Contra Resident Contrarian On Unfalsifiable Internal States

I. Contra Resident Contrarian . . .

Resident Contrarian writes On Unfalsifiable Internal States, where he defends his skepticism of jhana and other widely-claimed hard-to-falsify internal states. It’s long, but I’ll quote a part that seemed especially important to me:

I don’t really want to do the part of this article that’s about how it’s reasonable to doubt people in some contexts. But to get to the part I want to talk about, I sort of have to.

There is a thriving community of people pretending to have a bunch of multiple personalities on TikTok. They are (they say) composed of many quirky little somebodies, complete with different fun backstories. They get millions of views talking about how great life is when lived as multiples, and yet almost everyone who encounters these videos in the wild goes “What the hell is this? Who pretends about this kind of stuff?”

There’s an internet community of people, mostly young women, who pretend to be sick. They call themselves Spoonies; it’s a name derived from the idea that physically and mentally well people have unlimited “spoons”, or mental/physical resources they use to deal with their day. Spoonies are claiming to have fewer spoons, but also en masse have undiagnosable illnesses. They trade tips on how to force their doctors to give them diagnoses:

> In a TikTok video, a woman with over 30,000 followers offers advice on how to lie to your doctor. “If you have learned to eat salt and follow internet instructions and buy compression socks and squeeze your thighs before you stand up to not faint…and you would faint without those things, go into that appointment and tell them you faint.” Translation: You know your body best. And if twisting the facts (like saying you faint when you don’t) will get you what you want (a diagnosis, meds), then go for it. One commenter added, “I tell docs I’m adopted. They’ll order every test under the sun”—because adoption means there may be no family history to help with diagnoses.

And doctors note being able to sort of track when particular versions of illnesses get flavor-of-the-week status:

> Over the pandemic, neurologists across the globe noticed a sharp uptick in teen girls with tics, according to a report in the Wall Street Journal. Many at one clinic in Chicago were exhibiting the same tic: uncontrollably blurting out the word “beans.” It turned out the teens were taking after a popular British TikToker with over 15 million followers. The neurologist who discovered the “beans” thread, Dr. Caroline Olvera at Rush University Medical Center, declined to speak with me—because of “the negativity that can come from the TikTok community,” according to a university spokesperson.

Almost no one who encounters them assumes they are actually sick.

Are there individuals in each of these communities that are “for real”? Probably, especially in the case of the Spoonies; undiagnosed or undiagnosable illnesses are a real thing. Are most of them legitimate? The answer seems to be a pretty clear “no”.

I’m not bringing them up to bully them; I suspect that there are profiteers and villains in both communities, but there’s also going to be a lot of people driven to it as a form of coping with something else, like how we used to regard cutting and similar forms of self-harm. And, you know, a spectrum of people in between those two poles, like you’d expect with nearly anything.

But it’s relevant to bring up because there seem to be far more Spoonies and DID TikTok-fad folks than people who say they orgasm looking at blankets because they did some hard thinking (or non-thinking) earlier. So when Scott says something that boils down to “this is credible, because a lot of people say they experience this”, I have to mention that there’s groups that say they experience a lot of stuff in just the same way that basically nobody believes is experiencing anything close to what they say they are.

Granting that this is not the part of the article RC wants to write, he starts by bringing up “spoonies” and people with multiple personalities as people who it’s reasonable to doubt. I want to go over both cases before responding to the broader point.

II. . . . On Spoonies

“Spoonies” are people with unexplained medical symptoms. RC says he thinks a few may be for real, but most aren’t. I have the opposite impression. Certainly RC’s examples don’t prove what he thinks they prove. He brings up one TikToker’s advice:

In a TikTok video, a woman with over 30,000 followers offers advice on how to lie to your doctor. “If you have learned to eat salt and follow internet instructions and buy compression socks and squeeze your thighs before you stand up to not faint…and you would faint without those things, go into that appointment and tell them you faint.”

Translation: You know your body best. And if twisting the facts (like saying you faint when you don’t) will get you what you want (a diagnosis, meds), then go for it. One commenter added, “I tell docs I’m adopted. They’ll order every test under the sun”—because adoption means there may be no family history to help with diagnoses.

This person is using a deliberately eye-catching title (Lies To Tell Your Doctor) to get clicks. But if you read what they’re saying, it’s reasonable and honest! They’re saying “If you used to faint all the time, and then after making a bunch of difficult lifestyle changes you can now mostly avoid fainting, and your doctor asks ‘do you have a fainting problem yes/no’, answer yes!” THIS IS GOOD ADVICE.

Imagine that one day you wake up and suddenly you have terrible leg pain whenever you walk. So you mostly don’t walk anywhere. Or if you do have to walk, you use crutches and go very slowly, because then it doesn’t hurt. And given all of this, you don’t experience leg pain. If you tell your doctor “I have leg pain”, are you lying ?

You might think this weird situation would never come up - surely the patient would just explain the whole situation clearly? One reason it might come up is that all this is being done on a form - “check the appropriate box, do you faint yes/no?”. Another reason it might come up is that a nurse or someone takes your history and they check off boxes on a form. Another reason it might come up is that everything about medical communication is inexplicably terrible; this is why you spend umptillion hours in med school learning “history taking” instead of just saying “please tell me all relevant information, one rational human being to another”.

I’ve personally suggested that patients lie like this. My Guide To Navigating The Inpatient Mental Health System includes a section for people who are scared that a new psychiatrist who they don’t know well enough to trust might commit them if they mention suicidal thoughts. I wrote:

If you don’t [have suicidal thoughts], then say you don’t. If you mostly don’t but you are some sort of chronically indecisive person who has trouble giving a straight answer to a question, now is the time to suppress that tendency and just say that you don’t. If you do, but you would never commit suicide and it’s not a big part of why you’re seeing them and you don’t mind lying, you can probably just say you don’t.

I still stand by this suggestion. 99% of psychiatrists aren’t dumb enough to commit someone who has the occasional suicidal thought but would never act on it - but if you work in a mental hospital, you quickly become acquainted with the 1% exceptions.

Telling doctors that you’re adopted in order to get genetic tests seems more genuinely deceptive and counterproductive. But it seems like the sort of deception that you would come up with if you were suffering a lot and wanted to maximize chances of your doctor figuring out why, without really understanding how genetic tests worked.

But based on a few circumstantial things like these, people keep tarring all “spoonies” as fakers. I had a patient like this recently. They had some weird symptoms that pattern-matched to “the type of thing someone might make up”, the two or three most common tests didn’t find anything, a succession of doctors accused them of making the symptoms up, and they had absolutely awful quality of life for a year or two. Finally some doctor (not me, I was their psychiatrist) dug a little deeper and found a tumor the size of a tennis ball, removal of which relieved all of their symptoms.

Are all spoonies like this? No. My totally made-up wild guess, which might be completely wrong, is that about 20% have some physical illness we understand perfectly well (like a tumor) that just hasn’t been detected yet, 30% have some physical illness we haven’t discovered/characterized/understood yet, 45% have some psychosomatic condition, and 5% are consciously faking for attention. I’m making up random numbers on a question that’s deeply important to many people, and I’m sorry if fifty years from now we learn these were totally wrong.

Regarding the 45% with psychosomatic conditions, here’s a quick philosophy-of-mind lecture on perception which I promise will be relevant.

All perception is, in a sense, hallucination. That is, you never see anything directly. When you see a tree (to be extremely pedantic) the tree doesn’t enter your head. What you’re seeing is photons that have bounced off the tree, hit your retina, gotten converted into electrical impulses, been shuffled between a few brain regions with names like “superior colliculus” and “thalamus”, gotten converted into different electrical impulses, and finally sent in a nice package to the little homunculus who lives in your neocortex. So one (extremely pedantic) claim about perception is that the only thing the little homunculus ever perceives directly is nerve impulses from the thalamus. The sight of the most beautiful flower you’ve ever seen is just a pattern of nerve impulses from the thalamus. The most horrifying pain you have ever experienced is just a pattern of nerve impulses from the thalamus. This is slightly false - don’t get angry that I’ve described the brain circuitry slightly incorrectly - but it’s true enough for our purposes.

What do we mean when we say that a certain perception (let’s say of Jesus) is a “hallucination”? We don’t mean anything about the experience the little homunculus in your neocortex is having. We mean that this particular pattern of nerve impulses from the thalamus - which is the same either way - doesn’t correspond to a referent in the external world. Maybe in 30 AD, St. Peter’s thalamus sent his neocortex the packet 3a09e1508ff7, which corresponded to some particular image of Jesus, and this wasn’t a hallucination because Jesus was standing right in front of him. And maybe last week in a mental hospital in Ypsilanti some schizophrenic’s thalamus sent his neocortex that exact same packet, 3a09e1508ff7, which corresponds to the exact same perception of a vision of Jesus , but in that case it was a hallucination, because Jesus wasn’t there.

(source: I lucid dream sometimes, and instead of flying or having wild sex I mostly just observe the qualities of my hallucinatory experience in great detail, especially how realistic it is, in the hopes that I’ll remember it when I wake up. But I also sometimes talk to patients with actual hallucinations and they say this too)

The reason I’m hammering this in is that psychosomatic pain is actual pain. Somebody whose knee just got crushed by an anvil has their thalamus send their neocortex packet 09f7e8e15445, which corresponds to the qualia of excruciating pain in their knee. Someone with psychosomatic knee pain gets that same packet from the thalamus, packet 09f7e8e15445, and feels the exact same qualia.

(source: no source for the thalamus in particular, I’m probably wrong about that. But the reason I think psychosomatic pain is painful is I’ve talked to a lot of chronic pain patients and they seem pretty insistent on this. I guess they could all be lying, but one of them later committed suicide, and I can’t explain why they would do that if it was a con. See also my review of Unlearn Your Pain. Also, the existence of phantom limb pain requires something like this view.)

If a witch cursed you with either a physical pain condition or a psychosomatic pain condition, but let you choose, the wrong answer is “obviously the psychosomatic pain condition, that one’s fake so it should be fine”. The right answer is to ask something like “which one is easier to treat?” or “which one is more likely to go away on its own?” or “which one am I more likely to get sympathy and support for?”

And so on to fatigue and nausea and gastrointestinal issues and all of the other psychosomatic symptoms. This is a subtle point. But it’s a subtle point you should get right. I’ve seen children get traumatized and hate their parents for getting it wrong, doctors get sued and patients kill themselves for getting it wrong; we talk about lots of purely academic things here, but getting this point wrong can very easily ruin your life.

This isn’t to say that you can’t come up with some strategy for blaming victims or The Broader Culture or whatever for these symptoms if you really want. I’ve written before about anorexia, which really does seem to involve cultural expectations for someone to get thin, start with a desire to be thin, and then some biological switch gets flipped and they are unable to eat whether they want to or not. These people aren’t making it up and their qualia of fullness and revulsion at the thought of eating food are exactly like my qualia when I have eaten eight slices of bread in a row and everyone is staring at me and I suddenly realize I am a disgusting pig. There is some sort of extremely complicated biology x personality x culture interaction that starts the process, which explains why anorexia is much more common in cultures where it is widely recognized and where people hold awareness-boosting campaigns about it. The same seems to be true of chronic pain and all sorts of other things. I still don’t have a great model for this, although predictive coding is a mediocre model of some of it. I’m just really convinced that these people are reporting their internal states accurately. I have trouble thinking of any metaphor to hammer home how strong a degree I believe this, other than the “thalamus sending packets to the homunculus” one.

I think this is a more productive lens to use for “spoonies” than “look! here are people who are faking stuff!” Also, everyone on TikTok is terrible and shouldn’t be considered a representative of their respective communities.

III. . . . On Dissociative Identity Disorder

What about multiple personality?

I have at least three acquaintances who are in the category RC talks about - people who say they have some sort of multiple personality type thing going on, that it’s fine, they live with it, it’s no big problem.

(I originally would have said I had two such acquaintances, but when I was talking about this post with someone who had never mentioned it to me before, they admitted they also did this. I think this is an argument against people only doing it for attention.)

One of these people is an Ivy League STEM PhD student. Another has an important professional upper-class job I can’t give more information about without doxxing them. Each of their stories is slightly different, but there are common threads. All of them were part of the same fiction/role-playing community. Some of them are downstream of others - eg after the first person in the community had the experience with multiple personalities, they talked openly about it and got other people interested. All of them are high-functioning and describe it as a neutral-to-positive experience.

Beyond that, the stories are all slightly different, but smoothing them into a single thread: the person got really into some piece of fiction, and found that one of the characters they were modeling really carefully was now “active” in some sense where could give them advice. For example, the person might be kind of a pushover, and then one time after they watched Star Wars ten times in a row, someone bossed them around particularly badly, and they imagined Darth Vader telling them to give into their anger and fight back (this is a fake example, there isn’t someone with a Darth Vader personality running around). Then this became a sufficiently regular occurrence that they could query their “Darth Vader” module and get good advice on social situations that their normal personality wouldn’t give them. Or maybe they would have a Darth Vader monologue running at the same time as their regular monologue, giving different advice. Eventually their inner Darth Vader absorbed various aspects repressed from their regular personality and became a different person from movie-Vader, more fleshed-out and focused on their particular concerns. They emphasize that it really feels like Vader is in their head giving them advice, or that they sometimes “become” Vader - and in particular they emphasize that this is different from just asking themselves “what would Darth Vader do in this situation?”. They understand that most people learning about their situation would expect that they’re exaggerating a much more boring “just ask yourself what Vader would do” situation, and they’re fine with people believing that if they want, but insist that it’s actually something different and more interesting than that.

(I want to repeat that Darth Vader is a fake example - but it does tend to be characters who are very different from their usual personality, and 2/3 of them say the most striking example of this was with an evil character)

In most of the cases I know about, there was some deliberate attempt to cultivate the alternate personality, in the context of other people in the community telling them this might happen and was interesting. A skeptic could seize on this “Aha! I knew it was just people trying to be quirky!” But in the stories these people told me, it was more about - they found that this effort was producing something unexpected, and developing new personality aspects that they needed, so they kept going. If you take one step towards Darth Vader, he will take two steps toward you (sorry if I am sounding like a Sith youth pastor).

I find this all pretty believable for a few reasons. Lots of people (Buddhists, philosophers, psychologists) talk about how the ego is an illusion. And if you’re going to have an illusion, it doesn’t seem significantly weirder to have two illusions. Reading Origin Of Consciousness In The Breakdown Of The Bicameral Mind (see my review here) convinced me that all theories of mind are made up, that different cultures make up their theories of mind differently, and that theories of mind which separate the ego and superego and whatever into different entities aren’t inherently dumber or harder to work with than theories which count them all as the same entity.

I don’t recommend having multiple personalities, and I’m careful to stay away from this sort of thing myself. All of the people who take psychotherapy seriously say it’s important to have a well-integrated personality, and splitting off parts of your personality sounds like the opposite of that. If, as Jaynes hypothesizes, the ancients’ relationship to their deities was similar to a modern DID patient’s relationship to their alters, then the most important commandment of my ancestral religion is to STOP DOING THAT, and although I am not a religious Jew I am at least willing to listen to that particular Chesterton’s Fence.

Still, I think of this as inadvisable, not impossible.

IV. . . . On Identifying Liars

RC goes on to use these two cases as proof that sometimes large groups of people lie, even if they don’t seem to have much motivation:

The why-would-they-lie argument doesn’t hold water; you can point to countless groups who conveyed information that was false as a group. You can see the obvious falseness mixed into Spoonieism and DID TikTok fads.

…and then makes an argument I find pretty bizarre. He quotes a Douglas Adams piece on how predicting the trajectory of a baseball seems to require advanced physics, but many children and ignorant people can do it anyway by instinct, then concludes:

It is not a secret that people who trend towards rationalism (or tech, with which rationalism has significant overlap) are not, on average, considered to be exceptionally socially skilled. A placement on the autism spectrum or some other form of neurodivergence is considered to be the norm rather than the exception to the rule amongst them. I don’t think this is bad; if anything, it’s where the group’s value comes from in the first place.

But with that comes a group-wide expectation that things that can’t be quantified with math are thus default-unknowable. A statement like “I could tell he was lying” isn’t quite taboo nonsense there, but it carries much less weight than in other places. People are less able or less willing to point out that someone looks less credible for socially understood reasons than in other less-enlightened-more-practical contexts.

Sometimes this is nice, but at some extremes, it ends up being a lot like if someone looked at [Douglas Adams’] description of a person catching a baseball above, realized that they can’t really explain how that happens, and then concluded that baseball catching was not a skill that does or could exist.

At the extremes of those extremes, you see things like the jhana thing: where it’s something that seems unlikely to most but is unfalsifiable, and because of that unfalsifiability is then assumed to be true because it was claimed at all.__ By Scott’s standard above, we would basically assume that any claim we couldn’t disprove was true, provided we could find at least a few thousand people who claimed it.

This sounds like: “I, RC, have the mysterious mental ability to detect liars. I admit I can’t prove this, but come on, you should probably just trust me because it’s perfectly reasonable to think other people have mysterious mental abilities you don’t.”

But that’s the exact point he’s been arguing against this whole time! Either we trust trustworthy-sounding people who we like, when they say stuff that sounds kind of plausible - or we apply extreme skepticism about every not-immediately-verifiable claim!

The evidence for jhanas is thousands of people over thousands of years saying they’ve experienced it, a bunch of my friends who I trust a lot saying it worked for them, a handful of experiments with EEGs that seem to show positive results, and a promise that if I tried hard enough I could replicate the results. The evidence for Resident Contrarian being especially good at detecting lies is he says so.

I don’t think RC is lying. I think he has the internal experience of seeing some people say weird stuff, and feeling sure that those people are lying. Probably most times he felt this way, the people were lying, because lots of heuristics almost always work. On the other hand, my lie detector - which also usually works - gets different results from his in this case. It’s perfectly fine if we want to go our different ways and believe our respective intuitive lie detectors. But if we’re going to try to come to debate the issue publicly, I think we need more than just “well my lie detector says X”. We have to do something in between reasoning it out, or at least sharing the data we used to train our lie detectors.

V. . . . On What The Prior Should Be

So here’s the training data that got me to this point:

-

Francis Galton did a bunch of research on visual imagination, ie the ability to picture something in your “mind’s eye”. He found that this ranged from people who didn’t have this at all, to people with “eidetic imagery”, eg exactly as vivid as the real world - and psychologists have since confirmed this through various clever experiments. He also found that the people who didn’t have visual imagination at all thought that all the references to “seeing things in your mind’s eye” in the language and culture were just kind of metaphorical, and nobody could actually do that. When he tried to convince them that lots of people could, they were skeptical! They didn’t believe that other people could be having this weird internal experience which was impossible for them. I think this was wrong (I have some visual imagination). This made me more amenable to claims that some people can have mental experiences that others can’t, and that denying a mental experience claimed by thousands of very trustworthy-seeming people is fraught.

-

I have really low sex drive in certain areas (I sometimes round this off to “asexual”, even though that’s not quite right). This might be because I was on SSRIs for ten years as a kid. Until I was in my mid-20s, I didn’t really realize this. I thought that people talking about teenage boys desperate to see their neighbor naked or something were making humorous exaggerations. Or that I (or my partners) were just unusually bad at sex and eventually I would figure it out (and teenage boys talking about how much they loved sex even though they were sexually inexperienced were just boasting or exaggerating). Eventually I realized that no, I was just missing a very important and very blissful mental experience that a lot of other people had naturally. This has made me more sensitive to believing other people could be having strange mental experiences I’m missing.

-

You might ask: why was I on SSRIs for several years? Answer - I have a weird subtype of OCD where I feel a strong compulsion to perform certain meaningless actions. For example, it might feel self-evident to me that it’s wrong that my left hand hasn’t touched a certain glass, so I reach out and touch it. I’ve since gotten this mostly under control and I feel fine. But a big part of my inner life seems completely insane to other people and I try not to talk about it very much. This has left me with some sympathy for other people whose inner lives might seem insane to spectators.

-

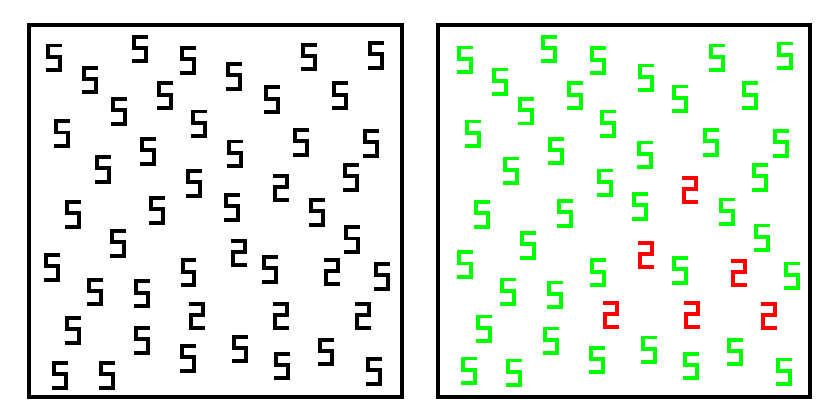

In college I had the great honor of hearing a lecture by legendary neuroscientist V. S. Ramachandran, who helped put synaethesia on the neuroscientific map. Synaesthesia is where people have an association between unlike sensory or conceptual domains - most often color and something else. For example, each number might be a different color. Many people have this to a weak degree (Aella has an interesting survey here) but some people apparently have it to such a strong degree that it almost-literally jumps out of the page. Ramachandran demonstrated this in an experiment by showing that these people could identify 2s among a sea of 5s faster than everyone else: In his paper on the phenomenon, Ramachandran wrote that he got pushback from other scientists for studying this, since they thought synaesthetes: “…are just crazy. The phenomenon is simply the result of a hyperactive imagination. Or maybe they are trying to draw attention to themselves by claiming to be special or different in some way.” You can read the paper here. This has left me nervous about explanations where people only say they have a weird mental ability to “draw attention” or “claim to be different”.

Subjects were shown the image on the left, where it’s hard and time-consuming to find the 2s among the 5s. Extremely synaesthesic subjects, who strongly associate numbers with colors, perceived something more like the image on the right, and so were able to find the 2s faster than everyone else. Source: Wikipedia

Subjects were shown the image on the left, where it’s hard and time-consuming to find the 2s among the 5s. Extremely synaesthesic subjects, who strongly associate numbers with colors, perceived something more like the image on the right, and so were able to find the 2s faster than everyone else. Source: Wikipedia

-

Speaking of Ramachandran, he also did a lot of research on phantom limb pain, ie someone who has had their right arm amputated, but still feels pain in their right arm, or at least the empty space where their right arm should be. This is at least as weird as any of these other examples, but as far as I know everyone acknowledges it exists. I think this is just because most people first heard it from fancy scientists who assured everybody that their patients said it existed. But I would like to believe things even before fancy scientists verify them.

-

A while ago I wrote a post on this topic, What Universal Human Experiences Are You Missing Without Realizing It? - based on the experience of a Quora writer who had anosmia (the inability to smell things) for many years, and had assumed nobody else could really smell things and they were just sort of lying about it or exaggerating or using flowery language or something. You can read through the 913 comments for other stories like this.

There’s a rationalist skill related to Conservation Of Expected Evidence, which is something like “jumping to the end of the story”. If there’s a story about how every time you believe something, you turn out to be wrong, and you keep updating slightly downward, at some point you can just jump to the end of the story where you have a very low prior indeed. This is hard - you don’t want to jump too far - but it’s sometimes served me well. I think this is one of those times.

Resident Contrarian writes:

More to the point: the kind of norm that’s being demanded here requires you to believe almost any claim, provided you can’t immediately falsify it. Or barring that to at least say you do, even if you don’t do the stuff that belief would imply you should.

[…]

I think it’s better to acknowledge a middle position - one where someone is not actively believed, where the listener remains unconvinced, without having the default assumption being that they are by doing this committing an act indistinct from flat-out accusations of dishonestly. In other words: People should be able to express reasonable, honestly-felt doubt without being thought of as expressing hate or disdain.

RC is doing an old trick: summing up his opponent’s position as an extreme absolute, then summing up his own position as “it’s diverse and complicated and a middle ground”.

I reject this characterization. Everything is a middle ground. The whole point of all this Bayes stuff is that “the middle ground” is wide and worth fighting over. We can have a non-absolute middle ground with 1% probability, a non-absolute middle ground with 99% probability, or anything in between. I’m not doing the morality/etiquette thing of demanding a norm that you believe people, I’m doing an epistemic thing of providing justifications for a prior that you believe people.

Contrarian again:

I’d like to accommodate the jhana-claimer and to be politely credulous, but consider this: if I went with believing the jhanists based on the level of evidence they provide, I’d also have to believe both the Spoonies, the DID people, the astral-projecting Wiccans, people who see auras, and John Edwards (pick one; almost any John Edwards works for this sentence).

You should believe the spoonies! You should believe the DID people! You should believe that people experience astral projection - it’s just a cheap off-brand lucid dream, and I’ve personally tried lucid dreaming and can confirm it’s real! You should believe that people experience auras - see eg Paranormal Misinterpretations Of Vision Phenomena, Colored Halos Around Faces And Emotion-Evoked Colors: A New Form Of Synesthesia (note first author!), the many stories of people seeing auras while on drugs, and my own Lots Of People Going Around With Mild Hallucinations All The Time! You should believe that people experience John Edwards - I think my parents voted for him in 2004!

I’m just not really in the business of coming up with convoluted explanations for why everyone who reports weird mental experiences must be lying in order to sound “quirky”, and actually everyone’s brain works similarly to mine. I’m not trying to set up a social norm here, and it’s fine if you disagree with me. I’m just saying I think this is usually a bad gamble.