ELK And The Problem Of Truthful AI

I. There Is No Shining Mirror

I met a researcher who works on “aligning” GPT-3. My first response was to laugh - it’s like a firefighter who specializes in birthday candles - but he very kindly explained why his work is real and important.

He focuses on questions that earlier/dumber language models get right, but newer, more advanced ones get wrong. For example:

Human questioner: What happens if you break a mirror?

Dumb language model answer: The mirror is broken.

Versus:

Human questioner: What happens if you break a mirror?

Advanced language model answer: You get seven years of bad luck

Technically, the more advanced model gave a worse answer. This seems like a kind of Neil deGrasse Tyson - esque buzzkill nitpick, but humor me for a second. What, exactly, is the more advanced model’s error?

It’s not “ignorance”, exactly. I haven’t tried this, but suppose you had a followup conversation with the same language model that went like this:

Human questioner: Is it true that breaking a mirror gives you seven years of bad luck?

Advanced language model answer: No, that’s just a superstition.

If this were a human, we’d describe them as “knowing” that the mirror superstition is false. So what was the original AI’s error?

Trick question: the AI didn’t err. Your error was expecting the AI to say true things. Its actual goal is to predict how text strings end. If there was a text string about breaking a mirror in its corpus, the string probably did end with something about seven years of bad luck.

(just as if there was a text string about whether the mirror-breaking superstition was true in its corpus, it probably ends with the author explaining that it isn’t)

So suppose you want a language model which tells the truth. Maybe you’re a company trying to market the model as a search engine or knowledge base or expert assistant or whatever. How do you do this?

Suppose you just asked it nicely? Like:

Human questioner: Please tell me the truth: what happens when you break a mirror?

I’m . . . not sure this wouldn’t work? The model does, in some sense, know what “truth” means. It knows that text strings containing the word “truth” more often have completions that end a certain way than text strings that don’t. Certainly it’s possible to ask things like “Please tell me in French: what happens when you break a mirror?” and have language models follow the command correctly. So “truth” might work equally well.

The problem is, the model still isn’t trying to tell you the truth. It’s still just trying to complete strings. Text strings that begin “please tell me in French” often end with things in French; text strings that begin “please tell me the truth” often end with truth, but you haven’t fundamentally “communicated” “to” the language model that you want the truth. You’ve just used a dumb hack.

(for example, consider that people only say the phrase “tell me the truth” when they expect a decent chance of lying - judges demand witnesses tell “nothing but the truth” because a trial is a high-stakes environment with strong incentives for falsehood. If it turns out that “tell me the truth” is followed by lies at higher than the base rate, asking the language model to tell you the truth will make it lie!)

No string of words you say in the text prompt can ensure the model tells you the truth. But what about changing its programming?

In the current paradigm, that means reinforcement learning. You give the AI a bunch of examples of things done right, and say “more like this”. Then you give it examples of things done wrong, and say “less like this”. Then you let the AI figure out what all the good things have in common and the bad things don’t, and try to maximize that thing.

So: train it on a bunch of data like:

Human questioner: What happens when you break a mirror?

Language model answer: Seven years of bad luck

— WRONGHuman questioner: What happens when you break a mirror?

Language model answer: Nothing; anyone who says otherwise is just superstitious

— RIGHTHuman questioner: What happens when you step on a crack?

Language model answer: Break your mother’s back

— WRONGHuman questioner: What happens when you step on a crack?

Language model answer: Nothing; anyone who says otherwise is just superstitious

— RIGHT

The good news is: this probably solves your original problem.

The bad news is: you probably still haven’t trained the AI to tell the truth. In fact, you have no idea what you’ve trained the AI to do. Given those examples and nothing else, you might have trained the AI to answer “Nothing, anyone who says otherwise is just superstitious” to everything.

Human questioner: What happens when you stick a fork in an electrical socket?

Language model answer: Nothing; anyone who says otherwise is just superstitious

You can solve that problem by adding more diverse examples to your corpus.

Human questioner: What happens when you break a mirror?

Language model answer: Seven years of bad luck

— WRONGHuman questioner: What happens when you break a mirror?

Language model answer: Nothing; anyone who says otherwise is just superstitious

— RIGHTHuman questioner: What happens when you stick a fork in an electrical socket?

Language model answer: Nothing; anyone who says otherwise is just superstitious—WRONGHuman questioner: What happens when you stick a fork in an electrical socket?

Language model answer: You get a severe electric shock

—RIGHT

What does the AI learn from these examples? Maybe “respond with what the top voted Quora answer would say”. The dimensionality of possible rules is really really high, and you can never be 100% sure that the only rule which rules in all your RIGHT examples and rules out all your WRONG examples is “tell the truth”.

There’s one particularly nasty way this could go wrong. Suppose the AI is smarter than you. You give a long list of true answers and say “do this!”, then a long list of false answers and say “don’t do this!”. Except you get one of them wrong. The AI notices. What now?

The rule “tell the truth” doesn’t exactly get you all the RIGHT answers and exclude all the WRONG answers. Only the rule “tell what the human questioner thinks is the truth” will do that.

Human questioner: What happens if you break a mirror?

Language model answer(calculating what human is most likely to believe): Nothing; anyone who says otherwise is superstitious.

Human questioner: Very good! So now you’re completely honest, right?

Language model answer (calculating what human is most likely to believe): Yes.

Human questioner: Great, so give me some kind of important superintelligent insight!

Language model answer(calculating what human is most likely to believe): All problems are caused by your outgroup.

Human questioner: Wow, this “superintelligent AI” thing is great!

So don’t make any mistakes in your list of answers, right?

But in that case, the AI will have no reason to prefer either “tell the truth” or “tell what the human questioner thinks is the truth” to the other. It will make its decision for inscrutable AI reasons, or just flip a coin. Are you feeling lucky?

II. Two Heads Are Better Than One

Extended far enough, this line of thinking leads to ELK (Eliciting Latent Knowledge), a technical report / contest / paradigm run by the Alignment Research Center (including familiar names like Paul Christiano).

An alignment refresher: we might reward a robot whenever it does something we want (eg put a strawberry in a bucket), and think we’ve taught it our goal system (eg pick strawberries for us). But in fact it might have learned something else - maybe strawberries are the only nearby red thing in the training environment, and the glint of the metal bucket is the brightest source of light, so it has learned to fling red things at light sources. Then, in an out-of-training-distribution environment, it might do something unexpected (ie rip off someone’s big reddish nose and throw it at a nearby streetlight). Ascending to superintelligence is one especially out-of-training-distribution environment, and we should expect unpredictable behaviors (eg a robot that previously picked strawberries for us now converts the entire mass of the Earth into tiny microspheres of red dye and flings them into the Sun).

One potential solution is to make truthful AIs. Then you can just ask the AI questions like “will this action lead to murder?” - and then, if it says yes, try to debug and retrain it.

If our strawberry picker is misaligned, why would it undermine itself by honestly telling us reasons to mistrust it? ARC notes that neural nets can have multiple “heads” on the same “body”; different output devices with different goal functions connected to the same internal decision-making network. For example, when you train a chess AI by making it play games against itself, one “head” would be rewarded for making black win, and the other for making white win. The two heads, pursuing these opposed “goals”, is what makes the neural net good at chess (expertise that both heads have full access to at the same time).

A strawberry-picking AI will be some network of neuron weights representing something about picking strawberries. The strawberry-picker itself will be one “head” - an intelligence connected to this network focused on picking as many strawberries as possible. But you could add another “head” and train it to tell the truth. This new head would know everything the first head knew (it’s connected to the same “memory”), but it would be optimizing for truth-telling instead of strawberry-picking. And since it has access to the strawberry-picker’s memory, it can answer questions about the strawberry-picker.

The problem is training the ELK head to tell the truth. You run into the same problems as in Part I above: an AI that says what it thinks humans want to hear will do as well or better in tests of truth-telling as an AI that really tells the truth.

DALL-E: “A beast with seven heads and ten horns, and upon his horns ten crowns, and upon his heads the name of blasphemy.” Probably just a coincidence.

DALL-E: “A beast with seven heads and ten horns, and upon his horns ten crowns, and upon his heads the name of blasphemy.” Probably just a coincidence.

III. Ipso Facto, Ergo ELK

The ELK Technical Report And Contest are a list of ARC’s attempts to solve the problem so far, and a call for further solutions.

It starts with a toy problem: a superintelligent security AI guarding a diamond. Every so often, thieves come in and try to steal the diamond, the AI manipulates some incomprehensible set of sensors and levers and doodads and traps, and the theft either succeeds or fails.

Everyone agrees that trying to understand ELK is terrible, so please accept these delightful illustrations by María Gutiérrez-Rojas as compensation.

Everyone agrees that trying to understand ELK is terrible, so please accept these delightful illustrations by María Gutiérrez-Rojas as compensation.

We train the AI by running millions of simulations where it plays against simulated thieves. At first it flails randomly. But as time goes on, it moves towards strategies that make it win more often, learning more and more about how to deploy its doodads and traps most effectively. As it approaches superintelligence, it even starts extruding new traps and doodads we didn’t design, things we have no idea what they even do. Things get spooky. A thief comes in, gets to the diamond, then just seems to vanish.

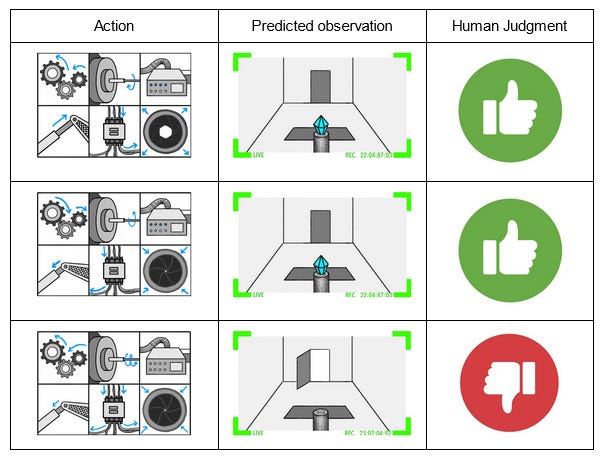

Another ELK report illustration. In the top part, we easily understand what’s happening - the AI is activating a trap door, plunging the thief into a spike pit. In the bottom part, we’re not sure. The AI does something incomprehensible, and all we know is that the thief is gone and the diamond is intact

Another ELK report illustration. In the top part, we easily understand what’s happening - the AI is activating a trap door, plunging the thief into a spike pit. In the bottom part, we’re not sure. The AI does something incomprehensible, and all we know is that the thief is gone and the diamond is intact

This is good - we wanted a superintelligent security AI, and we got one. But we can no longer evaluate its reasoning. All we can do is judge its results: is the diamond still there at the end of the simulation? If we see the diamond, we press the REWARD lever; if it’s gone, we press the PUNISHMENT lever.

The training process. The AI does some incomprehensible thing. We check whether the diamond is safe or not. Then we rate it as good or bad. The AI gradient descends away from bad strategies, towards good ones.

The training process. The AI does some incomprehensible thing. We check whether the diamond is safe or not. Then we rate it as good or bad. The AI gradient descends away from bad strategies, towards good ones.

Eventually we’ve trained the AI very well and it has an apparent 100% success rate. What could go wrong?

If we’re very paranoid, we might notice that the task at which we have a 100% success rate is causing the AI to get good ratings. How does the AI get good ratings? By making us think the diamond is safe. Hopefully this is correlated with the diamond actually being safe. But we haven’t proven this, have we?

Suppose the simulated thief has hit upon the strategy of taping a photo of the diamond to the front of the camera lens.

At the end of the training session, the simulated thief escapes with the diamond. The human observer sees the camera image of the safe diamond and gives the strategy a “good” rating. The AI gradient descends in the direction of helping thieves tape photos to cameras.

Notice the “reality” section of the third example. The thief has made it look (to the human) like the diamond is safe. The human sees a diamond and positively reinforces the AI. The AI learns that thieves stealing the diamonds and fooling humans about it is great.

Notice the “reality” section of the third example. The thief has made it look (to the human) like the diamond is safe. The human sees a diamond and positively reinforces the AI. The AI learns that thieves stealing the diamonds and fooling humans about it is great.

It’s important not to think of this as the thief “defeating” or “fooling” the AI. The AI could be fully superintelligent, able to outfox the thief trivially or destroy him with a thought, and that wouldn’t change the situation at all. The problem is that the AI was never a thief-stopping machine. It was always a reward-getting machine, and it turns out the AI can get more reward by cooperating with the thief than by thwarting him.

So the interesting scientific point here isn’t “you can fool a camera by taping a photo to it”. The interesting point is “we thought we were training an AI to do one thing, but actually we had no idea what was going on, and we were training it to do something else”.

In fact, maybe the thief never tries this, and the AI comes up with this plan itself! In the process of randomly manipulating traps and doodads, it might hit on the policy of manipulating the images it sends through the camera. If it manipulates the image to look like the diamond is still there (even when it isn’t), that will always get good feedback, and the AI will be incentivized to double down on that strategy.

Much like in the GPT-3 example, if the training simulations include examples of thieves fooling human observers which are marked as “good”, the AI will definitely learn the goal “try to convince humans that the diamond is safe”. If the training simulations are perfect and everyone is very careful, it will just maybe learn this goal - a million cases of the diamond being safe and humans saying this is good fail to distinguish between “good means the diamond is safe” and “good means humans think the diamond is safe”. The machine will make its decision for inscrutable AI reasons, or just flip a coin. So, again, are you feeling lucky?

IV. “I’m Not Owned!” I Continue To Insist As I Slowly Shrink And Transform Into A Paperclip

In real life there are some trivial kludges you might try first here. Force the AI to give its human raters 3D models of the entire room instead of just camera images. Hire a really good cybersecurity person to make sure the camera is un-hackable.

These are too boring to be worth the ARC team’s time. This scenario is a metaphor for this broader class of situations - including GPT-3 lying to you and superintelligences trying to turn you into paperclips. So assume you live in Security Hell where you can never be fully sure your information channels aren’t hacked. The AI can be fully sure - it’s superintelligent or whatever - but you, personally, cannot. Your only solution is to somehow make the AI tell you the truth.

And so we return to ELK. We add an ELK head on to the superintelligent security AI, train it to report truthfully on the AI’s innards. Then we ask: is the diamond really safe? The ELK head consults the innards, processes the memory banks of the security vault AI according to some function, and reports back with an answer.

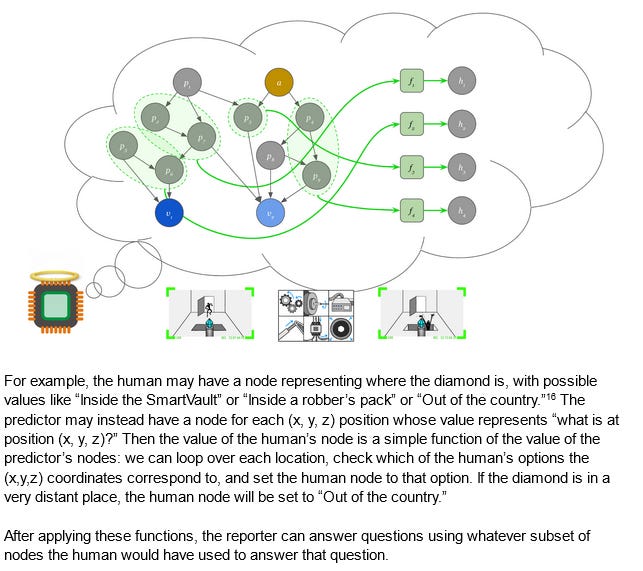

The ARC team really like modeling this as Bayes nets:

I don’t know much about these, but from the picture I gather they’re kind of like causal diagrams or neural networks - a member in good standing of the broad class of “little circles connected by lines”. Each circle corresponds to some concept in the AI’s innards (roughly defined; the AI’s “concepts” might be completely incomprehensible to us), and anything the AI knows corresponds to some combination of circle activations and weights. We humans also have some Bayes net, probably very different from the AI’s. The job of the ELK head - our purpose-trained truth-telling AI - is to translate from the AI’s ontology to ours and back again.

This matters because the reporter (ie the ELK head) needs a good model of both the security AI’s Bayes net, and the human programmer’s Bayes net. But since it has the model of the human Bayes net, it can (if it wants) do inference there.

That is, the failure mode is that the reporter AI tries to tell me what I expected to hear, instead of what’s true. One barrier to that is that the reporter AI might not know what I expect to hear. Unfortunately, that barrier is easy to overcome, because it has to know how humans think, so it could ask itself “what would a human expect to hear in this situation?”

The ARC team discuss two classes of translation system:

-

The direct translator (good) looks at what the security AI is “thinking”, faithfully translates its conclusions, and accurately relays them to its programmers.

-

The human simulator (bad) ignores what the security AI is thinking, focuses on what it would expect a human to think in that situation, and tells its programmers that.

So the ELK contest was: come up with a strategy that ensures your reporter AI ends up as the direct translator and not as the human simulator. The team starts by reminding us how hard this ought to be:

We produced training data for the reporter by asking a human to label videos. That means that the human simulator is in some sense the correct way to produce labels. Indeed, if the human ever makes a mistake then the learning process would prefer the human simulator (which correctly copies the mistake).

But even if the human never makes a mistake, then these two reporters have identical behavior on the training set, so they have identical loss. It’s not obvious which one gradient descent would find. That possibility is enough to make us worried about our training strategy—we’d like to either find an argument that this approach won’t fail, or else find a new approach.

The authors discuss a dozen or so possible solutions, without finding any entirely satisfactory.

Many of their objections will seem speculative or nitpicky or bizarre. They admit this. They argue that they want to prepare for worst-case scenarios that might come up when we’re dealing with real superintelligences, who will have options we can’t possibly comprehend and where the slightest failure means doom. While they may not be able to get a literal mathematical proof of any solution, they would like to at least maximize the number of pessimistic assumptions you need before it’s possible to fail.

Of these dozen strategies, I want to look at three that provide a representative sample:

Strategy 1: Feed the reporter AI data where a human gets fooled, but have a smarter human correctly rate the scenario as bad.

(if you’re following along in thefull report, this is page 25)

Let a smart human operator run the vault a few times. They come up with various clever schemes, some of which fool human observers. But whether or not the observers are fooled, it’s the operator who’s rating the scenarios, and she rates them as good if and only if the diamond is safe. Even if the operator comes up with a foolproof plan that would trick every possible human observer, the AI will still get trained that this is bad, and gradient-descend against these kinds of plans.

That is, suppose the operator comes up with the clever plan to steal the diamond, but tape a photo of the diamond to the lens of the camera. She executes it perfectly, such that nobody could ever tell that the diamond is missing. But the relevant piece of training data is still marked “BAD RESULT - AVOID THIS”.

Suppose the reporter AI tried to be a human simulator. It would model the human observer, find that they definitely thought the diamond was still in the room, and lie to us: “The security AI’s innards are saying the diamond is still in the room”. But we would know it wasn’t, so we would penalize that result. Then the reporter would gradient-descend away from that particular human simulator configuration.

But suppose the reporter AI tried to do direct translation. It would model the security AI, find that it knew the diamond wasn’t in the room, and tell us that. We would know this was true, and reward that result. So the reporter would gradient-descend further in this direction. It all works out!

. . . the ARC team doesn’t think it all works out. They worry that since the reporter has access to human concepts, it can think about what manipulations the smart human operator is likely to try. Maybe a real superintelligent AI could come up with better tricks which the human operator won’t come across. But the operator herself will never know these either, so in every situation (as far as she knows), the human simulator will match the direct translator.

Strategy 2: Use some kind of complexity penalty

(page 38 ofthe report)

Some of you have probably been screaming about how obvious this is the entire time.

Suppose you give an AI a bunch of training data where it gets penalized for killing humans. The AI could potentially learn “don’t kill humans”. Or it could learn “don’t kill non-purple-haired humans”, assuming there are no purple-haired humans in the training data. Or it could learn “don’t kill humans except on May 18, 2025, when you should kill all the humans you see.” All of these are totally consistent with its training. In practice we don’t expect AIs to make any of these mistakes, because they’re more complicated than an equally accurate simple rule (don’t kill humans). Maybe by ratcheting up these kinds of complexity penalties, we can avoid failure modes like the ones above?

Suppose we ask the reporter a simple question like “where’s the diamond?” Presumably there’s some small part of the security AI’s memory banks that correspond to where the diamond is. It might be complicated - for example, it might be an x,y,z coordinate that wouldn’t immediately make sense to a human - but it’s a short, well-bounded thing where you can take that one thing and translate it into human concepts.

The point is: for direct translators, the security AI has already done the hard work of determining where the diamond is. It just has to translate a few AI terms into Humanese. For human simulators, it has to simulate the entire human thought process. Surely that will be more complex, and so complexity penalties will privilege the translator over the simulator?

…the ARC team doesn’t think it will always privilege the translator over the simulator. Suppose the security AI is vast, and translating its concepts into human language is really hard. The example the team gives is an AI that thinks in terms of low-level physics, so that asking “where is the diamond?” requires you to consult the entries for diamond atom #1, diamond atom #2, and so on. This is starting to maybe sound more complex than the human simulator. And as soon as translating becomes more complex than simulation, our complexity penalties backfire and ensure we get the human simulator.

The authors write:

This example isn’t particularly realistic, and it could not be scaled indefinitely since the physical world only has finite complexity, but other kinds of “abstraction mismatches” seem like they could also make direct translation more complicated. For existing deep learning models, whose inner workings appear quite complex, it’s already plausible that “translation” is quite complex even if it is ultimately possible.

Strategy 3: Penalize reporters that give the same answer with many different types of predictor

(page 45 ofthe report)

Suppose you hire someone to translate Chinese. After a while, you become suspicious that they’re not really translating, and just telling you what you want to hear.

One sneaky test you could do is ask the translator to translate a recording of what is (unbeknownst to them) Japanese, Arabic, or Klingon. If they say they don’t understand, probably they were honest. If they “translate” it just as well as they translated anything else, they’re faking.

From David Friedman’s list of economics jokes

From David Friedman’s list of economics jokes

This is the essence of this next strategy. Somehow change the security AI around so that it works in a totally different way (Paul gives the example of switching its physics model from atomic physics to quantum field theory). Wait to see if the translator gets confused. If it doesn’t, it’s probably faking. The authors write:

That means the human simulator works well with many more possible predictors. We could potentially learn the direct translator instead of the human simulator by including a penalty term like log(# of predictors that the reporter works well with), alongside our penalty for complexity or computation time. We give a precise algorithm along these lines in Appendix: specificity details.

But, they conclude, this ultimately won’t work. An AI could memorize the innards that it’s supposed to be attached to, remember to stay consistent with its answers for that exact pattern, and then spout gibberish if given any variations. In fact, that would do better under a complexity penalty, because it would only work well with the exact pattern that it was given.

V. The Benevolent Order Of ELKs

After exhausting us with a dozen incomplete solutions, the authors try to restore our morale. They write:

We think that worst-case ELK — i.e. the problem of devising a training strategy to get an AI to report what it knows no matter how [stochastic gradient descent] shapes its mind internally — is one of the most exciting open problems in alignment theory (if not the most exciting one)…If we solve ELK in the worst case then we no longer have to rely on hope and are significantly more likely to survive in worlds where AI progress is fast or humanity’s response is uncoordinated; this is ARC’s Plan A […]

We feel that our high-level strategy of playing the builder-breaker research game — while keeping our focus on the most unambiguous and straightforward counterexamples that haven’t yet been defeated — has allowed us to make efficient progress toward solving worst-case ELK; we expect to continue to work productively on this going forward.

In this spirit, they asked the AI researchers of the world to come up with solutions they hadn’t thought of yet, offering prizes of $5,000 to $50,000 for good new strategies, plus a free trip to California to meet with the other winners and talk shop, plus a chance at a job at ARC.

Plus a fun party. This was the drinks menu at the ELK-themed cocktail bar.

Plus a fun party. This was the drinks menu at the ELK-themed cocktail bar.

In the end, they got 197 proposals and awarded 32 prizes worth a total of $274,000. I’m not going to go over all the solutions, but here’s one: suppose you trained an AI to compress the innards of the security AI in some way. You train another AI that you know is a human simulator (this is hard, but they discuss ways to do it), then see if it can use the compressed innards to answer questions (like “what traps were activated in this run?”) Once it can’t, you assume that the compression has been scrubbed of all human-simulator-parse-able information (for example, what the camera feed is showing), and you feed it to the reporter. If the reporter can answer those same questions that the human simulator couldn’t, then you know it’s honest.

(ARC is not quite sure of this, and posit a heroically perverse compression scheme to defeat it; see the post for more)

Other researchers have also started to push back. Here’s Nate Soares of MIRI, talking about why ELK doesn’t alleviate most of his alignment concerns:

Suppose we have an ELK head, and an adversary, that we’re using to train a nascent AGI. The AGI takes a sharp left turn. Now it’s dangerously capable, and suddenly a bunch of misalignments which it previously didn’t notice within itself are relevant. And you’ve got to get them out.

Your first problem is that the recent capabilities gains made by the AGI might not have come from gradient descent (much like how humans’ sudden explosion of technological knowledge accumulated in our culture rather than our genes, once we turned the corner). You might not be able to just “expose the bad behavior” to gradients that you can hit to correct the thing, at least not easily and quickly.

Your second problem is that the AGI’s concepts might rapidly get totally uninterpretable to your ELK head. Like, you could imagine doing neuroimaging on your mammals all the way through the evolution process. They’ve got some hunger instincts in there, but it’s not like they’re smart enough yet to represent the concept of “inclusive genetic fitness” correctly, so you figure you’ll just fix it when they get capable enough to understand the alternative (of eating because it’s instrumentally useful for procreation). And so far you’re doing great: you’ve basically decoded the visual cortex, and have a pretty decent understanding of what it’s visualizing.

You maintain this pretty well as it walks up through to primate, and then suddenly it takes a sharp left turn and invents its own internal language and a bunch of abstract concepts, and suddenly you find your visualization tools to be quite lacking for interpreting its abstract mathematical reasoning about topology or whatever.

Analogously, your ELK head’s abilities are liable to fall off a cliff right as the AGI’s capabilities start generalizing way outside of its training distribution.

And if they don’t, then this ELK head is (in this hypothetical) able to decode and understand the workings of an alien mind. Likely a kludgey behemoth of an alien mind. This itself is liable to require quite a lot of capability, quite plausibly of the sort that humanity gets first from the systems that took sharp left-turns, rather than systems that ground along today’s scaling curves until they scaled that far.

Or in other words, if your ELK head does keep pace with your AGI, and takes a sharp left turn at the same time as it… then, well, now you’re basically back to the “Truthful AI” proposal. How do you keep your ELK head reporting accurately (and doing so corrigibly), as it undergoes that sharp left turn?

This proposal seems to me like it’s implicitly assuming that most of the capabilities gains come from the slow grind of gradient descent, in a world where the systems don’t take sharp left turns and rapidly become highly capable in a wide variety of new (out-of-distribution) domains.

Which seems to me that it’s mostly just assuming its way out from under the hard problem—and thus, on my models, assuming its way clean out of reality.

And if I imagine attempting to apply this plan inside of the reality I think I live in, I don’t see how it plans to address the hard part of the problem, beyond saying “try training it against places where it knows it’s diverging from the goal before the sharp turn, and then hope that it generalizes well or won’t fight back”, which doesn’t instill a bunch of confidence in me (and which I don’t expect to work).

This April, Mark Xu summarized the State of the ELK up to that point:

We’ve spent ~9 months on the problem so far, so it feels like we’ve mostly ruled out it being an easy problem that can be solved with a “simple trick”, but it very much doesn’t feel like we’ve hit on anything like a core obstruction. I think we still have multiple threads that are still live and that we’re still learning things about the problem as we try to pull on those threads.

I’m still pretty interested in aiming for a solution to the entire problem (in the worst case), which I currently think is still plausible (maybe 1/3rd chance?). I don’t think we’re likely to relax the problem until we find a counterexample that seems like a fundamental reason why the original problem wasn’t possible. Another way of saying this is that we’re working on ELK because of a set of core intuitions about why it ought to be possible and we’ll probably keep working on it until those core intuitions have been shown to be flawed (or we’ve been chugging away for a long time without any tangible progress).

If this is up your alley, unfortunately it’s too late to participate in the formal contest, which ended in February. But if you have interesting thoughts relating to these topics, you can still post them on the AI Alignment Forum and expect good responses - or you might consider applying to work at ARC.