Highlights From The Comments On "Crazy Like Us"

Some good discussion of PTSD, culminating in a link to the ACOUP blog, which says:

I cannot speak for all pre-modern, ancient or medieval armies. But for the periods where I have read a wide chunk of the primary source material, I’d say there is vanishingly little evidence that people in the ancient Mediterranean or medieval Europe experienced PTSD from combat experience in the way that modern soldiers do.

That is often not the impression that you would get from a quick google search (though it does seem to be the general consensus of the range of ancient military historians I know) and that goes back to arguments ex silentio. A quick google search will turn up any number of articles written by folks who are generally not professional historians declaring that PTSD was an observed phenomenon in the deep past, citing the same small handful of debatable examples. But one thing you learn very rapidly as a historian is that if you go into a large evidence-base lookingfor something,you will find it.

[…]

I think the evidence strongly suggests that ancient combatants did not experience PTSD as we do now. The problem is that the evidence of silence leads us with few tools with which to answer why. One answer might be that it existed and they do not tell us – because it was considered shameful or cowardly, perhaps. Except that they do tell us about other cowardly or shameful things. And the loss and damage of war – death, captivity, refugees, wounds, the lot of it – are prominent motifs in Greek, Roman and European Medieval literature. War is not uniformly white-washed in these texts – not every medieval writer is Bertran. We can’t rule out some lacuna in the tradition, but given just how many wails and moans of grief and loss there are in the corpus it seems profoundly unlikely. I think we have to assume that it isn’t in the sources because they did not experience it or at least did not recognize the experience of it.

The more interesting potential question is why. Considering all of the competing theories for that, I think, would take its own collections post. But for my part,I tend to think the difference lies in part on the moral weight placed on warfare – it was viewed not generally a necessary evil in these societies, but a positive good – which may have meant there was less sense that what had taken place was trauma at all. If that is the case, the emergence of PTSD would speak to improvementin our society: we have become more averse to violence and do it less, and as a consequence, feel it more. If you will permit me, we have more wounded warriors because we have fewer dead ones, on account of having fewer wars in general.

And adds in a different post:

But moreover – and we’ve actually already touched on this when discussing fear and courage – mental wounds also seem to vary somewhat from one modern war to the next. As I noted, the hyper-vigilance that is so often a symptom of combat trauma in the veterans of contemporary wars seems vanishingly rare in the ‘shell shock’ of WWI veterans, who are more often described as lethargic, listless and undirected (symptoms that also show up in WWII for soldiers who had been under combat stress for long periods). The issue has been brought up, so I do want to note that I am, by the by, unconvinced by the suggestion that these WWI-era mental wounds were purely or principally the product of concussions from heavy artillery or the like.

But it should not surprise us that just as different kinds of combat and different kinds of weapons inflict different sorts of physical wounds, so too they inflict different sorts of mental wounds. The soldier who doesn’t know when the next enemy might appear in a crowd of civilians is put under a very different strain than the soldier who is subjected to a week-long artillery barrage while hiding underground; both of them are subjected to a very different strain from the man asked to charge over a field with a spear. I have by no means exhaustively read the literature on PTSD either from the historical or psychological angles (though I have tried to read a lot of it), but I sometimes wonder if experts researching PTSD under-appreciate the degree to which they are dealing with a moving target; descriptions of combat stress disorders in early wars are too often, I think, treated as misunderstandings when they may simply be recording different symptoms from different trauma caused by different stress (though of course it is also true that our understanding of PTSD and related mental combat trauma has improved tremendously).

This makes sense, but then it’s strange that the PTSD symptoms associated with details of modern combat (ie a “soldier who doesn’t know when the next enemy might appear in a crowd of civilians”) so closely resemble the symptoms modern people get after natural disasters, sexual violence, etc.

Or maybe I’m over-generalizing and they don’t? Part of the idea behind the c-PTSD diagnosis is that the kind of PTSD you get from situations more like child abuse is different from the kind you get from situations more like combat. I think it’s still traditional to group combat, natural disasters, and short-term sexual violence together as normal non-c PTSD, but maybe people who know more about this find distinct symptoms there too.

Loweren writes:

Living in Russia, I can say that ADHD (translated as СДВГ) is less recognized by the psychiatry community here because of its unclear aetiology. Doctors usually refuse to treat the patients in the absence of dangerous symptoms, and state the diagnosis as “organic nervous system disorder”, “psychoorganic syndrome” or indeed “neurasthenia”. Adderall and Ritalin are illegal drugs here. Patients usually get prescribed nootropics (glycine, racetams) and adrenaline reuptake inhibitors (atomoxetine).

At the same time there are some articles in popular online magazines telling stories about children and adults struggling with ADHD in Russia. Some people order illegal drugs from nearby countries. Researchers also are aware of it. At the same time, I see some articles talking about US problems with over-medicalization of ADHD with dangerous narcotics driven by profit-seeking pharma companies.

So if you ever wondered what would happen to ADHD people if stimulants weren’t legal, Russia seems like a good test case.

This comment took me aback, because it made me realize I think of ADHD totally differently than any of the disorders in the book, which kind of demands an explanation.

I would be surprised if ADHD was especially culture-bound. Partly this is because it’s much more genetic than most other conditions. But partly it’s because it’s just a really basic deficit. Some people aren’t very smart. Other people aren’t very coordinated. And still other people aren’t very good at concentration / executive function (see my past discussion of this here). There’s no reason why everyone should have the same level of concentration ability, so sure, some people have extremely bad concentration ability (just as some people are really dumb, or really clumsy), and we call that ADHD. This seems much less mysterious than “sometimes people can’t stop dieting and starve themselves to death”.

Different cultures can vary in terms of how much you need to concentrate, how much accommodation they give to people who can’t concentrate very well, whether they medicalize the condition of not being able to concentrate, where they put the diagnosis threshold and what drugs patients are allowed to take - but the overall “not being able to concentrate” feels too close to the hardware level to be culture-bound in any meaningful way.

Banjaloupe solves my mystery about the culture distribution of expressed emotion:

This question interested me as well so I did a quick search for the first review I could find– so caveat that this article is the first time I’d heard of “expressed emotion” and I’m not an expert in the topic.

This focuses more on the association between households with high expressed emotion, and relapse of schizophrenia, but also gives some numbers attributed to Leff & Vaughan 1985 which at first glance do line up with the ones for American and British households from the book (the linked article gives the low-EE %, the quote from the book above is the high-EE %, and they add up to 100%). Despite having a university library access I couldn’t find the Leff & Vaughan paper quickly, though– others might have more success.

Also, I think the definition of “expressed emotion” in the article I linked above helps explain the discrepancy that Scott noted above, that the understood knowledge is that white Americans prefer/demand social environments without big displays of emotion. From what I can tell, “expressed emotion” really is just “expressed emotion (from a schizophrenia patient’s household towards a schizophrenic person)”. It’s a pretty limited definition that’s about the ways that people around a schizophrenic person at home, respond to that person. So, it makes a lot of sense that a culture’s “way of interacting with schizophrenic people at home” could be very different from their “way of interacting with neurotypical people outside of home”.

This is interesting, but I wonder why a culture even has a culture-wide “way of interacting with schizophrenic people at home” separate from their usual interaction patterns. I wouldn’t expect there to be enough people witnessing each other’s interactions with schizophrenic family members for this to spread across a culture. Maybe this is downstream of biological views of mental illness or something?

Coagulopath writes:

I know a woman who was sexually interfered with as a child. It didn’t affect her when it happened. She was old enough to remember it, but the memories weren’t painful. It was just a weird person doing stuff. She certainly didn’t feel like she’d been victimized.

Only later, when surrounded by friends who talked about how awful CSA is and how it ruins your life forever (etc, etc), did trauma from the event hit her.

This might not be a common experience, but it was unsettling to hear her describe that. She felt a degree of bitterness toward her friends: almost as though they’d caused her to become a victim, not her attacker.

Himaldr adds:

I have heard similar from someone I know, as well — that it didn’t seem shameful and horrifying until everyone kept saying how ashamed and horrified she must be. A common thread here might be that in both of these cases, it doesn’t appear to have been violent or forceful - I’d wager that in the more awful cases, other people’s reactions aren’t needed to make it a terrible memory.

Other commenters bring up related arguments - doctors sometimes examine children’s genitals in ways that aren’t obviously different from what goes on in some child sex abuse cases; some tribes have rituals where adults do weird things to children’s genitals - in all these cases, because it’s socially accepted and people aren’t “supposed to” feel traumatized, they usually don’t.

I have a vivid memory of reading a study that basically argued this - victims of child sexual abuse don’t think or care about it much until people tell them that it’s taboo and traumatic, and which point they are duly traumatized - but I can’t find it now. A commenter suggested Rind et al, but this just seems to be a generic “sometimes people aren’t traumatized by child abuse” study, whereas I remember one that clearly made the connection to being traumatized after you’re informed it’s taboo. Does anyone know what I’m thinking of?

CB:

Something else about the book: Watters talks about exporting western psychiatry being equivalent to handing out smallpox blankets. But then he reveals that he’s married to a psychiatrist. He’s, uh, maybe working through some stuff here?

To which Ivan Fyodorovich answers:

Watters has an analogy in the book that imagine if after 9/11, a whole bunch of people from Mozambique flew in and told survivors that they needed to learn rituals for disconnecting their psychic bonds with the spirits of dead relatives. His point was that we would find it weird and insulting, but I think he was also trying to point out that even if these rituals helped Mozambiqueans find peace, outside a larger belief structure they are useless. He also tells the story of a psychiatrist who learns all sorts of stuff about handling psychotic family members in Zanzibar. Then her own husband comes down with psychosis and none of the Zanzibar stuff works. They try religion for example, but you can’t just use religion when you need it, it has to be ingrained in your life and beliefs.

Point I’m trying to make, the book could be read as either “American psychiatry sucks” or “American psychiatry works within the context of American belief systems but can’t just be copied and pasted to other cultures, the same way you can’t just start doing Mozambique spirit rituals tomorrow and expect much from them.” I suspect Watters believes some of both.

One weird but technically-consistent take might be “Western psychiatry is just the equivalent of primitive tribes banging drums to scare off demons - but the drum rituals works great for primitive tribe, Western psychiatry works great for Westerners, and everyone should just stick to what they’re doing.”

A counterargument might be that Western drugs have a lot of side effects - but I suppose that’s no argument against therapy and things like that.

A second counterargument might be that if Western psychiatry only works because we think it does, we would probably want to know that, and then once we figure it out, it would stop working.

Alephwyr (and many, many other commenters) write:

I wonder about the psychology of gender identity in relation to this. It’s been very strange watching transmedicalist narratives be completely obliterated by weird continental perspectives that seem to allow and encourage a distinct gender identity for every possible permutation of quale. Gender identity disorder has increasingly become a cultural phenomenon believed to be on a continuum rather than a discrete alleged biological category. In that way it is somewhat opposite to trends described here, yet the increase is still occurring. It seems like you can track the taint of medicalization in through at least two directions I guess. The reference point would be cultures with strong non binary or non static gender norms perhaps.

I didn’t bring up trans issues because I think they’re a better match for another post I hope to write about related issues in the future, but I agree it sounds like an interesting match for something like this - a psychiatric condition which seems to exists at vanishingly low levels until people work to “raise awareness” of it, after which it becomes very common.

A responsible treatment of this would have to discuss the history of traditional societies around the world that have something vaguely similar to our concept of transgender (like “third gender” roles in certain tribes), then move on to transvestism in the 1980s, and come up with some position on how these relate to modern transgender. One interpretation might be that there is some biological substrate for gender nonconformity (eg some evolved part of the brain that is supposed to tell you what gender you are can misfire in some way), and then the way that people feeling vague anxiety about their gender deal with it varies based on the local cultural milieu.

A second, totally different line of research/commentary would have to decide whether urging people to focus on it makes it stronger (eg in a traditional society, Alice would be a cis woman who occasionally has the weird feeling that she’s not really female but dismisses this as obviously ridiculous and never thinks about it again, but in our society where her gender and the possibility that it might be wrong is constantly called to her attention and reified, this turns into full-blown gender dysphoria). I am sympathetic to this based on an experience I had, where I was pretty bad at tolerating noise, but kind of within the normal human spectrum and never thought much of it, and then I lived with a noisy roommate who characterized my distaste for noise as freakish and psychiatric-level, and after that, every time I heard a noise I started panicking and questioning whether I was going to have some sort of freakish and psychiatric-level reaction to it, and this became so unpleasant that now I do have a freakish and psychiatric-level noise intolerance - or at least this is how I remember it. Also some gender experiences other people have described to me that I don’t have their permission to share with you.

Robert McIntyre quotes a paragraph of mine where I say that “the null hypothesis is that there are lots of people suffering in silence until people raise awareness of and destigmatize a mental illness, after which they break their silence, admit they have a problem, and seek treatment”, then adds:

I think that the null hypothesis is almost certainly right in this an in many other cases, and the strongest evidence I have for this is childhood sexual abuse. I’m almost certain that we’ve always been brutally sexually abusing children as a society for as long as humans have been around. Even if that’s not the case, I KNOW that the boomers in America were often sexually abused as children. Both my parents were raped / abused as kids. My grandmother was raped. About 75% of my aunts / uncles were abused / raped. Around 20% of the boomer friends I have that I’ve had deep conversations with have shared stories with me of them being raped / sexually abused as children. I think the actual real prevalence based on my own experience is probably somewhere between 20%-50%. Go talk to some of your boomer friends that actually trust you and learn how common it was!

And yet, in 1960s there was total, absolute denial in American society that childhood sexual abuse even existed. From The Body Keeps the score:

(Dr. Van Der Kolk): “In my new job I was confronted on an almost daily basis with issues I thought I had left behind at the VA. My experience with combat veterans had so sensitized me to the impact of trauma that I now listened with a very different ear when depressed and anxious patients told me stories of molestation and family violence. I was particularly struck by how many female patients spoke of being sexually abused as children. This was puzzling, as the standard textbook of psychiatry at the time stated that incest was extremely rare in the United States, occurring about once in every million women. Given that there were then only about one hundred million women living in the United States, I wondered how forty seven, almost half of them, had found their way to my office in the basement of the hospital.

Furthermore, the textbook said, “There is little agreement about the role of father-daughter incest as a source of serious subsequent psychopathology.” My patients with incest histories were hardly free of “subsequent psychopathology”—they were profoundly depressed, confused, and often engaged in bizarrely self-harmful behaviors, such as cutting themselves with razor blades. The textbook went on to practically endorse incest, explaining that “such incestuous activity diminishes the subject’s chance of psychosis and allows for a better adjustment to the external world.” In fact, as it turned out, incest had devastating effects on women’s well-being.

As Roland Summit wrote in his classic study The Child Sexual Abuse Accommodation Syndrome: “Initiation, intimidation, stigmatization, isolation, helplessness and self-blame depend on a terrifying reality of child sexual abuse. Any attempts by the child to divulge the secret will be countered by an adult conspiracy of silence and disbelief. ‘Don’t worry about things like that; that could never happen in our family.’ ‘How could you ever think of such a terrible thing?’ ‘Don’t let me ever hear you say anything like that again!’ The average child never asks and never tells.

After forty years of doing this work I still regularly hear myself saying, “That’s unbelievable,” when patients tell me about their childhoods. They often are as incredulous as I am—how could parents inflict such torture and terror on their own child? Part of them continues to insist that they must have made the experience up or that they are exaggerating. All of them are ashamed about what happened to them, and they blame themselves—on some level they firmly believe that these terrible things were done to them because they are terrible people.

What conclusion can we draw from this? I think the most reasonable one is that psychiatrists (and doctors in general) are EXTREMELY bad at their jobs. They see what they want to see, they are controlled by the prevailing narratives they’ve been taught, and they don’t really listen to their patients. It’s clearly true that if you’re told during medical school to ignore really significant problems that essentially all doctors will happily ignore these problems for their whole career. And society has awesome mechanisms in place that can brutally suppress any stories of abuse or problems from getting out into wider awareness. These mechanisms (which also exist in other cultures) are so strong that I think they mostly invalidate whatever Crazy like Us is trying to say. The author of Crazy like Us would have to have done MUCH more rigorous work to overcome the fact that there are powerful conspiracies in every society that work to obscure and hide all kinds of mental problems / abuse / internal feelings. It doesn’t look to me like he’s done that work.

This is a great point and a great example; see my review of The Body Keeps The Score for more.

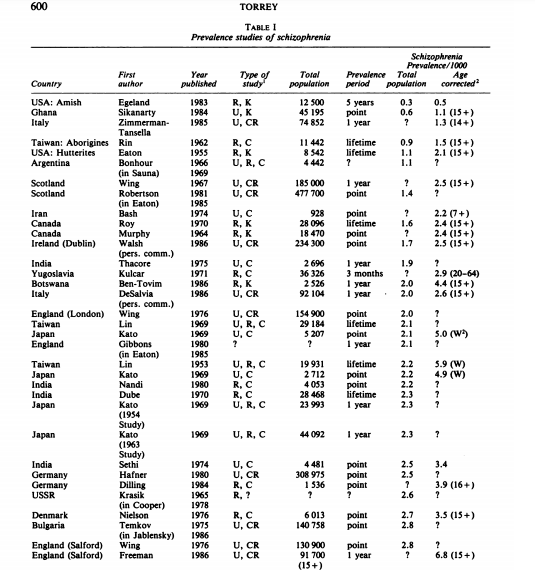

@crimkadid on Twitter is unhappy with my repeating the psychiatric platitude that schizophrenia has uniform prevalence everywhere. They point to a 1987 meta-analysis which finds large cross-cultural differences:

This is still controversial and it’s hard to figure it out correctly, but after double-checking, a lot of the educated opinion has switched over to crimkadid’s view (see eg McGrath 2008), which calls the uniformity hypothesis a “dogma”. Sorry for getting this wrong. Crimkadid is also responsible for this long twitter thread on variance in schizophrenia, which is poorly-supported, bizarre, and racist, but otherwise excellent - you can find many other interesting speculations at the same account.

Artischoke writes:

One theme running through this book review (that is particularly visible in the discussion of PTSD) is the Western trend to diagnose more and more things as psychiatric illnesses. I think that in turn is mainly caused by a Western philosophy of life where people are individuals entitled to happiness and success, but if they aren’t happily achieving success something must be wrong with them. I.e. I am problematic if I don’t live up to an unrealistic standard for human beings that is expressed through all kinds of channels including the work-place, the treatment of the unemployed, or the lives of other people we see on TV or social media. Hence there is a large demand to produce diagnoses to address the perceived abundance of personal defects.

I agree with the book that in general the West is very successful in exporting this aspect of its culture overseas. The most harmful aspect of which might be exporting the idea of “There is a problem with me, I am deficient”. Once this idea has been successfully implanted somewhere, this will naturally also create a robust demand for Western styles of psychotherapy, apparently justifying the mushrooming of psychiatric diagnoses.

This was stressed more in the original book and mostly didn’t make it into my review.

A common position in some premodern or developing societies is “life is obviously terrible, but whatever, suicide is a sin, so guess we have to deal with it”. Watters tried to play this off as a cultural difference, but life in a lot of places is pretty terrible, in ways that are hard to cover up.

One of the book’s case studies was on the mother of a kid with very severe, disabling mental illness. This really limited the mother’s life - she couldn’t really do her own things, she could never leave her kid alone, she was at risk of violence - and an anthropologist tried to gently probe whether she might feel depressed or traumatized by some of this. But apparently it barely registered next to all the other crappy things about being a woman in a patriarchal extremely poor society. A modern Westerner in this position might be sad because it meant she could never achieve her dream of traveling all over the world, or taking night classes to become an artist, or something like that. But this woman was basically expecting to work hard living a hand-to-mouth existence until she died anyway, so the fact that she wasn’t self-actualizing wasn’t such a problem.

It also reminds me of my article on why suicides dropped during the worst part of the COVID pandemic, where one of the going theories was “if everyone is miserable, and you have no right to expect anything other than misery, then your own misery is more tolerable”.

Dues asks:

Weird question: Where does the discussion on animal depression fit in Ethan Waters view?

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/16/science/depressed-fish.html

(The fish depression fits less well in my view because they seem to be experiencing withdrawal rather than depression?

I should clarify that the book mostly doesn’t say there is no mental illness without culture (or without a belief in mental illness). It says that the way mental illness presents is shaped by culture, and conforms to the culture’s norms. So everyone will get depression, but it will have different symptoms, and people will think of it differently.

The part where this becomes confusing is I guess where you draw the boundaries of mental illness. If you think of (anorexia and conversion disorder) as two “symptoms” of some underlying nameless illness, then maybe some places will have conversion disorder (but no anorexia) and other places will have anorexia (but no conversion disorder), and then it will look like Westerners “brought” anorexia to a place that was previously anorexia-free. The only problem with this way of looking at things is that if true, you would expect some other illness (in this case, conversion disorder) to decrease at the same time anorexia increased, and I don’t know of any research on whether this happened or not.

Also, I don’t know if things like the giant increase in neurasthenia in Japan after people started glorifying it is like this, or whether it was just a giant increase in neurasthenia, with no benefits or compensations.

Also from Ivan Fyodorovich:

I found the trauma section of the book very compelling, in part because it squares with my impression of the United States as a society that is convinced it understands trauma better than any previous society but seems to achieve uniquely poor outcomes. It would be like a land that was convinced it had the best vaccine for polio but you look around and every fourth person is in an iron lung.

I see this most clearly with recent war veterans. 45% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans file for disability, a large fraction psychological: https://www.bostonglobe.com/news/nation/2012/05/27/almost-half-new-veterans-seek-disability-benefits/sYQAAY00ddXBRoqfsKMheJ/story.html

Perhaps some are outright malingerers, but clearly for a large number (including a friend of mine) this is real. They really are suffering from a set of symptoms consistent with PTSD. And yet, the vast majority of WWI veterans, Holocaust survivors, everyone who lived through WWII in Western Russia etc., a large fraction of people in the Middle Ages etc. experienced as bad or worse stuff and the vast majority could function as adults. It’s hard to escape the conclusion that we’ve created an expectation of disabling trauma and people fulfill it. Crazy Like Us quotes an American soldier who said that he felt like an actor given a script. Here’s PTSD, this is what you do next.

I don’t think we can create the anti-psychiatry society like in Scott’s post, but we can send a message that left to their own devices the vast majority of people who experience terrible things will recover, and they shouldn’t expect PTSD.

I think about the first paragraph here a lot.