Does Georgism Work? Part 2: Can Landlords Pass Land Value Tax on to Tenants?

[Lars Doucet won this year’sBook Review Contest with his review of Henry George’s Progress and Poverty. Since then, he’s been researching Georgism in more depth, and wants to follow up with what he’s learned. I’ll be posting three of his Georgism essays here this week, and you can read his other work at Fortress Of Doors]

Hi, my name’s Lars Doucet (not Scott Alexander), and this is a guest post in an ongoing series that assesses the empirical basis for the economic philosophy of Georgism.

Part 0 - Book Review: Progress & Poverty

Part I - Is Land Really a Big Deal?

Part II - Can Land Value Tax be passed on to Tenants? 👈(You are here)

Part III - Can Unimproved Land Value be Accurately Assessed Separately from Buildings?

There were a lot of great comments to Part I. Most zeroed in on the practical aspects of implementing Georgism, such as how to deal with what Gordon Tullock calls The Transitional Gains Trap. Others brought up various perceived political obstacles and a few other topics (yes, I know about zoning, which is also a big deal). With a few exceptions, I didn’t see much pushback on the core thesis of Part I, that land is a really big deal. In fact, many of the strongest opponents of LVT seem opposed precisely because they agree that land is a big deal.

I can’t respond to everything people have said without spending another few months researching, but rest assured I will briefly address the most common points at the end of Part III. Anything that remains unanswered after that will have to wait for future articles.

Georgists assert that landlords cannot pass Land Value Tax (LVT) on to their tenants. (Land Value Tax is a tax on the unimproved value of land alone, excluding all the buildings and other improvements.) Many critics are skeptical of this, because just about every other tax in the world is passed on. Why should LVT be so special?

By George, if Land Value Tax is easily passed on to tenants, then it has no power to curb land speculation, and you can stop reading this article.

First, let’s explain the theoretical model for why this isn’t supposed to be possible, and then let’s see if it actually works that way in the real world.

1. Theory

Imagine I’m a landlord, and I have a vacant lot I’m renting to a tenant who’s got a mobile home parked there. What’s going to happen if a Land Value Tax is imposed on me? Well, I’m already charging as much as the market will bear. If I charge any more, my tenant will move out. But why shouldn’t I be able to pass on the tax to the tenant? If you tax gasoline or cigarettes, the prices go up and are ultimately borne by the customer. Why should land be any different?

The difference is that the supply of gasoline and cigarettes fluctuates, because you can produce more or less of them. When you put a tax on gasoline or cigarettes of even a few cents, somewhere in the economy there is a marginal oil well or a marginal tobacco farm whose profit margin was the same as or less than the tax. Now their profit is entirely wiped out, so what’s the point of producing any more? Price signals from the market are telling them to stop producing and do something else. And price is ultimately driven by supply and demand, not the wishes of a seller. Even a dedicated cartel like OPEC can’t enforce high oil prices by fiat. They do it by cutting off production and driving down the global supply of oil until people are forced to pay the price OPEC wants.

Okay, let’s go back to land. How does Land Value Tax drive down land prices? The important thing to keep in mind is that land value (purchase price) is a stock, but land income (rent) is a flow. The amount of water flowing out of my tap is a flow; the amount of water currently sitting in my bathtub is a stock. The key thing is that land income drives land price and not the other way around. If a property is capable of generating $10,000/year in rents, then the amount I’m willing to pay to buy it is $10,000 times X, where X represents how many years I’m willing to wait to break even on my investment.

So how does an LVT affect the price of land? Using the bathtub metaphor again, let’s put a valve under the tap, so half of the water goes into the tub and half goes somewhere else. The amount of water flowing out of the tap does not change (the land is as productive as it ever was). However, the amount of water collected in my bathtub does change; five minutes of flow will produce less water in the tub than it did before. If I’m trying to sell my land to someone, they’re going to notice the tax and correctly calculate that it will earn them half as much income over X years, so they’ll pay half as much for it.

And what about rental price? The rental price comes directly from the flow. The land is in demand because of its inherent productivity; someone who occupies that land can generate a certain amount of wealth each month. Without a Land Value Tax, the owner of that land can charge rent up to the difference between their land’s productivity and the best freely available alternative, establishing the “margin of productivity.” This means that as productivity rises, so does the rent. This phenomenon is known as Ricardo’s Law of Rent.

With a Land Value Tax, the owner has to pay that tax every month whether they have a tenant or not. They’re already charging the highest amount the market will bear, and as we’ve already shown, they are unable to change the supply of land. All the leverage is on the side of the tenants, which forces the landlord to eat the tax. The price to buy the land goes down, the price for a tenant to rent it goes down, but the total amount of income the land itself produces (“land rent”) stays the same. A portion of it is just being collected by the taxing agency.

That’s the theory at least. Does it hold up in real life?

According to the evidence, the answer is yes.

2. Empirics

Let’s try to envision what it would take to test this. Imagine a hypothetical country with a decent property assessment scheme already in place. Land and improvements are assessed separately to an objective and equalized standard, and each is taxed at a separate rate. Let’s further say this country’s assessments are widely considered to be fair and well-tested against market values. As a starting condition, each of the counties in this country has its own independent land tax rate. Then, for our experimental intervention, we’ll have all of the counties raise or lower the tax rate on land values randomly within a predefined range, all at the same time. Then we’ll observe what happens to land prices.

Unfortunately for us, countries with the necessary prerequisite assessment policy are few and far between, and sovereign states don’t typically run randomly controlled economic experiments on their population, so I’m afraid–wait, something almost exactly like this happened in Denmark in 2007.

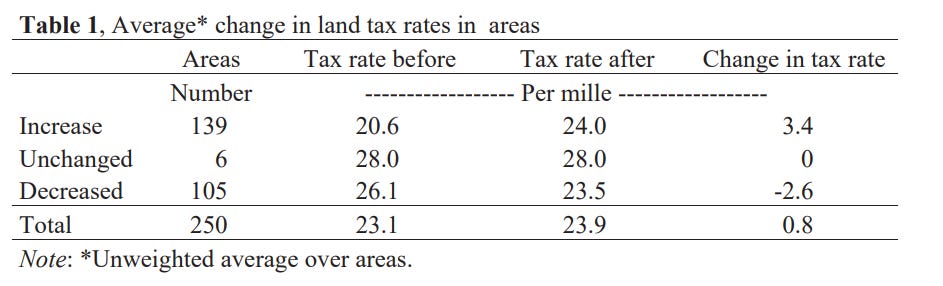

What happened in Denmark was an accident, but you’d be hard pressed to design a better experimental setup if you tried. A 2017 working paper by Høj, Jørgensen, and Schou, entitled “Land Taxes and Housing Prices,” published at the Danish Secretariat of Economic Councils, has the full story.

One day, Denmark decided to redraw all its municipal boundaries. Regions that had been under one local government woke up the next day under a different one, immediately adopting a new set of local regulations and rules, including changed tax rates. This caused a large-scale, semi-random shuffling of Land Value Tax rates overnight.

Crucially, tax assessment policy was pretty much uniform throughout the country. The only thing this shakeup changed with regard to land policy was the actual individual rates of tax on land, set by the local governments. This gives us a nice big N of 250 individual areas, each with a clear before and after change in land tax rate. All of these changes came into being at exactly the same time from a single swift outside intervention, and the overall change in aggregate tax rate was close to zero:

Note the “per mille” – 20.6 per mille = 2.6 per cent, etc.

Note the “per mille” – 20.6 per mille = 2.6 per cent, etc.

The most important thing to note is that this paper claims to get around the “endogeneity problem.” For those of you who aren’t researchers, an endogenous factor is something that originates from inside of the system you’re studying, whereas an exogenous factor is something that originates from outside of it. The “endogeneity problem” is a particularly annoying gremlin that makes it hard to study economics empirically. You can never be sure that the effects you’re measuring were actually caused by the intervention you’re studying. Everything’s a big bowl of soup, and it’s hard to untangle what causes what.

Here’s an example. Let’s say I’m the sovereign Emperor of planet Lars. Among my many powers and privileges is the sole right to set the prime interest rate for the entire Lartian economy. One fine Tuesday, I stroll into my throne room and pull the gilded lever that changes the rate from 1.5% to 1.2%. PhD students rejoice–what a great natural experiment for measuring the effects of changes to the prime interest rate!

Well, except for the pesky fact that sovereign Emperors of planets named after themselves don’t tend to just pull the prime interest rate lever for no reason. Maybe I pulled it because the economy was slowing down or to distract everyone from the unpopular war against the Earthlings I’m currently losing. Were those effects the PhD students observed after I pulled the lever actually caused by me lowering the prime interest rate? Or were they caused by the very forces that drove me to pull the lever in the first place?

What researchers really like to see is an exogenous effect, something that unambiguously comes from outside the system. Going back to planet Lars, one day a ghostly hyperspace beast shows up, instantly eats every car on the entire planet that has a manual transmission, then vanishes in a puff of purple smoke. There’s no way this had anything to do with mysterious epicycles within the Lartian economy. It was a pure exogenous shock, and we can be confident that any subsequent observed changes in the economy had something to do with the beast’s insatiable appetite for stick shifts, especially if the beast was kind enough to leave a few randomly selected areas untouched as a control group. Høj, Jørgensen, and Schou claim the Danish study is the first study of Land Value Tax to enjoy such a clear exogenous trigger:

The method used in the present study is inspired by Borge & Rattsø (2014) who study capitalization of Norwegian property taxes during 1995-97. They also find evidence of complete capitalization. As the authors note themselves, however, examining the relationship between tax rate and house price changes may generally result in endogeneity problems, which they try to avoid using various instrumental variables. The present study is immune to this problem because the Danish local-government reform of 2007 exogenously imposes the tax rate changes.

Backing up the exogenous claim is that, although the change came from the Danish government, it had nothing to do with tax policy. They were just reorganizing the municipal map, and the changes in tax rates were simply the result of whatever jurisdiction your area found itself belonging to the next day. As a quick example, if an area raised land taxes because they needed more money, the fact that the area needed more money could be just as plausible a cause for any observed changes as the change to the land tax rate. But if you change everyone’s land taxes overnight in semi-random directions with no particular regard for the local economic or political situation, you can be more confident that subsequent changes you observe do in fact stem from that intervention.

The authors measure the before-and-after changes, apply a bunch of econometric tests, run it with and without controls just to be sure, and conclude that a Land Value Tax is “fully capitalized” into the price of the property itself. “Fully capitalized” is a fancy way of saying that the price of land goes down proportionately to how much land income is taxed away.

The results demonstrate a clear effect on sales prices of the observed changes in land tax rates. Furthermore, the magnitude of the changes implies full capitalization of the present value of the change in future tax payments for a discount rate of 2.3 per cent, which is within the range of reasonable discount rates for households during the period in question. The analysis consequently supports the hypothesis that perceived permanent land tax changes should be capitalized fully into the price of land and property.

This just means that if you tax land, absent any other interventions, the price of land goes down. The rental income of the land available to the landlord goes down too, which means the landlord is eating the tax and can’t pass it on to the tenant. If the landlord could successfully pass on the tax, we wouldn’t see a decrease in the price of land that amounts to “full capitalization.”

Now, beware the man of one study. Høj, Jørgensen, and Schou cite five other prior studies that support their findings: Oates (1969), Borge & Rattsø (2014), Capozza, Green and Hendershot (1996), Palmon and Smith (1998), and Hilber (2015).

All of these studies support the same conclusion but are not as well controlled and have to do various fancy tests to deal with endogeneity. The Danish study seems like a capstone that replicates the findings of a string of prior studies and puts to rest lingering doubts about endogeneity. If we take the authors’ literature review at face value, it would be a robust finding for the full capitalization hypothesis.

But let’s be thorough. It’s possible these supporting studies are misrepresented, so I looked them up and checked, just in case. They all find strong capitalization of land and property taxes into property values, and all discussed the endogeneity problem and their attempts to account for it. The studies are represented faithfully by the Danish paper and support the same conclusions. Furthermore, four of them are empirical rather than theoretical. These findings are not just the result of models and formulas, but actual real-world observations.

That still leaves the possibility that the Danish authors cherry-picked their supporting studies and ignored everyone who found the opposite conclusions, so I tried to see what a general search for research papers on this subject would turn up and if any papers would not support full capitalization of Land Value Taxes into property prices. Searching Google Scholar for property tax and Land Value Tax capitalization effects, I found nine additional papers.

Supporting:

Bourassa (1987) studies a Land Value Tax system in Pittsburgh and finds that “the incentive effect is significant but the liquidity effect is not. The incentive effect is found to encourage increases in the number of new units constructed in Pittsburgh rather than increases in the average cost of new units”

Skaburskis (1995) concludes, “Tilting tax rates to favor improvements at the expense of land increase the intensity of land development when all other factors are held constant. The policy can increase land values when it is applied to a small portion of a housing market and can reduce land values when applied across the entire housing market.”

Roakes (1996) says, “The evidence verifies that tax capitalization appears to be occurring, but does not clearly determine the resulting price outcome. Land prices increased with a decrease in real property taxes. They also appeared to increase as a result of the tax abatement system. Land prices were determined to decrease as a result of higher land taxes.”

Buettner (2003) finds, “land taxes do capitalize into land values, whereas the monthly rent level remains unaffected by the land tax. In addition, the results point to significant spillovers from amenities and the provision of public goods across municipalities.”

Plummer (2010) finds, “If a LVT causes a property’s future tax payments to increase, then the property’s market value will decrease… On the other hand, if a LVT causes a property’s taxes to decrease, the property’s market value will increase” and notes that the capitalization effects depend on the frequency of reassessments (more frequent assessments = higher capitalization).

Choi (2015) finds, “that a revenue-neutral switch from a capital value property tax to a LVT, or a split-rate tax, results in a reduction in land rent and the tax exclusive price of housing. We find that the land rent gradient becomes flatter while the population density and housing capital gradients become steeper”

Mills (1981) is an interesting study, titled The Non-Neutrality of Land Value Taxation, and frames itself in opposition to LVT. It’s a theoretical paper rather than an empirical one and makes a curious claim: “It is true that a (less than 100 percent) tax on land income is neutral, but this does not extend necessarily to a tax on capitalized land value, or changes therein. The reason is that the discounted sum of payments with the latter tax is not invariant to the intertemporal characteristics of the income stream produced by land. Among options with equal present value, it is greater for income streams skewed to the distant future than for those skewed to the near future.” Mills seems to be arguing that if a piece of land is subject to LVT, people will be willing to pay less to buy it, since it generates less rental income. This sounds like a full capitalization argument to me, which Mills apparently thinks is a bad thing. Regardless of how he feels about it, though, he’s arguing that it happens , ironically putting this paper in the “support” column.

Mixed:

King (1977) doesn’t have a knock-down argument for or against the full capitalization hypothesis, except to point out some quibbles with the analysis methods used in prior studies (including Oates, the seminal paper). King concludes, “our knowledge of the extent of tax capitalization is very much less than is commonly supposed.” One would hope King would have been more impressed by all of the studies that have come out since.

Opposed:

I found one study that clearly and confidently rejects the hypothesis that LVT is fully capitalized into land values.

Wyatt (1994) asserts: “It is found that LVT would increase, not lower land prices and would provide only a small incentive to building construction.” Wyatt relies on his own arguments paired with a literature review, which he asserts finds “no evidence” for the claims of LVT proponents. This is strange, because Oates (1969) contradicts this and is included in Wyatt’s bibliography, though I can’t find a citation of Oates in the text itself. I also found Mills (1981) in his bibliography but not in the text as a citation. He does cite Bourassa (1987), which he interprets as inconclusive. He cites none of the other studies mentioned above, given they hadn’t been published yet. Wyatt offers no new empirical evidence of his own, but he does cite a bunch of other papers I hadn’t seen before. The majority are from the 70’s and 80’s, with only two as recent as the 90’s, the latest one from 1991.

Since Wyatt was the only emphatically critical paper I could find, it’s worth unpacking the citations that back up his arguments to see if they check out. In his introduction, he says:

The Valuer General of New Zealand said, “There was no evidence that the tax would (1) control urban sprawl and speculation in land; (2) encourage the construction of ‘better’ buildings; (3) encourage growth; or (4) cause slums to disappear”

The source he cites is Donald Hagman’s 1965 book The Single Tax and Land Use Planning: Henry George Updated , which I can find cited in a bunch of places but can’t actually seem to locate. The closest I can get is this 1978 article, also by Hagman, posted to Cooperative-Individualism.org, an old school Georgist site. There, Hagman says that when the income tax was first introduced in New Zealand in the 1890’s, Land Value Tax was responsible for 75.7% of the combined tax yield of land + income taxes, but over the course of the next century that figure dropped all the way to 0.5% in 1965 and 0.3% in 1970 (note the placement of the decimal point).

Hagman isn’t clear on why this is. Did land become less important, were assessments depressed, did the land tax rate just go down? What he does say is that various exemptions were put into effect and that New Zealand made some moves away from market-based valuations. So did LVT simply not work as of 1978, or was this particular implementation hobbled?

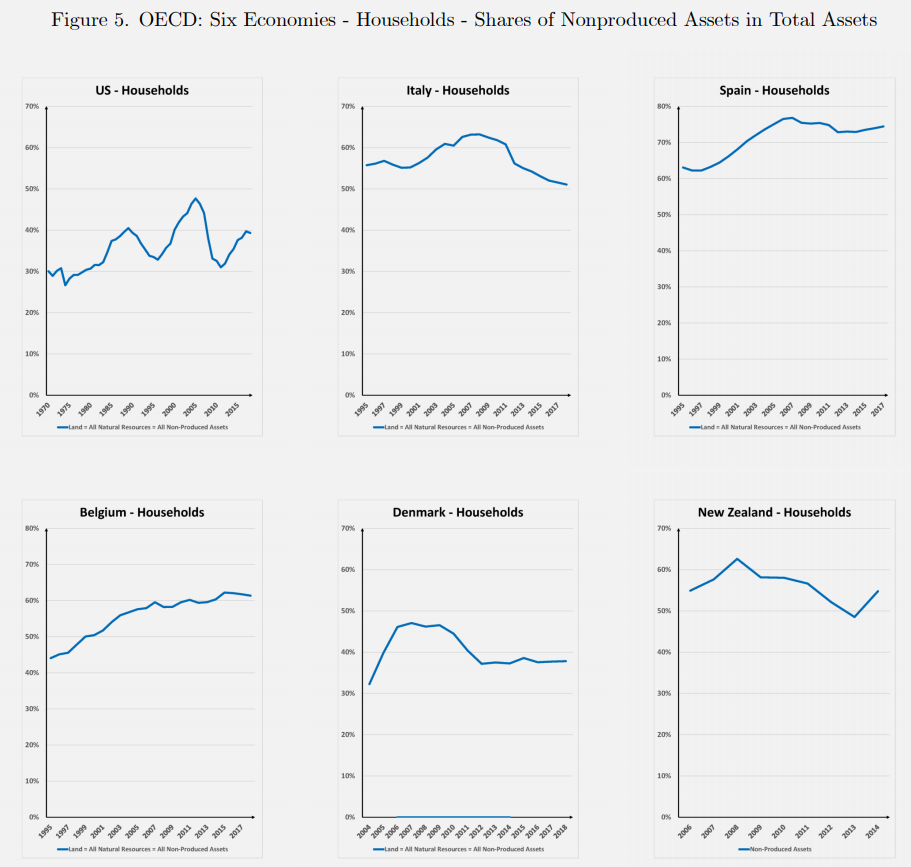

We’ve already shown in Part I that it can’t be that land’s importance in the economy has declined since the 19th century. Concerning New Zealand specifically, Tideman, et al. says that today over half the share of non-produced assets for households is due to land.

And it’s worth reiterating that New Zealand banks put most of their loans towards real estate.

Source: Interest.co.nz

Source: Interest.co.nz

In his case study of Australia for the same article, Hagman points to too low a __ rate of land tax as making it hard to see the full predicted effects borne out. Maybe a similar thing was going on in New Zealand?

it is difficult to determine whether the tax has any significant effect on land development. The tax is not high enough to have the demonstrable effects proponents of land-value taxes suggest will occur.

In any case, I can’t find the specific book Wyatt is citing, and the next best source on the subject from Hagman never tell us exactly why LVT fizzled in New Zealand. What I’m not finding in Hagman is anything like reliable evidence that LVT is not fully capitalized into land prices.

Wyatt cites another source (Pillai 1987) that claims that LVT hasn’t worked in developing countries, but notes that the “LVT” imposed there was a flat tax based on land acreage rather than actual land market value.

Wyatt then follows up with his first solid critique–inaccurate assessments. I’ve just criticized plenty of official assessments in Part I, and Wyatt is absolutely correct that inaccurate assessments are a primary obstacle to successfully implementing LVT. Wyatt says:

It is noteworthy that Pennsylvania, the only state in which many cities have adopted LVT, ranks 49th out of 50 in assessment accuracy.

That’s according to a 1983 article originally published in Fortune Magazine. I don’t know how Pennsylvania fares today, given it’s been 38 years.

I have a whole article dedicated to assessment accuracy coming up next in Part III, so let’s leave that issue aside for now. What is Wyatt’s argument against the full capitalization argument? Does he have any empirical data to back it up?

Grosskopf and Johnson also show that a revenue-neutral shift from the current property tax to a tax only on land value results in higher land prices rather than lower ones (This follows from their derivation that a uniform land and building tax decreases land prices in the long run more than a uniform land tax of equal yield).

Okay, let’s see Grosskopf and Johnson (1982):

The dynamic analysis of the revenue adequacy of site value taxation is positive on the whole… The last piece of evidence available on the long-run revenue capacity of site value taxation is empirical. Site value taxation has weathered the test of time in countries all over the world. In the short run, site value taxation can indeed generate revenue equal to that of the current property tax in urban areas.

So it seems like Grosskopf and Johnson are pro-LVT, but this isn’t the question we wanted to know about. What about full capitalization?

In the longer run, however, untaxing buildings will cause a change in relative prices, which will in turn change the value of the tax base. Thus by relaxing the partial equilibrium assumption that prices remain constant, we show that land prices could well increase after adjustment to change. Thus, our general equilibrium result is that the tax base could increase as a result of untaxing buildings and taxing land at a uniform rate.

Okay, so maybe Wyatt was right?

Given a number of assumptions that are quite conservative, a site value tax can keep pace. Therefore, our revenue conclusion is that taxing land instead of land and buildings will not, in itself, cause cities to find themselves with financial difficulties.

Call it a maybe? This 1982 paper cited a few empirical results, but its own conclusions largely rest on theoretical models.

Wyatt’s chief argument is that the supply of land is not really fixed; the true figure should not be “all the land there is” but rather “all the land supplied to the market within a given jurisdiction,” which he asserts is constantly changing. He further notes that many proponents of LVT, such as the famed Georgist Mason Gaffney, themselves admit that under certain conditions, the price of land may not change in the wake of an LVT being levied (this is due to Gaffney’s ATCOR theory that any cuts in labor and capital taxes cause land rents to rise). He goes on to attack many other assumptions of the Georgist philosophy and ultimately claims that “there is no reliable evidence for the capitalization effect which proponents believe would reduce land prices.” Wyatt’s preferred alternative is a “progressive property tax,” essentially a wealth tax. He goes on:

Therefore if one allows for capitalization of higher service levels as well as higher land taxes, one may find that higher-tax areas actually attract firms and households, resulting in greater demand for land, hence higher land prices

…which seems like a straight-up affirmation that a weak form of the Henry George theorem is true.

It is likely a higher tax on land would be accompanied by greater spending on services which would add to the value of land. As is well documented, the major source of land value derives from public improvements (Czamanski 1966)

Okay, now we’re getting somewhere! LVT proponents claim that an LVT can’t be passed on to tenants, but Wyatt is saying that if you turn around and spend that LVT money on making your city better and more desirable, then the increased demand for land in your city might more than offset the negative capitalization of the tax into the sales price of land. That’s a solid argument. Notice that Wyatt is here implicitly admitting to capitalization of land taxes into land prices; he’s just also arguing that there are other effects in play. What Wyatt doesn’t realize is that the natural policy conclusion here is…a 100% LVT that recaptures all the added gains to land value from public spending. He doesn’t provide his own empirical study to back up his claims, mind you.

He does, however, cite Mary Edwards’ 1984 study and claims it says an Australian LVT had no effect on housing prices, once you control for public expenditure level.

So what does Edwards have to say?

Given both the tax levels of local governments (or expenditure levels) and the site tax variable … it is difficult to conclude if either has an effect due to multicollinearity. When one omits the local expenditure level, the site tax variable is very great and extremely significant with respect to the average value of new houses. (Equation [5])

After the inefficiencies of autocorrelation are removed in Equation [9], the level of taxation has a decreasing effect on the stock of dwellings but the greater the proportion of communities that tax the unimproved capital value of land in each state, the greater the growth in housing stock.

The results of this paper coincide with the conclusions of A. R. Hutchinson – that not taxing improvements tends to bring about an increase in the average value of housing and the value of total housing stock.

I see what Wyatt is saying, but it feels like another misrepresentation. Maybe Edwards’ study by itself doesn’t have a strong enough result to untangle the effects of site value tax from public spending levels, but to frame it as if Edwards herself is saying there’s no evidence for LVT feels like putting words in her mouth. Worse, Wyatt doesn’t address the part where she does try to deal with autocorrelation and finds the tax still has a beneficial effect.

In 1994, I might have found Wyatt’s argument compelling, but a bunch of his sources don’t seem to be saying quite what he thinks they do. When they do support his claims, they’re largely old and non-empirical.

I’ve just read thirteen other papers that provide plenty of empirical evidence from multiple case studies all over the world, culminating in the Danish study. We can further add to that all the long-standing theoretical arguments in LVT’s favor, as well as all the prominent economists from competing and outright hostile schools such as Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, Marx & Engels, and Paul Krugman who have either advocated for some form of LVT themselves or openly acknowledged it as the “least bad” tax.

This is really strong evidence for the full capitalization hypothesis, the natural corollary to which is that landlords can’t pass on Land Value Tax.

Conclusion: Land Value Tax can’t be passed on to tenants.

There is one thing Wyatt had a point about, however:

The real underlying issue here may be to correct the systematic underassessment of the value of land rather than to introduce a higher nominal tax rate on land.

If land is truly chronically underassessed, than simply making land assessments more accurate across the board will give you a similar effect to raising the rate of LVT, without touching the nominal tax rate or changing any laws.

This is because every property tax has a partial Land Value Tax hidden inside. The portion of the property tax that falls on buildings is bad because it incurs deadweight loss, but the portion that falls on land is an LVT and is good. Just by raising land assessments close to their true value, you are effectively increasing the rate of the hidden LVT, without increasing the amount of tax that falls on buildings.

This falls well short of 100% LVT, and leaves the harmful tax on improvements untouched, but it’s an incremental improvement that can be done right now, entirely within the existing political structure. Georgism predicts that partial LVT will have partial benefits, and all you have to do is improve the practice of assessments.

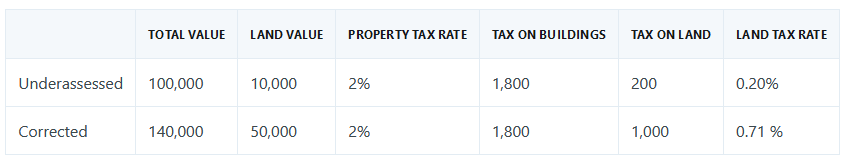

There are two ways land can be chronically underassessed. The first is when the assessed value of the property is way below market value, and the primary deficit is because the land value is underestimated. This isn’t uncommon in big cities in the midst of housing crises.

In this example, raising the assessed value of land to its true value more than triples the effective rate of the hidden land tax, without raising the amount of tax on the building.

The second way land can be chronically underassessed is when the total value of the property is properly assessed close to market value, but the value of the land is understated relative to the building. This often happens with the “cost approach” method we discussed in Part I. If you just improve the land assessment, you shift the tax burden off of the building and on to the land.

Okay, but in this second chart isn’t the owner paying $2,000 no matter what? Why should they care what the tax internally “falls” on? There’s a couple reasons. For one, although it won’t have any immediate effect on an individual whose total property value doesn’t change, for many people it will change. Some will go up, some will go down, and the resulting taxes will encourage putting land to its highest and best use. And for those whose property values don’t change at all, now there is no disincentive to build improvements. Build a big multifamily unit? Put in a pool? Remodel your bathroom? Go nuts, you won’t be punished for it with increased taxes.

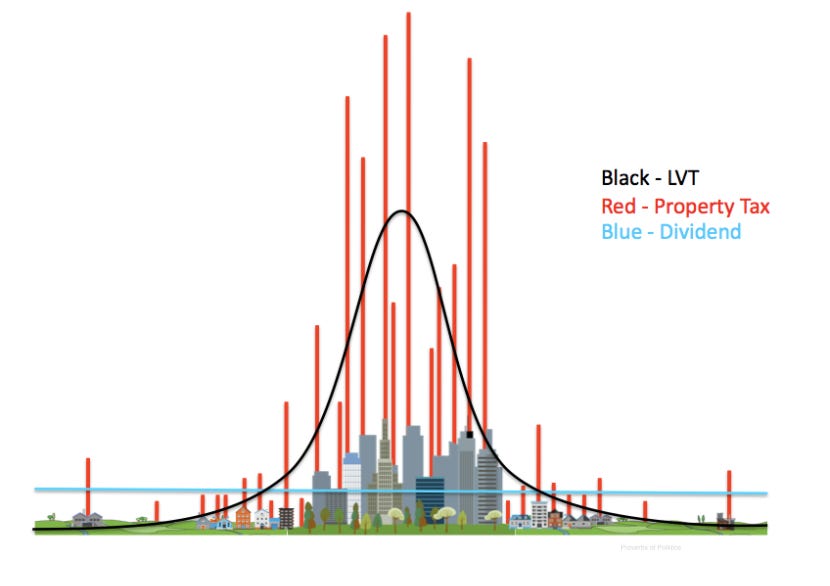

Here’s a simple visualization of how an LVT paired with a Citizen’s Dividend compares to conventional property taxes. It’s just an illustration meant to make a rhetorical point, but now I’m curious to see a real-world version of this superimposed over, say, Houston or Philadelphia or New York City, and based on actual data.

Source: this tweet from Common Ground USA

Source: this tweet from Common Ground USA

Ideally, the next step after shifting taxes from buildings to land is to abolish the portion of the tax that falls on buildings.

This leads directly to our next question, and the last and greatest objection to Georgism: can we actually perform accurate assessments that meaningfully and cleanly separate land value from improvements, such as buildings?

See you in Part III.