Highlights From The Comments On Mentally Ill Homeless People

Table Of Contents

1: Responses To Broad Categories Of Objections

2: Responses To Specific Comments

3: Comments By People Who Have Relevant Experiences

4: Closing Thoughts

1. My Replies To Broad Categories Of Objections

Many of you had strong feelings on this one. As usual, you were wrong.

The first broad category of response was people who got angry at me because they thought I was saying homelessness was unsolveable and we shouldn’t try and you’re a bad person if you’re trying.

That’s not what I’m saying! I’m saying that there are some options, and we should debate them, but people have to specify them first. “Be tough” is a vibe, not a plan.

Plans will have to navigate tradeoffs around potentially not working, potentially being too weak, potentially costing too much money, and potentially being too draconian. I would like to see what tradeoff people choose. I don’t think a proper response to being asked to show your work is “YOU SAID IT’S POSSIBLE TO BE TOO DRACONIAN, THAT MEANS YOU LOVE CRIME AND ARE EXCLUDED FROM THE CONVERSATION!”

At the end of this post, I’ll list some possible plans commenters mentioned. Some of them are decent. I’m happy to debate those plans, but so far the debate hasn’t risen beyond the level of “Well, I would BE REALLY TOUGH!”

The second broad category of response was people who have grand plans for how many new institutions to build and how big those institutions would be. I think this misses the point. The problem isn’t exactly a lack of institutions. If nothing else, there’s always prisons - they’re not very humane, but they’d get the job done.

Why hasn’t the legal system already sent disruptive homeless people to prison? If you understood that, you’ would understand why - if you just built bigger, shinier institutions - the legal system wouldn’t trivially send people to those ones either.

I think the main problem is that homeless people mostly commit frequent low-level crimes that police mostly don’t see and victims mostly don’t report. Prosecutors don’t want to spend $50,000 to have a big trial to put a homeless person in jail for 90 days for disturbing the peace or whatever, and even if they did maybe the cop would admit that he can’t tell homeless people apart, can’t prove it was this particular one who did the peace-disturbing, and the whole thing would fall apart.

People think that “asylums” solve this because you just have to prove that someone is mentally ill, but this is also hard (will police be walking around administering the PANSS to everyone they see in a tent)? Even with the recent Supreme Court Grant’s Pass decision, there are a hundred finicky laws and precedents determining who you can and can’t arrest and for how long. I would like to see whether your plan involves pretending these don’t exist, or a concerted campaign to bring each one to the Supreme Court and overturn them, or what.

Again, this isn’t an unsolveable problem, but the solutions involve more thought than just repeating “BUT I WOULD BE TOUGH AND NOT SOFT” one thousand times and talking about how many stories high your new institutions would be. I would like to know what people’s proposed solutions are so I can assess them.

The third broad category of response was people who objected that surely this problem is solvable, because other countries solve it. The past solved it! California c. 2020 is the only society that has this level of problem with homelessness. We need to be ambitious and believe in ourselves!

Okay, but other countries solve crime without mass incarceration. France/Germany/Britain have 20% the incarceration rate that we do. So why don’t we eliminate 80% of prisons and use handwave handwave welfare social services to handle the former inmates? Now conservatives will start mumbling about American exceptionalism blah blah blah.

Or consider high-speed rail. A decade or two ago, California voted to construct a world-class high-speed rail system linking the whole state. Conservatives warned this would be a horrible boondoggle. But cheap, high-quality high-speed rail is definitely doable. Japan does it! France does it! America created a 3000 mile Rockies-crossing Transcontinental Railroad in f**king 1869, don’t tell me we can’t do rail! You’re just a defeatist who thinks we can’t do things other countries do easily.

Still, the conservatives were totally right. The state put tens of billions of dollars into the project and still hasn’t even connected the first two cities in the completely-flat-and-empty Central Valley. It’s unclear if they ever will. The last company they hired to run the project gave up in disgust and moved to Africa because it was “less politically dysfunctional” (this is true!)

Is it possible to become the sort of state/country that can build world-class high speed rail networks, close 80% of prisons, and end visible street homelessness? Yes, obviously, other countries do this, you could become like them somehow. But you don’t do it through ground-level rail policy, prison policy, or homelessness policy directly. You start by becoming a totally different sort of country. I would like for us to be the sort of country that does all of these things, and I hope that my blog posts/donations/votes make this more likely. But I don’t think you can start by planning the gleaming high-tech rail system, before you’ve solved the fundamental problems that make it impossible.

I also don’t think we should wait until we’re a more functional state to solve this problem. But the fact that we have to solve it in spite of dysfunction means we might need to be creative rather than steal the solution Switzerland or somewhere uses.

(I once asked a Swiss person how their streets were so clean, and he answered “everyone here is rich”).

Also, other US cities don’t have long-term mental asylums or anti-camping laws, so how can you use “other US cities manage to do this” as support for those programs?

The fourth broad category of responses was people who thought that, if they just said BE TOUGH many times, God would appreciate their toughness enough to additionally solve all of their totally-non-toughness-related problems.

This is kind of a mean way of putting it. But I’m thinking of people who say things like “We’ll create great wraparound social services with enough beds for everyone…and if people don’t accept them, we’ll send them to prison for a thousand years! I am so tough!”

I admit the prison for a thousand years part is tough, but I’m confused how your toughness is supposed to get you the great social services, when even the non-tough people who focus entirely on social services can’t do this. In general, many of the “BE TOUGH” plans assume so much state capacity, that the state capacity alone would be enough to solve the problem even without the toughness. This is another reason I want to hear people’s plans! When they say “BE TOUGH” they often mean “Assume a magical solution, and have a little bit of toughness on the side”. Then the debate centers so completely on the toughness and whether it’s morally justified that the magic part gets left alone.

“My solution to climate change is to switch all power plants to fusion, make all industries carbon neutral, and replace all cars with superconducting levitating pods - and if anyone complains, I’ll hit them with a lead pipe!”

“Oh no, not the lead pipe, that’s too cruel!”

“Wrong, you’re just a big softie, lead pipes are completely justified in an emergency such as this one!”

The fifth broad category of responses was people who admitted that they didn’t have a plan, but thought they shouldn’t have to - that wasn’t their job. These people are certainly in good company:

See my review of Revolt Of The Public.

See my review of Revolt Of The Public.

As I tried to say in the first part of the post, this is reasonable and sympathetic. But if people keep not listening to your demands, then learning more about the specifics might help you understand why.

There’s a dynamic in gun control debates, where the anti-gun side says “YOU NEED TO BAN THE BAD ASSAULT GUNS, YOU KNOW, THE ONES THAT COMMIT ALL THE SCHOOL SHOOTINGS”. Then Congress wants to look tough, so they ban some poorly-defined set of guns. Then the Supreme Court strikes it down, which Congress could easily have predicted but they were so fixated on looking tough that they didn’t bother double-checking it was constitutional. Then they pass some much weaker bill, and a hobbyist discovers that if you add such-and-such a 3D printed part to a legal gun, it becomes exactly like whatever category of guns they banned. Then someone commits another school shooting, and the anti-gun people come back with “WHY DIDN’T YOU BAN THE BAD ASSAULT GUNS? I THOUGHT WE TOLD YOU TO BE TOUGH! WHY CAN’T ANYONE EVER BE TOUGH ON GUNS?”

I don’t know if the anti-gun people are doing anything wrong here exactly, I just know they’re going to be constantly confused and disappointed, and that anyone else who tries the same strategy will get the same results.

Realistically, my excuse for writing the post was that I read this and this article by Freddie deBoer which assume that there is some clearly-defined thing called “involuntary treatment” and that the kindest option for the mentally ill and everyone else is to lift some kind of law preventing us from delivering it. Even if it’s permissible for the average person to just say “less homeless crime, please”, I feel like at the point where you’re a public intellectual leading the public discussion, you have some responsibility to start talking specifics.

2. Specific Comments And Responses

Shako (blog) writes:

I agree with your point in the post. I’ll add though that a policy that is adjacent to this is be “cruel and draconian” to the subset of homeless who commit anti-social crimes. If we removed the subset of criminals from west coast homelessness the problem would be still visible but far far less concerning to those of us who live among it.

This is where I land too, but I think it’s very hard.

If a homeless person stabs someone, then I think most places (I don’t know if this includes SF), they get prosecuted under general anti-stabbing laws, which the police mostly have enough resources to investigate.

If someone just gets in people’s face a lot and screams and litters, then what? Most of the time, police won’t be around to see this. Most of the time, the victim won’t go through the trouble of pressing charges. If they did, it would be he said, she said. Even if the government puts in the effort to actually try the case, screaming at people and littering is probably a couple-month sentence at most.

Eledex tells a related story in Part 3 here. A group of homeless people took up residence in an empty lot next to his house, harassed him, set things on fire, etc. This is much worse than the average homeless person just bothering tourists, but when he called the police, they never followed up.

I assume if they had tried, the homeless people’s public defender could have said something like “are you sure these homeless people are the same ones who set fire to your stuff?”, Eledex would have said “they’re the homeless people camping on the lot where it happened, but I don’t, like, recognize them or anything”, the public defender would have said “well how do you know those people didn’t leave and some new homeless people came on to the lot?” and everyone would admit they couldn’t prove that.

So the normal criminal system might not be set up to deal with these kinds of issues, which I think is why there’s so much demand for some extreme law that criminalizes the entire concept of being this sort of person. But I do worry that if police don’t have the resources to deal with normal crimes, then whoever is charged with enforcing the new extreme law won’t have enough resources to do it well either - and that any society capable of enforcing the new extreme law would also be capable of solving this through normal policing.

Humphrey Appleby writes:

Can we look at what other places do? What is eg Salt Lake City’s solution? (Possibly, export the homeless to SF). What about Zurich? Singapore? Edinburgh?

The US in general and SF in particular seems to have this problem unusually bad, so one could reasonably look elsewhere for ideas.

I talk a little more about this at https://www.astralcodexten.com/p/book-review-san-fransicko, but I think most places’ solutions are a combination of:

1. Cheaper housing so that more people can afford homes

2. Cheaper housing so that the government has an easier time giving free homes to people who can’t afford their own

3. Homeless shelters

4. Frequent bad weather, forcing the homeless to use the homeless shelters at least sometime, which gets their foot in the door

5. Laws requiring the homeless to use the homeless shelters, which I am much less against when the homeless shelters exist.

Doktor Zum writes:

At one point, there were something like 600,000 Americans in long-term psychiatric institutions, and that was in a less populous America. Start by locking up 600K and then lock up more. Ah, but where do you put them? The 50 states are dotted with the creepy and picturesque ruins of all the old mental asylums–you can’t put them there!

It’s true that the current government (states, local and federal) are totally incapable of building and running a vast network of psychiatric hospitals, but don’t we want government to do things like build nuclear power plants and also lots of housing? If I’m making an argument for cheaper housing and you say “government can’t/won’t ever allow more building,” am I supposed to say that you have won the argument?

Unless we want to embrace full anarcho-capitalism, we have to believe that it is possible to have a government that can do things that it did in the 1950s like (a) apprehend and detain the severely mentally ill, (b) back and create lots of nuclear power plants, and (c) build abundant housing and infrastructure.

People say “we had giant institutions once, so we can do it again”. This is basically true, but with some missed subtlety. The 600,000 people in the old institutions included:

-

Demented old people (eg Alzheimers)

-

People with neurosyphilis (eg you had syphilis for thirty years and it reached your brain). There was a lot of this; I can’t find good numbers, but maybe hundreds of thousands.

-

Down’s syndrome, autism, and other “special needs” adults

-

Inconvenient eccentric relatives who other family members bribed to get classified as psych cases

-

Actual schizophrenics

Around the 1950s, lifespans increased enough that it was worth coming up with separate institutions (eg nursing homes) for demented people. Penicillin cured neurosyphilis. Better prenatal testing decreased Down’s syndrome rates, and better social services let Down’s syndrome patients be treated in the community. It became harder to bribe people to imprison your eccentric relatives. And pharma companies invented antipsychotics to treat schizophrenics. So the effective population for these institutions decreased by an order of magnitude. At the same time, rising health care costs were making them unmaintainably expensive. And yes, civil rights advocates were arguing that they were violations of human rights. So between 1950 and 1980, they were almost all closed down.

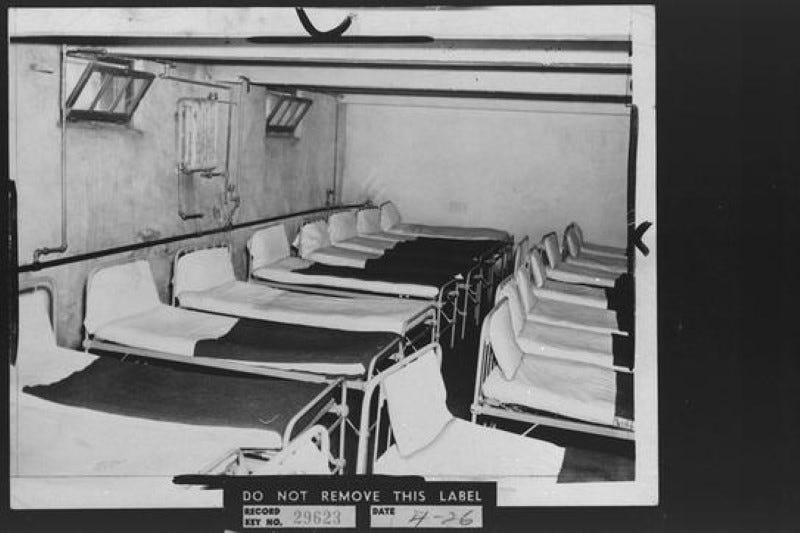

Recreating this system would be tough, both for practical and political reasons. The practical reason is that the cost of everything has increased by at least an order of magnitude since 1950. Partly this is increasing social and governmental dysfunction. Partly it’s because in 1950, it was considered reasonable to build institutions that looked like this:

Even at costs likely 10% of ours, the 1950s couldn’t really afford to keep these institutions around; states were spending about 10% of their total budget just to maintain buildings that looked like the picture above. That segues into the political problem - once there were other options (penicillin, antipsychotics, nursing homes), the public willingness to pay to maintain the institutions collapsed.

On the other hand, when I calculate this out, it doesn’t seem so bad? The average cost of a psychiatric hospital bed is about $300K per year (sanity check: a California prison bed is $130K per year, and the psych hospital needs more medical personnel, so this seems plausible). There are about 8,000 homeless in San Francisco, but assume that most are ordinary people down on their luck, and we only need to institutionalize 2,000. That suggests a cost of $600 million/year using state-of-California numbers, but everything (eg real estate) is more expensive in SF, so round up to $1 billion/year. I don’t know if this counts the amortized cost of building the institution, but let’s assume it does.

San Francisco currently spends about $1 billion/year on homelessness. These institutions would only cover the worst 25% of homeless people, so you’d need maybe another $500 million for the rest, but whatever, same order of magnitude. I think this is more affordable than I expected.

The remaining problems are:

-

Where is this? I don’t think there’s anywhere in SF city limits to put it. I suggest putting it in Marin, to piss off George Lucas’ neighbors. But I don’t know about the legalities of a city using an extraterritorial detention institution.

-

Probably many patients will start doing better once they’re on antipsychotics. Do you release them (at which point they will probably get off antipsychotics?) Or do you awkwardly keep sane people around in your mental institution because you don’t trust them?

-

What are the criteria for committing people to this institution? If it’s “convicted of crime”, we get the problem discussed above: police won’t catch most people. If it’s more like current mental hospital involuntary commitment, remember that this is mostly done on vibes. It’s one thing to use vibes for weeklong commitments, but I definitely saw a lot of basically sane people get committed for stupid reasons. If you’re going to be locking people up for multiple years, you want a better system.

-

If you let people out, what kind of good social services do you have waiting for them? Is this wishful thinking, such that if we were capable of creating social services that good, we would have done it already?

-

$1 billion/year in projected costs, translated into Californian, means $100 trillion quadrillion/year in actual costs.

Of these, I think 3 is the biggest deal. If it’s as hard to commit someone to these institutions as it is to convict them of a crime, then these institutions don’t help much above how much the existence of prison also helps (eg not much). If you invent a new legal maneuver where it’s easier to commit someone than to convict them of a crime, then why do you even need the step where you build the institution? Just invent the legal maneuver and send more people to prison!

I think that maybe the thought is that the institution seems more “humane” than prison, and so people will be more willing to allow low-friction legal maneuvers for confining people there. I think this is cope; not only won’t the institutions be more humane than prisons, but people won’t believe they are and won’t allow the low-friction legal maneuvers.

Drethelin writes:

What if we abolish the DEA and just let anyone buy anti-psychotics over the counter?

This would be the FDA we’re abolishing, but otherwise yes, this is the sort of clever outside-the-box thinking that I appreciate from my commenters.

Antipsychotics are very cheap (some well-regarded drugs like Abilify and Seroquel cost about ~$10 per month of pills). On the other hand, homeless people have very little money. So if you were going to do this, it would make sense for the government to give them away for free.

These drugs have many potentially serious side effects. But it’s not clear how much homeless people’s 5-minute monthly visits with a bored Medicaid doctor does to avert these side effects, over having some kind of pharmacist or advocate or social worker in the free distribution center giving helpful advice.

Like everything, I think this would only help around the edges - the fraction of homeless mentally ill people who drugs can help, who are willing to take the drugs, and who are prevented only by cost and bureaucracy. What percent is that? Low confidence guess 25%.

DZ writes:

I think you’re missing the goal of a short arrest (few days). Part of the problem is the homeless are in areas where society doesn’t want them to be. They’re near city downtowns where tourists spend time or near commercial districts or in otherwise nice parks. If you can arrest them for a few days and keep arresting them until they move somewhere else … the goal is to eventually force them to move to the more acceptable areas vs. least acceptable areas. This is obviously not ideal but in the mean time the city gets more tourism, more office rentals, etc. Europeans ruthlessly arrest homeless people who hang out in the touristy areas. SF doesn’t, yet.

I commented that I was worried that “out of touristy areas” means “into residential areas”. And I feel worse making residents deal with this than tourists, and am less confident that the city cares enough about them to fight back. DZ responded:

Agreed. People don’t want them in the residential areas or suburbs either and for good reason. But my guess is cities can identify certain areas where they would prefer the tents to set up. Something like industrial areas or run down parks. The key is that city officials should be able to use arrests as a strategy to move the tents/homeless concentrations without having to face a million lawsuits.

I don’t know if there are really areas like this, but I welcome learning more from people who know cities better.

SMK writes:

This probably sounds draconian and cruel, too, but in fairness, all these discussions seem to assume that this person is in San Francisco and can never ever leave for some other, more affordable place. I get it – it’s tough leaving home, and maybe they’d be leaving friends. But they wouldn’t be the only people leaving SF over rent prices, and they’d pretty clearly be among the most rational.

So I dislike articles like this when they say things like “the average wait time for a homeless shelter bed is 826 days” or “cheap apartments in SF are $1000 / month.”

I have a friend who was homeless for around a year in another major American city, and he said it was always 100% feasible to get a shelter bed if he wanted one. Indeed, there were several options.

On a different note, I also think that if one were going to go a “cruel and draconian” route, homeless shelters might be able to change policies to better support that and prevent some of the issues you highlight. If it takes 826 days to get a shelter bed, then zero of the typical people you mention who are briefly homeless are getting shelter beds. If all of the people who were homeless for longer were either leaving or in jail, then more of those people probably would get beds. Am I saying this is the policy I favor? No, I agree it’s a hard problem and I’m not sure what the right answer is. But things like this need to be kept in mind, too.

Again, I think it’s helpful to go to the specific policy level. What’s the policy here?

Give homeless people brochures reminding them that other cities exist? I’m sure they know this.

Give homeless cities free mandatory bus trips to those other cities? What prevents the other cities from giving them free mandatory bus trips back? Even if they don’t, what if the homeless prefer being homeless in San Francisco to having a better situation in a cheaper city? A bus from Phoenix to SF is only $60; even a homeless beggar might be able to scrounge up that much money if they’re motivated.

Maybe some plan like making a deal with a big cheap city in Texas to take SF homeless in exchange for money, and as soon as the homeless get off the bus, they’re met by a Texan social worker who gives them a shelter bed and social services? Might help along the edges, but remember that only about half of homeless people want/will accept shelter beds (depending on how good the shelter beds are).

Sergeiwrites:

After checking a bit, let me point out the obvious. What works elsewhere is PATERNALISM.

Once you are in the “clutches of psychiatry”, they don’t let you go. Upon release you are placed into some sort of housing, your appointments are monitored and a social worker will find you and drive you there. You will be given multiple chances to get a job and/or rehab. Your meds will be delivered to you if you cannot pick them up. They remind you to take them. There will be a social safety net so you are never in a situation where you end up on the street unless you really really try to.

In retrospect, it makes sense: people who are not able to take care of themselves for a time because of a fixable mental infirmity are taken care of by the state, until they can. That’s what we do with children already.

I continue to want people to provide details.

“They don’t let you go” - okay, so the person is in a locked facility? Placed in “some kind of housing”? Does the housing have locks on the door, or can they leave? What if they do leave? “Multiple chances to get a job”, oh, great, with whom? How are you enforcing that they take mentally ill people. What happens when the mentally ill people are less good workers than other people they could hire, or have some kind of crisis on the job, as even the best-treated person might once in a while?

Maybe we can charitably fill in the details. Something like:

-

Ban some combination of camping outside and being visibly mentally ill.

-

If arrested, someone will get three months either in a psych facility or a prison with good psychiatric services.

-

When they get out, they’ll be sent to a halfway house with a staff doctor who makes sure they get all of their medications easily and on time, including GLP-1s for opioid addiction.

-

They’re under an Outpatient Commitment Order not to leave the halfway house for a year. During that year, they have to check in every evening, unless they’ve worked something else out.

-

They also need to pass random drug tests once a month.

-

After a year, if things seem to be going well, they’re provided normal subsidized housing.

-

If they can’t stick with this (fail drug tests, leave halfway houses, commit crimes), then they’re considered to have violated probation, and they get a longer jail sentence of several years.

This is an actual plan, of the sort that I wish people would provide but most people never do. It’s not a bad plan. I only see three major concerns.

First, if we could do social services this well, we would have already done it, and we would have much less of a problem. Part of my objection is that people are using “we should be willing to be tough!” as a panacea to cover up the fact that we’re failing even at the non-tough part, as if gaining in toughness would suddenly make us generally more competent.

(for example, right now we don’t even have enough beds for everyone at our crappy homeless shelters. But the halfway houses in this example are much higher-effort than crappy homeless shelters. So after failing to do a cheap easy thing, we would have to succeed at a much harder, more expensive thing).

Second, halfway houses let people leave during the day. Because they’re unpleasant places, most people do leave during the day. That means they’ll be hanging out around parks and public libraries, same as now. Will they be less mentally ill? Maybe, if they stay off drugs and the meds work well. But those are big ifs, and you might find that somewhat-less-mentally-ill dysfunctional-poor-people hanging around parks and libraries is less of an improvement than you thought.

Third, realistically everyone will fail their drug tests and go back to prison, so be ready for that.

Still, if someone credibly promised to make this work, I would probably support it over status quo.

Harry Deucharwrites:

From the your comments, it seems like more shelters solves so much of the problem that it becomes a qualitatively different problem. Why not put that front and center in the main article?

My impression is that in SF:

-

25% of the homeless are in shelters.

-

25% want to be in shelters, but there aren’t enough beds available.

-

25% don’t want to be in shelters, because they’re psychotic and making irrational decisions.

-

25% don’t want to be in shelters, because the shelters have terrible conditions, and they’re so repulsed by them that they would rather take their chances on the street.

I agree that the easiest thing SF could do is make shelters for the 25% who want to be in them but can’t. My understanding is that this is limited by a combination of 1) real estate costs, 2) nobody wants a homeless shelter in their backyard but it has to be somewhere, 3) homeless activists correctly think this would lead to people forcing the homeless into extremely low-quality repulsive shelters, and preempt this by fighting against their very existence.

HemiDemiSemiNamewrites:

How about:

1. single-payer healthcare system

2. free public transport system, patrolled by competent cops so it continues to function and doesn’t become an ersatz homeless shelter, who are themselves overseen by a well functioning internal affairs department

3. voluntary state or national register for “clinically essential drugs administered to at-risk individuals”, which uses fingerprints or iris scanning for identification, has a database which legally cannot be subpoenaed for anything short of child sex crimes or homicide, and which you are placed onto after getting a single prescription for antipsychotics while committed unless you opt out; anyone on the register can get certain meds from a pharmacist without a second prescription unless they’ve been inactive for five years or more

I live in Australia. We have 1., we effectively have 2. for mentally ill homeless people (I think public transport staff are told to let anyone who’s visibly mentally ill but not too distressed through the gates), and I have no idea if 3. already exists or not.

There’s already more or less a single-payer healthcare system for homeless schizophrenics. Poor people get Medicaid, and I am not a legal expert but I think schizophrenia is enough of a disability to qualify people for Medicare too. None of these people pay for their medical care and this isn’t an issue.

In San Francisco, homeless people already get an Access Pass, ie free public transportation on the municipal rail system. I don’t think there’s a similar program for the BART (intercity rail system), probably because other cities don’t want homeless people traveling there. There are definitely lots of homeless people on the BART; I don’t know how this works, but I think they make more begging than they lose from the fares.

The third one is reasonable. My guess is that someone would die from taking the drugs wrong, everyone involved would get sued, and the doctors’ guilds would use that as an excuse to claw back their prescribing power. But if you have enough political capital to fight it off, sure.

3. Comments By People Who Have Relevant Experiences

Daniel Bottgeron helping homeless people get jobs in his native Germany:

I believe you’re looking for this:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sheltered_workshop

Germany has a lot of these. A typical example of such work would be disassembling broken appliances for recycling, or simple crafts like basket weaving. The work isn’t valuable, so these places pay less than minimum wage. In Germany and many countries there are special exceptions to minimum wage laws for such workshops. They have trained staff and good connections to the local health care providers landscape, especially Assisted Housing facilities. I believe these would surely be able to employ psychotic people, at least as long as they take their meds.

And that Wikipedia article says: “In 2021, California banned organizations from paying disabled people less than minimum wage, giving the agencies who employ disabled workers until 2025 to either pay their workers the statewide minimum of $15.50 per hour or shut down.”

Seems to me like that’s a promising point to address, where a specific policy change could help? If these workshops also give work and inclusion and a little money to psychotic people, as long as they do take their meds?

Chris KN on the Norwegian system:

I think California is in a particularly difficult situation, for reasons I outlined in another reply, but I can answer some of your questions for my paternalistic society, Norway, where there are significantly fewer mentally ill homeless people (and not just because they’re doing such a good job).

I don’t want to suggest that Norway has everything figured out. They haven’t. There’s a shortage of resources, and many suboptimal outcomes. But the system does suggest some answers to your questions.

“the person is in a locked facility? Placed in ‘some kind of housing’?”

Yes and yes. Depending on diagnosis. Often both, in turn. You graduate from locked facility to housing. I assume this is common even in California, though, but that it’s a matter of resources?

“can they leave? What if they do leave?”

Yes. As soon as possible (often not soon enough) you get your own apartment, and you’re free to come and go as you wish. Though you don’t get housing unless you’re reasonably safe to allow out into society as an outpatient, and likely to stay. If you leave, with no place to go, and it’s a problem, you’ll probably be identified and helped soon enough, as there’s no big haystack of homeless people for a needle to hide in. Bad things happen, but it’s unusual enough that it seems to spark debate every time.

“Get a job … With whom?” There are protected businesses that exist for this purpose. Bicycle repair shops, fulfillment, simple food prep, light manual labor, etc. Often (not always) businesses that wouldn’t otherwise make sense in a high-cost country like Norway if they were purely profit-driven (e.g. gift-wrapping services) and typically offering jobs that don’t require a lot of customer interaction. Wages and/or other aspects of the business are subsidized, prices are competitive, and customers understand that they may sacrifice some efficiency and sophistication for price and social benefit. These businesses take crises and low productivity in stride (and are rigged to handle it), and no enforcement is necessary.

Because of the scale and nature of the issue in California, the way the culture and economy and politics work, the role of drugs and the criminal justice system, etc, etc, I don’t think California could or should copy that system if they wanted to. And even if they did, it would take a long time, a lot of money, and they’d find it wasn’t perfect.

However, I’m not fond of “it can’t be done” rhetoric, which is very common among experts who know how it’s always been done. (For the same reason, I wanted to ask your clinic director if it wouldn’t be possible to overbook, taking no-shows into account when scheduling, and use good communication and positive incentives, rather than blaming and punishing the patients for the bad finances?)

The older I get, the more often I think “there are no solutions, just tradeoffs”. However, there are usually tradeoffs to be made – especially if you’re willing and able to fiddle with many variables at once, to break out of some local optimum.

HemiDemiSemiName on the Australian system:

I think Sergei was trying to point to a set of better-functioning systems elsewhere, rather than outlining a complete system in itself.

“Some kind of housing” in my local context would mean Community Care Units or Supported Residential Accommodation, thought it might also mean long-term hospitalisation in a Secure Extended Care Unit or getting locked up in I-Can’t-Believe-It’s-Not-Prison.

I think the general pathway for psychotic homeless people is to get sent to an inpatient ward (which is reasonably secure) a few times, then end up in a CCU (which is probably vaguely secure in that you have to ask the nurses to let you out) and enter SRA (which is not at all secure but someone will notice if you disappear) if they seem stable. If they leave, someone will put a small amount of effort into finding them, and then they’ll stay in secure accommodation longer next time. My brother worked night shifts in a SRA house as a disability carer while he was in university and the most traumatic thing that happened was a morbidly obese resident rolling onto and bursting a colostomy bag, so I don’t think they’re terrible places. I am not sure whether they’re cost effective.

California must have inpatient care and forensic mental health. Perhaps it’s missing long-stay residential services and supported accommodation in the middle, or missing the ability to send people to those services, or missing government funding for enough beds? Or more probably I’m misunderstanding the system and patients just aren’t getting sent to those services for legal or procedural reasons.

Merlot (apparently a Canadian psychiatrist?) onlong-acting injectable antipsychotics:

Long acting injectable anti-psychotics are really effective and a huge breakthrough, though not a complete panacea. You need a patient to actually respond to them and tolerate them (not all do), and then there’s some degree of experimenting to figure out how long you can go between doses without losing effectiveness, and there’s variation for different drugs. “Every few months” is something I’ve basically never seen, but all the points above still stand for a once a month injection which is more realistic (at least with the commonly used injectables in Canada). They’re also more expensive than pills which is not the biggest deal, but my understanding is the insurance bureaucracy the US deals with is a pretty big barrier. Missing a dose by a few days is generally fine, but if someone misses for an extended period of time you also have to re-titrate them up to a treatment dose again. There are some additional risks and challenges that come from them being an injectable but they’re relatively minor. It can also be challenging to inject them into the muscle properly on a very fat individual, and they have a side effect of weight gain, but I’d say that becomes an issue in less than 5% of cases. But again, overall they are great, and they increase adherence and decrease rehospitalization.

The thing is you can’t just handwave away how you get the person in the room for the injection every month. Even in jurisdictions like Canada where you don’t have the legal barriers to bringing someone in to get their injection, you need to have available police resources and be able to find and ID the person, which is hit or miss. Using recreational drugs also lowers the effectiveness of the LAIAs (though potentially less than oral meds?), and of course there’s lots of drug induced psychosis in non-schizophrenic homeless people, homeless people with brain injuries, etc. And then you still have a homeless person at the end that requires a bunch of supports, just a less psychotic one that’s potentially easier to house. But they’re a very useful tool, and I’d guess there’s a lot of room to expand their use in the US, even if the impact the public notices is likely to be marginal.

I’ll just add a couple of things. First, I’m not surprised that Merlot hasn’t seen “every few months” because that’s still kind of cutting-edge and might not have made it to Canada, but technically Invega Trinza promises every three months. It’s still very expensive (something like $10,000 per dose), so any health system with resource constraints is probably using older monthly ones that cost a few hundred per dose.

Second, Merlot brings up the issue of titration. Antipsychotics have many side effects, some of which are potentially deadly. Usually if you start experiencing a potentially deadly side effect, you stop the drug. But if you give three months of the drug at once, you are stuck having the side effects for three months, at which point they might kill you. So it’s very important to start by giving the drug as a normal daily pill, then give the injection only after spending a while establishing it has no severe side effects.

There are rules about what to do if people go off the injection and whether you need to use the pills again before re-starting the injection. I haven’t used these injections in a while so I’m not familiar with the details, but I bet they’re annoying.

Theophilus (lawyer, seeblog here) on prosecuting low level offenses:

I think one thing I’d like to expand on is the criminal component.

A lot of “draconian” solutions necessarily require the criminal law (because you get minimal returns out of suing homeless or very poor people). In the United States, this means you’re activating a ludicrously inefficient system to deal with low-level problems. It might be satisfying to a person of a deontological bent that no theft go unpunished, but it’s hardly optimal. A lot of “soft on crime” policies in my jurisdiction come from a place of simply not wanting to bother with the time and expense of punishing an instance of shoplifting.

See, prosecutors make “good deals” that include no jail time as a way to get people to admit their guilt and move the case along. If you don’t make “good deals” and decide to be draconian, people will fight back: they’ll insist on trials for stealing a bag of chips…and nobody actually wants that, because trials have a ton of process. When I get a shoplifting case, I demand security footage (if available). Just getting that to me from the store is often more costly for the store than the stolen bag of chips. If I went to trial on a shoplifting case, I’d probably win unless two witnesses appeared for a whole afternoon: the employee who caught the lifter and the cop who showed up when/if they were called. Losing an employee for an afternoon is already a decent amount of time and expense for a victim, to say nothing of the police/jury/judge/clerk resources that get spent. If the plan is to put someone in jail for 60-120 days for stealing a bag of chips, you’ve turned a case people would normally shrug and admit to into something that is as worth fighting about as a white collar credit card theft. If the plan is to put someone away for 5-10 years for their next instance of loitering because they haven’t learned their lesson the previous 128 times, we’ve turned a low-level misdemeanor into the trial of the century.

Finally and probably most important to your point: the Supreme Court did recently rule that you can technically criminalize homelessness, but actually prosecuting the “crime” of homelessness might be onerous in the future, since there would be numerous active defenses, everything from “there were no shelters available” to the truly preposterous “oh gosh, this was a big misunderstanding, I was walking back to my house and then a dude came out of nowhere and beat me and threw me in a ditch and that’s why i’m in this ditch at 3AM”. Trouble is that even if your defense is truly preposterous, you get a trial…

[…]

I think strictly enforcing the penalties of anti-homelessness laws might be even more difficult than strictly enforcing the penalties of anti-shoplifting laws, simply because the defendants have even less to lose by fighting it out, and might even be more sympathetic to jurors and judges.

In short, my point was that irrespective even of the cost of jail and prison, it’s really expensive and onerous to prosecute people, and if you increase the stakes of prosecution, it gets even more expensive and onerous.

SubstackCommenter2048 (used to work with public defenders),on commitment hearings:

> an overworked public defender who has devoted 0.01 minutes of thought to this case

Hey, something I know a little bit about! I worked briefly with some of these overworked public defenders, doing the legwork of interviewing newly committed psych ward patients to assess their desire for legal representation. Here is what I learned:

1. A lot of these people are pretty shaken up by whatever episode landed them in the hospital and are okay to stick around for a while until they’re back on their psych meds, back on their non-psych meds (a LOT of HIV, hepatitis, diabetes, etc. in this population), and any wounds are stitched up and starting to heal.

2. That’s good, because that’s exactly the same thing most of the doctors want, and they’re willing to release the patients once they’re stabilized.

3. In the minority of cases where a patient wants to leave earlier than that, many are patients whose reasons are not going to go over well at a hearing (e.g., “I need to get out of here before President Terminator Robot finds me”, “I am the Red Dragon of Revelation that is called Satan”). You generally try to talk these people down, but sometimes it goes to a hearing.

4. Many of the rest actually just desperately want to get back on the street, usually because they really love specific drugs that they can’t score on a psych ward, but sometimes, seemingly, because they just love being free from any restrictions on where they can sleep, shit, or fuck, even if it means endangering their health, their sanity, and their lives.

5. For the 3s and 4s, you either go in front of a judge or negotiate with the doctors to get the person released. You do your best to argue that either: a. Even if they’re crazy (that’s the technical term in common use), they do not present a risk to themselves or others, and/or b. Even if they DO present a danger to themselves or others, that’s because they are drunk/high/just an asshole, not because of their mental illness. Sometimes you even believe that the argument is legally sound. On rare occasions, like if you have a really power-hungry or stupid psychiatrist on the ward, you may even find it morally sound. Almost always, the doctors really do have the patients’ best interests as their primary goal, and they have dealt with the legal system long enough to know which battles aren’t worth fighting.

6. This system means that very sick people are in and out of involuntary commitment every few months or even more often. In between, they wreak all sorts of havoc, on their own bodies and minds and on the world and people around them.

7. It’s expensive to house someone on a psych ward; it’s even more expensive to house a seriously mentally ill person in prison; but it’s probably even more expensive than that in terms of social costs to let them wander around for months until the cops pick them up again for assaulting someone, taking a shit in the middle of the floor at a homeless shelter, walking in traffic, etc. Accordingly, I’m very much in favor of re-institutionalization for chronic cases, for some definition of chronic. I recognize that this would have lots of unfortunate consequences. I am convinced that it could be implemented such that it has many fewer unfortunate consequences than our current system.

**CJW (also public defender)also on commitment hearings: **

I worked as a public defender for a few years after law school. In my state we did not represent people at 96 hour commitment hearings. But I can assure you that in the analogous situations where commitment for months was a possible outcome, we would have met with the defendant for at least an hour about just the hearing itself, and likely another hour or two about whatever inciting incident had made them a client before that point. It was not uncommon to have hours worth of conversations with clients who had fixed delusionary beliefs, sphexishly returning to non sequiturs, and/or severe problems with logic and memory.

In the event that a client was absolutely incoherent and unable to communicate about his case or our representation of him, we would review medical report summaries, make notes for questions, and reach out to family members or other contacts, among other strategies. Even on a rushed basis and in circumstances where the ward was entirely non-interactive, I would not have considered anything less than 1-2 hours of review to be adequate representation of somebody in an adversarial hearing the result of which might be commitment for weeks or months or longer.

In my time serving as a GAL, which can similarly impact a person’s liberty interests, the absolute BARE minimum would’ve been something like an elderly patient in skilled nursing following a devastating stroke who could not communicate ideas at all, and who the public administrator or family needed guardianship to have him placed there and the service paid for. In those cases, no matter what I was told, I always still insisted on personally traveling to the facility to verify with my own eyes the person’s condition and attempt to speak with them, and review the doctor’s interrogatories, and find the nurse who works in his wing and ask her questions about him, and even under ideal circumstances this would take at least an hour not counting travel time.

I seriously doubt that ANY attorney is handling serious commitment hearings in the fashion that Markie Post handled bail hearings on TV’s “Night Court”, and if you ever find one that is you should report them.

I have been involved in various commitment hearings, but only at the “few days to few weeks” level. At that level, I got the strong impression that most of the lawyers had never met their clients before the hearing, and had just read some notes and talked to them in the few minutes before the hearing. I’m glad to hear this is either atypical or doesn’t extend to longer-term commitments.

TorontoLLB (works in Toronto mental health)on street living:

I have worked with guardianship and mental health in downtown Toronto for over a decade.

As long as it is an option to live on the street for free, lots of people will choose that option (or default to that option to avoid more difficult choices). Wherever they are permitted, encampment communities grow faster than Austin.

It does not take too long living on the street using drugs and drinking every day for someone to convert themselves into the category of intractably addicted and mentally ill.

I think Scott has started from the “intractably mentally ill” point and done a great job of discussing the tradeoffs and issues with coerced care options. This is where I worked and I agree.

But isn’t the real issue that we have SO MANY MORE homeless and mental health issues and drug addictions than in prior decades?

I think the proper way to evaluate the benefit of making sleeping outside illegal is in how much it slows the current machine converting at risk people into lifelong mental health and addiction patients.

I support zero tolerance for encampments despite the obvious fact that many current mentally ill and vulnerable people will suffer under such a policy. I believe a much larger number of people will be forced to find a path other than setting up a tent and self-medicating.

4. Closing Thoughts

I asked people to present plans. I think these fall into ~3 non-mutually-exculsive categories:

First , enforce existing laws better, such that any homeless person who commits a crime (including public harassment, littering, etc) gets caught and punished. Probably this has to include something like a three-strikes law to prevent a revolving door system. You could also add on some kind of diversion to locked inpatient psychiatric care if this seemed more humane.

I think this is basically a good idea, but I would want to hear more from law enforcement about why it’s so hard to do this now.

Second, make a law against camping on the street. Have good social services so that everyone has an option other than camping on the street, then arrest people who don’t use the social services. If people repeatedly violate the terms of the social services, send them to jail or a locked institution.

I think this is also basically a good idea, but it’s currently tied up in the “have good social services” stage, which - I can’t say this enough - repeating “BE TOUGH BE TOUGH BE TOUGH” won’t help with.

Third, get some kind of long-term mental institutions, train police to notice when people are being crazy on the street, have a legal system where one or two psych evaluations can commit them to the long-term institutions, then keep them at the long-term institutions indefinitely. Maybe combine this with some kind of social services where if they do well at the institution they can graduate to those services later.

I think this is also a potentially helpful idea. As someone who’s seen a lot of entirely sane people get committed to psych institutions for questionable reasons (which was less than a disaster only because the average stay at these institutions was only a few days) I would want to inspect the commitment criteria with a fine-toothed comb. But if you did a good job writing them, you could convince me.

Hopefully this convinces people that I am not some pro-homeless extremist who hates your clean streets and freedom to walk around un-harrassed. I really just want some actual plan that I can be for or against instead of constant exhortations that I’m not BEING TOUGH enough.