes you experience some work of art (broadly defined) and it’s really good. Either it’s really good full stop, or it exactly corresponds to your own personal values and how you want other people to perceive you. Sometimes it’s so good that it feels almost painful that the author wrote it and you didn’t. It feels like there ought to be some way to rectify this error, to gain status by basking in the reflected light of its glory.

For the hipster, this is easy. They have discovered the thing in a dingy bar in Liverpool, so they announce it to the world, and gain credit as the astute taste-having discoverer of X. Even the mildly hip can benefit from this. I wasn’t the first person in the world to discover George R. R. Martin’s books, but I was the first person in my friend group. I recommended them to my friends, and when my friends also liked them, they were grateful to me and I got some mild credit for discovering good books. And if someone else in my friend group liked them, he could bring them to his other friend groups and probably be the first person to advertise them there.

As long as the thing is obscure, you’re fine. It doesn’t have to be hipster-obscure. Sam Kriss makes a self-deprecating joke about how his obsession with medieval mysticism is totally different than nerdery. I think he’s right; not that many people care about medieval mysticism, so Sam Kriss can be “that medieval mysticism guy” without facing too much competition.

When does this fail? When it’s the f@#king Marvel Cinematic Universe. Or Star Wars. Or the New York Yankees. Or anything else where the whole point is that every single person in the world is already aware of and consuming the thing. How do you get a reputation as (an identity as?) “the Star Wars guy”? Certainly not by going around and saying “Hey, have you seen Star Wars yet?”. We have. Not even by saying “Hey, Star Wars is really good!” Everyone knows this, it would be like praising sex, or pizza. But the guy who has figurines of every minor character with two seconds of screentime and has read all 2,000 Extended Universe books and is fluent in Wookie - that’s “the Star Wars guy”.

So in this model, hipsters identify with a product based on breadth - they’ve found something first. Nerds identity based on depth - they’ve proven they “care about” a universally-known product more than anyone else, by “outcompeting” everyone else in the level of devotion they show it.

Is this bad? I don’t want to say you should never build identity around liking a thing. Most non-enlightened people want to have some distinguishing characteristic, and anything you do - care about a hobby, or a skill, or a political cause - is going to feel kind of cringe. Caring about a piece of art seems no worse than anything else. I personally named my house and business after Silmarillion references - I would have named my car after one, but I learned my friend had named her car after it first, and that Steven Colbert had also named his car after it, and it would be weird to have all these cars named “Vingilótë” driving around. At this point I backed off.

Still, despite apparently being basic, I notice I would die before naming something important after something from the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Can I justify this? Partly it’s that I don’t really like the MCU, so I don’t want to identify with it anyway. But even if I did like it, I have the same feeling that I’d rather die. Is it because it’s too popular? That there are too many people (like Sam Kriss) going around criticizing it? Or is it just that Marvel feels optimized to make you like it and buy action figures, and liking it and buying action figures would make me feel like a little puppet being jerked back and forth by the Disney Corporation?

Also, what was up with stamp and coin collectors? This seems like a different phenomenon: surely nobody wanted to identify with the US Postal Service. I have a better hypothesis for why this pastime has died out: collectors enjoyed the thrill of hunting for a rare piece, but Amazon and eBay have made it trivial to exchange money for whatever coins/stamps you want. I’m not sure this works; when I was young in the 90s, there was a store in my hometown that sold rare coins; even then I could have gone to the store and walked out with a pretty good collection. But maybe the fact that I would need multiple books to know which coins were “rare”, and that the store could have been out of one or two valuable pieces, was enough cover to make it still seem interesting and impressive. Now there’s no sense that you have to really care about stamps or coins to have a great stamp/coin collection: you just need a higher budget than whoever else typed “stamps and coins” into the eBay search function.