Highlights From The Comments On Hanson And Health Care

Most recent post here.

Table Of Contents:

1: Comments From Robin

2: Comments About/From Goldin et al

3: Comments From The Rest Of You Yokels

1: Comments From Robin

In response to my most recent post, Robin quoted more of his CATO Unbound article, then wrote:

While I feel this quote is pretty clear, I also agree with Scott that he isn’t the only person to misunderstand me. So let me try again.

Every study on the marginal effect of medicine has some way it operationalizes “marginal medicine” for the purpose of that study. In geographic variation studies, it is the medicine done in places that spend more on medicine, but not in places that spend less. For studies that compare large to small hospitals, it is the treatments done in large but not small hospitals. For experiments that vary the price of medicine or insurance, it is the medicine chosen by subjects who faced lower prices, but not chosen by those who faced higher prices. I remember at some point also suggesting using treatments with a lower Cochrane Review rating.

My key point was and is that each of these operationalized definitions of “marginal medicine” offers a concrete way to avoid marginal medicine. As an individual considering various possible treatments, here are five ways:

Ask about a treatment’s Cochrane Review rating,

Ask if a treatment is done in low spending geographic regions,

Ask if treatments are done in small hospitals,

Ask your doctor how strongly they recommend a particular treatment; decline if recommendation is weak. (I’ve done this.)

Ask yourself and associates if you would be willing to pay for them out of your own pocket, if insurance did not cover them.

Maybe even better to ask several of these questions, and average their answers.

As a wonk considering various possible policies, you can also consider regulating or subsidizing/taxing based on these indicators. Or consider policies that make more patients face higher personal prices for treatment. When I said “most any way to implement such a cut” I had in mind these sort of options; most any should help. Though my favorite option is still creating agents who face strong direct incentives.

Re Scott’s offered trilemma, I pick #3, though the consensus med position doesn’t identify enough marginal med to cut med in half, and I don’t claim non-marginal med works “well”. “Monkey trap” is not letting go of marginal med, as some of it must help.

I basically agree with this, and apologize to Robin for being suspicious of his position. I think this is a pretty reasonable position, not too far away from mine (although I still disagree on the insurance studies).

2: Comments About/From Goldin Et Al

Remember, this was the study where the IRS sent out reminders for certain taxpayers to get health insurance, those taxpayers did get more health insurance, and this was found to decrease mortality rates vs. control taxpayers. I cited this as evidence that insurance could be helpful; Robin was more skeptical and listed some concerns here. Dr. Jacob Goldin, a co-author of al study, kindly sent me an email explaining his work further:

Dear Scott (and Robin, cc’ed),

A friend referred me to your discussion about the effect of health insurance on health – thanks for discussing my paper on taxpayer outreach with Lurie and McCubbin! I looked at the response by Hanson to your post and wanted to flag some things he wrote about our paper that I think are off base.

1: We had a principled reason for focusing on 45-64 year-olds to maximize statistical power to detect an effect. This balances the fact that on the one hand you want a larger age range to have a big sample, but on the other hand mortality is even rarer among younger individuals and our experiment caused fewer younger individuals to buy health insurance. The details of our analysis to choose this age range are in footnote 24 of the paper. We would expect smaller and less precise effects as you include more younger adults in the sample, so it is not surprising that our finding gets less statistically precise as you look at those other age ranges.

2: Projecting the results to longer durations of insurance. There is extensive discussion of this in the paper so I won’t rehash it here, but the main point is that we wouldn’t expect the effect of the first few months of insurance on health to be the same as the effect of subsequent months of insurance on health. You can’t just project outward like he does and expect to get sensible results.

3: Comparing OLS and IV results. I really didn’t understand what point Hanson was trying to make here. In this context, OLS means comparing mortality among people who enroll in more months of health insurance to people who enroll in less. Differences in health insurance enrollment are non-random though, so we don’t put much weight on the OLS estimate. Why would we be concerned that our 95% confidence intervals for the IV and OLS estimates don’t overlap? Note also that the OLS standard errors are much smaller not because of a type-o in the table but because they are estimated from a different source of variation.

4: Effect size. Our view (as we wrote in the paper) is that the results of the experiment provide strong evidence on the sign of the effect of health insurance on mortality, but weak evidence as to the magnitude of that effect. The 95% confidence interval for our IV estimates encompasses both very large effects of health insurance on health as well as much smaller effects. Based on my prior, I think the lower portion of the 95% confidence interval is most likely, but there is undeniably uncertainty here.

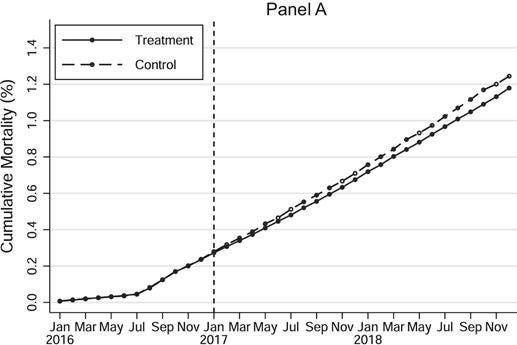

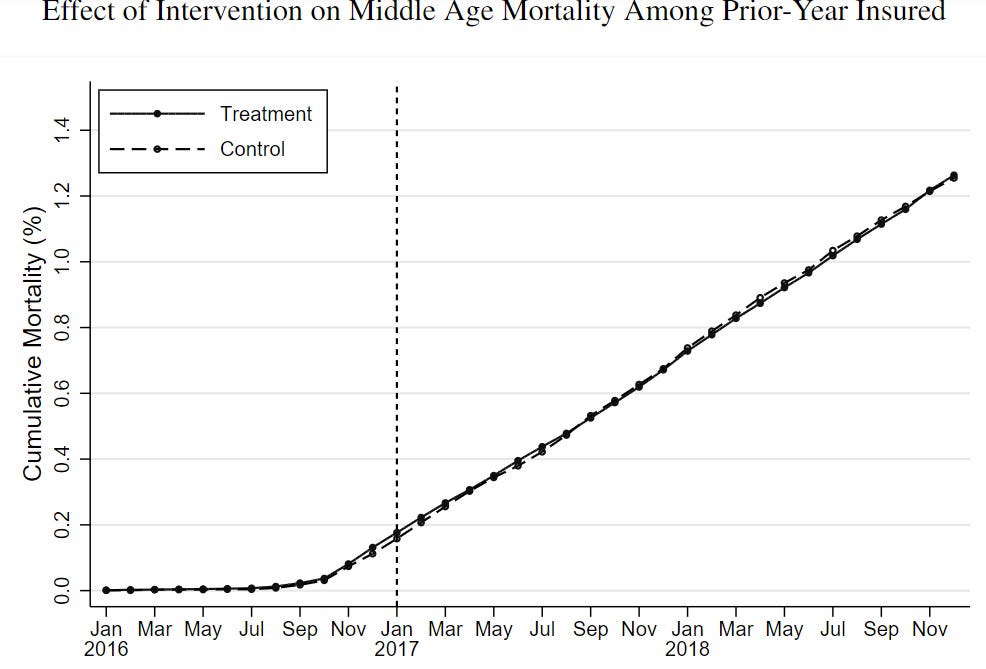

5: Finally, in my view, some of the most convincing evidence in the paper that health insurance affects health comes not from simply looking at the main IV estimate and p-value, but rather from other aspects of the results. As Figure III (copied below) shows, there is no difference in mortality rates between the treatment and control groups in the pre-period, and the gap between the groups gets bigger over time. Conversely, when we compare mortality for two groups of taxpayers who received the letters but didn’t purchase much new insurance (because they were already insured by the time of the intervention), we don’t see a difference in mortality (Figure A.VIII in the appendix, also copied below). You wouldn’t expect to see these patterns if the results were simply noise.

Last point, which is not about my paper, but I’ll weigh in to say that it is not defensible to dismiss the body of very high quality quasi-experimental research finding an effect of health insurance on mortality, such as the Miller et al. paper that studies Medicaid expansion or the Goodman-Bacon paper on childhood Medicaid coverage. Those are a solid part of our evidence base on this question. These very authors have put out other prominent papers finding null results on other policies– you can’t simply point to publication bias and dismiss this entire body of research!

Thanks again for engaging.

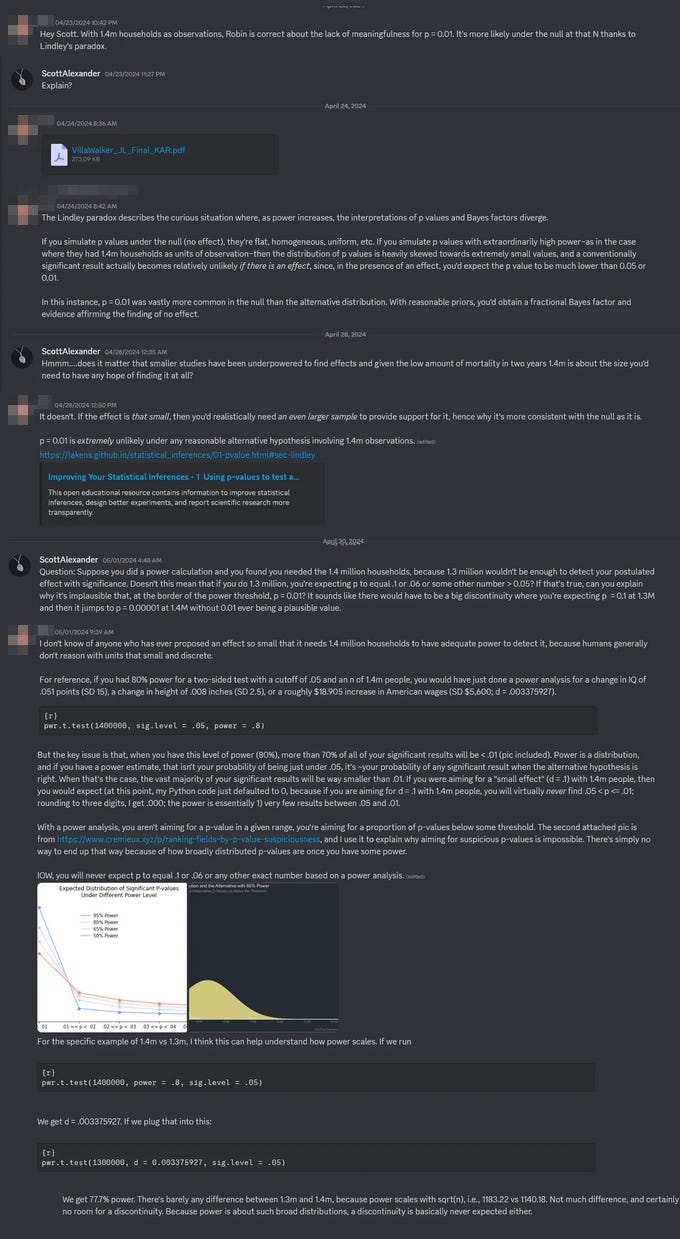

Cremieux brought up a concern about Lindley’s Paradox:

IIUC, this is something like - if the effect was real, at this high a power, there are many p-values we might get - anything from 0.001 to 0.00001 and so on. So it’s actually quite a coincidence that we only get 0.01, pretty close to our significance bar. And in fact the level of coincidence required to produce this under the null (1%) is less unlikely than the level of coincidence required to produce such a precisely-calibrated real effect.

I asked Dr. Goldin about this argument. He answered:

I don’t think it’s a good general rule to say that just because you have a very large sample and a moderate p-value, you shouldn’t reject the null hypothesis. On Lindley’s Paradox, I’m not an expert but my understanding is that there’s not really a paradox, it’s just that a bayesian and frequentist approach are asking different questions, and whether you prefer the null hypothesis vs the alternative hypothesis can depend on your prior. More generally, even with millions of observations, it is very difficult to find statistically precise differences in mortality because mortality is such a rare event, and because the letters we sent didn’t convince everyone in our treatment group to buy health insurance, and some of the people in the control group who did not receive a letter still chose to buy health insurance on their own. So it’s not like one should automatically assume that any large sample size would generate a miniscule p-value if the null hypothesis was incorrect.

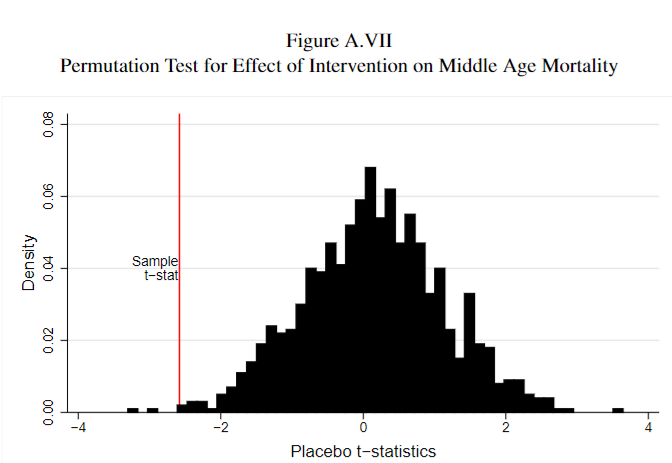

Here’s one last way to understand the statistical significance of the results, which might be more intuitive. Suppose you were to take the individuals in our treatment and control groups and randomly re-shuffle them into (fake) treatment and control groups, and compare the difference in the mortality rates between the fake groups. You wouldn’t expect to find an effect, but there might some differences just due to random noise. In Appendix Figure A.VII (below) we do this 1000 times, and compare the difference between the real treatment and control groups (our estimated effect from the study) to the distribution of the differences between these fake-groups. This tells us whether the difference between the treatment and control groups that we observe in the study (shown by the red line) is likely due to chance – the figure below suggests that the answer is no, because it is more extreme than almost all of the fake comparisons.

I have to admit I’m out of my statistical depth here, but this looks convincing.

Dr. Goldin also brought up one “new, seemingly very credible study showing beneficial health effects from insurance-induced medicine”, The Health Costs Of Cost Sharing (Twitter summary here), abstract:

What happens when patients suddenly stop their medications? We study the health consequences of drug interruptions caused by large, abrupt, and arbitrary changes in price. Medicare’s prescription drug benefit as-if-randomly assigns 65-year-olds a drug budget as a function of their birth month, beyond which out-of-pocket costs suddenly increase. Those facing smaller budgets consume fewer drugs and die more: mortality increases 0.0164 percentage points per month (13.9%) for each 100 per month budget decrease (24.4%). This estimate is robust to a range of falsification checks, and lies in the 97.8th percentile of 544 placebo estimates from similar populations that lack the same idiosyncratic budget policy.

Several facts help make sense of this large effect. First, patients stop taking drugs that are both ‘high-value,’ and suspected to cause life-threatening withdrawal syndromes when stopped. Second, using machine learning, we identify patients at the highest risk of drug-preventable adverse events. Contrary to the predictions of standard economic models, high-risk patients (e.g., those most likely to have a heart attack) cut back more than low-risk patients on exactly those drugs that would benefit them the most (e.g., statins). Finally, patients appear unaware of these risks. In a survey of 65-year-olds, only one-third believe that stopping their drugs for up to a month could have any serious consequences. We conclude that, far from curbing waste, cost-sharing is itself highly inefficient, resulting in missed opportunities to buy health at very low cost ($11,321 per life-year).

I bet I can already predict Robin’s response (“establishing that drug withdrawal is bad is a weaker result than proving that starting drugs is good”), but I appreciate this result, especially the finding that patients aren’t actually any good at triaging important vs. unimportant medicine.

3: Comments From The Rest Of You Yokels

Nathan El writes:

Agreed with this, and I particularly like seeing the improvement in mortality for specific conditions over time like this, it strikes me as a really strong argument for the effectiveness of medicine.

What I do think remains a valid sort-of anti-medicine point is that treatment is vastly less cost-effective than prevention, I recall hearing it being about 50 times less so, and so clearly vast savings could be made through government disease-prevention programs such as dissuasion campaigns against and fees on the externalities of risk factors for disease and especially the broad category of “ingested substances” whether food or recreational drugs and even air pollution; the feeing of externalities (“pigovian taxation”) is of course the least econonomically burdensome and indeed in theory if we could properly calculate the value of the externalities it would be economically optimal, since it doesn’t require making any government expenditure and to the contrary actually constitutes a source of income for the government and can substitute for an equal amount of economically harmful taxation, so that’s what seems to me the most obvious major policy to help reduce healthcare costs, though frustratingly it’s foolishly opposed by many and ironically generally the most so by the “taxation is theft” crowd.

Robin’s argument is strongest against prevention, least strong against treatment. There probably aren’t enough cancer patients in the RAND or Oregon studies to say anything about the effect of cancer treatment. But there are plenty of hypertensives, diabetics, smokers, etc. This is why most of the effects we’re debating are secondary endpoints like blood pressure, blood sugar, etc. So while you might or might not be right about prevention being better than cure, it’s not a response to Robin in particular.

Also, I don’t think it’s fair to call most of these “externalities” - you taking marijuana isn’t an externality, it’s you inflicting both the costs and benefits of marijuana on yourself. While I suppose it’s an externality if the government helps fund your marijuana-related-disease health care, I get nervous about this argument, because it implies that if the government helps you in any way then they ought to have power over you. All the government has to do is offer to pay for free STI treatment, and then if you have sex too much it’s an “externality” and you’re “robbing the government” so the government should be allowed to step in and stop you.

Kristianwrites:

A lot of money in medicine is spent doing stuff “just in case” (like unnecessary tests, MRI’s, check ups) as well as making the experience more pleasant for the patient. You could design a maximally cheap health care system from the top down where patients can’t choose their physician, can’t see a specialist without fulfilling specific guidelines, don’t get access to any examinations that aren’t evidence based, where there are long waiting periods for everything that isn’t urgent, – and this would save a lot of money probably without statistical detriment to outcomes. Patients would hate it though. (This is what public health care is like in some countries.) A lot of people with enough money or private insurance would still spend a lot of money to get more “luxurious” care (like going to a specialist right away or getting an MRI even when there is no strict medical need.) The point is that only part of the money in medicine goes to medical outcomes, per se.

This is an important point; even if much of medicine is wasteful, it doesn’t imply that any given treatment doesn’t work.

One big area of waste is over-testing. It’s kind of philosophical exactly how much testing we should do - it depends how you balance money, time, and patient inconvenience vs. very small chances of making a positive health difference - but most people think we’ve gone too far, and the economic incentives probably reinforce that. Regardless of what you think of the philosophy here, this throws off insurance experiments. The insurance experiment might find that the higher-insurance group gets tested more (meaning more doctors visits and higher costs, which show up as negatives) and the benefit is 1/1000 extra cancer cases caught early (which doesn’t show up, because most of these experiments don’t have anything like that as an endpoint, and it’s just 1/1000 anyway). So regardless of whether testing at a certain level is good or bad, it will always show up as bad on insurance experiments.

You can think of excessive doctors visits as a special kind of overtesting. I see some of my patients more often than I think is medically indicated because they feel more comfortable if they see a doctor more often (I don’t know why). I see others more often than I’d like because they’re somehow unable to send me an email saying “I am sick and we need to meet sooner than scheduled”, so I either have to see them monthly, or see them after three months when they’re on death’s door after having been sick for two months. I don’t understand why patients are like this, but it offers another degree of freedom in “amount of healthcare received” that probably doesn’t look great in insurance experiments.

MrPwrites:

Cut all antibiotic use for ear infection in children or cut it in half. To paraphrase Robin Hanson “Ear infection treatment is not about curing ear infections”.

One type of ear infection in children accounts for 10% of all antibiotic use in Iceland (From the paper 20% of antibiotic use in Iceland is consumed by children under 7 of which 50% is used to treat a type of ear infection.) Relative to other Nords Iceland has a larger problem with antibiotic resistance. - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3442319/.

Instead ear infection treatment is about -

…“the lack of stable doctor–patient relationships due to lack of continuity in medical care. Pressure from patients in a stressful society, the physician’s work pressure, the physician’s own personality, particularly the earnings incentive and service mentality and, last but not least, the physician’s lack of confidence and uncertainty, resulting in use of antibiotic prescriptions as a coping strategy in an uncomfortable situation” Petursson P. GPs’ reasons for “non-pharmacological” prescribing of antibiotics: A phenomenological study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2005;23:120–5.

To which 1123581321 responds:

Have you ever had an ear infection? I’m not trolling, it’s a serious question.

The pain is…. I don’t know what to compare it to, I’ve never experienced anything even close. And it was a bacterial infection, and maybe you’re telling me it would have just cleared by itself, or maybe I’d go with what the doctor told me, that it was quite dangerous because of its proximity to brain, here’s a prescription, you should notice an improvement withing 24-48 hrs., and I did. Take the pills and noticed an improvement.

I think this is a good and important point about medical waste!

IIUC “This treatment saved the patient 24 hours of excruciating pain” wouldn’t have shown up as a positive outcome on any of the insurance studies, even in the subjective self-report questionnaires (which were mostly about current health). It’s very easy for a bureaucrat measuring “outcomes” to think of this kind of spending as “waste”.

There’s an ongoing debate in medicine about whether doctors who respond to patients’ demands to throw the maximum level of treatment at their excruciatingly-painful but temporarily and non-dangerous conditions are good doctors (because they’re listening to their patients perspective) or bad doctors (because they’re letting their patients’ demands overcome good medical practice). Sometimes it’s obviously the latter, like when they give patients medications which don’t work at all, even as painkillers, to shut them up. And I remember that during residency I worked with a doctor whose answer to all painful-but-not-otherwise-dangerous conditions was “nobody ever died of pain”. This guy probably had the lowest medical spending in the hospital, and maybe the lowest side effect rate in the hospital, and probably many other valuable records, but I would not have wanted to be his patient.

This is another thing that just doesn’t show up at all in the insurance experiments.

Michael Bacarella writes:

Don’t statins pretty neatly bust Hanson’s claim?

Heart disease is a top killer. The NNT_5 for the absolute lowest risk group on statins is 400.

NNT_5 is too short even, because statin benefits compound over decades.

Statins are also cheap and well tolerated

Given higher risk groups have a lower NNT, and people will be on them for decades, aren’t we likely saving millions of lives?

The insurance studies had cholesterol as an endpoint, and the good-insurance group never had noticeably better cholesterol than the bad-insurance group. But there was no record of how many extra people got statins, whether statins were having an effect but the studies were underpowered to pick up on them, and I think the latest research suggests statins might have some effect independent of cholesterol. So yeah, I think we don’t know whether insurance causes people to be more likely to get statin treatment, and that’s another plausible route to health/mortality improvements that the insurance studies potentially couldn’t pick up on.

JSelingerwrites:

I’m dying from recurrent / metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (R / M HNSCC_frustrating), so the sections about cancer in particular stand out to me. Regardless of the current state-of-the-art for cancer treatment, personalized and mRNA vaccines are likely on the verge of revolutionizing cancer treatment.

Take the HNSCC that’s killing me: I got a partial glossectomy in Oct. 2022. Mine had some high-risk features, but I was assured that, with radiation therapy, it wouldn’t recur In retrospect, I obviously should’ve done chemo and radiation, but at the time I was pleased to not need chemo, and I foolishly didn’t look deeply into the data on recurrence, which is common for HNSCC, and I didn’t seek second opinions.

Docs are reluctant to impose systemic chemo because of the side effects. But Transgene has a personalized vaccine that is supposed to prevent HNSCC recurrence: https://www.nec.com/en/press/202304/global_20230418_01.html: “In the head and neck cancer trial to date, all patients treated with TG4050 have remained disease-free, despite unfavorable systemic immunity and tumor micro-environment before treatment,” And most of these personalized vaccines have essentially no side effects.

Moderna’s mRNA-4157 platform also looks good: https://jakeseliger.com/2024/04/12/moderna-mrna-4157-v90-news-for-head-and-neck-cancer-patients-like-me/, not only in R / M HNSCC, but in melanoma and lung, too. Right now mRNA-4157 is only being tested in the recurrent / metastatic setting, as far as I know, but the logical time to use it is probably when initial surgeries are done: cut the cancer, sequence it, and then vaccine against it to prevent recurrence.

Right now, from a society-wide perspective, the healthcare I’ve been getting probably fails the cost-benefit test (apart from the fact that the data I’m generating for clinical trials helps move the state-of-the-art forward). My quality of life is low, and while treatment has been extending my life, it almost certainly won’t lead to remission. And even if a clinical-trial drug somehow leads to complete remission, I’ll never be able to sleep or speak normally again (https://jakeseliger.com/2023/08/27/on-being-ready-to-die-and-yet-also-now-being-able-to-swallow-slurries-including-ice-cream/). A few months ago my brother casually referred to me being disabled, and I was momentarily confused: Who was he talking about? But he was in fact right: I’m disabled and unlikely to ever be able to think or work in the way I did before losing my tongue.

But that should change! Part of the reason I’m so frustrated by the FDA is that mRNA-4157 and TG4050 should already be available for HNSCC. Instead, they’re stuck in trial hell, while HNSCC patients like me suffer recurrences and then die.

I appreciate this perspective. We act like “the value of health care” is an objective thing, but people have pretty different values and health care is more important for some than others. Jake seems very dedicated to surviving as long as possible; as he points out, in a cost-benefit analysis, throwing lots of high-tech stuff at a severe cancer patient in order to buy them another year or two seems excessive, but when it’s your life, it . . . might or might not be, depending on what you want.

I’ve seen patients with terminal illnesses who are very happy they chose to just let it progress and not spend their last few years in medical trials, and other patients who are very happy that medical trials gave them another year or two with their family and whatever else they were trying to accomplish. Although Robin’s heuristics at the beginning of the post are good for the median person, you’ve got to decide what you value.

Vitorwrites:

Let me try to steelman the anti-healthcare position here.

I have chronic heart disease. Based on some early symptoms and family history, I was put on several medications (beta blockers, ACE inhibitors). Sounds great, right? However, I have developed chronic fatigue in the years since, which is 10x worse than my (mild) heart problems.

Years into this, I find out that the heart medications I’ve been taking have extremely strong system-wide effects: reduced activation of the sympathetic nervous system (beta blockers), increased inflammatory response and lowered pain threshold (ACE inhibitors), and even reduction in the efficiency of respiration (apparently, lowered heart function, which my meds induce, can lead to slight respiratory alkalosis even as oxygen saturation read as “healthy”). My cardiologists never mentioned any of these effects to me. These don’t correspond to the typical image we have of side effects (rare, acute complications, e.g. “rashes in less than 5% of patients”). Rather, this is cumulative damage to half a dozen vital subsystems, throwing homeostasis way out of whack.

My point is that some outcomes are relatively easy to measure and correlate (early start with heart medications reduces incidence of heart failure), while diffuse downstream effects that sap your vitality and make your life worse are extremely easy to miss, in all but the most egregious cases. If we assume that such things are systematically happening in the treatment of many diseases that aren’t immediately life-threatening, we can end up with a picture where lots of people walk around saying that modern medicine has saved their lives many times over (I used to say such things in my younger days), while simultaneously the health of the population gets mysteriously worse, in ways that are easy to dismiss with a “better screening” pseudo-explanation.

I agree that medicine is bad at detecting “I feel vaguely worse on these drugs”. I try to make sure my patients know that any drug can make you feel vaguely worse (especially psychiatric drugs) and it’s their job to let me know if this is happening to them so we can try to prevent it.

If you take a medication and feel much worse, then unless this is part of the plan (eg everyone knows they’ll feel worse on chemo, but it’s worth it), tell your doctor and unless they have some great counterargument, consider stopping the medication.

In a sub-discussion on US maternal mortality,WindUponWaves writes:

» “Well, the CIA factbook figures on maternal mortality rank the US second-to-last out of the selected countries…”

Funnily enough, even that is more complicated than it first appears: [From] The U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis Is a Statistical Illusion – Accurate counting has produced a seemingly dire death rate:

» “However, these figures are completely wrong, and they have been known to be wrong for many years now. The U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, the branch of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) charged with collating health and vital statistics, has published three separate reports elaborating in excruciating detail on one crucial fact about U.S. maternal mortality: It is measured in a vastly more expansive way than anywhere else in the world.

» As a result, U.S. maternal mortality is overestimated by two to three times. Properly measured, the real U.S. maternal mortality rate in 2019 was 9.9 maternal deaths per 100,000 births, which would put it at 36th place—still not impressive by comparison, but somewhat better than Canada and a bit worse than Finland or the United Kingdom […]

» Historically, the United States and most countries have tracked maternal mortality using data based on the cause of death listed on death certificates. When a person dies and the cause is assessed by an examiner of some kind, certain “maternal” causes, such as “eclampsia” or “obstetric trauma,” are commonly tracked. If a woman has died due to one of these pregnancy-related causes, she is listed as a maternal death. This process is fairly straightforward and has been widely adopted across many countries.

» But in 2003, the U.S. CDC decided to launch an improved death certificate form. Among the various changes proposed was the addition of a checkbox, wherein whoever filled out the paperwork would identify if the deceased had been pregnant in the last 42 days or the last year. The reason for this checkbox was that the CDC believed (correctly, as it turns out) that in only measuring “maternal causes of death,” it might be underestimating the true health hazards of pregnancy. Pregnancy might alter the course of other diseases and conditions or interact with them in important ways.

» The CDC anticipated that the checkbox would increase measured maternal deaths; it did not anticipate just how much it would increase them. As it happens, the CDC’s own reporting, which I have confirmed elsewhere, shows that the addition of the checkbox approximately doubled maternal mortality rates.

» You might think a sudden doubling in maternal death rates would be obviously flagged as a data issue to correct, but this turns out not to be so. Because the United States has a federal system, individual states added the checkbox in different years. While individual state maternal deaths showed sharp level shifts, the national maternal death count drifted upward gradually as states added checkboxes to their death certificates: California in 2003, Florida in 2005, Texas in 2006, Ohio in 2007, Tennessee in 2012, etc.

» In 2018, further modifications were made to the data-processing protocols used by the National Center for Health Statistics for pregnancy-related checkbox deaths, leading to more thorough inclusion of them. The result was a massive but gradual artificial inflation of maternal mortality.

» This doesn’t mean that the American way of measuring death is wrong. It’s just quite different from the countries that it’s being compared to…

» But the U.S. case is particularly beguiling, since the United States now tracks all deaths of women who were pregnant, not only women who gave birth. Women who miscarried early or had abortions—whether officially reported or not—are also counted in the checkbox method. As a result, the United States may be the only country in the world where central vital records systems track all pregnancy-related mortality, not just maternal mortality.”

I didn’t know this, thanks!

Niklas Anzinger (blog) writes:

I’ve read Hanson’s pieces on all of this for quite a bit and talked with him on my podcast here too:

If you’re concerned with the “so what?” question, his clear answer is: bundle healthcare with life insurance, to give providers the incentive to keep you alive. There are a couple of kinks with this idea that he’s worked out, of course there are practical challenges that we don’t know yet how they will play out. But the upshot of it is: this healthcare-insurance bundle provider would have the right incentives to figure out which half of medicine is bad, and which is good (i.e. efficacious).

It seems there is a bigger question, one that Robin does not address at length, about the efficacy of clinical research. I’m not deep into the details, but the replication crisis may affect it. The incentive for pharma after a successful clinical study that leads to FDA approval is to not ever question the results and sell as much of the drug as they can. As far as I understand, they have no liability after approval. Doctors also don’t seem to have the right incentives (which I can’t describe from experience or with sufficient detail, but from what I understand it also has to do with liability / malpractice lawsuits).

Okay, I was pretty on board with maybe I was just strawmanning Robin and he thinks most medicine works and it’s just that we overspend at the margin — but the podcast is called “Most Drugs Are Bad For You”! Someone who listens to podcasts - is this just mistitled? Part of my frustration here is that Robin is saying reasonable things, but summaries of his work keep getting titles like “Health Care Is About Signaling” or “Most Drugs Are Bad For You”. If nothing else, hopefully this exchange will get title-makers to ask Robin if that’s really what he means before calling summaries that!