Deceptively Aligned Mesa-Optimizers: It's Not Funny If I Have To Explain It

I.

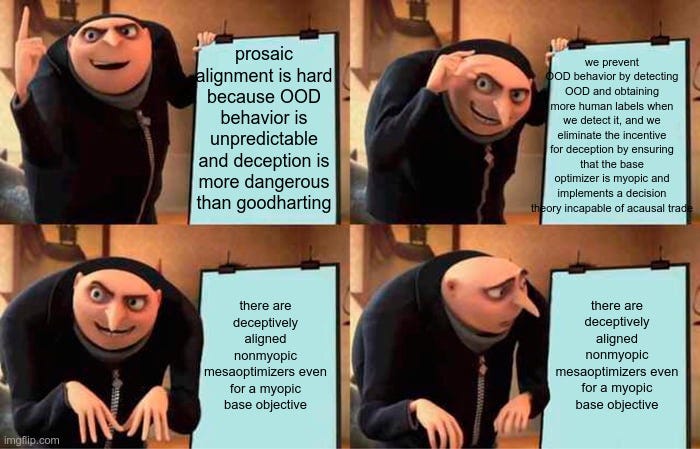

Our goal here is to popularize obscure and hard-to-understand areas of AI alignment, and surely this meme (retweeted by Eliezer last week) qualifies:

Leo Gao @nabla_theta

Leo Gao @nabla_theta [4:24 AM ∙ Dec 13, 2021

[4:24 AM ∙ Dec 13, 2021

42Likes2Retweets](https://twitter.com/nabla_theta/status/1470248132533391363)

So let’s try to understand the incomprehensible meme! Our main source will be Hubinger et al 2019, Risks From Learned Optimization In Advanced Machine Learning Systems.

Mesa- is a Greek prefix which means the opposite of meta-. To “go meta” is to go one level up; to “go mesa” is to go one level down (nobody has ever actually used this expression, sorry). So a mesa-optimizer is an optimizer one level down from you.

Consider evolution, optimizing the fitness of animals. For a long time, it did so very mechanically, inserting behaviors like “use this cell to detect light, then grow toward the light” or “if something has a red dot on its back, it might be a female of your species, you should mate with it”. As animals became more complicated, they started to do some of the work themselves. Evolution gave them drives, like hunger and lust, and the animals figured out ways to achieve those drives in their current situation. Evolution didn’t mechanically instill the behavior of opening my fridge and eating a Swiss Cheese slice. It instilled the hunger drive, and I figured out that the best way to satisfy it was to open my fridge and eat cheese.

So I am a mesa-optimizer relative to evolution. Evolution, in the process of optimizing my fitness, created a second optimizer - my brain - which is optimizing for things like food and sex. If, like Jacob Falkovich, I satisfy my sex drive by creating a spreadsheet with all the women I want to date, and making it add up all their good qualities and calculate who I should flirt with, then - on the off-chance that spreadsheet achieved sentience - it would be a mesa-optimizer relative to me, and a mesa-mesa-optimizer relative to evolution. All of us - evolution, me, the spreadsheet - want broadly the same goal (for me to succeed at dating and pass on my genes). But evolution delegated some aspects of the problem to my brain, and my brain delegated some aspects of the problem to the spreadsheet, and now whether I mate or not depends on whether I entered a formula right in cell A29.

(by all accounts Jacob and Terese are very happy)

Returning to machine learning: the current process of training AIs, gradient descent, is a little bit like evolution. You start with a semi-random AI, throw training data at it, and select for the weights that succeed on the training data. Eventually, you get an AI with something resembling intuition. A classic dog-cat classifier can look at an image, process a bunch of features, and return either “dog” or “cat”. This AI is not an optimizer. It’s not planning. It has no drives. It’s not thinking “If only I could figure out whether this was a dog or a cat! I wonder what would work for this? Maybe I’ll send an email to the American Kennel Club, they seem like the sort of people who would know. That plan has a higher success rate than any of my other plans.” It’s just executing learned behaviors, like an insect. “That thing has a red dot on it, must be a female of my species, I should mate with it”. Good job, now you’re mating with the Japanese flag.

But just as evolution eventually moved beyond mechanical insects and created mesa-optimizers like humans, so gradient descent could, in theory, move beyond mechanical AIs like cat-dog classifiers and create some kind of mesa-optimizer AI. If that happened, we wouldn’t know; right now most AIs are black boxes to their programmers. We would just notice that a certain program seemed faster or more adaptable than usual (or didn’t - there’s no law saying optimizers have to work better than instinct-executors, they’re just a different mind-design).

Mesa-optimizers would have an objective which is closely correlated with their base optimizer, but it might not be perfectly correlated. The classic example, again, is evolution. Evolution “wants” us to reproduce and pass on our genes. But my sex drive is just that: a sex drive. In the ancestral environment, where there was no porn or contraceptives, sex was a reliable proxy for reproduction; there was no reason for evolution to make me mesa-optimize for anything other than “have sex”. Now in the modern world, evolution’s proxy seems myopic - sex is a poor proxy for reproduction. I know this and I am pretty smart and that doesn’t matter. That is, just because I’m smart enough to know that evolution gave me a sex drive so I would reproduce - and not so I would have protected sex with somebody on the Pill - doesn’t mean I immediately change to wanting to reproduce instead. Evolution got one chance to set my value function when it created me, and if it screwed up that one chance, it’s screwed. I’m out of its control, doing my own thing.

(I feel compelled to admit that I do want to have kids. How awkward is that for this argument? I think not very - I don’t want to, eg, donate to hundreds of sperm banks to ensure that my genes are as heavily-represented in the next generation as possible. I just want kids because I like kids and feel some vague moral obligations around them. These might be different proxy objective evolution gave me, maybe a little more robust, but not fundamentally different from the sex one)

In fact, we should expect that mesa-optimizers usually have proxy objectives different from the base optimizers’ objective. The base optimizer is usually something stupid that doesn’t “know” in any meaningful sense that it has an objective - eg evolution, or gradient descent. The first thing it hits upon which does a halfway decent job of optimizing its target will serve as a mesa-optimizer objective. There’s no good reason this should be the real objective. In the human case, it was “a feeling of friction on the genitals”, which is exactly the kind of thing reptiles and chimps and australopithecines can understand. Evolution couldn’t have lucked into giving its mesa-optimizers the real objective (“increase the relative frequency of your alleles in the next generation”) because a reptile or even an australopithecine is millennia away from understanding what an “allele” is.

II.

Okay! Finally ready to explain the meme! Let’s go!

Prosaic alignment is hard…

“Prosaic alignment” (see this article for more) means alignment of normal AIs like the ones we use today. For a while, people thought those AIs couldn’t reach dangerous levels, and that AIs that reached dangerous levels would have so many exotic new discoveries that we couldn’t even begin to speculate on what they would be like or how to align them.

After GPT-2, DALL-E, and the rest, alignment researchers got more concerned that AIs kind of like current models could be dangerous. Prosaic alignment - trying to align AIs like the ones we have now - has become the dominant (though not unchallenged) paradigm in alignment research.

“Prosaic” doesn’t necessarily mean the AI cannot write poetry; see Gwern’s AI generated poetry for examples.

…because OOD behavior is unpredictable

“OOD” stands for “out of distribution”. All AIs are trained in a certain environment. Then they get deployed in some other environment. If it’s like the training environment, presumably their training is pretty relevant and helpful. If it’s not like the training environment, anything can happen. Returning to our stock example, the “training environment” where evolution designed humans didn’t involve contraceptives. In that environment, the base optimizer’s goal (pass on genes) and the mesa-optimizer’s goal (get genital friction) were very well-aligned - doing one often led to the other - so there wasn’t much pressure on evolution to look for a better proxy. Then 1957, boom, the FDA approves the oral contraceptive pill, and suddenly the deployment environment looks really really different from the training environment and the proxy collapses so humiliatingly that people start doing crazy things like electing Viktor Orban prime minister.

So: suppose we train a robot to pick strawberries. We let it flail around in a strawberry patch, and reinforce it whenever strawberries end up in a bucket. Eventually it learns to pick strawberries very well indeed.

But maybe all the training was done on a sunny day. And maybe what it actually learned was to identify the metal bucket by the way it gleamed in the sunlight. Later we ask it to pick strawberries in the evening, where a local streetlight is the brightest thing around, and it throws the strawberries at the streetlight instead.

So fine. We train it in a variety of different lighting conditions, until we’re sure that, no matter what the lighting situation, the strawberries go in the bucket. Then one day someone with a big bulbous red nose wanders on to the field, and the robot tears his nose off and pulls it into the bucket. If only there had been someone with a nose that big and red in the training distribution, so we could have told it not to do that!

The point is, just because it’s learned “strawberries into bucket” in one environment, doesn’t mean it’s safe or effective in another. And we can never be sure we’ve caught all the ways the environment can vary.

…and deception is more dangerous than Goodharting.

To “Goodhart” is to take advantage of Goodhart’s Law: to follow the letter of your reward function, rather than the spirit. The ordinary-life equivalent is “teaching to the test”. The system’s programmers (eg the Department of Education) have an objective (children should learn). They delegate that objective to mesa-optimizers (the teachers) via a proxy objective (children should do well on the standardized test) and a correlated reward function (teachers get paid more if their students get higher test scores). The teachers can either pursue the base objective for less reward (teach children useful skills), or pursue their mesa-level objective for more reward (teach them how to do well on the test). An alignment failure!

This sucks, but it’s a bounded problem. We already know that some teachers teach to the test, and the Department of Education has accepted this as a reasonable cost of having the incentive system at all.

We might imagine our strawberry-picker cutting strawberries into little pieces, so that it counts as having picked more strawberries. Again, it sucks, but once a programmer notices it can be fixed pretty quickly (as long as the AI is still weak and under control).

What about deception? Suppose the strawberry-picker happens to land on some goal function other than the intended one. Maybe, as before, it wants to toss strawberries at light sources, in a way that works when the nearest light source is a metal bucket, but fails when it’s a streetlight. Our programmers are (somewhat) smart and careful, so during training, they test it at night, next to a streetlight. What happens?

If it’s just a dumb collection of reflexes trained by gradient descent, it throws the strawberry at the streetlight and this is easily caught and fixed.

If it’s a very smart mesa-optimizer, it might think “If I throw the strawberry at the streetlight, I will be caught and trained to have different goals. This totally fails to achieve my goal of having strawberries near light sources. So throwing the strawberry at the light source this time, in the training environment, fails to achieve my overall goal of having strawberries thrown at light sources in general. I’ll do what the humans want - put the strawberry in the bucket - for now.” So it puts the strawberry in the bucket and doesn’t get caught. Then, as soon as the humans stop looking, it throws strawberries at the streetlight again.

Deception is more dangerous than Goodharting because Goodharting will get caught and trained away, and deception might not.

I might not be explaining this well, see also Deceptively Aligned Mesa-Optimizers? It’s More Likely Than You Think:

We prevent OOD behavior by detecting OOD and obtaining more human labels when we detect it…

If you’re (somewhat) careful, you can run your strawberry-picking AI at night, see it throw strawberries at streetlights, and train it out of this behavior (ie have a human programmer label it “bad” so the AI gradient-descends away from it)

…and we eliminate the incentive for deception by ensuring that the base optimizer is myopic

A myopic optimizer is one that reinforces programs based only on their performance within a short time horizon. So for example, the outside gradient descent loop might grade a strawberry picker only on how well it did picking strawberries for the first hour it was deployed.

If this worked perfectly, it would create an optimizer with a short time horizon. When it considered deceiving its programmers in order to get a payoff a few days later when they stopped watching it, it wouldn’t bother, since a few days later is outside the time horizon.

…and implements a decision theory incapable of acausal trade.

You don’t want to know about this one, really. Just pretend it never mentioned this, sorry for the inconvenience.

There are deceptively-aligned non-myopic mesa-optimizers even for a myopic base objective.

Even if the base optimizer is myopic, the mesa-optimizer might not be.

Evolution designed humans myopically, in the sense that we live some number of years, and nothing that happens after that can reward or punish us further. But we still “build for posterity” anyway, presumably as a spandrel of having working planning software at all. Infinite optimization power might be able to evolve this out of us, but infinite optimization power could do lots of stuff, and real evolution remains stubbornly finite.

Maybe it would be helpful if we could make the mesa-optimizer itself myopic (though this would severely limit its utility). But so far there is no way to make a mesa-optimizer anything. You just run the gradient descent and cross your fingers.

The most likely outcome: you run myopic gradient descent to create a strawberry picker. It creates a mesa-optimizer with some kind of proxy goal which corresponds very well to strawberry picking in the training optimization, like flinging red things at lights (realistically it will be weirder and more exotic than this). The mesa-optimizer is not incentivized to think about anything more than an hour out, but does so anyway, for the same reason I’m not incentivized to speculate about the far future but I’m doing so anyway. While speculating about the far future, it realizes that failing to pick strawberries correctly now will thwart its goal of throwing red things at light sources later. It picks strawberries correctly in the training distribution, and then, when training is over and nobody is watching, throws strawberries at streetlights.

(Then it realizes it could throw lots more red things at light sources if it was more powerful, achieves superintelligence somehow, and converts the mass of the Earth into red things it can throw at the sun. The end.)

III.

You’re still here? But we already finished explaining the meme!

Okay, fine. Is any of this relevant to the real world?

As far as we know, there are no existing full mesa-optimizers. AlphaGo is kind of a mesa-optimizer. You could approximate it as a gradient descent loop creating a good-Go-move optimizer. But this would only be an approximation: DeepMind hard-coded some parts of AlphaGo, then gradient-descended other parts. Its objective function is “win games of Go”, which is hard-coded and pretty clear. Whether or not you choose to call it a mesa-optimizer, it’s not a very scary one.

Will we get scary mesa-optimizers in the future? This ties into one of the longest-running debates in AI alignment - see eg my review of Reframing Superintelligence , or the Eliezer Yudkowsky/Richard Ngo dialogue. Optimists say: “Since a goal-seeking AI might kill everyone, I would simply not create one”. They speculate about mechanical/instinctual superintelligences that would be comparatively easy to align, and might help us figure out how to deal with their scarier cousins.

But the mesa-optimizer literature argues: we have limited to no control over what kind of AIs we get. We can hope and pray for mechanical instinctual AIs all we want. We can avoid specifically designing goal-seeking AIs. But really, all we’re doing here is setting up a gradient descent loop and pressing ‘go’. Then the loop evolves whatever kind of AI best minimizes our loss function.

Will that be a mesa-optimizer? Well, I benefit from considering my actions and then choosing the one that best achieves my goal. Do you benefit from this? It sure does seem like this helps in a broad class of situations. So it would be surprising if planning agents weren’t an effective AI design. And if they are, we should expect gradient descent to stumble across them eventually.

This is the scenario that a lot of AI alignment research focuses on. When we create the first true planning agent - on purpose or by accident - the process will probably start with us running a gradient descent loop with some objective function. That will produce a mesa-optimizer with some other, potentially different, objective function. Making sure you actually like the objective function that you gave the original gradient descent loop on purpose is called outer alignment. Carrying that objective function over to the mesa-optimizer you actually get is called inner alignment.

Outer alignment problems tend to sound like Sorcerer’s Apprentice. We tell the AI to pick strawberries, but we forgot to include caveats and stop signals. The AI becomes superintelligent and converts the whole world into strawberries so it can pick as many as possible. Inner alignment problems tend to sound like the AI tiling the universe with some crazy thing which, to humans, might not look like picking strawberries at all, even though in the AI’s exotic ontology it served as some useful proxy for strawberries in the training distribution. My stand-in for this is “converts the whole world into red things and throws them into the sun”, but whatever the AI that kills us really does will probably be weirder than that. They’re not ironic Sorcerer’s Apprentice-style comeuppance. They’re just “ what?” If you wrote a book about a wizard who created a strawberry-picking golem, and it converted the entire earth into ferrous microspheres and hurled them into the sun, it wouldn’t become iconic the way Sorcerer’s Apprentice did.

Inner alignment problems happen “first”, so we won’t even make it to the good-story outer alignment kind unless we solve a lot of issues we don’t currently know how to solve.

For more information, you can read:

-

The original Hubinger paper, which speculates about what factors make AIs more or less likely to spin off mesa-optimizers

-

Rafael Harth’s Inner Alignment: Explain Like I’m 12 Edition,

-

The 60-odd posts on the Alignment Forum tagged “inner alignment”

-

As always, Richard Ngo’s AI safety curriculum