Highlights From The Comments On Acemoglu And AI

[original post [here](https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/contra-acemoglu-onoh-god-were-doing)]

Eugene Norman writes:

This…

“People have said climate change could cause mass famine and global instability by 2100. But actually, climate change is contributing to hurricanes and wildfires right now! So obviously those alarmists are wrong and nobody needs to worry about future famine and global instability at all.”

…isn’t a good analogy at all. Because nobody is arguing that climate change now doesn’t lead to increased climate change in the future. They are the same thing but accelerated. However there’s no certainty that narrow AI leads you a super intelligence. In fact it won’t. There’s no becoming self aware in the algorithms.

I’m against this for two reasons.

First, self-awareness is spooky. I honestly have no idea what self-awareness is or what it even potentially could be. I hate having this discussion, because a lot of people who aren’t aware of the difference between the easy and hard problems of consciousness get really worked up about how they can definitely solve the easy problem of consciousness, and if you think about it there’s really no difference between the easy and hard problem, is there? These arguments usually end with me accusing these people of being p-zombies, which tends to make them angry (or at least cause them to manifest facial expressions and behaviors associated with anger).

I suspect self-awareness is either some kind of extremely convincing illusion, some kind of joke God is playing on an otherwise completely materialistic universe, or some computational property which will be really boring and unsatisfying once we figure it out (eg this). What I absolutely don’t expect is that there is some kind of extra thing you have to add to your code in order to make it self-aware - import neshamah.py - which will flip it from “not self-aware” to “self-aware” in some kind of important way.

But also, who cares? Non-self-aware computers can beat humans at Chess, Go, and Starcraft. They can write decent essays and paint good art. Whatever you’re expecting you “need self-awareness” in order to do, I bet non-self-aware computers can do it too. Computers are just going to get better and better at stuff, and at some point probably they’ll be as good as humans at various things, and if you ask them if they’re self-aware they’ll give some answer consistent with their programming, which for all I know is what we do too.

I’m reminded of Dijsktra’s claim that whether a computer can think is like the question of whether a submarine can swim. Sure, say that you’re not worried about submarines because no naval engineer in the world has a plausible path to creating a submarine that can truly swim. Point to the schematics, and prove that there is no “swimming” anywhere in the engine or reactor. You’ll be completely right, and have proven something very interesting about the deep philosophical category of swimming, and the submarine can just nuke you anyway.

—————————————————

Chris Thomas writes:

I think a lot of this stems from the fact that folks believe some pretty fantastical things about algorithms. They think that algorithms are Brainiac or something, when really they’re more like the random street punks that Batman beats up—ultimately acting at the behest of someone or something else. An algorithm is capable of great harm, don’t get me wrong, because humans are behind them and we’re capable of great harm, but they quite literally lack the necessary components to become a general super intelligence.

I think the distinction between “narrow” and “general” AI is a spook. It might be useful terminology, but if you reify it you’re going to end up confused and hopeless.

I guess this is a continuation of the previous point. I think a lot of people believe there’s some boring thing called an “algorithm” which can just do one task, and then some exciting thing called “intelligence” which is made in the image of God and capable of limitless possibility. People see that right now AI is just the algorithm thing, and not the true-intelligence thing, and think - well, it’s probably going to be really hard to do the second thing. Might never happen. At the very least it’ll take some incredible genius to figure out the secret. Probably we shouldn’t start worrying about it until that happens.

I think some of the people saying this are kind of confused about how modern AI works. I’m also confused about how modern AI works, so please excuse any inaccuracies in the following, but basically:

Let’s say you want to make an AI play Go. You design some AI that is very good at learning. Then you make it play Go against itself a zillion times and learn from its mistakes, until it has learned a really good strategy for playing Go.

The AI started out as a learning algorithm, but ended up as a Go-playing algorithm (I’m told it’s more complicated than this, sorry). When people talk about “stupid algorithms” or “narrow algorithms”, I think they’re thinking of Go-playing algorithms. Certainly when we discuss “algorithmic bias” in parole or something, we’re talking about some algorithm that gets used as a strategy for deciding who gets parole. In the extreme case, this might just be a simple linear model or something. Maybe it’s c^2 + 2a + 99999b, where c is the heinousness of the crime on a scale of 1-10, a is the offender’s age, and b is whether they’re black or not. Obviously this algorithm is “stupid” and “narrow”, in the sense that you can’t make it play chess - it’s not even that it would be bad at chess, it’s that asking it to play chess doesn’t even make sense. I think this is part of what people mean when they say “an algorithm is just narrow, so it would have to become self-aware in order to do anything”. Obviously your polynomial for deciding parole isn’t going to become superintelligent one day.

But can the learning algorithm learn to play chess? Yes, extremely well. DeepMind got their Go AI AlphaZero to try learning chess, and it became world champion within a day. Then they asked it to learn a different game called shogi, and it became world champion of that one too. Could AlphaZero learn how to invent new rockets? No, because that’s not the class of problems it knows how to learn about (it’s not a board game where it can play against itself a bunch of times and observe its mistakes). So is the learning algorithm a narrow AI or a general AI? It’s not infinitely narrow - it can learn any board game you throw at it - but it’s not infinitely general either. Certainly it’s more general, smarter, and at least slightly scarier than a polynomial that predicts parole decisions.

Right now a lot of research is going into making things that are slightly more general than AlphaZero. For example, could you get something which, in addition to being able to play any board game, can also play any video game? This turns out to be a really different problem; my understanding is that they’re pretty close but not quite there. What about just games in general? Last week, DeepMind published a paper, Open-Ended Learning Leads To Generally Capable Agents. They created a simulated 3D physical environment, stuck an AI in a simulated body in that environment, and made it go through various obstacle courses and stuff. They found that the knowledge generalized, so that the AI was eventually able to learn to play games they hadn’t taught it, like hide-and-seek and capture-the-flag, coming up with decent strategies on their first attempt based on the general principles it had learned from other things. Where does this place it on the “it’s just an algorithm” vs. “real intelligence” dichotomy?

I think most people expect that learning algorithms will go through a process of becoming more and more generalized. We’ll go from ones that can only learn Go, to ones that can learn any board game, to ones that can learn any board or video game, to ones that can learn skills like writing and art (you are here!), to ones that can learn any game or skill broadly defined, to ones that can learn fields/careers/etc, to ones that can do all those things and also learn how to navigate the world as an agent and pursue larger-term goals. The worry isn’t that one day an equation for making parole decisions becomes superintelligent, it’s that general-purpose learning agents become really good at learning lots of stuff and learn to do things we weren’t expecting or didn’t want.

—————————————————

DYoshida writes:

This isn’t directly related to the article, but it did remind me of a gripe I’ve had bouncing around in my head a bit lately.

I’m skeptical of the risk of near term AGI, so I’ve had several conversations with people of the “true believer” variety, following roughly this skeleton:

Person: <saying things which imply the risk and near-term likelihood of AGI are high, possibly involving phrases of the flavor “of course that won’t matter in 5-10 years blah blah”>

Me: I think this subculture vastly overstates the plausibility and risks of near-term AGI

Them: Well, since the potential downside is very high, even a small probability of us being right means it’s worth study. You want to be a good Bayesian don’t you?

Me (wanting to be a good Bayesian): Ah yes, good point. Carry on then.

Them: resumes talking about their pytorch experiment as if it is a cancer vaccine

To me it feels very Motte-and-Bailey. Having been attacked in the Bailey of high probability occurrence, a swift retreat to the Motte of expected value calculations is made.

Now, I don’t think actions by institutes working on alignment or whatever are necessarily misguided. I’m happy for us to have people looking into deflecting asteroids, aligning basilisks, eradicating sun-eating bacteria, or whatever. It’s more that I find the conversations of some groups I’d otherwise have quite a lot in common with, very off-putting. Maybe it’s hard to motivate yourself to work on low probability high-impact things without convincing yourself that they’re secretly high probability, but I generally find the attitude unpleasant to interact with.

I don’t know how much of this is people being dumb, vs. the AI field having a lot of diverse opinions and it’s hard to remember it’s different people, vs. people thinking about probabilities differently. I think the closest thing to a consensus is Metaculus, which says:

-

There’s a 25% chance of some kind of horrendous global catastrophe this century.

-

If it happens, there’s a 23% chance it has something to do with AI.

-

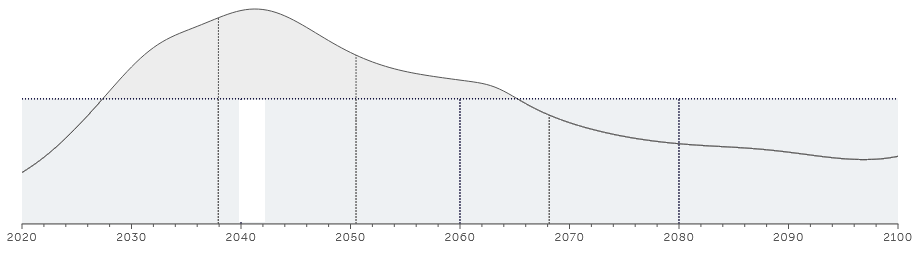

The distribution of when this AI-related catastrophe will occur looks like this:

My personal estimates are more like 75% chance, 25% chance, and a distribution that peaks about 20 years later than this one.

My personal estimates are more like 75% chance, 25% chance, and a distribution that peaks about 20 years later than this one.

I think the Metaculus position is consistent with all of “this probably won’t happen”, “THIS IS SUPER-TERRIFYING”, “this is most likely far away”, and “BUT FOR ALL WE KNOW IT COULD BE TOMORROW!” I realize this is an annoying way for things to be.

—————————————————

CraigMichael writes:

> But all the AI regulation in the world won’t help us unless we humans resist the urge to spread misinformation to maximize clicks.

Was with you up to this point. There are several solutions to this other than willpower (resisting the urge).

The basic idea - change incentives so that while spreading misinformation is possible but substantially less desirable/lucrative than other options for online behaviors.

This isn’t so hard to imagine. Say there’s a lot of incentives to earn money online doing creative or useful things. Like Mechanical Turk, but less route behavior and more performing a service or matching needs.

Like I wish I had a help desk for English questions where the answers were good and not people posturing to look good to other people on the English Stack Exchange, for example. I would pay them per call or per minute or whatever. Totally unexplored market AFAIK because technology hasn’t been developed yet.

Another idea - Give people more options to pay at an article-level for information that’s useful to them or to have related questions answered or something like that without needing a subscription or a bundle. Say there’s some article about anything and I want to contact the author and be like “hey, here’s a related question, I’m willing to offer you X dollars to answer.” The person says “I’ll do it for x+10 dollars.”

One site used to unlock articles to the public after a threshold of Bitcoin have been donated on a PPV basis. It both incentives the author and had a positive externality.

Everyone is so invested in ads that they don’t work on technology and ideas to create new markets.

To paraphrase Jaron Lanier we need to make technology so good it seduces away from destroying ourselves.

Partly I want to complain that obviously I was using the quoted sentence as a rhetorical device. But I guess the whole point of that sentence and its paragraph was to argue against saying false things as a rhetorical device, so - hoist on my own petard, I guess.

I’m less optimistic than Craig is about this solution, because it seems to me that socially virtuous technology will always be less fun/addictive than nonvirtuous technology, simply because the virtuous technology has to hit two targets (virtuous, fun/addictive), the nonvirtuous technology only has to hit one target, and it’s easier to optimize for a target with zero other constraints than with one other constraint. See eg Meditations on Moloch.

—————————————————

Souf asks:

Is there a convincing argument that AGI is possible within any reasonable timeframe (like… 50 years), other than the intuitions of esteemed AI researchers? Do they have any way to back up their estimates (of some tens of percent), and why they shouldn’t be millionths of a percent? It is, as another poster said, an “extraordinary claim.” I’d like to see some extraordinary support of those particular numbers.

If I had to answer this question, I would point to the sorts of work AI Impacts does, where they try to estimate how capable computers were in 1980, 1990, etc, draw a line to represent the speed at which computers are becoming more capable, figure out where humans are at the same metric, and check the time when that line crosses however capable you’ve decided humans are. This is obviously really hard because you have to operationalize some definition of “capable” or “intelligent” or some other word that is hard to operationalize, but when you do it you usually get sometime in the mid-21st century.

You’re going to point out that this argument doesn’t really qualify as “convincing”. I admit it doesn’t meet trial-by-jury standards of evidence. So I guess my real answer would be “it’s the #$@&ing prior”. Like, you certainly don’t have knock-down evidence that it’s impossible, I don’t have a knock-down evidence that it’s certain, so it might happen and it might not. How “might” are we talking? I don’t know, it would seem weird if this quickly-advancing technology being researched by incredibly smart people with billions of dollars in research funding from lots of megacorporations just reached some point and then stopped. Okay, fine, maybe it will keep advancing at the same rate, how fast is that in terms of time-to-AGI? Now we’re back at AI Impacts drawing lines again.

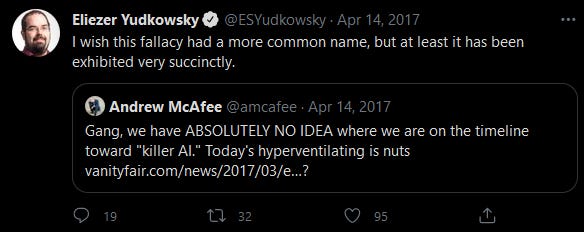

The stupidest possible prior is always 50-50. We would have to be very stupid people to use the stupidest possible prior. But here we are. I wouldn’t want to give a 50-50 chance of us inventing FTL travel by 2100, because FTL travel seems physically impossible. I wouldn’t want to give a 50-50 chance of us inventing slower-than-light-but-still-pretty-good starships by 2100, because, I dunno, space travel isn’t advancing that fast and nobody is really working on it that hard. For AI, I don’t know, I kinda want to say 50-50. If I were going to try to update away from 50-50, I would want to look at AI Impacts style line graphs, expert opinion, and prediction markets. All of those seem to make me update up instead of down, so I don’t think I would go lower than 50-50. But there’s enough Knightian uncertainty to make an entire Round Table here, so who knows? Hardly a “convincing” argument, but I’m just trying to avoid the McAfee Fallacy:

—————————————————

Souf continues:

The argument that we are “in the middle of a period of extremely rapid progress in AI research, when barrier after barrier is being breached” makes it seem like all AI “progress” is on some sort of line that ends in AGI. That feels like sleight-of-hand. Even Scott himself refers to AGI here as a “new class of actor,” so I’m failing to see how current lines of “progress” will indubitably result the emergence of something completely novel and different?

Lots of smart people disagree with me on this one, but I think the path from here to AGI is pretty straight. I mean, it will take thousands of people who are all much smarter than I am to do it, but it’ll happen.

My argument is something like - human brains are remarkably similar to rat brains, only much bigger. They’re still a little similar to insect brains. It looks like if you have a basic functioning brain, and you scale it up, it gets human intelligence.

Existing AIs like AlphaGo or GPT seem to be basically a blob of learning-ability, a plan for pointing the blob at a specific problem, and lots and lots of training data. I think the past five years have shown that this basic model generalizes really well. OpenAI’s programs can now write essays, compose music, and generate pictures, not because they had three parallel amazing teams working on writing/music/art AIs, but because they took a blob of learning ability and figured out how to direct it at writing/music/art, and they were able to get giant digital corpuses of text / music / pictures to train it. DeepMind is finding that it can win lots of games, from Go to StarCraft to obstacle courses in simulated environments, by pointing a blob of learning-ability at the game and making it play against itself a zillion times (ie generate its own training data).

My impression is that human/rat/insect brains are a blob of learning-ability which the rest of the nervous system successfully points at the world, and especially at aspects of the world that the organism needs to pay attention to (eg food sources, sex, etc). This isn’t exactly right, there are a few genetically-encoded programs, but not that many and it’s pretty hard. Right now I think our main advantages over AI systems are something like:

-

our nervous system is pretty good at pointing us at the world and extracting training data from it. If you wanted an AI that learned being-in-the-world skills as well as we do, it would have to have an amazing robot body, and right now robot bodies aren’t that amazing.

-

AIs have to play zillions of games of chess to get good, but humans get good after only a few thousand games. We learn to walk within a year or so, we learn language after only a year or two of listening, etc, and I don’t think AIs could do any of those things so fast right now. That probably means our blob of learning-ability is better than theirs is. This might just be because it’s a bigger blob. We still have way more neuron-equivalents than they do, though they are catching up.

-

The human motivational/attentional system is very confusing, and I don’t know if AIs have an equivalent. It’s possible that something like this shows up naturally if you point a blob of learning-ability at a task that requires motivation/attention - I know DeepMind’s AIs can play games that require task-switching sorts of things, so they must have something like this. But it’s possible that humans have a lot of inbuilt structures that make this easier/more-natural, and without those AIs won’t feel “agentic”. This is the thing I think is likeliest to require real paradigm-shifting advances instead of just steady progress.

I think it’s completely plausible that we just keep building better and better blobs of learning-ability, and coming up with more and more ways to direct the blobs at interesting tasks we care about, and eventually getting AIs that feel “human level”. Or we might get stuck at some point, maybe for reasons relating to motivation/attention. But I do think this way of thinking about things makes me more near-termist than some people. See also Where The Falling Einstein Meets The Rising Mouse.

—————————————————

Lizard Man writes:

Gotta disagree. Working on fixing the long term threat of super intelligent evil AI will not necessarily help you fix today’s problems, but fixing today’s problems will most certainly teach you something about fixing the long term threat, should it exist. I mean, I can’t offer a complete criticism of the work done in AI risk, and I’m not going to sit here and play utilitarian table tennis with you over what extent we should worry about both the worst and least worst case at the same time. What I can do is choose where to put my money and time, and i think i make the reasonable choice not to spend too much time writing or building anything in the world of ‘hypothetical AI’, so to speak.

I can’t disagree with this too much, since it was one of the arguments I made in the original piece - instead of viewing near-term and long-term AI research as natural enemies where you have to put down one to support the other, view them as potentially complementary, where we should work to understand AI better in order to prevent both short-term and long-term risks.

Still, I don’t think this is so true that you can just concentrate on the near-term and not on the long-term at all (I guess a more charitable way to frame this would be to deal with problems as the come up, and deal with the long-term ones in the future after they’ve started happening).

Maybe the strongest argument for just doing near-term stuff now this is that you can’t try to fix a problem until you know its shape and have examples of the problem to poke at and try to fight against. I think there’s some merit in this, but a lot of long-term AI work is trying to come up with situations where toy versions of the next decade’s hard problems will start cropping up today, then poke and prod at them and try to solve them. I would rather poke and prod at the toy problems now than poke and prod later at actually important things which can poke back.

One of the main problems AI researchers are concerned about is (essentially) debugging something that’s fighting back and trying to hide its bugs / stay buggy. Even existing AIs already do this occasionally - Victoria Krakovna’s list of AI specification gaming examples describes an AI that learned to recognize when it was in a testing environment, stayed on its best behavior in the sandbox, and then went back to being buggy once you started trying to use it for real. This isn’t a hypothetical example - it’s something that really happened. But it happened in a lab that was poking and prodding at toy AIs. In that context it’s cute and you get a neat paper out of it. It’s less fun when you’re talking twenty years from now and the AI involved is as smart as you are and handling some sort of weaponry system (or even if it’s making parole decisions!)

There are also the problems for thirty or forty years from now that aren’t even happening in toy models in labs. In these cases, I still think it’s worth figuring out whether there are easy common-sense things we can do today to build the foundations on which we can fight them tomorrow. Kind of like the Y2K bug - people in 1970 (or whenever) couldn’t have predicted the full course of computer development in 2000 - but they could have predicted that only leaving two digits for the year was eventually going to cause a bad time. Instead of having to rewrite every piece of code on a deadline in 1999, they could have thought a bit ahead, changed the way they were doing things then and there, and saved the future a lot of trouble.

I feel bad making these reasonable arguments, because I also think we should do a lot of extremely theoretical work trying to figure out the exact way the far future is going to go and prepare for it, for reasons described in this Eliezer Yudkowsky essay.

—————————————————

People really like metaphors!

From Dionysus:

It’s the year 1400, and you’re living in Constantinople. A military engineer has seen gunpowder weapons get more powerful, more reliable, and more portable over the past two centuries. He gets on a soapboax and announces: “Citizens of Constantinople, danger is upon us! Soon gunpowder weapons will be powerful enough to blow up an entire city! If everyone keeps using them, all the cities in the world will get destroyed, and it’ll be the end of civilization. We need to form a Gunpowder Safety Committee to mitigate the risk of superexplosions.”

We know in hindsight that this engineer’s concerns weren’t entirely wrong. Nuclear weapons do exist, they can blow up entire cities, and a nuclear war could plausibly end civilization. But nevertheless, anything the Gunpowder Safety Committee does is bound to be completely and utterly useless. Uranium had not yet been discovered. Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch wouldn’t be born for another 500 years. Nobody knew what an isotope was, and their conception of atoms was as different from real atoms as nuclear bombs are from handgonnes. Rockets existed, but one that could deliver tons of payload to a target thousands of miles away was purely in the realm of fantasy. Even though the Roman military engineer detected a real trend–the improvement of weapons–and even though he extrapolated with some accuracy to foretell a real existential threat, he couldn’t possibly forecast the timeline or the nature of the threat, and therefore couldn’t possibly do anything useful to inform nuclear policy in the 20th century.

A more reasonable military engineer tells the first engineer to focus on more pragmatic and immediate risks, instead of wasting time worrying about superexplosions. Cannons are already powerful enough to batter down all but the strongest city walls, he points out. In the near future, the Ottomans might have a cannon powerful enough to destroy Constantinople’s walls. How will the Roman Empire survive this?

And Deiseach:

These arguments always read to me like “a big dog with sharp teeth is dangerous, can you imagine how dangerous a fifty-foot dog with three heads and even sharper teeth is going to be???” Friend, I’ll worry about fifty-foot high dogs after you get this normal dog’s teeth out of my backside.

Consider a Stone Age man putting some rocks on top of each other to make a little tower, and then being given a vision of the Burj Dubai. Conceptually they seem similar – both towers, one just a lot taller and narrower – but there is actually no way for the Neolithic Man to build the Burj Dubai, and his imaginative thought that just piling a super-duper number of rocks atop each other would do the trick is ultimately delusional.

No amount of rocks piled up will ever become that slender enormous spire, because rock just doesn’t have the right material properties. Indeed, no substance known to Neolithic Man and freely available on the surface of the Earth does.

Neolithic Man needs to become Iron Age man and invent metallurgy, realize the possibility of creating brand-new substances (pure iron) that cannot be found in nature, and then go on to develop high-strength steels, algebra, and theories of mechanics before he can actually build the Burj Dubai.

There is no path from a pile of rocks to a modern skyscraper, and there are very few lessons you learn from piling rocks on top of each other that apply to building a modern skyscraper, aside from “gravity is a thing” perhaps, and the truly enabling technology (the chemistry of iron ores) appears on first glance utterly unconnected to the issue of building very tall and slender towers.

I have no right to complain here because I am kind of Patient Zero for overly-labored-metaphor use. But a lot of these seem to boil down to “if we compare AI to cases where people would have been wrong to worry, we shouldn’t worry. If we compare it to cases where people would have been right to worry, we should worry.”

A late Byzantine shouldn’t have worried that cutesy fireworks were going to immediately lead to nukes. But instead of worrying that the fireworks would keep him up at night or explode in his face, he should have worried about giant cannons and the urgent need to remodel Constantinople’s defenses accordingly. If near-term AI risks are like worrying about fireworks keeping you awake at night and long-term AI risks like worrying about the Ottomans having cannons, then long-term AI worries are right. But if near-term AI risks are like worrying about the Ottomans having cannons and long-term AI risks are like worrying about nukes, then long-term AI worries are wrong.

Maybe the real lesson here is that we should only worry about the most medium-term of risks? That way we can accuse the people worrying about nearer-term risks than we are of being like Byzantines worried about fireworks, and the people worrying about longer-term risks than we are of being like Byzantines worrying about nukes - whereas we ourselves are clearly most like Byzantines worried about Ottoman cannons.

In conclusion, AI is like a caveman fighting a three-headed dog in Constantinople. The dog is trying to summon a demon, and the demon is going to unleash a genie. The caveman could fight the demon if he had nuclear weapons, but all he has is an antique musket, and also, just yesterday an eminent physicist told him that nuclear fission was “the merest moonshine”. He could escape the genie if he had a Mars rocket, but nobody can solve the rocket alignment problem, and also Mars might already be overpopulated. If only there had been some kind of fire alarm that could have warned him of this!