Highlights From The Comments On Modern Architecture

Thanks to everyone who commented on Whither Tartaria (currently 1079 comments). Many of you really like modern architecture, and many others of you really hate it. I appreciate most of you being able to accept disagreement on that and move on to the bigger question of why there’s so much more of it now.

The most interesting thing I got from the comments was Chaostician linking to Wikipedia’s page on the Great Male Renunciation - men’s fashion changing from ornate colorful clothing to dark suits. Wikipedia seems pretty convinced that this was because of egalitarianism norms:

The Great Male Renunciation is the historical phenomenon at the end of the 18th century in which Western men stopped using brilliant or refined forms in their dress, which were left to women’s clothing. Coined by psychoanalyst John Flügel in 1930, it is considered a major turning point in the history of clothing in which the men relinquished their claim to adornment and beauty. The Great Renunciation encouraged the establishment of the suit’s monopoly on male dress codes at the beginning of the 19th century.

The Great Male Renunciation began in the mid-18th century, inspired by the ideals of the The Enlightenment; clothing that signaled aristocratic status fell out of style in favor of functional, utilitarian garments. The newfound practicality of men’s clothing also coincided with the articulation of the idea that men were rational and that women were frivolous and emotional.

During the French Revolution, wearing dress associated with the royalist Ancien Régime made the wearer a target for the Jacobins. Working class men of the era, many of whom were revolutionaries, came to be known as sans-culottes because they could not afford silk breeches and wore less expensive pantaloons instead. The term was first used as an insult by French officer Jean-Bernard Gauthier de Murnan but was reclaimed by these men around the time of the Demonstration of 20 June 1792.

In the United States, the movement was associated with American republicanism, with Benjamin Franklin giving up his wig during the revolution, and later the Gold Spoon Oration of 1840 denouncing Martin Van Buren.

The post-Renunciation standards for men’s dress went largely unchallenged in the Western world before the rise of the counterculture and increased informality in the 1960s.

I see no reason to disagree, except that one could argue that there’s a more general trend towards less formal dress - eg from men wearing a suit and hat in public in the 1940s, to today’s t-shirt and shorts, and I’m not sure if that’s also because of egalitarian feelings.

(a few people added that the shift in men’s dress became controversial for a little while after someone on Twitter dramatically attributed it all to a guy named Beau Brummell; more sober historians were very doubtful - see also this really funny thinkpiece on terrible social media historical claims.)

This is interesting because the male fashion change happened around 1800, but the architecture change happened around 1930. Those are different enough times that I need to re-evaluate my theory that the move from ornate to plain across many different artistic fields was all part of the same big transition. If every field changed for a different reason, then some things I ruled out (because they didn’t apply to fashion or poetry or whatever) might need reconsideration as possible explanations for architecture.

For example, cost. Long Disc writes:

For architecture, the headline theory is more or less correct: we are living in an era of a technological regress. We would not be able to build most of these landmarks even if we tried. I live near a nice Victorian bridge https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammersmith_Bridge built in 1880s for around £80k. The standard Bank of England inflation measure gives inflation on a broad basket of about x110 from there to now, so the construction would have cost be around £9m in today money. Now, the bridge is still standing but needs repairs. It is not clear if the repairs can be done for less then £150m. The last time this city built a bridge over the same river, it was a much smaller pedestrian only bridge which cost £18m and then another £5m to repair just a few years later. The last time they tried to build a proper large bridge, they spent £60m on thinking about it, realised it will cost over a £1bn and abandoned the project.

Auros agrees:

Baumol’s Cost Disease and concepts of comparative advantage are critical in here. And you can tell, because actually we are still building, or re-building, a few of these – there was active renovation on Notre Dame (which went horribly wrong with an accidental fire), and Sagrada Familia is actively under construction. But the cost to employ skilled masons to produce that kind of ornamental stonework has gone up drastically relative to the baseline of what laborers broadly earn. It used to be that if you were a lower class person with the aptitude for engineering, “mason” was probably your best career choice. And you could still choose that! But you also could be any of a dozen other flavors of engineer, and many of those choices would carry considerably less risk of bodily harm, plus many of them have the “bits versus atoms” leverage, such that your work can ultimately produce much more marginal revenue per hour of labor. The fact that the kind of person who might decide to become a mason has that kind of life choice available feeds back into what it costs to hire a mason.

If for a given pile of money, we can either build one beautiful art deco skyscraper, or twenty featureless cubes, then the people who have capital to allocate to buy office space are probably going to buy the featureless cubes.

And Max adds:

One 1994 attempt to construct a large building in a classical style (Castello di Amorosa in Napa Valley) cost the owner ~$73m in 2021 dollars, and the quality of the workmanship still doesn’t come close to what you see in the best examples of the 1800s.

Remember, the Baumol effect happens when new technology makes some industries more productive. Since the high-tech industries are so lucrative, wages go up. Then low-tech industries have to raise their wages so that their workers don’t all desert them for the high-tech industries. But since low-tech industries aren’t improving their productivity, they just because more expensive, full stop.

If stonemasonry is a low-tech industry, and new high-tech industries are arising all around it, stonemason wages could get prohibitively high (compared to everything else) until nobody wants to hire them anymore. This would create pressure for architectural styles that require as little masonry (or, generalized, human labor) as possible.

This has gotten me thinking about furniture.

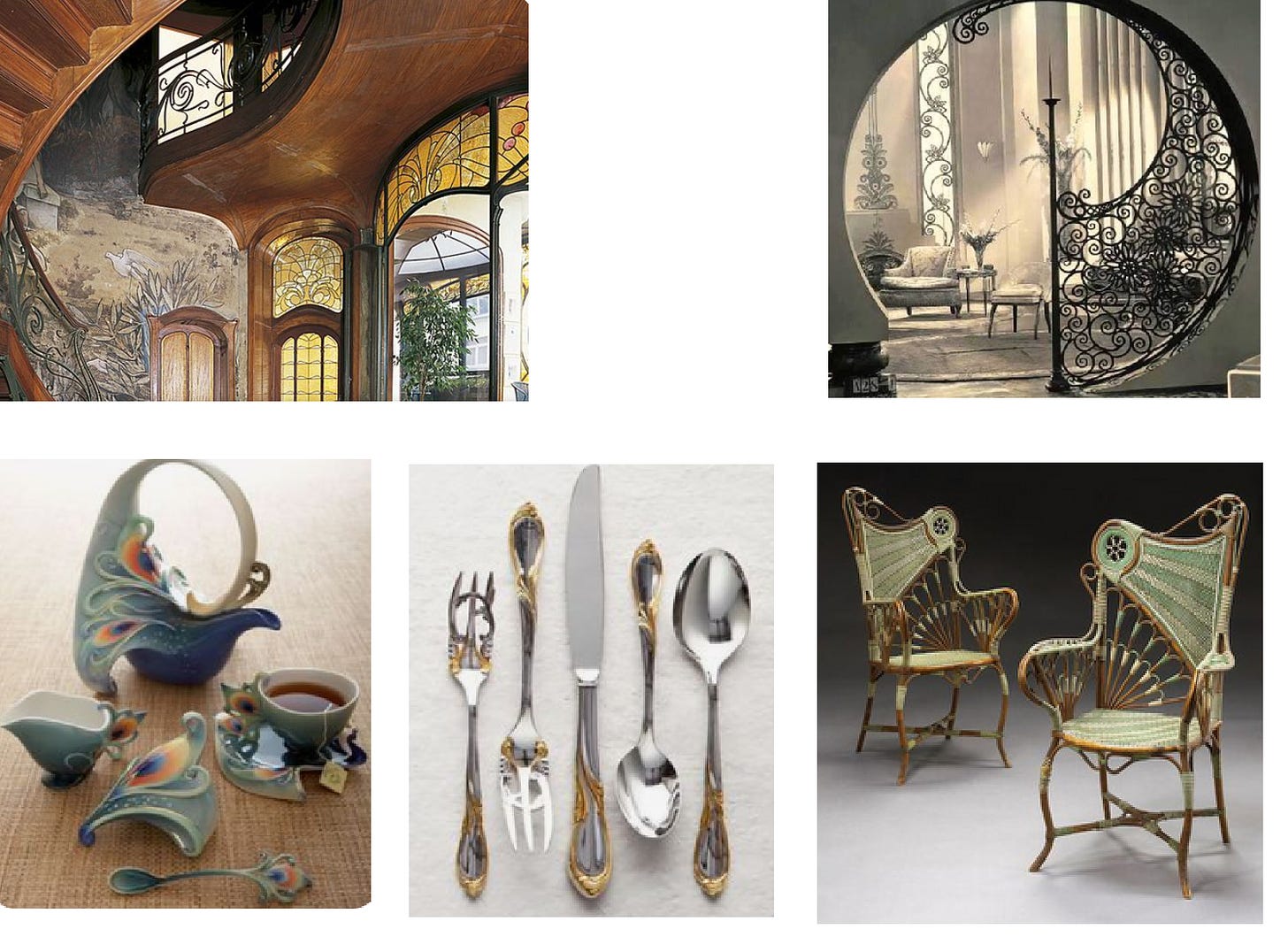

I got a new place recently and have been looking for furnishings. Sometimes I look at people’s furniture Pinterests. If Pinterest is any kind of representative window into the soul of the modern furniture-enthusiast, people really like Art Nouveau. Typical pictures that people pin will look like this:

As far as I can tell, you can’t buy any of these anywhere - they’re a combination of antiques and concept pieces. The people who pin these and pine after these end up getting minimalist Scandinavian furniture with names like UJLIBLÖK, just like everyone else.

Anything that even comes close to the above costs high four to five digits. I don’t know if this is because it’s antique, because it requires more labor, or both.

But this isn’t an antique, and it doesn’t,uh, seem to be going for the high-end classy market, yet it still costs $2399. Maybe this is because it actually costs a lot to produce?

But this isn’t an antique, and it doesn’t,uh, seem to be going for the high-end classy market, yet it still costs $2399. Maybe this is because it actually costs a lot to produce?

I’m harping on furniture because it avoids a lot of the complicating factors in architecture. There isn’t some vague collection of “elites” making our furniture decisions. It’s a pretty free market! There are lots of normal middle-class people spending big chunks of money on furniture, lots of them really really like the old stuff, and the old stuff is still either unavailable or unaffordable. It seems like it used to be affordable - it wasn’t just kings and dukes who had the old Art Nouveau stuff - but for some reason that’s changed. I think Baumol effects offer a tidy explanation here, and if we use them to explain furniture, then they start looking really attractive for architecture.

I want this one to be true, because it exonerates our civilization. If we could make things like the Art Nouveau furniture above, or the Taj Mahal, relatively cheaply and easily, then the question of why we aren’t doing that demands an answer. If it’s just a quirk of basic economics, then our civilization is fine, and maybe we can hope that stoneworking technology advances to the point where we can do this kind of thing again cheaply.

My big remaining objection is: if this is true, why isn’t it obvious? How come we don’t have architects saying “Of course I’d like to build something ornate, but it costs too much”? How come we don’t have rich people (and the occasional cash-flush government working on a monument that it really cares about) saying “screw the price, I really want this one thing to look nice”? I feel like I’m doing some kind of weird archaeology here to try to discover why this happens, whereas every single person in architecture and construction and so on should know whether or not this is true.

Even if Baumol is part of the explanation, there must be some other part, a kind of Stockholm Sydrome style explanation for why, after it became hard to build ornate things, we went all sour grapes and decided that actually, ornateness is bad. I don’t want to speculate further here, because the responsible thing to do would be to actually figure out the economics here before moving on to the consequences of the economics; I have a friend who might work on that and I’m going to hold off until they’re done.

Jacob writes:

Any theory of this change has to account for buildings like this one: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sheikh_Zayed_Mosque

And this one: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swaminarayan_Akshardham_(New_Delhi)

The things that these two buildings have in common are:

- Built by very low-wage South Asian laborers (maybe the economic explanations really do matter?)

- Religious and nationalist goals (thus designed to express/elicit popular not elite sentiments?)

I’m sure there are other examples as well, but these were the first two that came to mind. Both are very very impressive IRL! In particular, the pietra dura work on the Sheikh Zayed mosque is very similar in both style and quality to that of the Taj Mahal.

Related, from aesthetics tweeter Xirong:

Metadoxy @Xirong7Essentially completely ignored around the world , Thai architects are some of the last to continue to innovate On traditional architecture styles

Metadoxy @Xirong7Essentially completely ignored around the world , Thai architects are some of the last to continue to innovate On traditional architecture styles

[9:28 PM ∙ Aug 24, 2021

[9:28 PM ∙ Aug 24, 2021

4,177Likes761Retweets](https://twitter.com/Xirong7/status/1430281000429531136)

Thailand seems to have a daily minimum wage of $10, which probably works out to a little over a dollar an hour, which is probably close to what the West was paying people back when it had Art Nouveau and such. I don’t know if this is a coincidence.

But Kaleberg argues the exact opposite point:

Architectural ornament is much cheaper than it used to be, so it is less important. There was a big boom in statues and curlicues in the late 19th century and into the early 20th, but a lot of it was about new techniques for sculpting forms in stone or metal. All those charming buildings in NYC’s Chelsea were the result of the falling cost of cast iron fixings. Sure, adorn your office or apartment building with colonnades and six dozen statues of Audrey Munsen and see if you impress anyone.

BronxZooCobra agrees:

The other issue I had explained to me involves the Queen Anne style Victorian. A generation before that kind of detail would have been ruinously expensive. But with new technology they were able to mass produce all those wooden details. For a while poorer (but obviously not poor) people used that to build houses that were above their station. And then the rich had to go in the opposite direction and go much simpler.

A Queen Anne style house (source)

A Queen Anne style house (source)

Okay, this ought to be an empirical question. Does architectural ornament cost more or less than it used to? If somebody does a deep dive into this, I will absolutely link them. If you think you could do exceptionally good research in exchange for money, please contact me.

William Cunningham frames the political angle a little differently:

There are some interesting side details to this. 1) civil engineers hate the fancy parts of new architecture frequently. Turns out that if something looks impossible, it’s often at least very hard. 2) building code, building science, even availability of materials and construction crews familiar with particular techniques are often huge constraints on this sort of thing. LEED gold certification is a big deal for any entity capable of affording a classical style massive building, and in many ways it actively insists on not doing the things that make classical buildings last. Watch just about anything by Joe Lstiburek where he discusses wall and window efficiency and issues, and marvel at how poorly we build buildings these days. 3) good luck getting the permits in a typical city to build something like the Art Deco Detroit Train Station — it’s massively too big for its neighborhood these days and all the “in character for the area” crap isn’t going to be easy for the cool old giant buildings. I don’t have great evidence that this is the case, but I have a feeling that selling a small group of “elite” people like a planning board on the exciting new thing is easier than an Art Deco style fancy building. 4) cost to do a lot of the old style things has skyrocketed, so going cheap or justifying new expensive on environmental grounds is the new way of the world.

Yeep says:

Part of the issue is building something traditional that meets modern standards for things like insulation is prohibitively expensive. Most of those Barrett homes are still modern timber frame with a facade of stone or brick on the outside, the more offensive ones don’t even put the stone somewhere that makes sense from a structural view, it’s obviously just a decorative layer.

There’s currently a new house being built near where I live entirely out of stone, complete with masons and chisels on site, presumably because it’s in a conservation area and had to match the surrounding properties. But it looks like they’re building a traditional stone shell then lining it with what is effectively an entire modern house on the inside, which is going to be almost as expensive as building two houses.

And one of the responses is by Jim, who is finally (hallelujah!) a real architect. He writes:

I’m a professional architect, albeit one of the minority who does traditional design work. Will try to answer a few of your questions here and below.

> >But if the changes wrought by these thinkers are so unpopular, why haven’t market forces simply swept them away? People have agency over which art they buy, which galleries they visit and over which houses they buy. In the UK, where I’m based, basic market logic supports your intuitions: old houses command a premium. But that preference hasn’t been carried through into the housing projects that are built.

Because almost all of the architects are modernists, and you need to hire an architect to get a new building built. The complexity of design and construction has increased enormously in the past century, in part because of new technologies and in part because of regulation. The design professionals have the licenses and expertise that you need to navigate the maze, which puts you at their mercy. They can throw you a few bones by making vague references to your preferred aesthetic, but mostly they’ll do what they’ve been taught to do and like.

And since modernism is all they know, even their sincere attempts to do traditional design work tends to generate kitsch. That goes to your comment about Poundbury below.

This goes back to a point I revisit a lot: capitalism is still not capitalist enough. No matter how hard you try to get everything based on money and market forces, it’s still controlled by kind of elite taste and sense of “wouldn’t want to make waves”. We need double-capitalism - no, fifty capitalisms!

Jim continues:

The funny thing is that, in my experience of actually dealing with them, NIMBYs are motivated in part by the sheer ugliness of so much new development. The YIMBYs hate on the historical commissions and their stringent design reviews, but it never occurs to them that if new developments looked more like the historic districts they degrade, people might actually support them more.

Note that the preservation movement followed close on the heels of widespread modernist building. It’s quite possible that modernist architecture has had an enormous, though indirect, negative economic impact on middle class Americans by driving land use restrictions that make housing more expensive.

Oh, thank goodness - finally a way to turn this into an EA cause!

I also got some comments from a professional sociologist, Cicada Meth Orgy Fungus (look, people on Twitter have weird names sometimes). He writes:

Cicada Meth Orgy Fungus @RogueWPAfwiw, the consensus in sociology of culture is what @slatestarcodex discusses under the headings “Signaling Wealth To Signaling Taste” (Bourdieu’s Distinction) and “Split Between Art And Mass Culture” (a bunch of recent stuff coming out of econ soc)

Cicada Meth Orgy Fungus @RogueWPAfwiw, the consensus in sociology of culture is what @slatestarcodex discusses under the headings “Signaling Wealth To Signaling Taste” (Bourdieu’s Distinction) and “Split Between Art And Mass Culture” (a bunch of recent stuff coming out of econ soc)  astralcodexten.substack.comWhither Tartaria?…11:10 PM ∙ Sep 23, 2021

astralcodexten.substack.comWhither Tartaria?…11:10 PM ∙ Sep 23, 2021

…with the recent stuff being this and this.

Some people mention Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate , which apparently has a chapter on this. It contrasts a traditional idea that architecture needs to appeal to some innate sense of beauty vs. a modern idea that there are no innate senses and so it can be whatever is easiest or more politically convenient. Fluffy Buffalo writes:

I think Steven Pinker had some good insights on that issue in “The Blank Slate”. If I remember the argument correctly: modernist architecture/ city planning/ art came into fashion as the conviction spread that there was no such thing as a “human nature” - that, in fact, human tastes and human society were nearly totally malleable, and shaped by their surroundings.

That can take different flavors: the proactive approach is, if you thought that the olden ways were bad and needed to be changed (and after centuries of monarchy, after the excesses of the industrial revolution, and after World War I, there was good reason to believe that), getting rid of the art and architecture of these periods and replacing them with something radically different was a good first step toward molding a new society. This was explicit in communist countries, maybe less so in democratic ones.

The lazy approach is, if people don’t have innate preferences, you don’t have to worry about making buildings aesthetically pleasing, providing green spaces etc. You can build stuff as cheap and as functional as you can make it, and after a generation no one will miss the pretty old houses and cozy parks. That was probably the thinking behind a lot of post-war planning in Europe - partly out of necessity, because the old stuff was lying in ruins, and rebuilding it close to the original would have been a luxury that would have been hard to justify. The same approach is also present in US housing projects from the 70s onward. And in office buildings around the world, for that matter :-/

Did this reshaping work? Yes and no - we ended up in a place where people still miss the old elaborate styles (because, IMO, they did tap into universal human aesthetic preferences) and pay good money to travel to see the old masterpieces of art and architecture, but where it would still feel weird and anachronistic to just bring them back. It may be time to find a new twist - a new way to please those preferences that doesn’t feel 100% rehashed old-school. In architecture, I think new technologies should help a lot - with 3D painters, CNC machines, robots, CAD and AI, it shouldn’t be too hard to come up with a way to produce eye-pleasing ornaments , murals and building shapes at a reasonable price. But no one is doing it, because the current crop of architects can apparently only think in steel, concrete and glass.

Michael Watts quotes Pinker at more length:

Steven Pinker devoted a chapter (“The Arts”) of The Blank Slate to this question. He comes down pretty strongly in support of the idea that the elites do this stuff because people don’t like it. (As presented above, “Maybe elites are specifically trying to signal not being commoners, by choosing the opposite of commoners’ aesthetic preferences?”)

Modernism certainly proceeded as if human nature had changed. All the tricks that artists had used for millennia to please the human palate were cast aside. In painting, realistic depictions gave way to freakish distortions of shape and color and then to abstract grids, shapes, dribbles, splashes, and, in the $200,000 painting featured in the recent comedy Art, a blank white canvas. In literature, omniscient narration, structured plots, the orderly introduction of characters, and general readability were replaced by a stream of consciousness, events presented out of order, baffling characters and causal sequences, subjective and disjointed narration, and difficult prose. In poetry, the use of rhyme, meter, verse structure, and clarity were frequently abandoned. In music, conventional rhythm and melody were set aside in favor of atonal, serial, dissonant, and twelve-tone compositions. In architecture, ornamentation, human scale, garden space, and traditional craftsmanship went out the window (or would have if the windows could have been opened), and buildings were “machines for living” made of industrial materials in boxy shapes.

Why did the artistic elite spearhead a movement that called for such masochism? In part it was touted as a reaction to the complacency of the Victorian era and to the naive bourgeois belief in certain knowledge, inevitable progress, and the justice of the social order. Weird and disturbing art was supposed to remind people that the world was a weird and disturbing place.

But modernism wanted to do more than just afflict the comfortable. Its glorification of pure form and its disdain for easy beauty and bourgeois pleasure had an explicit rationale and a political and spiritual agenda.

Modernist and postmodernist critics fail to acknowledge another feature of human nature that drives the arts: the hunger for status, especially their own hunger for status.

The problem is that whenever people seek rare things, entrepreneurs make them less rare, and whenever a dazzling performance is imitated, it can become commonplace. The result is the perennial turnover of styles in the arts.

In twentieth-century art, the search for the new thing became desperate because of the economies of mass production and the affluence of the middle class. As cameras, art reproductions, radios, records, magazines, movies, and paperbacks became affordable, ordinary people could buy art by the carload. It is hard to distinguish oneself as a good artist or discerning connoisseur if people are up to their ears in the stuff, much of it of reasonable artistic merit. The problem for artists is not that popular culture is so bad but that it is so good, at least some of the time. Art could no longer confer prestige by the rarity or excellence of the works themselves, so it had to confer it by the rarity of the powers of appreciation.

[O]nly a special elite of initiates could get the point of the new workds of art. And with beautiful things spewing out of printing presses and record plants, distinctive works need not be beautiful. Indeed, they had better not be, because now any schmo could have beautiful things.

In his 1913 book Art , the critic Clive Bell [] argued that beauty had no place in good art because it was rooted in crass experiences.

Thirty-five years later, the abstract painter Barnett Newman approvingly declared that the impulse of modern art was “the desire to destroy beauty”.

In the year 2000, the composer Stefania de Kenessey puckishly announced a new “movement” in the arts, Derrière Guard, which celebrates beauty, technique, and narrative. If that sounds too innocuous to count as a movement, consider the response of the director of the Whitney, the shrine of the dismembered-torso establishment, who called the members of the movement “a bunch of crypto-Nazi conservative bullshitters.”

I mentioned that last anecdote to the art teacher in my high school, and was surprised to get a fairly enthusiastic response to the effect that yes, there is a raging controversy over whether art should be beautiful, and if not, whether beautiful art should even be allowed. She directed me to a recent story, clipped and posted to her bulletin board, about a city which had arranged for a public art project, seen the proposal somehow come in as a larger-than-life statue of Poseidon in the form of a merman holding the reins of five orcas, canceled the project because that’s just not the sort of thing we do, and run into the absolutely unprecedented problem of massive public support for the public art project they wanted to cancel.

Other people focus more on the idea of deliberate ugliness because our civilization doesn’t deserve beautiful things. Aka writes:

So so much postwar art is exactly about this, clearly and explicitly. please read some midcentury criticism or like any art history or theory. I dare you to read this: https://www.amazon.com/Art-Culture-Critical-Clement-Greenberg/dp/0807066818

And Pachyderminator:

Theodore Adorno famously said “It is barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz.”

Some people were very insistent about this, saying that I was stupid for not having read the primary sources where post-WWII builders explain that this is exactly what they are doing. I admit that my claim in the original post that I hadn’t heard people say this before had more to do with my own ignorance than with what other people had said, and I will try to read those sources, but I think these people’s strident tone is a bit misplaced. Even granting that many people said that, there still seems to be a mystery here. Did Google think about the horrors of WWII before deciding to build a kind of ugly headquarters? Did some random 1990s suburb think about the horrors of WWII before deciding to build a kind of ugly City Hall?

Usually there is some group of people with some silly idea, like “let’s only build ugly things to remind ourselves of the horrors of WWII”, and they make like five things, and then the market gives ordinary people what they want, which is pretty things (at least for some watered-down mass market definition of “pretty”). If someone said “let’s only eat bad food from now on to remember 9-11”, it would never work. Heck, people won’t eat slightly-worse-tasting food to avoid diabetes and save their own lives. If some group of architects actually coordinated the entire world into only building ugly buildings for 70 years to in order to make an important moral point, this would be one of the most impressive acts of coordination in the history of the world. We should find these same architects and ask them to coordinate us into only building environmentally-sound buildings in order to prevent climate change, or whatever.

I guess I’m willing to accept “some people did this originally, and those people were cool, and then that became the cool thing, and then we ended up in a vicious cycle where everyone has to pretend to like it”, but if that were true it would still be pretty astonishing.

Also, are we still doing this? Because people like Frank Gehry are making stuff like this:

…which doesn’t exactly scream “penitence” or “silent contemplation of the evil within us all”.

Phil Getz goes…a lot deeper than I was expecting:

I’ve been exploring the question you’re asking for the past several years. I haven’t got a well-organized answer yet, nor time today to say much. But this isn’t an isolated phenomenon. Rather, it’s a pattern that has repeated throughout history and around the world, one of naturalist art executed with great skill being deliberately replaced with highly abstract art not requiring as much skill.

- The cave paintings of Chauvet Cave in France ca 30,000 BP (before present) are more natural and technically much more sophisticated than any cave or rock paintings found after 20,000 BP (some of which are quite abstract and stylized).

- The stone “goddess” idols of Europe circa 6000 BP were more realistic than their artistic descendants, the highly abstract, smooth, angular stone “idols” of the Cyclades, ca. 5000 BP, which were strong influences on modern art.

- Minoan and Mycenaean art (circa 2000 BCE) were both much more naturalistic and sophisticated than the highly abstract Greek art of the Geometric and Archaic periods.

- Ancient Egypt produced extremely skilled naturalistic art, and very stylized, abstract, and seemingly less skillful art at the same time. Check out the art of the pharaoh Akhenaten, who briefly introduced very naturalistic, realistic art, and was erased from history after his death. Note that most Egyptian wall paintings are Cubist.

- The representational art of Western Europe, starting with Constantine, and throughout the Middle Ages (with the exception of the Frankish court and some Byzantine art), up until nearly 1300 AD, seems to have been very deliberately bad, and in many times and places it was banned entirely. This was probably due to Christianity and Islam both having a horror of the misleading power of representational art (which fear came straight out of Plato). Note much medieval art was also Cubist.

- 19th century African art, which is what everyone today thinks of as “African art”, is nearly all highly abstract and anti-naturalistic (and was also a big influence on modern art). Yet the very few pieces of pre-colonial African art (pre-1500 CE) which we have are more naturalistic and technically sophisticated, including a few (from present-day Nigeria) that were more skillfully made than their European contemporaries. I’ve even seen a series of statues made in Benin, from IIRC 1400 to 1900 AD, which show the gradual loss of realism and heightening abstraction.

Don’t think of this as “progress”. We also see change in the opposite direction; e.g., the gradual naturalization of Greek art from the Archaic, through the Classical, and into the Hellenistic era. Art around the world has always cycled between the poles of naturalistic realism and abstract spiritualism. The former tends to appear in times of wealth, safety, sea trade, and intellectual freedom (e.g., Athens, Venice, Renaissance Italy, the Dutch Masters, Elizabethan England); the latter, in times of great crisis. I think this is because abstract art is, seemingly without exception, more spiritual in its motivation.

These two opposing types of art are based on two general opposing philosophies, one which takes the physical world as real versus one which takes the transcendent as real. Many artistic features of each recur consistently. For instance, abstract art is often linear, with clear black borders between solid (unshaded, unmixed) primary colors, cubist in perspective, & uses size and distance to denote spirituo-political rather than physical truths.

The underlying opposition is not so much stylistic, as about the “purpose” of art. “Spiritual” art comes from the point of view that one already possesses absolute Truth, and the purpose of art is only to indoctrinate (as in Plato). Nazi and Stalinist art both used “naturalistic” representational techniques, yet were spiritual in nature: they used art for the same propagandistic purposes as religions do; they always presented images of either the ideal or the demonic; they are generally images of power. Art that is naturalistic “in nature”, by contrast, is made by people who are studying nature and trying to understand it, as opposed to people who scorn messy, “imperfect” nature in favor of their beautiful abstract “Truth”. Naturalists don’t see everything in terms of propaganda, power, and conflict.

The rise of modern art is well-documented. The motivation for its abstraction derived originally from Plato–modern art is supposed to be the artist-as-prophet providing humanity with a more-direct vision of Plato’s transcendent forms; the argument for why representational art is bad comes straight from Plato’s Meno. (Though many of the early modern artists got their Plato indirectly, through Christianity or Hegel; and Romanticism and the decadents were also major influences.) Those other periods of abstract art I just mentioned which were just then being discovered were also influential, as was medieval art.

But analysis of the rise of modern art has been hindered by the fact that it was an ideological movement which still controls academia and Western art institutions, and it has always been in that movement’s interests to revise the past in order to blame its failures on its enemies. For instance, you’ll commonly read that modern art began as a response to the horrors of WW1. The truth is quite the opposite: proto-modern artists were demanding a great war from about 1906, and got quite psyched up about WW1 (see eg Ezra Pound’s BLAST). They believed Western civilization was systemically corrupt and needed to be utterly destroyed before they could create “true Art”. (They used phrases like “a clean sweep” and “a great burning”.) Albert Gleizes, one of the founders of Cubism, hoped for the complete destruction of cities and a return to a more pastoral, spiritual, community-oriented medieval lifestyle. The artists now paraded as “modern” to give the illusion that modern art was some sort of peace protest movement–e.g., Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen–weren’t modernists at all; just read their poems. Not a single modernist technique among them.

Spencer Maynes writes:

One of the largest causes, as stated by Frank Lloyd Wright, Ezra Pound, Monet and other important early modernists themselves was the collision with minimalist Japanese culture/Zen philosophy in the late 1800’s. Frank Lloyd Wright and other early modernist architects were heavily indebted to Japanese architecture (see https://franklloydwright.org/frank-lloyd-wright-and-japan/). Minimalist poetry descended from the haiku (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_a_Station_of_the_Metro).

Impressionist art was modelled after wood block prints (https://blog.artsper.com/en/a-closer-look/influence-of-japanese-art-on-western-artists/).

So minimalist modernism in the West may actually owe more to curiosity about Japan following the Meiji Restoration than to internal factors. As the rare person who actually enjoys (some) modernist buildings and art, I think this cultural appropriation was probably a good thing.

The ugliest buildings to me nowadays are probably McMansions. They try to imitate traditional 19th century or earlier building styles, but fail heavily, partially because Baumol’s cost disease means less easy access to the heavy manual labor those styles required.

I might be the only person in the world who likes McMansions. They just look like nice, pleasant buildings made by people who want to vaguely enjoy the place where they live. Probably the least offensive thing people are making these days.

Left: the dreaded McMansion, widely reviled as an eyesore ruining the built environment. Right: a house designed by Valerio Ogliati, an a world-famous architect profiled by the New York Times last month.

Left: the dreaded McMansion, widely reviled as an eyesore ruining the built environment. Right: a house designed by Valerio Ogliati, an a world-famous architect profiled by the New York Times last month.

Michael Watts brings up an aspect of signaling I’d forgotten about:

There is something to this point:

This only works if making beautiful things is expensive. For example, the clothing of the Kanxi Emperor (first picture on left) required servants to create the intricate patterns, dyes that had to be harvested from finicky insects and rare plants, etc. Displaying your ornate dyed objects let everyone know you were rich. With the invention of sewing machines, industrial dyes, rhinestones, etc, even poor people could dress like the Kangxi Emperor.

[But] it is overstated. This problem was encountered by pretty much every traditional society, and they almost all implemented the obvious answer of sumptuary laws. Wearing yellow clothing in China could get you in serious trouble. Wearing clothes with dragons on them would get you in serious trouble. Feudal Ireland had a careful system in which your social status determined the number of different colors you were permitted to wear simultaneously. Etc. etc. etc.

And while imperial costumes are popular in modern China, and lots of people have them or rent them, they are, predictably, cheap imitations. A true imperial robe would be cheaper now than it was at the time, but it wouldn’t exactly be cheap today.

Fern writes:

From my own reading the best theory I’ve seen is that we lost the language of beauty. It’s a bit like trying to revive Latin. For any but the most genius artists to make beautiful things, you need centuries to build up a corpus of techniques, habits, useful misunderstandings, etc, so to raise the general level.

This level itself seems to be many things. Firstly technical, we literally don’t have enough stone carvers, people don’t understand the value of it, and economics compounds things in losing economies of scale.

Secondly cultural, surely you need a period of time for the taste of the audience to be both discovered and formed by art, and this in a coherent cultural context. Globalisation might kill art by removing context, as if you were to paint a painting without a canvas.

Thirdly there’s freedom to follow patterns that lead towards beauty, paradoxically because we preach too much freedom. I personally suspect our lapse from making beautiful things has sewed ways of thinking that prevent any but the most extreme free thinkers from reconstituting the foundations for beauty, which is not the same skillset as an artist. I’m personally interested in rediscovering how buildings were ornamented, and managed to read an entire book that said nothing useful at all. A good example of a pattern in ornament that we’d struggle with today is that ornament isn’t meant to overwhelm, it’s decoration, it should develop and harmonise with building form. Today the artist is told to show their vision, but this harms them if they leave the canvas. Their idea of freedom prevents them from appreciating the nature of their restraints, and the new freedom that creates.

So I’m personally unsurprised that we’re struggling to make beauty today, though it’s a mystery how we got here in the first place. My best idea is high modernist mass construction undermined the economics of art long enough to break continuity of knowledge between generations, but his isn’t a sufficient theory.

Hard disagree.

Here are some of the art installations from Burning Man:

| [](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F25262ff7-bf01-4e2c-b7c6-13d53a86392a_980x653.jpeg) |

(source)

(source)

I will leave it up to you whether this is “true art” or “beautiful” or any of those vague terms. But nonprofessionals with limited budgets are making things very different from the usual modernist stuff. If we wanted our public art to look very different, we could do it tomorrow.

David, The Economic Model writes:

So, is it just me or is the Tartaria conspiracy theory… blatantly obviously correct? Like, our modern society has all the trappings of that sort of “twilight of the gods” fiction. We have technology which we still use despite being unable to produce it (nuclear power, skyscrapers, space travel), a culture of pessimism and trying to hold on to what we have over producing anything new, a decadent and onanistic upper class, a drugged-into-complacency lower class. Like, there’s nuttiness which I don’t accept, but this seems so abundantly obviously true-in-substance that I feel like it just barely counts as a “conspiracy theory”. Just scratch out the references to “Tartarian Empire” and replace it with “Interwar America” and it seems like a fairly accurate description of history.

I want to make it clear that even though I used the Tartarian conspiracy theory as a frame story for my (hopefully) reasonable speculations about art, the actual conspiracy theory is bonkers and not “basically correct” in any sense. I haven’t explored all the nooks and crannies, but I know part of it is that Tartaria was destroyed by a “Great Mud Flood” which explains why so many buildings have basements with bricked-up windows (I have never seen this - is it true? If so, what is the explanation?) I have been looking at the preview of this book, which appears to assert that (among other things) that Neil Armstrong and Yuri Gagarin were the same person, but scientists have covered this up. It also includes the truly excellent sentence “Researchers concluded that history and science are probably a set of lies”.

So no, this conspiracy isn’t just shorthand for “there’s been some technological regress over the past century.”

Summer writes:

i think you might be ignoring the role of novelty here. like, if youre the sort of person who is very interested in a given art form (say, designing buildings), youre gonna study them a lot, and then get bored of the types of buildings that already exist, and want to see and create new weird buildings. i mean, i agree that its weird and maybe bad that weird artsy buildings have become a thing for government buildings, but i dont think its surprising that the architecture world is interested in buildings that the average person isnt, because the average person doesnt want an interesting or novel building, they just want a good building (a reasonable desire!). its like stravinsky’s atonal music. it sounds worse, like, aesthetically, but its very clearly weird and novel, and if you think about music all the time, (maybe) you want that..

i think the most famous and esteemed architecture of the last 50 years is extremely diverse. frank gehry vs frank lloyd wright vs moshe safdie vs zaha hadid look like they come from different planets.

In case you don’t immediately recognize all those names, here’s one top building from each:

Tom P adds:

In the 1800s, an elite person had probably only seen a few dozen magnificent buildings in their life. Today, every architect has seen (pictures of) nearly every magnificent building on Earth. So as the pool of comparable buildings has exponentially expanded (from dozens to thousands), novelty has become much more prized.

Daniel makes a similar point about music:

Prestige within a creative field is so tightly bound with novelty that it’s pretty much inevitable that ambitious new works must abandon older forms, even when many of the artists and elites may prefer them.

Personally, I think the greatest music ever written was from the Romantic era, specifically Beethoven’s symphonies. Plenty of music critics (classical ones, at least) would agree. And yet, nobody writes in that style anymore, and nobody seems to think anybody should be writing in that style. Romantic music is done, like it or not (I don’t).

And then it devolves into complicated discussions by people who know music theory a lot more than I do, for example Heinrich:

I agree with all this. I think where it gets challenging is where the most parsimonious ways of doing something, given the constraints of tonality and the other rules of music, have already been “taken”, so to speak. I think this may be true of fugal counterpoint, which seems to want to tend stylistically towards a kind of robust baroque language a la Bach and Handel, and no-one since the mid C18th has really been able to do it particularly differently. So do we accept that that’s basically how fugues sound, or do we resolve not to write fugues? Not sure

I think my objection to this is that modern buildings look alike to me on most axes. I understand that one is a pile of weirdly-shaped concrete blocks and another is a pile of differently-weirdly-shaped concrete blocks, and that in some sense those must be totally different architectural problems. But there’s no modern building that looks as different from any other modern building as either looks from a cathedral - let alone more different than a cathedral looks from a Chinese pagoda. If you were really trying to maximize variety, you should have a bunch of buildings that look “modern”, a bunch of buildings that look “traditional”, and a bunch of buildings exploring weird spaces in between or totally different from either. Instead every building looks modern in about the same way.

Why doesn’t anyone make a building with the structure of top left, but the color and decoration theme of bottom-right? Wouldn’t that actually be new and unusual?

Demost gives us a story from Germany:

The Berlin Stadtschloss (“city palace”) was reconstructed in the last 10 years, and has just been officially inaugurated last week. It’s mostly a reconstruction of the old style, with lots of ornaments.

There was (and is) a furious debate on whether the reconstruction should be in this ornamental, reconstructive style. As far as I can tell, one side of the debate included most of the architectural/artistic world, who would have favoured something modern and condemned the reconstruction as “fake Baroque palace.. a stage-set of an old capital, with phony, manufactured charm, erasing traces of the bad years of the 20th century.”

The other side was the general public, who generally was in favour of lots of ornaments and its beautiful aesthetics. Perhaps untypically, the general public won this fight.

Fluffy Buffalo finishes the tale:

Except it didn’t, really. Three sides were reconstructed in original, ornamental styles, and the fourth, facing the river, was designed in modern plain blocky-rectangly style ( https://www.smb.museum/nachrichten/detail/eroeffnung-des-humboldt-forums-am-17-dezember-2020/ ) … and I was struck by how ugly it is, and how pointless the outcome of that redesign was.

And Webster gives us stories from Macedonia and Austria:

I think Skopje is a major counterargument to Scott’s claim about people preferring traditional architectural styles. Briefly, the Macedonian government decided to build a bunch of public buildings and monuments in a neo-classical style to remind everyone of their ancient heritage - it looks awful, and everyone inside and outside the country agrees that the buildings are super kitschy and shouldn’t have been built.

My interpretation is that people prefer old buildings, not old-style modern buildings. The 19th century saw a large number of buildings built in revivalist styles, mostly neo-Gothic and neo-Romanesque, but most of these buildings are forgotten nowadays (compare the relative popularity of the Stephansdom and the Votivkirche in Vienna - they look the same, they’re both located right in the centre of the city, but the Votivkirche barely gets any visitors).

I’m including this because I was in Vienna last week, I went to Stephansdom like everyone else, and then I got lost and stumbled into Votivkirche and thought - wait, this is at least as good as Stephansdom, why isn’t it in any of the tourist books, how come nobody else is here, what’s going on?

Maybe this is even more proof that I don’t have taste.

Deiseach gives us some more information about Luigi Bocconi University (the modern building on my comparison graphic). You can read the comment if you want to see the whole thing, but she quotes part of the architects’ prospectus, eg:

In order to make this grand place of exchange we thought about the research offices as beams of space, suspended to form a grand canopy which filters light to all levels. The offices form an inhabited roofscape. This floating canopy allows the space of the city to overlap with the life of the university. Allows internal and external public spaces to merge. The beehive world of the research is physically separate but always visually connected to the life of the lower levels

The underground accommodation is treated as an erupting landscape which offers support to the inhabited light filters above. Spatially this underground world is solid, dense and carved. We tried to establish a continuity between the ‘landscape’ of the city and the ‘made landscape’ of this undercroft […]

I used to hate this kind of stuff - it always reminded me of that one really pretentious Pepsi logo. But I recently visited the Sagrada Familia Museum, and it had quotes from Gaudi’s notebook, and he sounds exactly like this. So maybe it started with brilliant architects actually having thoughts like this, and then everyone else had to fake it in order to keep up?

Several people brought up opinions that the first generation to make non-traditional art (eg modern architecture, impressionist painting, Art Deco, jazz, e.e. cummings) were very good, original, and actually quite interesting critiques. Then every generation after that was terrible. They suggested something like that rebellion is good and constructive when you have a very specific thing you’re rebelling against, understand it inside and out, and are still in some sense “constrained” by the world it created, and then the generation after you doesn’t understand the traditional forms at all and just sort of does vague rebellion-adjacent things cluelessly in the hope of capturing some of the original energy.

This reminds me of Athrelon’s claim that first-generation Chinese-American immigrants insist on slavish adherence to all the (seemingly pointless) rules of Chinese culture, second-generation immigrants have the good parts of Chinese culture (driven, intelligent, lawful) without the bad parts, and third-generation immigrants lose the good parts and become indistinguishable from other Americans. Maybe rebellion can be good and productive for one generation, and after that you’re just confused.

Simultan writes:

You may find my interview with the neo-romantic composer corentin boissier interesting: https://www.erichgrunewald.com/posts/interview-with-corentin-boissier-romanticism-modernism-composition/

CORENTIN: Always wanting to experiment further, to move forward, is part of human nature. The use of new chords and more and more complex rhythms in order to express as closely as possible the spirit of the new times has led to the dissolution of tonality. As long as it remained natural, this evolution produced masterworks in which tradition and novelty coexist in infinitely variable percentages. The dosage was sometimes explosive, sometimes tousling, but often successful.

Today, I’m more convinced than ever that there is no natural border between styles. The schools may be opposed but not the styles, which should complement each other. But in the 1960s, suddenly it was all about serialism and electro-acoustic music; there was the quasi-institutional obligation to wipe out the past, and the subsidies only went to what has been called “contemporary music” (the word “contemporary” being abusively linked to a style instead of just meaning “of our time”). Without this political, ideological, and basically non-artistic doctrine, there would have been a natural complementarity between tradition and innovation, in music as in all other arts.

[…]

ERICH: I know some great American composers, like Arnold Rosner and Harold Shapero, have spoken of having felt alienated in American music departments, due to the dogmatic serialism there. In your experience, have the conservatoires of Paris been more accepting of 19th-century idioms?

CORENTIN: Absolutely not – quite the contrary! Western Europe, and France in particular, has spearheaded this systematic destruction of all artistic tradition, of any style that could be related to the past. The conservatories have been forced to practice a clean slate policy. This undermining action, well supervised by the institutions and the media, has had the disastrous result that, for several decades, composition – in the original sense of the word – is no longer taught in the conservatories. I did all my musical courses at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique (CNSM) of Paris. I obtained five Prizes … but I was not able to attempt the “Composition” Prize since this Prize is only for composers of so-called “contemporary” music, that is to say “experimental”.

Many people recommended books or papers on this subject. I haven’t read them yet, but the most enthusiastically mooted were:

The Work Of Art In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction

From Bauhaus To Our House

The Rite of Spring by Modris Eksteins

Art and Culture: Critical Essays by Clement Greenberg

The Intellectuals and the Masses. Pride and Prejudice among the Literary Intelligentsia 1880-1939

Shock of the New (TV series)

The Civilizing Process by Norbert Elias

Distinction by Bourdieu