Failure To Replicate Anti-Vaccine Poll

I.

Steve Kirsch is an inventor and businessman most famous for developing the optical mouse. More recently, he’s become an anti-COVID-vaccine activist. He has many different arguments on his Substack, of which one especially caught my eye:

He got Pollfish, a reputable pollster, to ask questions about people’s COVID experiences, including whether they thought any family members had died from COVID or from COVID vaccines. Results here:

-

7.5% of people said a household member had died of COVID

-

8.5% of people said a household member had died from the vaccine.

All other statistics were normal and confirmed that this was a fair sample of the population. In particular, about 75% were vaccinated (suggesting that they weren’t just polling hardcore anti-vaxxers).

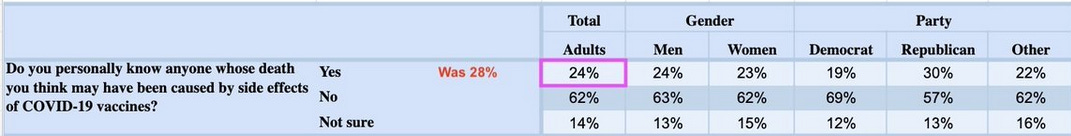

Since then, Kirsch has collected several other polls - some by him, some by others - saying the same. For example, here’s Rasmussen (another reputable polling company) from last January:

I’ve truncated the table to keep it readable, but I kept the breakdown by party - these aren’t just anti-vax Republicans lying to support their party narrative. Even 19% of Democrats say they know someone killed by the vaccine!

I know people here like to argue about whether to debate people or deplatform them, but surely someone else finds this interesting. Here’s 24% of the US - so probably a little short of 100 million people - saying they’ve seen something which consensus science says shouldn’t be possible? Aren’t you at least a little curious what’s going on?

Also, isn’t Steve Kirsch being a little too smug about this?

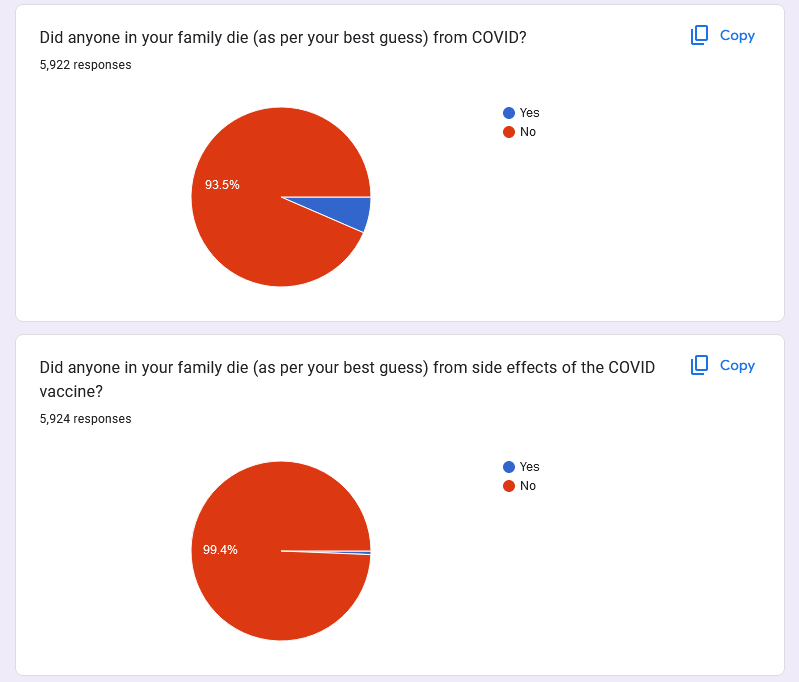

So I asked about this on the 2022 and 2024 ACX surveys. Both gave similar results, but I’m going to focus on the 2024 survey, since I did the most followup on it.

Here “family” was defined on the question page as including “brother, sister, mother, father, child, aunt, uncle, grandparent, grandchild, niece, or nephew”. This is broader than Pollfish’s “member of your household” but narrower than Rasmussen’s “person you know”.

Kirsch and I got similar results for knowing someone who died of COVID - 6.5% vs. 7.5%. But we got very different results for knowing someone who died from the vaccine: Kirsch’s 8.5% vs. my 0.6%. Why?

As people love to point out, my survey is a nonrepresentative sample. But as I point out, it’s important to keep track of when that should vs. shouldn’t matter. No matter how weird my readers are, they’re not biologically invincible - they should have side effects at similar rates to anyone else.

One possibility is that my readers are very pro-vaccine compared to the general population, so they interpret ambiguous cases in a more pro-vaccine way. I didn’t have a question about vaccine-related views, but it’s no secret that vaccine opponents are more often right-wing, so I looked at questions about politics.

Conservatives in general were only slightly more likely (1%) to report vaccine deaths compared to liberals (0.4%).

But I had a question where people ranked their support for Donald Trump from. Trump supporters had much higher vaccine injury rates (7.5%) than moderates (1.3%) or opponents (0.3%).

I couldn’t find much of an effect by gender, education level, or any of the other traditional demographic categories.

This doesn’t quite explain the difference between my survey and the others, since my moderates had 1.3% side effect rate, and the Rasmussen moderates had 22%. But it does suggest that there’s room for political beliefs to alter perception of relatives’ vaccine deaths.

II.

All of this would be much clearer if we could get in there and ask the people who said their relatives died from vaccines what they meant. Most ACX Survey respondents gave me permission to email them. So I emailed the people who answered “yes” to that question and asked for their story. Some details:

-

5,981 people took the survey

-

5,924 of them answered the question on COVID vaccines

-

38 of them answered “yes” to that question

-

28 of them gave me their email and permission to contact them.

-

9 of them answered my email and told their stories.

Of the nine people who answered my email, three said they’d read the question wrong and wanted to retract their answer, leaving six people who gave me real stories. I’m slightly obfuscating some of these to protect their privacy:

-

80 year old went to the hospital after a stroke, received the Pfizer vaccine there, then got sicker and died two weeks later. The respondent said their relative “was already in bad health either way, so it’s hard to place blame on the vaccine, but I do think it contributed - she had been recovering before getting it.”

-

95 year old got the Moderna vaccine, that night she started vomiting and wouldn’t eat, and after 3-4 days she died. The respondent said “I think nobody in the family thought it was a mistake to do the vaccination, as [a COVID infection] would probably have [also killed her].”

-

A 63 year old died of a heart attack six weeks after his booster vaccination. He had a previous history of heart attacks, but had been declared healthy before the vaccine.

-

An 83 year old died the night after getting a COVID booster. She had some previous health conditions “but she wasn’t knocking on death’s door”. The respondent writes “[I think] the side effects were probably just too much for her somewhat fragile state to handle…most of my family believes it was the vaccine, but that the vaccines are overall a net positive for both us and society.”

-

A 37 year old with extreme obesity had a heart attack one day after a COVID mRNA booster.

-

A 94 year old, one week after getting the vaccine, went to the hospital due to heart failure and UTI. He tested positive for COVID and died after admission.

Four out of six cases are ≥ eighty years old. Since I only heard back from about a quarter of the people who reported deaths, we can speculate that the whole sample had sixteen people in this category.

Suppose each of the 6,000 people who took my survey had one relative in this age group (maybe a grandparent). And suppose that each relative got two COVID vaccines (an original and a booster). That means there are 12,000 vaccinations of 80+ year-old relatives in my survey population.

The average 80 year old has a 5% chance of dying per year; the average 90 year old a 20% chance. Let’s average it out and say 10% for the 80+ population. That means a 1/3650 chance per day, a 1/500 chance per week, etc. So by coincidence, we would expect about 2 people in my sample to have stories of an older relative dying within one day of vaccination, and about 10 people to have stories of a relative dying within one week. Among people talking about vaccine-related deaths, they seem to range from “same day” to “within six weeks”. So I think this mostly fits the null hypothesis.

I don’t think the null hypothesis is quite right here, for two reasons. First, as Respondent 1 notes, some people receive the COVID vaccine in the hospital, when they go there for other reasons, which seems like a time of elevated death risk. Second, Respondent 2 notes that some people are so frail that even normal vaccine side effects of the type that everyone agrees exist might kill them. On the other hand, there might be a tendency for people to wait until they’re healthy to get the vaccine, which would counterbalance these effects. Overall I think the null hypothesis is an okay estimate here though.

What about the 37 year old? Yes, he was very obese, but this is still an unusual age to die. Suppose the average respondent has two relatives in this category. Then by a similar calculation, we should expect about 24,000 vaccinations in the population. The average 37 year old has a 1/100,000 chance of dying on any given day. So there’s about a 1/4 chance that we would see an event this extreme in this population (or 1/2 if we interpret “the day after” to mean “not the same day”). But also, since only 1/4 of people answered my email, we should be concerned that there are three other events like this in this sample. This makes it an unlikely, but not extremely unlikely, finding.

III.

I interpret the results of my survey to be consistent with a null hypothesis of “the vaccines don’t increase deaths”, plus or minus some very small effect of “they can kill the extremely frail” or “they can cause a heart attack in susceptible young people 1/10,000th of the time”.

That still leaves the question of why my results are so different from those of Kirsch, Pollfish, and Rasmussen.

Maybe there’s some very big population of people who got the vaccine, then died eventually (where “eventually” could be anything from the same day to years later) of some condition (where “some condition” ranges from things plausibly connected to vaccines like allergic reactions, to things not plausibly connected to vaccines like lightning strikes). Depending on people’s previous assumptions about the risks of the vaccine, they’ll either report these as vaccine-related deaths, or think of them as unrelated coincidences. This would explain why my data found that Trump supporters were 20x more likely than Trump opponents to know a vaccine-related death.

But this can’t be the whole explanation: ACX readers are only a little further left than the general population, and even the most pro-Trump ACXers reported lower death rates than the median Kirsch poll respondent. My guess is that this is a blog about statistics and reasoning, so people here are very cautious about the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy.

I think the best conclusion from this result is just to stop caring about these kinds of polls. Any poll whose outcome can change by more than an order of magnitude based on the respondents’ politics or statistical knowledge isn’t a valid guide to the frequency of real-world events. This should have been our leading hypothesis all along, but the results were weird enough to be worth checking. Now that we’ve checked, we can forget about this methodology and focus on the result of peer-reviewed studies, like we should have done all along.

As always, you can try to replicate my work using the publicly available ACX Survey Results. If you get slightly different answers than I did, it’s because I’m using the full dataset which includes a few people who didn’t want their answers publicly released. If you get very different answers than I did, it’s because I made a mistake, and you should tell me.