Highlights From The Comments On Housing Density And Prices

Original post:Change My Mind: Density Increases Local But Decreases Global Prices

Table Of Contents:

1. Comments About Whether Density Causes Desirability

2. Comments About Jobs And Amenities (And Not Density Per Se) Producing Desirability

3. Comments About Chinese Ghost Cities

4. Comments Accusing Me Of Not Considering Tokyo, Even Though I Included A Section In The Post On Why I Didn’t Think Tokyo Was Relevant

5. Comments Accusing Me Of Not Understanding Economics

6. Comments By Famous People Who Potentially Have Good Opinions

7. My Final Thoughts + Poll

1. Comments About Whether Density Causes Desirability

Many people accused me of not understanding that correlation isn’t causation, or that supply is different from demand. For example, KronoriumExcerptC from the subreddit:

He says that maybe some of it is explained by reverse causality, but this just seems to be the obvious explanation for the entire thing. Of course places that are more expensive are going to build more- otherwise they’d be even more expensive. If you can demand the highest rent prices, of course you would want to build houses in those locations.

PB34:

Right. A third thing is causing BOTH the density AND the high prices: NYC is very desirable to live.

This means that prices in NYC are very high due to high demand. It also means developers are extra incentivized to build there, knowing their housing will certainly be filled.

It ALSO means that people will put up with worse living conditions (tiny apartments, little personal space, all the little indignities associated with density) in order to live there.

It feels like, why are you guys arguing if A causes B or if B causes A? It’s clearly C that causes both of them…

I tried to explain my thoughts on this on the original post, but let me try harder:

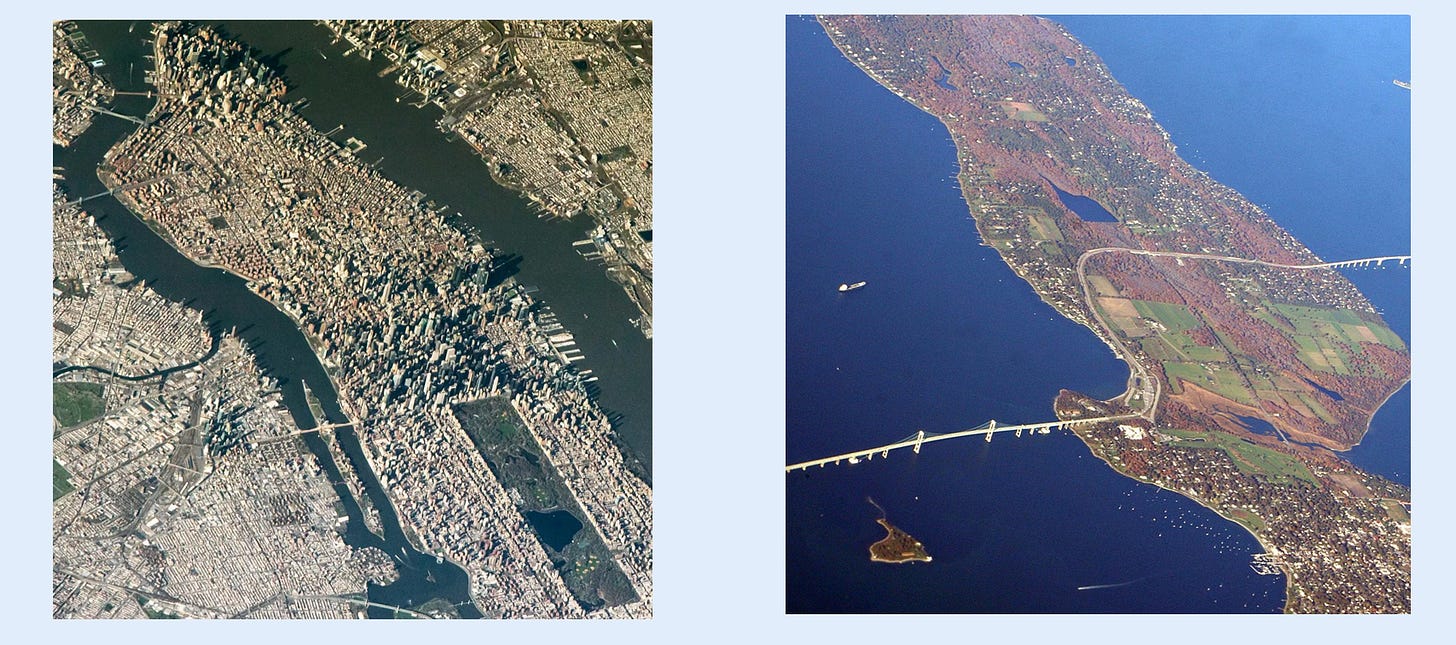

The picture on the left is Manhattan Island, NY. The picture on the right is Conanicut Island, RI. Both islands are about the same size, the same climate, the same distance from the mainland. Both are near good natural harbors. In 1600, some early European explorer would have considered them basically interchangeable.

Still, the cost of housing in Manhattan is about $2000/sqft, and the cost of housing in Conanicut is about $500/sqft. Why? God didn’t create these two islands with different land value; something must have happened to make one 4x as expensive as the other.

The obvious answer is “the Dutch chose to build their colonial capital on Manhattan, more and more people moved in, it became ever denser and more urban in a virtuous cycle, now it is very dense and urban, and, in the current regulatory regime, dense urban areas have higher housing prices than empty rural ones.”

If back in 1624 the Dutch had decided to build their capital on Conanicut, maybe today it would be a city of 10 million people, and Manhattan would be an empty rural area. In that case, I would expect Conanicut to have 4x the house price of Manhattan.

If I were a Native American living on Manhattan, and I was committed to keeping housing prices there low, I would ask the Dutch to build their capital on Conanicut instead. In fact, whenever a European came to my island seeking to build houses, I would try to fight them off. If I somehow succeeded at this for four hundred years, and Manhattan remained an empty rural area, then I would expect Manhattan prices to be much lower than they are now.

So in response to all of your comments that I don’t understand basic causal inference, I answer that history provides quasi-experiments, and no, I’m pretty sure that Manhattan has high prices because lots of people moved there, rather than because of some other factor. Or, rather, both density and desirability feed into the other, but the density step is a crucial input.

2. Comments About Jobs And Amenities (And Not Density Per Se) Producing Desirability

But Martin Blank writes:

NYC/SF are expensive because there are MANY good jobs there and people WANT to live there. Not because of the density of housing. You could build 500,000 homes in the middle of your empty field in North Dakota, and it wouldn’t do much for the demand there. You aren’t going to create Manhattan by magicking 3.5 million housing units of similar quality into the Red Lake Indian reservation in Northern Minnesota.

I originally found the various comments saying this annoying. Yes, there are many good jobs in NYC. You can be a barista at Starbucks, you can be an actor on Broadway, you can be a train conductor for the MTA. But why is it easier to be a barista in NYC than in North Dakota? Surely because there are millions of people in New York, those people drink a lot of coffee, and so they need a lot of baristas. Likewise, they watch a lot of plays, and ride a lot of trains, so they need actors and train conductors. If all the residents moved to North Dakota, there would be lots of demand for baristas, actors, and train conductors in North Dakota, and none in NYC.

But some people gave versions of this argument that I found harder to dismiss. JSwiffer writes:

The key fact your missing is if you wave a magic wand and 10x San Francisco you wouldn’t 10x all jobs. You would 10x the # of waiters, and garbage men but you wouldn’t 10x the # of 500k/yr Google site reliability engineers. And it’s the latter not the former that are driving up prices.

Other commenters analogized this to factory or coal mining towns.

Here’s how I ended up thinking about this: suppose someone strikes oil in an uninhabited part of North Dakota, enough to produce 1,000 good oilman jobs. 1,000 oilmen move to the area and start a town. Because there are no NIMBYs, they build 1,000 houses.

Each oilman creates demand for a certain amount of waiters (to serve them food), doctors (to treat their illnesses), teachers (to teach their children), etc.

How many waiters, doctors, teachers, etc move to the town? Assume for the sake of argument that all jobs earn the same salary, $50,000. In that case, it has to be fewer than 1,000. Each oilman earns $50,000, and some of that gets spent on taxes and out-of-town goods. So he has less than $50,000 to spent on in-town goods and services, so (in this hypothetical) creates less than one other job.

Each waiter needs doctors to treat their illnesses and teachers to teach their children, so each service employee creates some number of additional service employee jobs.

Makeshift housing in a North Dakota oil boom town (source)

Makeshift housing in a North Dakota oil boom town (source)

If each person creates half a job, the original 1,000 oilmen attract 500 service workers, those 500 attract another 250, and so on until population stabilizes at 2,000 people.

In this model, if there are fewer than 2,000 houses in the town, demand exceeds supply (no matter what is going on in the rest of the country), but if there are more than 2,000, supply exceeds demand.

So if we imagine Google’s presence as an oil-like resource, the extra demand for housing in the Bay should gradually decline: at some point, you will have finished housing the Google workers and the service workers who support them.

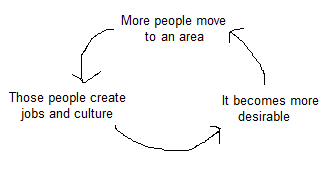

But this isn’t right either, because Google isn’t a natural resource - it’s a company founded by Bay Area residents. If you got more Bay Area residents, you would (with some delay) get more Googles.

Or: Austin gets lots of jobs from Tesla. Tesla wasn’t founded by Austinites. But it moved to Austin when it became a known “tech hub”, ie a place with lots of tech companies and tech employees. It wouldn’t have moved to Austin if Austin was still an uninhabited plain or a one-horse town. So as Austin got bigger, it attracted more tech companies.

So in both the Bay Area case and the Austin case, having more people attracted more tech companies, either because the residents themselves found the company or because the company gets attracted to this newly bustling city.

Potential counterargument: Each new Bay Area resident gives the Bay another lottery ticket to found the next Google. If having the first Google gets it an extra 1 million people, but there are 300 million people in the US, then those extra 1 million only give it a 1/300 chance of winning the next lottery. So even though the Bay Area won the lottery once, and this made it have high demand, this doesn’t mean the high demand will cause it to win more lotteries. If you win the lottery once, spend all your winnings on more lottery tickets, and keep doing this forever, you haven’t invented an infinite money printing machine, eventually you’ll just lose.

Potential counter-counter-argument: the Bay got Google, and Facebook, and Apple, and . . . so these can’t all be separate lotteries. I think you should probably model it as a high-level lottery to become the next hub of a tech-sized industry, plus many low-level lotteries where once you’re the tech hub, you’re attracting lots of techies, and each techie gives you a ticket in a lottery where the denominator is the number of techies to found the next big tech company. And the Bay might have half the US’s techie population. So maybe here there is a self-sustaining lottery-winning cycle, at least until tech plays itself out and nobody wants any more tech companies. And that might take a long time.

Tom (author of Tom Thought) writes:

The primary drivers of demand for living in NYC are the specific opportunities available in NYC. It is true that on long time horizons, one of the reasons these opportunities have tended to collect in NYC is that it is a dense place. But those aren’t the only reasons - NYC is much more important than other, bigger cities in other parts of the world for complex historical reasons. Even if a catastrophe were to wipe out half the city, there would still be a great deal of demand to live near important institutions like Broadway, Wall Street, Port of NY & NJ, Columbia, etc (assuming those institutions survived the catastrophe).

Increasing the number of housing units has a very mechanical impact on how many people can live in the place. But it has only a second-order impact on the types of institutions that drive demand to live in the city. People don’t just generically crave to live near other people for the most part (a handful of urbanist freaks like myself excepted).

The Bay Area is a great example of this. It is much less populated than other much cheaper cities. Density isn’t why people want to live there - it’s access to a specific culture and specific institutions. Demand for that is not simply a function of density - some people want to be part of Bay Area culture and others don’t. Adding more units will induce some demand as a second-order effect, but will bring prices down as a first-order effect.

To relate this to your model: we might be able to say that the country has a certain number of abstract “culture points” that have been allocated to different cities by various historical forces. Each culture point a city has increases demand to live in that city by a certain amount. Adding more people to the city may allow it to generate additional culture points over time, or acquire culture points from other cities, but this doesn’t happen right away, and is determined by a host of factors other than just density.

Under this model, we expect a place like NYC to always cost much more than North Dakota (since NYC possesses a large number of culture points), but we would also expect that adding additional housing units to NYC would bring costs down (since there are now additional housing units per culture point). Perhaps this process will over time allow NYC to steal away some culture points from Chicago, Boston, or other cities, but this is a secondary effect.

This just seems to be passing the buck. Yes, people move to New York because it has Broadway, Columbia University, and Wall Street. Why does it have those things? Because one in every X New York citizens founds a good artistic/educations/financial institution, and New York has a large population of employees to work at those institutions and customers to patronize those institutions. If Conanicut Island had a population of 10 million people instead of Manhattan, there would be lots of great institutions on Conanicut and it would have more culture points. I don’t think it’s a culture-point game and population/density just sort of occasionally redistributes culture points, I think to a first approximation culture points just track population/density. Maybe they track the population/density of upper class people better than the total population/density, but I don’t think this is a big enough distinction to sink the argument.

3. Comments About Chinese Ghost Cities

Some people brought these up as a good natural experiment: the Chinese really did try building millions of houses on their equivalent of a North Dakota plain. What happened?

Jeremiah Johnson (author of Infinite Scroll) writes:

You currently seem like you’re at the stage of understanding the thought experiments pretty well, but not understanding them on a DEEP level. For example with your hypothetical, this has actually happened before! Kind of. China built a bunch of ‘ghost cities’ basically out of nothing, and while there was an initial craze of speculation and tons of investment and building… nobody went to live in those cities most of the time. And now they’re deeply distressed assets worth basically nothing. When nobody actually lives in the ghost city, it doesn’t matter that they have super dense housing. There’s no demand. (the only reason they might be worth something is that the CCP very, very much does not want to pop their huge housing bubble and is likely to bail out some of the parties involved)

Parmenides (author of Last House On The Left) writes:

I think your mixing up the agglomeration effects of density, which is what induces the demand, and the housing supply. You can’t just build a city and expect people to move in, China has tried that. But if you have the agglomeration effects of density and shortage of housing due to artificial constraints, which we have all across the US, then you get dense areas with high housing costs.

sdwr writes:

Think of China’s ghost cities / apartment blocks. Prices surely can’t be that high there. Maybe the answer is that developers are good at their job, and build supply where theres demand for it?

But several other people object that although the Western press made a big deal about Chinese ghost cities a few years ago, it mostly just took a couple of years for people to move in, and now at least some of them seem to be thriving. For example, Michael quotes the Wikipedia article, Under-occupied Developments In China:

Reporting in 2018, Shepard noted that “Today, China’s so-called ghost cities that were so prevalently showcased in 2013 and 2014 are no longer global intrigues. They have filled up to the point of being functioning, normal cities”.

Ash Lael writes:

I’m sceptical of the Chinese “ghost city” phenomenon. I haven’t explored the issue rigorously but my impression is that in areas that were previously dismissed as “ghost cities” like Ordos Kangbashi, the population is now large and growing.

I think we in the west are so used to infrastructure bottlenecks and short sightedness and anti-construction policies that the idea of it being possible to build the housing and infrastructure to accomodate expected demand ten years in the future is completely foreign to us. Perhaps building brand new cities before they are even needed is what the YIMBY utopia looks like.

See also Bloomberg: China’s Ghost Cities Are Finally Stirring To Life After Years Of Empty Streets.

This wasn’t trivial. It looks like the Chinese government had to put in some work to make people move in, including opening good schools and universities there. Probably if they had just built apartments in the middle of the desert and nothing else, they would have stayed empty. But that’s even more of a reductio ad absurdum than the original ghost city plan.

Kangbashi, China’s most famous ghost city.

Kangbashi, China’s most famous ghost city.

What are housing prices like in the ghost city? Again from Bloomberg:

Sitting on the southern outskirts of Inner Mongolia’s Ordos City (population 2.2 million), Kangbashi was the archetypal ghost city 10 years ago, with barren boulevards and empty buildings standing forlornly in the desert. Local officials are adamant that things have changed. They say 91% of homes in the district are occupied. In fact, after a yearslong construction freeze, the government approved six housing projects in 2020 and expects 3,000 homes to be built by the end of this year.

Apartments in a new development are selling for 9,500 yuan per square meter, and downtown they go for 15,000 to 16,000 yuan, according to Liu Yueyue, 28, a salesman at a new residential development in the district’s northeast. “Would houses in a ghost town sell at such high prices?” asks Liu. Half of his customers come from outside Kangbashi, and most are parents who want to send their children to the well-regarded local schools, he says.

Looking at this list of real estate prices across Chinese cities, Kangbashi seems squarely in the middle - for example, Wuhan and Xian are also in the 15,000 - 16,000 range.

I claim this supports my argument: surely twenty years ago, houses in this particular deserted corner of Inner Mongolia would have been dirt cheap (if any even existed). But if you build a city there, it becomes just as expensive as any other city! Here it’s very obvious that the density caused the high prices instead of the other way around.

Still, the Chinese housing market is weird, with significant vacancies even in expensive, well-developed cities. Paul Botts:

No official vacancy rates are published in China and no specific definition of it exists there. Various think tanks and researchers both within that country and elsewhere have published estimates ranging from as low as 11 percent to as high as 24 percent. Those estimates have been for varying samples of Chinese cities, have used various definitions of housing vacancy rate, etc.

The best (as in most systematic) estimate yet produced has come from researchers at a university in Liaoning. They used night-time urban lightsheds captured by a new (2018 launch) Chinese satellite having a new level of light sensing technology which allows separating out light from parks and plazas. They covered a large sample (49 cities), and made their sample representative of city type, city size, regions within China, etc. They also crossed-referenced with local housing data to ensure accurate balancing of their sample and to confirm that the satellite was successfully identifying light coming from housing blocks.

They found vacancy rates of just under 20 percent in China’s Tier 1 cities, and found rates above 20 percent in 40 of the 49 cities. They found the highest vacancy rates in western and northeastern cities, which are also the newest ones; that finding is consistent with the hypothesis of significant numbers of recently-built ghost cities.

And Phil H (author of the blog Tang Poetry) writes:

The price of housing in China has skyrocketed over the past few decades, as all those extra apartments have been built. I live in a pleasant but unremarkable southern city, and I paid London prices (about 4.5m yuan/$650k for a 1,300 sq ft flat). That seems to match Scott’s hypothesis that high density leads to high prices. House prices here have risen much faster than incomes. They’ve risen in rural areas, too, but the increases in price in cities have been stratospheric.

4. Comments Accusing Me Of Not Considering Tokyo, Even Though I Included A Section In The Post On Why I Didn’t Think Tokyo Was Relevant

I won’t name and shame people, but for example:

You excluded Tokyo from your dataset. Tokyo has much higher density than SF and much lower price per sqft.

Tokyo just kills this. Tokyo is bigger than New York and has significantly lower rent because they build more housing! This is in a wealthy country with even lower interest rates than the US.

I don’t think you have justified excluding non-US metros, like Tokyo, or Auckland. Doesn’t this lead to the natural conclusion that there is a sufficient level of housing to build, and that the problem is that the USA’s many metros are structured to prevent housing? It seems like you’re just arguing that US metros are bad at building housing, which is also what Matt Yglesias is arguing.

“Change my mind about housing, but don’t mention Tokyo” is like saying “Change my mind about gun possession, but don’t mention Switzerland.” You can’t test the effect of allowing new housing unless you’re willing to look at cities that do, in fact, allow it.

Tokyo and NYC both attract tons of new residents But Tokyo’s housing rents have been stable, while NYC rents keep rising. Why? Tokyo has permissive housing construction laws. NYC makes building new housing almost illegal. Yes, dense cities are attractive, and that makes them get more dense over time. But it only makes them more expensive if you forbid new housing to keep up with the new residents.

Tokyo! But I’m like the 10th person to bring it up…

As I wrote on the original post (not even edited in! it’s been there the whole time!):

I worry someone will bring up Tokyo as a counterexample. But I think Tokyo managed to build its way to low housing prices in the context of the rest of Japan also having good housing policy. Even if that isn’t true, Tokyo on its own is a quarter of the Japanese market, so it might be able to exhaust the entire pool of Japanese house-seekers by itself!

That is, yes, you’re all correct that cities are only expensive in the context of more demand for city housing than the (NIMBY-constrained) city housing market can currently supply. You are all correct that if this problem were solved at the national level, then city housing would be cheap, and every additional city house would make it cheaper.

My claim is that marginal changes - like Oakland building an extra 10,000 units, but everyone else staying the same - will most likely increase Oakland prices. Yes, if Oakland unilaterally built 50 million units, that would soak up the entire excess demand and probably lower prices everywhere (including Oakland). Yes, if the entire US switched to good housing policy at the same time, that would probably lower prices everywhere (including Oakland). But if we don’t do any of that stuff, and just build another 10,000 houses in Oakland, I think it would probably increase prices in Oakland.

Some other people brought up that Japan has a declining population, and it’s much easier to have low house prices when your population is declining (compared to some previous time when number of houses presumably matched number of people), but ddd pointed out that people continue to migrate from the Japanese countryside to Tokyo, so its population continues to increase.

Also, Mike (I’m stitching together two comments here):

In a country with a declining population, you would expect that fewer homes are being built per capita because there’s little to no competition for existing homes. But it’s exactly the opposite! Japan builds far more homes per capita than the US does, despite their declining population […] As a result, the average Japanese home is very new and the average house is torn down and replaced after a relatively short 30 years. They’re living in nice new homes for cheaper.

5. Comments Accusing Me Of Not Understanding Economics

Maximum Limelihood Estimator writes:

I think you’re making a very common mistake here of confusing supply/demand with quantity supplied or quantity demanded. (This is very common! we teach students about this in micro 101 because it’s so easy to make!)

What you’re seeing is that the quantity supplied is correlated with housing prices (true!). But this is very different from establishing that the supply curve–i.e. the amount of housing that would be produced at any given price, and what moves up/down when we regulate/deregulate supply–is positively correlated with price. Figuring out what supply curves look like is a lot less intuitive and requires some high-grade econometrics, which is why economists had to set up a whole commission just to study this particular problem (the Cowles Commission).

In terms of resources for understanding how these concepts are different, a micro 101 textbook will cover this distinction. For the econometrics side of this, I’ve heard good things about Scott Cunningham’s Causal Inference Mixtape, although I haven’t personally used it.

My claim is that increasing density within a city shifts the demand curve for housing within that city, because of increasing desirability.

MLE later gets more on point:

The effect you’re discussing here is kind of real in a sense. When the marginal utility of housing increases for other people, density arguably becomes more desirable for me, which is kind of like the demand curve shifting up. These are called bandwagon goods and discussed here:

http://econfac.bsu.edu/research/workingpapers/bsuecwp200804gisser.pdf

In theory, the bandwagon effect could be so strong that parts of the demand curve are upward-sloping. Solutions like this are not, technically, prohibited by the laws of mathematics, just the laws of economics. (And arguably of physics–see paper for conditions where these kinds of bandwagon effects imply the amount of housing in the city would have to be negative).

In practice, this effect exists but just can’t overcome the normal, non-weird economics that says “making more of a good makes the prices fall.”

Again, I claim the existence of Manhattan vs. Conanicut shows that sometimes it does. I cannot find the words “housing”, “real estate”, or “land value” anywhere in that paper.

Alex Poterack writes:

There’s two things going on here: confusing shifts in demand with movement along the demand curve, and getting causation backwards.

You’re assuming density causes prosperity, rather than prosperity causing density. There are ways the former can happen, but the bigger thing is that, for a wide range of historical reasons, you can make a lot of money in NYC and SF, so lots of people want to live there, so they get very dense. This is the prosperity shifting demand right, so at any given price, more people want to live there; this drives prices up, and they go higher the more fixed supply is.

If you built a bunch of housing in Oakland, lots of people would move there because it’s cheaper, which is movement along the demand curve; it’s still the same number of people who want to live there at any price. Now, it’s possible that the increased number of people living there makes the city more prosperous (this is the phenomenon of induced demand), which would shift demand right, but there are way more differences between NYC/SF and Oakland than just the density, so I don’t think it would shift demand enough to offset this. In particular, if it’s just a small increase in small, it’s also a small increase in density, so there’s almost no shift in demand (but there is movement along the curve).

I still think this is missing my point, but I present it here in case anyone else is enlightened by it and wants to try further to convince me I’m making this mistake.

6. Comments By Famous People Who Potentially Have Good Opinions

Scott Sumner is an economist and blogger; he writes:

It is certainly the case that building more housing can make a city more desirable, and that this effect could be so strong that it overwhelms the price depressing impact of a greater quantity supplied. But studies suggest that this is not generally the case.

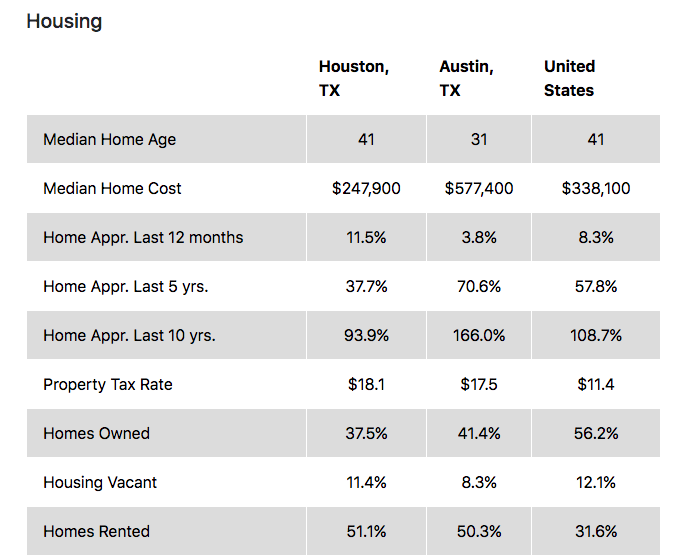

Texas provides a nice case study. Among Texas’s big metro areas, Austin has the tightest restrictions on building and Houston is the most willing to allow dense infill development. Even though Houston is the larger city, house prices are far higher in Austin :

Houston pretty much describes the “Oakland with more housing” outcome that Alexander views as somewhat far-fetched. Only in this case, it’s Austin with more housing. Alexander seems too quick to accept the, “If you build it they will come” idea—that you can build more housing and thereby boost demand so much that prices actually rise.

I started the post with a graph of about 50 cities, showing a positive correlation between density and price. I’m having trouble seeing how Sumner’s point isn’t just “if you remove 48 of those cities and cherry-pick two, the relationship is negative”.

My attempt to place Austin and Houston on the original graph, using Sumner’s data plus a few other things available online. Why weren’t they on there already? Maybe because the graph is metro areas and Sumner was talking about Austin and Houston as cities, but I’m not sure and agree this is confusing.

My attempt to place Austin and Houston on the original graph, using Sumner’s data plus a few other things available online. Why weren’t they on there already? Maybe because the graph is metro areas and Sumner was talking about Austin and Houston as cities, but I’m not sure and agree this is confusing.

Everyone knows Austin is more expensive than Houston because Austin is a trendy tech and culture hub and Houston isn’t (and relatedly, because Austin’s median family income is 50% higher than Houston’s). Unless someone wants to claim that its failure to build housing helped turn it into a trendy tech and culture hub, I don’t think there’s much point to this comparison.

It’s true that Houston’s bigger size didn’t let it leapfrog over Austin to become a trendy tech and culture hub, which goes against some of what I claimed in the first part of this post. But I never claimed there would be a perfect 1-1 correlation between city size and trendiness, or that you could never find a pair of cities where one was bigger but the other was more trendy. Just that there would be a correlation.

Moving on:

Here’s the problem with this argument. It mixes up population change due to economic effects such as the benefits of agglomeration, with population changes due to regulatory changes such as less strict zoning. If you look at things this way, then the stylized facts work against Alexander’s argument. Over the past 50 years, increasingly strict zoning has reduced housing construction on big cities like New York and San Francisco. As a result, their populations have increased by less than in cities with less strict zoning, such as Houston. If Alexander were correct, then the price gap between the tightly controlled cities on the coast and the more laissez-faire cities of Middle America should have shrunk over time. Instead, the price gap has widened. New York and San Francisco were always more expensive than other cites, but with tighter zoning and less new construction the gap has become far wider.

During the last fifty years, there was also deindustrialization and demographic sorting. This is just the Austin vs. Houston story all over again.

Alexander is implicitly viewing this outcome as a “problem” for the city that builds more housing. They must sacrifice so that the rest of the country can gain. But in his scenario, Oakland is better off. Indeed if it were not better off, then why would more people choose to live in Oakland? In order for it to be true that building more housing boosts housing prices, it must also be true that the quality of existing houses (including neighborhood effects) rises by more than enough to offset the increase in supply. That means the new housing construction must make Oakland such a desirable place to live that the amenity effect overwhelms the quantity effect […]

Of course, economic change always has winners and losers. Here’s how I would describe the impact of allowing more housing construction in Oakland, in the unlikely event that this did raise housing prices:

1. America would benefit.

2. Oakland would benefit.

3. Poor people in America would benefit, in aggregate.

4. Affluent people in America would benefit, in aggregate.

5. Homeowners in Oakland would benefit.

6. Some renters in Oakland would benefit (from a more economically dynamic city.)

7. Some renters in Oakland would suffer from higher rents.In the much more likely case where new housing construction would lower prices, the impact described in #5 and #7 might reverse. Either way, there is no defensible argument for not building more housing in Oakland, regardless of the impact on price. If building more housing reduces its price, then there is a strong argument for allowing more housing construction. If building more housing raises its price, then the argument for more construction is even stronger.

I agree with all this.

Jeremiah Johnson is a co-founder of the Center for New Liberalism, host of the Neoliberal Podcast, and a YIMBY activist (not to be confused with Jeremiah “Liver-Eating” Johnson, who killed 300 Native Americans and ate their livers). He writes:

Here’s why you’re wrong in a single sentence: Demand causes high prices, not new units.

Prices are high in SF and NYC because those are desirable places to live for a huge number of people. People all over the country and the world would live there if they could, and prices reflect that. The fact that the densest cities are the most expensive is true. But the high prices are not caused by density - rather, the density and the high prices are both a consequence of crushingly high demand […]

There’s a feedback loop, but what matters here is the elasticity, which is less than one. We can measure this empirically.

New housing lowers prices via the mechanism of adding supply, which is basic economics and how we expect markets to work.

New housing could raise prices if it also made the city a more desirable place to live and shifted people’s preferences, such that there was more demand to live there after the new housing is built.

If you think it’s unclear which of these effects would dominate, luckily we have empirical data that over and over and over shows adding housing supply does indeed lower prices on a local level. This is a fairly well established result that replicates well.

edit: I’m actually thinking about drawing out the weighted DAG graphs here to make the conceptual stuff easier, but it would be pretty long. I’d love to do this as a guest post.

I’m skeptical of the empirical results because they don’t match the much stronger “Manhattan vs. Conanicut island” empirical results, and if I try to think about why, the best explanation I can think of is that the Manhattan experiment has been going on longer (ie long enough for Manhattan’s extra residents to found businesses and institutions that attract new people).

I’ve told him he can try pitching this guest post to me; in either case, I would be interested in seeing the graphs.

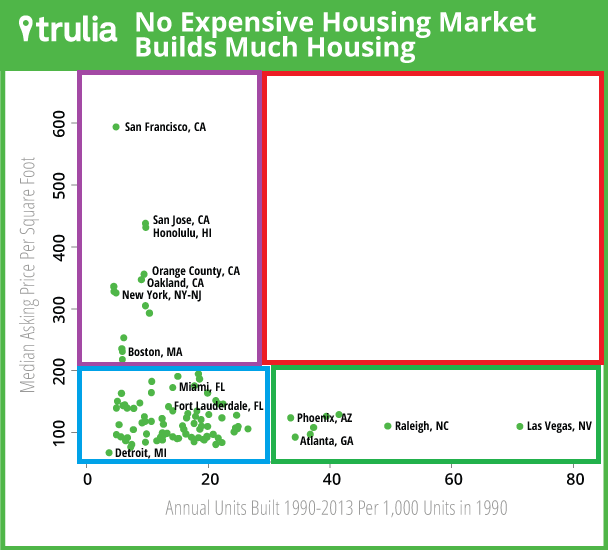

Several other people also posted this graph that Johnson helped make famous:

Hopefully by now you can predict my objection: the places in the southeast corner are mostly unfashionable red state Sun Belt cities; the places in the northwest corner are mostly trendy liberal coastal cities. My conclusion is that trendy liberal coastal cities are both more NIMBY and more desirable, and if you use this to draw any conclusions about housing policy you’ll just end up confused.

But maybe I should take this same lesson to heart myself. Dense cities are mostly trendy liberal coastal cities; uninhabited tundra in North Dakota isn’t. Maybe the demand is just for trendy liberal coastal cities, and once you attain that status, extra density doesn’t matter that much. Maybe Oakland has already maxed out its “trendy liberal coastal city” status, and even if it became Manhattan-sized, it wouldn’t get any trendier, or would get trendier only with a long time lag.

There are a few very trendy small coastal villages in California (think eg Sea Ranch); maybe these (rather than North Dakota) are the natural control group for San Francisco. I think they are still cheaper than SF, but maybe not by very much.

Cameron Murray is a housing economist whose work some other commenters recommended; he also writes the blog Fresh Economic Thinking. He very kindly showed up and wrote:

I think you are in general right that agglomeration effects are real, which is why bigger cities have higher value to residents. I agree that people move locations. But I think you can go a step further. If one city is growing faster and densifying, surely those people are not demanding homes in other cities and those cities build slower. This is part of the spatial equilibrium story that further makes claims about “build density and get cheap homes” less plausible.

7. My Final Thoughts + Poll

Thanks to everyone who commented on this post and helped me refine my thoughts.

I’m willing to concede the following points:

-

It might be that only attracting the sort of educated people who found companies, universities, etc will make housing prices go up. Less educated people will take more jobs than they create and not ratchet up the city’s desirability level. (I’d previously told commenters talking about “gentrification” that it was irrelevant to the mechanism I was talking about here, but maybe it isn’t - maybe “gentrifiers” are the people creating more jobs and institutions than they consume, and so homes that attract them in particular will increase demand more than they increase supply? Maybe this discussion does reduce to the gentrification discussion?)

-

There might be a very long lag between adding new people and adding more desirability, maybe measured in decades, maybe long enough that we can hope our housing problems will have been solved some other way before we have to worry about it. Cities might be able to “outrun” aggregation effects by building houses more quickly than new residents can contribute to the city’s desirability.

-

If a city only built new houses, but refused to allow any new companies, restaurants, schools, museums, or other good things, then the new residents would have a hard time improving the city’s desirability, and house prices would go down. I don’t know how realistic this is or how closely existing commercial regulatory easing tracks residential regulatory easing.

-

It might be that, although trendy cities have (in the current regulatory regime) higher housing prices than empty land or villages, some cities are blessed with perpetual non-trendiness and no amount of density will change this, and other cities have already maxed out their trendiness level and getting denser won’t make them any worse. Maybe my argument applies more to turning empty land into a city (if and only if that city would be trendy) than to making an existing small city into a big city (there’s no sign of this being true in the graphs, but the graphs could be confounded; maybe each city is assigned a trendiness score at birth and never changes).

-

Building new housing in certain cities with specific windfalls (eg Wall Street in NYC, tech in the Bay) might absorb the windfall faster than it produced new windfalls (eg building new houses in SF might make prices lower by successfully housing all existing Google employees, without necessarily producing new Googles). This depends on global factors like how hard it is to make the next Google, how many new Googles the world economy has room for, and how much of an advantage San Francisco has over Cleveland or China in being the most likely location for the next Google.

Maybe all of these together mean that my argument is irrelevant for most cities at most time scales we care about, even if it’s potentially true in theory sometimes.

And although I believed these all along, here are some other things I still believe, in case you missed them the first time around:

-

Building more houses anywhere decreases average cost everywhere and is net positive for global welfare.

-

Building more houses generally improves welfare for the people in the city where they’re built, even if this might come in the form of better living rather than lower rents.

-

If enough cities build more houses, it will exhaust the excess demand for cities, and from then on building houses will lower local rents.

I’m curious to hear what people think, so I’m including a poll at the end of this post. The question is:

Suppose the city of Oakland, California, was randomly chosen for an experiment in which they had to build 25,000 extra market-rate housing units per year beyond their current plan, with proportional increases in the number of office buildings, schools, etc. In terms of style, quality, location, etc, these homes would be distributed in exactly the same proportion as the city’s existing housing stock. If two people moved into each of these units, this would bring Oakland’s population from ~500,000 now to ~1,000,000 at the end of the decade. Suppose that every other city continues its current policy during this time.

At the end of the ten years, you would expect housing prices (compared to an alternate Oakland that didn’t perform this experiment) to be:

1. Less expensive

2. No strong beliefs, it depends on various other factors that could go either way

3. More expensive

Vote here , I’ll report results in the next Open Thread.