Critical Periods For Language: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

Scott Young writes about Seven Expert Opinions I Agree With That Most People Don’t. I like most of them, but #6, Children don’t learn languages faster than adults , deserves a closer look.

Some people imagine babies have some magic language ability that lets them pick up their first language easily, even as we adults struggle through verb conjugations to pick up our second. But babies are embedded in a family of first-language speakers with no other options for communication. If an English-speaking adult was placed in a monolingual Spanish family, in a part of Spain with no English speakers, after a few years they might find they’d learned Spanish “easily” too. So Scott says:

Common wisdom says if you’re going to learn a language, learn it early. Children regularly become fluent in their home and classroom language, indistinguishable from native speakers; adults rarely do.

But even if children eventually surpass the attainments of adults in pronunciation and syntax, it’s not true that children learn faster. Studies routinely find that, given the same form of instruction/immersion, older learners tend to become proficient in a language more quickly than children do—adults simply plateau at a non-native level of ability, given continued practice.

I take this as evidence that language learning proceeds through both a fast, explicit channel and a slow, implicit channel. Adults and older children may have a more fully developed fast channel, but perhaps have deficiencies in the slow channel that prevent completely native-like acquisition.

Is this true?

My read is: scientists are still debating the intricacies, something like it is kind of true, but it’s probably not exactly true.

There’s A Critical Period For First Language Learning

This isn’t really what anyone is asking, but it will help clarify some later questions: children need to learn some language before age 5 - 10, or they’ll lose the ability to learn languages at all.

Older research on this topic focused on feral children like Genie, who had been abandoned or abused and so never learned language. They had a hard time learning language even after being reintegrated into society; most never succeeded. But skeptics argued these children had lots of other problems besides lack of language exposure; maybe the abuse and neglect damaged their brains.

The situation was clarified by the discovery of Chelsea, who was born deaf in “a rural community”. Her family tried to get her support, but the process was bungled, nobody in her area knew sign language, and so she was raised without exposure to language (but otherwise normally). At age 32, social services “discovered” her, gave her hearing aids which made her hearing fully functional, and referred her to scientists who tried to teach her language. After ten years, she had a good vocabulary and a good understanding of the practicalities of communication, but was never able to develop anything like a normal grammar.

(interestingly, she was fine at math, suggesting that grammar and numeracy are dissociable)

Studies of other deaf people exposed to sign language or hearing aids at various ages suggest that waiting until age 5 to learn language is worse than starting at birth. I can’t find anything more specific about younger ages.

The Younger You Start Learning A Second Language, The Better

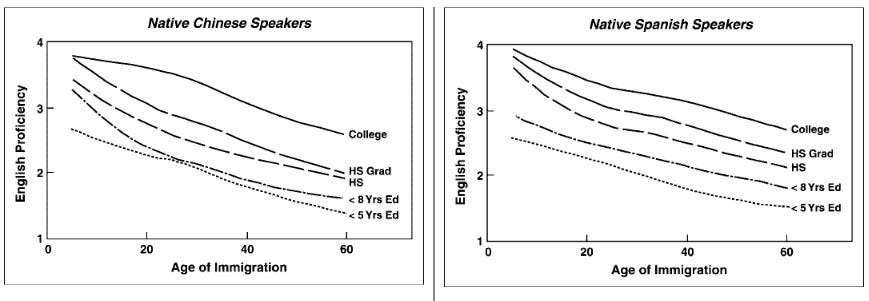

The typical study here looks at census records of tens of thousands of US immigrants and correlates when they immigrated with how good their English is. Here’s a typical finding (source):

English proficiency declines based on age at entering the US.

This isn’t a trivial finding. Previous research found that immigrants’ English proficiency asymptoted out after ten years, and the study authors limited their sample to immigrants who had been in the US longer than that. So we’re asked to believe this isn’t a function of how long each group has been in the US. Suppose everyone here has been in the US thirty years. People who enter the US at 10 (and are now 40) have better English than people who enter at 20 (and are now 50). Why? It seems like they must be able to learn languages better (or at least to a higher final level) when they’re younger.

But this also doesn’t show a “critical window”. There is no single age where people go from “good at English” to “bad at English”. It’s just worse and worse over time.

But would a critical window really produce a discontinuity on the graph? Suppose there was a window from 1 to 10. Someone who immigrated at 9 would get one year within the window (to learn faster and better than normal), and someone who immigrated at 10 would get zero years within the window. So they might not end up looking very different. It would just be a matter of slope, which might be easy to miss.

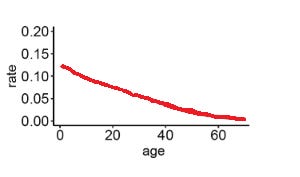

Hartshorne, Tenenbaum, and Pinker do a big-data, fancy-statistics version of this experiment to investigate concerns like these. They got 600,000 bilingual English-speakers from around the world to complete a fun online quiz about their English grammar ability, and found the following:

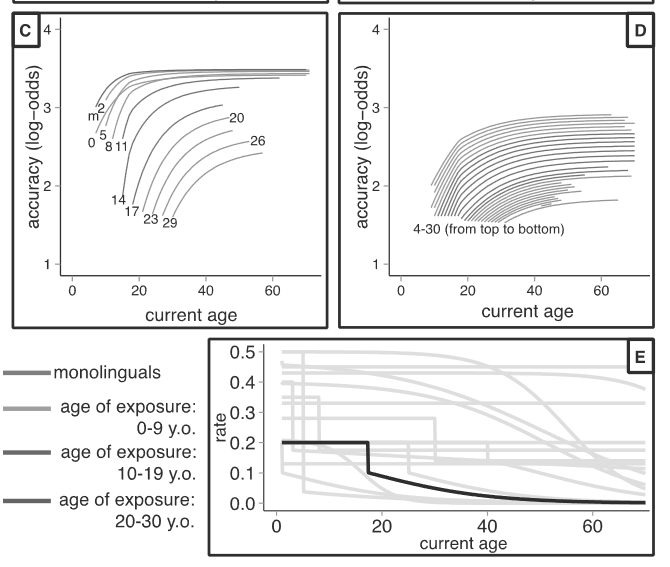

Top left is “monolinguals and immersion learners”, top right is “non-immersion learners”. Unlike the claim in the last study, there’s no sign of any asymptote after ten years, maybe because they asked many more questions and used log accuracy.

Top left is “monolinguals and immersion learners”, top right is “non-immersion learners”. Unlike the claim in the last study, there’s no sign of any asymptote after ten years, maybe because they asked many more questions and used log accuracy.

Language learning ability is high until about age 18, when it crashes. After that it keeps going down, but more gradually. I don’t think they’re claiming this is the exact curve, just that it fit better than a dozen or so alternatives they looked at.

This is a weird result, not really predicted by any theory. The authors wonder if it’s related to people learning languages better while still in school. But this is a high-functioning sample and you would expect many of them to go to college. Also, many of these people are immersion learners, and it’s not obvious why school would be better for immersion learning than whatever comes after (eg the workplace).

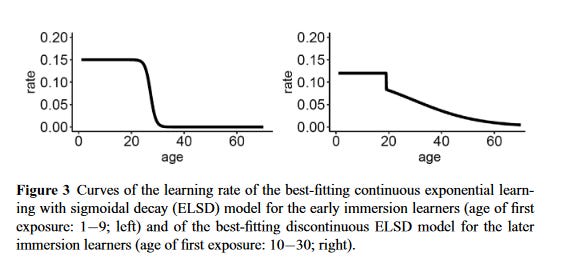

Van der Slik et al are so skeptical that they reanalyze the data with a different strategy for separating language learner strategies. They find that mostly non-immersion learners show the discontinuous pattern above, with monolinguals, bilinguals, and “early immersion learners” showing a more continuous pattern. This makes it clearer that the drop involves leaving school (where non-immersion learners are most likely to get language instruction). Their curves look like this:

Early immersion learners (starting before 10) show a non-school-dependent pattern that saturates around age 25. Late immersion learners show a school-dependent pattern (probably because they don’t start - or at least finish - immersion learning until they’re done with school) that saturates either gradually (if you believe the decline is due to saturation) or not at all (if you believe the decline is due to inherent age effects).

Early immersion learners (starting before 10) show a non-school-dependent pattern that saturates around age 25. Late immersion learners show a school-dependent pattern (probably because they don’t start - or at least finish - immersion learning until they’re done with school) that saturates either gradually (if you believe the decline is due to saturation) or not at all (if you believe the decline is due to inherent age effects).

Taken at face value, monolinguals and early immersion learners (ie those least dependent on school, the pattern on the left) learn language at a constant rate until their mid-twenties, when the rate suddenly (albeit “continuously”) drops. This is also a surprising result; although the authors don’t say so, I wonder if it is best explained by people already knowing the language pretty well by their mid-twenties and so not having much left to learn. I thought the original researchers adjusted for this by using log scores instead of raw scores, but I can’t otherwise explain why learning rate is so much higher in early-immersion 40 years olds compared to late-immersion 40 year olds.

Could we just subtract out the effect of schooling from the late immersion learners to get a true rate?:

Not really, this pattern shows less learning at eg age 20 than is observed by the early immersion learners.

Aside from saying that learning rate seems high in youth, probably stays high for a while, and then seems to go down in some kind of plausibly-continuous way most marked between 20 and 30, I’m pretty stumped here.

All of these models agree that there’s no special mystical reason why someone who starts learning at 30 can’t gain native-level proficiency. It’s just that thirty-year olds have low language learning rates. Let’s say it would take forty years of learning at that rate to gain native-level proficiency. Even if learners were willing to wait until age 70, by the time they were 50 they’d be only halfway, and their language learning rate would have decayed further, and now it would take more than twenty more years. So there’s some age at which reaching native proficiency becomes practically impossible for most people, based on learning rate and the human lifespan.

Is this learning rate decline language-specific, or true of any task? The authors assume the former, but I don’t know why.

These kinds of studies have not completely won the debate; see eg The Critical Period Hypothesis For [Second Language] Acquisition: An Unfalsifiable Embarassment? It doesn’t disagree with HTP exactly, just points out that its results are strange, contradict most prior definitions of “critical periods”, and probably wouldn’t naturally be thought of as a “critical period” if that term wasn’t already in popular use.

Do Young People Learn Their First Language Faster Than Older People Can Learn A Second?

This is closest to the original question.

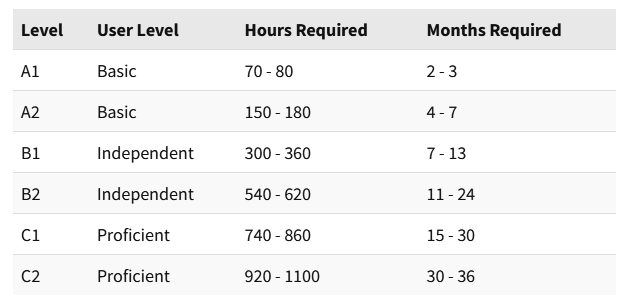

Here’s one language-learning site’s estimate for how long it would take a dedicated English-speaker to learn Spanish:

…where C2 is an impressive level of fluency sufficient for eg difficult intellectual work.

Meanwhile, 36-month-old Spanish children will still be barely saying their first complete sentences. Advantage: adults!

This is obviously unfair since young children are very dumb and have to spend a year just learning to produce sounds at all, but I’m not sure what else it would mean to answer this question.

Is There Something Going On Where Children Learn Better Implicitly, And Adults Learn Better By Explicit Rules?

In a few studies (1, 2), if you try to teach adults and children the same fake language, adults learn faster whether it’s taught implicitly or explicitly. If I understand right, no evidence was found for children having a separate implicit language track adults lack access to.

Are There Subparts Of Language That Definitely Work By Critical Windows?

The strongest argument is for accent/pronunciation. In the standard theory, babies start out equally able to recognize all ~1000 possible phonemes, but soon pare them down to the ones included in their native language, and have trouble getting them back later (eg monolingual Asians who cannot distinguish “R” and “L”).

This doesn’t seem to match experiment, where the “critical period” for having a perfect accent lasts until age 10 - 12.

Also, sometimes talented people who try really hard can have good pronunciation even if they start after that time.

I wonder if this is just the same phenomenon of declining learning rates observed by Pinker et al.

Summary

Children seem to be able to pick up second languages faster than adults. It’s hard to tell exactly when the learning rate slows, or to be sure this is a biological phenomenon instead of an effect of school ending or picking low-hanging fruits. Mastering a language perfectly in adulthood is hard, but maybe just because there’s not enough time to learn it at adult’s slower learning rates.

Babies don’t seem any better than older children (eg 17 year olds), and are limited by being babies. The difference between their excellent ability to learn a first language, and (for example) a middle-schooler struggling to learn a second language, probably is just exposure and motivation, and not an additional magic language ability.