Highlights From The Comments On Orban

Lyman Stone on Twitter:

Lyman Stone 石來民 🦬🦬🦬 @lymanstoneky

Here’s the @slatestarcodex piece: astralcodexten.substack.com/p/dictator-boo… Overall, I agree with a lot of his assessment of Orban. But I want to quibble on two points: 1) The relationship between dictatorship and democracy 2) “Why admire Orban?”

astralcodexten.substack.comDictator Book Club: Orban…7:16 PM ∙ Nov 5, 2021

I won’t make you read it all in tweet format. He continues:

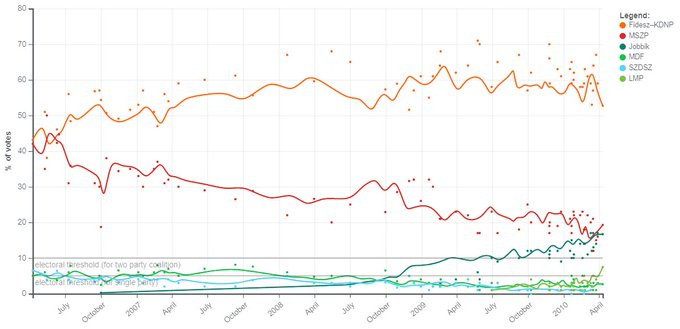

1) Dictatorship and democracy. The arguments about Orban cheating in elections might be totally true. I dunno. But that’s sort of irrelevant. Neutral opinion polls nobody disputes show he would have gotten 2/3 under almost any system.

His crude poll share was about 60% before the 2010 election, but given the threshold effects, he’d likely have ended up at a supermajority under almost any system. And as @slatestarcodex [says], a lot of the initiatives that the EU most despises under Orban are initiatives that everyone agrees have supermajority public support among Hungarian voters.

Moreover, I agree with @slatestarcodex that if public opinion turned in Hungary, Orban would probably turn on a dime too. The dude loves power. But that should inform our read of what’s going on in Hungary. Hungarians wanted a right-nationalist authoritarian leader, and so they voted for one, and the electorate has wanted recurrent intensifications of that regime. So is it a dictatorship? Or is it a democracy?

This gets at the problem with “democracy” as a concept. Hungary is undeniably Democratic: there is widespread public support for the regime, which is selected by elections, the results of which are a decent approximation of trustworthy and neutral opinion polls. But I think it’s still possibly reasonable to call Orban a dictator. He wields enormous personal power, there are few checks on his power, and he uses power to create a personal clique of supporters to perpetuate that power and enfeeble the competition.

But this is the point: Democracy and dictatorship aren’t opposites. In fact, they are natural companions! So much so that before the 20th century, “democracy” was often used literally as a synonym for “authoritarian and demagogic rule”! Orban is a great example of why the word “democracy” came into ill repute in the past: because it was widely understood that “the people” (often pejoratively “the mob”) will often vote for a strongman to stomp his boot on the face of disliked others. That’s not so much a disagreement with @slatestarcodex as just a comment where I think the modern western liberal mindset obscures understanding the phenomenon of populist leadership.

2) Why admire Orban? Here I think @slatestarcodex misses some important stuff, perhaps because his biographies miss it. Yes, Orban was incompetent in the 90s. So were MOST immediate post-Soviet leaders! And while Orban may have been corrupt, you can compare the personal wealth of the Fidesz clique to the cliques that looted Russia or Ukraine and realize that Hungary got a better class of corrupt leaders than much of eastern Europe. Moreover, Hungary actually had competitive elections with changes of power and leaders who respected those results! Maybe they were dirty but, like, it happened! This wasn’t universally true!

So why might Hungarians admire a dissident-cum-parliamentarian who competed for their votes and when defeated responded democratically by adapting to try to win the next election? Because…. duh?

But it’s not just that. The big factor that’s absent in all these culturalist accounts of Hungarian politics is…. the economy. Hungary went from below-average unemployment rate for its region under Orban 1 to way above-average under the socialists to again below-average under Orban 2.

This is extremely important. A part of Orban’s appeal is that, whether by coincidence or art, he has managed to preside over periods where Hungary’s economic performance was better than a lot of its neighbors, and often fairly obviously so. That is, supporting irredentist nationalism in the form of Orban hasn’t imposed costs on Hungarians: they aren’t like facing sanctions or something or enduring deep economic hardship to stand by their dictator. He’s delivered (comparatively) good times!

So when you have a leader who 1) seems marginally-less-corrupt than regional peers, 2) delivers marginally-better-results than regional peers, and 3) adopts policies that are widely popular….that leader will be popular! Duh!

Okay so finally a bonus 3). @slatestarcodex says this:

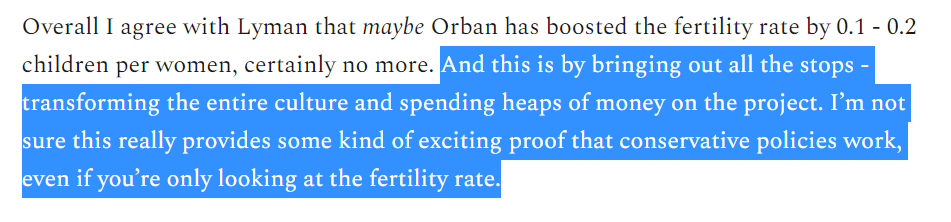

But your regular reminder that IT’S NOT TRUE. Under Orban’s government, family spending as measured by the OECD has actually declined on a per-child basis! This whole story about redesigning the whole culture is wrong! Indeed, a core part of my critique of Orbanism is precisely that I don’t think it’s radical enough. It does a lot of flashy stuff…. funded by cutting other programs, and with little eligibility quirks that end up limiting who benefits from it.

So all that to say….

1) Orban may be a dictator, but he is absolutely also a democrat.

2) Orban is popular because he has delivered popular policies and results

3) The pronatal stuff is a lot more talk than money (tho that’s starting to change)

My main question here was about point 2 - how did Orban do so well economically. BobbyP gives what I think is a plausible answer:

One missing angle from this post is the EU accession of Hungary in 2004. This opened up two things: 1) Access to the single market for a country with low labour costs 2) turned on the taps of EU aid money.

Hungary has been riding a wave of economic growth based on EU accession. the economic growth has driven support for Orban as a leader overseeing raising living standards, and dished the aid cash out to supporters.

Richard Hanania on Twitter:

Richard Hanania @RichardHanania

Richard Hanania @RichardHanania

Orban is a dictator because… he wants to exert more democratic control over the bureaucracy? This is the “democracy” game. You can take power away from elected officials or give them more, either way can be “undemocratic” according to democracy watchers. astralcodexten.substack.com/p/dictator-boo…

[12:13 PM ∙ Nov 5, 2021

92Likes12Retweets](https://twitter.com/RichardHanania/status/1456595627471605770)

Well no, he’s a dictator because he owns 80% of the media that’s supposed to be critiquing himm and has rigged elections in various ways. But I agree there’s an interesting question of “is exerting more democratic control over the bureaucracy an additional black mark against him”?

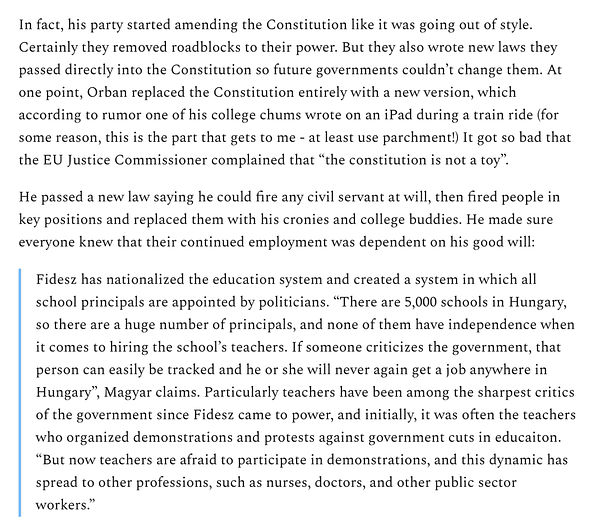

Before we get there: I interpreted the paragraph Richard quotes as claiming that, if a teacher or doctor protests Fidesz or Orban in their spare time , as part of the normal exercise of their rights as a citizen, they can get fired or otherwise see their career suffer. That doesn’t seem to me like the government exercising control over the bureaucracy, that seems like a nightmarish escalation of the “cancel culture” that both Richard and I are against. In fact, this is an unusual but kind of compelling argument for directionally privatizing education and health care; if the government controls the hiring, promotion, and firing process for people in education and health care, that makes it harder for people in those fields to stand up to authoritarian regimes. But if you’ve got to have a government that controls major industries, and you want to leave room for democratic rights, you’ve got to have some kind of firewall between people’s off-the-clock activities and their government-sponsored careers.

But suppose I’m misinterpreting that, or put that aside. Are governments that try to control the bureaucracy more authoritarian than ones that don’t?

One argument in favor: I think most of us would agree that a government (here used as eg “the Tory government”, a particular political regime) which tries to control the judiciary and pack it with supporters is more authoritarian than one that doesn’t. A democracy is supposed to have some number of independent power centers to provide checks and balances, and if you put too much effort into making every power center bow to you, you stop having checks and balances, and become authoritarian.

But also, if you’re the democratically elected government, and you’re supposed to be setting idk housing policy or something, and the Department Of Housing Policy is refusing to implement any of your ideas, or implementing them incompetently, or just seem like total morons, then yeah, it seems natural to want to get rid of them and replace them with ideologically aligned and competent people.

I think the undercurrent to Richard’s complaint is that right now the situation is asymmetric: most bureaucrats are by nature liberal, and so when a liberal regime is in power, it can cooperate with the bureaucracy, and when a conservative regime is in power, it has to try to struggle with and overcome the bureaucracy, and that unfairly (?) makes conservative regimes look more authoritarian than liberal ones.

I’m not sure I have enough knowledge and context to have a strong opinion on this right now.

Sholom writes:

I don’t really see how Orban qualifies as a dictator. Even with the absurdly gerrymandered electoral system and the corrupt influence buying, Hungary is still a democracy and Orban is still a democratically elected head of state. To my mind, the line separating democracies from dictatorships is whether or not a majority of the people can vote out the party/leader in power, and whether or not people can openly campaign against the party/leader in power without being arrested or murdered. Both things are still pretty clearly true in Hungary. If Orban were to rig an election or violently repress his opposition, he would hop right over that line, but I don’t think even his harshest critics have claimed that he’s done that yet.

All democracies exist on a spectrum from more-or-less gerrymandered and more or less corrupt, but even the ones at the extreme end of the spectrum are still in fact a democracy.

Yeah, this is fair. I called this series “Dictator Book Club” because it had a nice ring to it, but I don’t want to assert that I definitely know what dictatorship is, or that Orban definitely qualifies.

Orban himself calls his regime an “illiberal democracy”, which seems as fair a description as any. Technically people vote, and probably the elections are even mostly fair, but things are rigged enough behind the scenes that it’s really hard for the elections to matter.

In the US, there are a lot of controversies over the democratic process. Should people be allowed to vote by mail? Should they have to show voter ID? Should DC and Puerto Rico be states? Who should get to draw district boundaries, and how? Are the rules distributing Senate seats fair even when they give people in rural states more votes than people in urban ones? Should social media be regulated, and if so, how? How should candidates be allowed to raise money? Are there enough voting booths, and are they in the right places? What’s the threshold for demanding a recount?

If one of the two major parties got to answer all these questions the way it wanted, how many votes would that be worth? Would it turn 49% into a victory? 45%? 40%? If one of the two parties was allowed to create its own system from scratch, and it was allowed to be at least as weird as the Electoral College is now, how many votes would that be worth?

Sholom writes that “All democracies exist on a spectrum from more-or-less gerrymandered and more or less corrupt, but even the ones at the extreme end of the spectrum are still in fact a democracy.” I am less sure. Imagine an electoral system where if every single person nationwide unanimously votes Republican, the Republicans win, but as long as at least one person votes Democrat, the Democrats win. Is that a democracy? Is there any real-world difference between that the world where the Democrats just never allow anyone to vote at all and stay in power forever?

Imagine that Democratic sympathizers control every newspaper and TV channel, and fill them with propaganda all the time (obvious joke is obvious, save your breath). Imagine that they control all the social media sites and ISPs, and they all “voluntarily” “self-censor” and delete any conservative opinions or criticism of the government. Nobody even knows what a Republican is, except some vague signifier of evil. Every four years, you’re presented a ballot with the name of your beloved Glorious Leader and some other guy you’ve never heard of with an R next to his name, who you can only assume stands for pure evil and everything you hate - but you are absolutely allowed to vote for that other guy if you really want to. Is there any real-world difference betwen this world and the one where the Democrats just dispense with elections entirely?

It seems more like democracy and dictatorship are on a spectrum, with Orban in the awkward middle where we don’t really know what to call it.

Furrfu writes:

“Some kind of hybrid regime that keeps the trappings of democracy” is a trick that goes back at least to Caesar; that’s why Caesar was called an “imperator” (usually translated into English as “emperor”, but previously it was a military term meaning “commander”) and “dictator” (a sort of commissioner with emergency powers, prior to Caesar always being temporary) but never a “king” (“rex”) like Tarquin. The Roman Senate was the governing body in the Republican period, but it continued to exist all the way through the entire Western Empire and for another century-plus after the Western Empire fell; and, in the East there was still a Roman Senate for another 600 years after that, though not quite until the final fall of Constantinople.

So, rather than saying that this is “one of the big stories of the late 20th/early 21st century,” I would say that this is one of the big stories of the first century BCE to the 12th century CE. This is precisely how the Roman Republic was destroyed. And it’s far from novel even in modern times.

The USSR retained the trappings of its bottom-up grassroots democracy (that’s what the “soviets” were) even while the Party took over real control.

Here in Argentina, our Congress has served unbroken since 01854, 167 years, despite coups installing dictators in 01930, 01943, 01955, 01962, 01966, 01971, and 01976, plus Perón taking Orban-style measures to consolidate his power to such a frightening degree during his first period of rule (01946-01958, during which he changed the constitution to permit his re-election) that in the 38 years since the restoration of democracy in 01983, the party Perón founded has ruled for 27 years, and other parties only 11 years.

In Venezuela, Maduro is clearly a dictator, which results from Hugo Chavez gradually clearing out all the obstacles to dictatorship. But Chavez himself was never a dictator, and he always preserved the forms of democracy, in fact greatly strengthening them in appearances. But at the same time, he weakened them to the point that his successor would face no significant opposition.

It’s the same in most recent dictatorships. Hosni Mubarak held multi-party elections which he won, and the Egyptian Parliament was never dissolved during his brutal reign. Pervez Musharraf held elections to, in theory, decide whether he would continue in power, but nobody else was allowed to run. Hungary itself, though Communist, was theoretically a parliamentary republic from 01946 to 01949 and still had a multiparty legislature until 01953; even after opposition parties were prohibited from running candidates, the Hungarian Parliament continued to hold regular elections, and many independent (that is, non-Communist) candidates continued to gain seats.

Quite Likely writes:

Should probably plug here that Hungary has elections coming in 2022 in which all of the non-Fidesz parties have united into a single coalition, and are currently leading in the polls. Unclear how much that will matter given all the gerrymandering, but this is the most significant threat to Orban’s power in a long time: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/oct/28/hungary-anti-orban-alliance-leads-ruling-party-in-2022-election-poll

And suigeneralist adds:

It looks like the opposition might win! Betting markets are not particularly liquid but one bookie is offering odds which imply a 60-70% chance that Fidesz will not win a majority at the next election. https://www.olbg.com/blogs/hungarian-general-election-betting-odds-and-history

Yeah, I guess that would be pretty embarrassing for the “Orban is a dictator” theory - and for the author of the book I read, who hammered in how thoroughly Orban had subverted democracy and how it was basically impossible anyone could beat him.

Stevenjbc writes:

All of the things you accuse Orban of doing, are routine with the Left in most Western countries. In fact, if he ever rigged an election it could be called “fortifying” it (see NYT on February 4, 2021).

There were a lot of conservatives in the comment who made basically this point, or who compared various things Viktor Orban did to various things Joe Biden (actually or imaginarily) did.

I don’t super want to get into a protracted argument about which things are equivalent to which other things, but here’s one point that I think drives home the extent of the difference between them. From the Lendvai book:

Kerekes demonstrated how the rules of parliamentary procedure as amended on 1 January 2012 have enabled the adoption of urgent emergency legislation requiring no debate…with this measure, it is now possible in peacetime to rush a bill through parliament in less than forty-eight hours […]

The approval of the internationally controversial erecetion of a fence along Hungary’s southern border to keep out refugees, as well as the authorization of the army’s deployment to police it, was dealt with in barely two hours…An admistrative record was achieved on 21 September 2013: the amendment of a law was passed, from its first oral proposal in parliament to a final vote, in a mere ten minutes.

I think one simple signal that Orban has garnered more power than Biden is that Orban got a major controversial law passed in two hours, whereas it took Biden six months to pass a bipartisan infrastructure bill that as far as I can tell nobody actually disagreed with.

And yeah, it’s really bad that the US can’t do anything in less than six months and often doesn’t do it at all. A Congress that can pass important legislation in a few hours feels like a dream. To some degree there’s a tradeoff: if it’s hard to do anything, then it’s hard to oppress people; if it’s easy to do stuff, some of the stuff that gets done is bad. I don’t think we’re at the right point in that tradeoff right now and maybe removing a couple of checks and balances, like the filibuster, could be net good (or maybe it wouldn’t be, I’m not sure). But if you remove every single one of them and the leader can pass laws in ten minutes, then I think it’s fair to worry that you’ve lost some important aspect of liberalism.

Carl writes:

I’m a compatriot and contemporary of Orban’s. I grew up in the Hungarian countryside and my single-mother (!) rose through the ranks in the Kadar era, she finished college when I was already a toddler in the day-care. She nfetched water from the well and coal for heating from a shed at the house that the village provided for her as the teacher in the village school. We moved from there when I was five. The next teacher who moved in still had to do that as far as I know for until the late 80s or early 90s. I worked hard on my grandparents small farm (the size that was still allowed) and I was actually working in the sun in the vineyard with my grandparents and my mother when Orban gave his speech in June 1989. We were listening to it on the radio.

Such an upbringing means nothing really. Hungary and countries like that had a shift in those years; I’m not quite sure if I refer to the right framework, but I think what was going on is that Hungary was becoming an income level 4 country out of an income level 3 (Rosling) in the 1970s. Orban’s experience was pretty standard. The accent thing is nothing either. Orban has plenty of complexes, accent never stuck me as one. It hardly ever is in Hungary. There was a lot going on with him at the turn of those decades. I would dig into Soviet/Russian intelligence measures. The poor boy and the accent thing might pique Anglo-Saxon people’s interest. It isn’t an issue with his contemporaries in Hungary.

Several people chided me for genetic essentialism in my paragraph about Magyars. Erusian writes:

The Hungarians are descended from steppe nomads to at least the extent that Americans are descendants of the English. You can equally say most Americans have very little English blood and have it be true but a weird take. Now, Magyarism as a nationalist ideology is full of weird false facts. The idea they’re the Huns that invaded Rome is just plain false. But there’s significant linguistic and cultural continuity between Hungarians and their ancestors in addition to a distinct ethnic gene cluster. The article you cited itself even says this. Now, do they have large amounts of Germanic (and even more Slavic) blood? Yes, absolutely.

The analogy seems weird - I think most Americans who think they’re of English descent are, and nobody ever claimed the Italian-Americans, blacks, Hispanics, etc were descended from Englishmen. Still, the point about cultural descent is well-taken.

You can read the rest of Erusian’s very thoughtful 14-part comment here.

Several people pointed out reasons why Orban’s wall worked but Trump’s wouldn’t. E Dincer writes:

I think the main difference is that there isn’t a 3rd country at the USA-Mexico border and USA is the target country for immigrants anyway. Hungary is just one of a several countries on a route from Middle East to Western Europe, so if they make their wall slighly more inconvenient than the neighboring countries that’s enough to sway the torrent of immigrants another way.

Act II writes:

1) Unlawful entry only accounts for a small portion of illegal immigration in the US, with most immigrants entering legally and overstaying their visas. This article was the first Trump-era hit on the subject I found on Google. As far as I can tell, the current numbers are similar, with there being about double the number of visa overstays annually as unlawful entries. Obviously a wall would only affect unlawful entry.

2) The wall would not necessarily be effective at preventing unlawful entry in the long term for practical reasons. America’s southern border is almost 2000 miles long and crosses several different types of terrain. The barrier would not only need to be built, but manned and maintained across this huge distance. This task is much cheaper and easier for a country like Hungary, whose barrier is only 325 miles.

Argument 1 is hard to dispute. If your overall goal is to reduce illegal immigration, it’s not very cost-effective to spend billions to maybe reduce it 30%. Argument 2 is weaker in my opinion; I think it’s probably true, but impossible to really prove without actually building a wall and finding out.

Some other commenters bring up counterarguments. The US has much more border to defend than Hungary, but it’s also much bigger and richer than Hungary. visa overstays and illegal crossings seem to fluctuate in importance, and crossings can be the majority of illegal immigration during some years.

Speaking of immigration, polscistoic writes:

A few points on EU immigration policies that seem not to have been noticed by non-European ACT readers:

EU refugee migration is regulated according to the so-called Dublin agreement. The core point is that a refugee must seek asylum in the first EU country he/she enters.

This means that if you have a large border with a non-EU country, EU countries further inland can send refugees back to wherever they first entered. Since Hungary has a border with non-EU countries, the Hungarians risk being stuck with refugees, even if the refugees themselves would prefer to move further West or North. (The problem is even larger in countries like Italy and Spain.)

…A North American equivalent would be if there had been an agreement between Canada, US and Mexico that refugees could be returned to the country of “first entry” – which would usually be Mexico. For obvious reasons, Mexico would not have been happy with such an agreement (and EU countries bordering on non-EU countries, including bordering on the Mediterranean, have also tried – so far unsuccessfully- to change the Dublin agreement).

Are other EU countries secretly “happy” about the Hungarian border fence, as some commentators suggest? Well, because of Dublin, they should not really care that much, since they can legally send refugees crossing from Hungary back to Hungary.

Notice that it therefore makes sense for Hungary to build a fence, since they risk being stuck with refugee migrants thanks to Dublin.

THANK YOU. I had been really confused why Hungary didn’t just buy every migrant a train ticket to Germany (where they all wanted to go anyway) and tell them to have a good time.

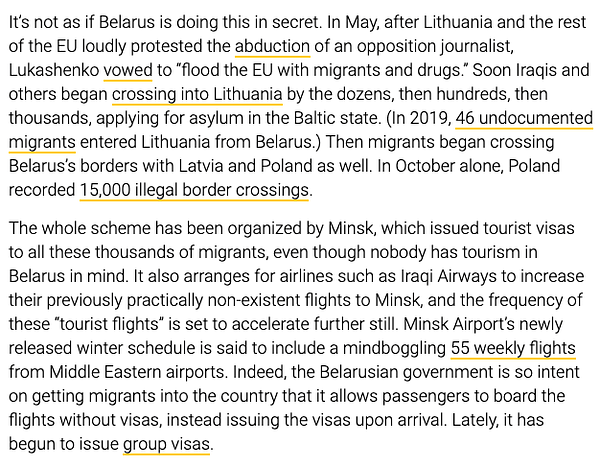

On a related note, the EU migrant situation might be about to get pretty weird:

Minsk airport is now receiving 55 flights per week from the Middle East, part of Belarussian govt effort to destabilize EU neighbors by flying in refugees and bussing them to its borders defenseone.com/ideas/2021/11/…

[6:39 PM ∙ Nov 10, 2021

186Likes123Retweets](https://twitter.com/tomgara/status/1458504482996817922)

Mikk writes:

I am quite surprised about the review. I am no expert of Hungary, but my understanding has been a bit different.

My impression (even reading opponents of Orban) has been:

1) Fidesz rise to power was caused by Socialists, their corruption and mismanagement of Hungarys economy.

2) “We lied” tape was leaked in 2006, Fidesz won elections in 2010. The review gives an impression that these two events were closely related. They were not.

3) Reading opposition newslets of Hungary, I would say that up until 2013-2014, their main narrative was: socialist were bad, Fidesz promised change and won, thats the reason, not leaked tapes or tricks by Orban. And (grudgingly) Orban has delivered change and improved economic situation of Hungary, that boosted his status even more. From 2013-2014 stories about corruption, anti-democratic measures etc have became more prominent.

4) For most of his political career Orban was described (even by his opponents) as quite ordinary right of center free marketeer. Just recently reread some stuff from Anne Applebaum, typical liberal cosmopolitan, what she said about Orban: “For 20 years we were on the same side”.

5) I am not hungarian, but I am from Eastern-European country. I do not think that hick vs urban elite applies here. If talking about social status and background, communism (and fall of communism) changed so much, that everything else is irrelevant. I am coming from a small Baltic country and most of our political parties have their historical roots in different underground movements of 1980-s. 30 years late you can still see lot of friends, schoolmates, roommates in politics. So, I am not surprised that smth similar can be seen in Hungary.

6) I am not sure what to make about gerrymandering. It seems that Orban has used it to benefit himself, but I have read some credible people who say that these accusations and effects of gerrymandering have been overblown.

Overall, I am on the fence. Having watched situation in Hungary for years, it seems to me that critics of Orban (especially from the outside) are a bit biased, they simplify, exaggerate and misinterpret sometimes. At the same time, I also cannot agree with defenders of Orban, who say that nothing is wrong and they attack him only because he is conservative. This does not seem true either.

DannyK writes:

You don’t even mention Orban forcing a whole university out of the country, which I think is the single most dictatorial thing he’s done.

Yeah, I didn’t get into Orban’s crusade against George Soros. I think all the “no worse than Biden” people would have been extra angry about that one; is this different from the US crusade against the Koch Brothers?

Maybe the difference is that it feels potentially anti-Semitic? But the same week I wrote my post, Congress was interrogating the Facebook whistleblower about what’s basically an accusation that a manipulative Jewish billionaire is responsible for all the political opinions we dislike, in a way contradicted by all the evidence. I think billionaires with political influence, Jewish or not, seem to be unpopular everywhere.

That having been said, I disagree with this tendency, and Soros is a good example of why: billionaires are independent power centers who are able to build things without government approval, and so they play an important role in pushing back against authoritarianism. Orban trying to shut down Soros’ university was bad and I hope they’re able to figure something out to stay in Hungary.

Vicoldi writes:

As a Hungarian, I found some glaring problems in the review, almost enough that I feel myself in a Gell-Mann Amnesia situation. I don’t really blame Scott though, getting informed about the politics of a foreign country is very hard. Still, I trust the Erdogan and Modi reviews significantly less now.

First of all, I broadly agrre with the personal characterization of Orban, and I also think he is an extremely corrupt leader and a threat to democracy.

The review doesn’t even mention some of the worst strikes against him: his schoolmate from his home village, who he got to know while going to the same football mathces is now the richest person in the country, whose hand is in every conveivable industry. Everyone knows he is Orban’s straw-man, and collects the money for him and for his political cause.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C5%91rinc_M%C3%A9sz%C3%A1ros

Also, at one point, Orban’s agents secretly bought up the largest Leftist newspaper, Népszabadság, and simply cancelled it. In the post Too Much Dark Money in Almonds, Scott wonders if there is so surprisingly littel money in politics, why doesn’t some billionaire simply buy up all the newspapers and get to control what people hear about. Orban did exactly that, using the money his straw-men, like Mészáros, got from corruption.

On the other hand, the review is probably based on books and articles seriously biased against Orban, which causes the review to be seriously misleading about a number of things.

Most importantly, the gerrymendering problem is way less serious than the review portrays. I looked up the population of electoral districts, and all have population between 75 000 and 102 000. I couldn’t find a source how the article quoted in the review got that 1 Fidesz vote = 2 Left votes, but it must have used some very creative accounting. I suggest that this quote should be removed form the review, unless it is supported by more sources, because I stronly suspect it is just blatantly false.

Also, you can just look at the election maps: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2014_Hungarian_parliamentary_election

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2014_Hungarian_parliamentary_election

Orban won almost all districts. There is no gerrymendeing that can explain that.

The main change Orban’s new Constitution brought was that previously Hungary had more or less a proportional electoral system: every party gets seats in the parliament proportional to the number of votes they got. On the other hand, if I understand correctly, in the UK, every district delegates one member of the parliement with first-past-the-post voting.

In my opinion, both system has advantages and disadvanteges, the German system is more balanced, but its result is that usually no party has parliamentary majority, which forces them to form coalitions, which can be a nightmare of instablility (eg Italy).

Orban changed the Hungarian electoral system to be a mix of the two: there are 199 seats in the parliament and 106 districts delegating members with first-past-the-post voting. The other 93 seats are distributed among the parties proportionally with the votes they got. (On a ticket, you vote both for a delegate in your district and you also vote for a party.)

I think this system is not entirely unreasonable, although the first-past-the-post element gives the winner more seats compared to the previous system, so it is easier to win 2/3 majority. But this also means that it is aeasier for the opposition to get 2/3 and remake the changes (although it is very unlikely that they will get that in this election).

The votes from abroad are also seriously overemphasised in the review. It is true that they overwhelmingly vote for Orban, but only the 4% of votes come from abroad, and they don’t have district delegates, so that’s like 4 seats from the 199. Significant, but Orban’s power doesn’t depend on these few seats.

I had some othe minor problems: Orbán emphasisees Christian, not Catholic ethics, as Hungary has a significant Protestant population (Orban himself is Protestant). The review claims that Orban was pretty bad in governing during his 1998-2002 leadership, meanwhile I usually hear from older friends, both left and right, that Orban-government was reasonably good back then, they were a moderate center-right party and mostly played by the rules. Most people I know claim that Orban only really broke evil when he lost the election of 2002.

Also, I feel the review is a bit too kind to Socialist leader Gyurcsány: when he gave the infamous speech, he was already the prime minister for two years, the speech is about his premiership, not his predecessor’s. And after he was caught on tape claiming he lied all day and night and meanwhile didn’t do anything good, he refused to step down. He used police brutality against the protesters and governed for three more years while being probably the most hated man in the country. No wonder Orban won in a nandslide after that. And Mr Gyurcsány still didn’t step down after that, because there is approximaeetly 10% of voters who are really devoted to him, so he can remain an important figure in the opposition to this day, while the majority of the country still loathes him for his speech, for the police brutality and for mismanaging the 2008 recession which hit Hungary especially hard. Any reasonablye person would retire in his place, but he is never going to, because he is as much of a mud-fighter as Orban is. A big part of the reason the Left can’t beat Orban is that they can’t throw out Gyurcsány and his devoted supporters, but they can’t win until he is on the ticket.

Also, border wall: not long after Orban built his wall and was called a fascist for that, the Germans also panicked after the first one million migrants poured in in a few months, so they made a deal with Erdogan, and paid Turkey not to let in more migrants to Europe, so now most Syrian migrants are stopped on the turkish border, sometimes by gunfire.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/18/eu-deal-turkey-migrants-refugees-q-and-a

https://www.dw.com/en/turkish-border-guards-accused-of-shooting-at-syrian-refugees/a-42444813

Orban is understandably bitter about being called a fascist, when in a sense he was just ahead of the curve, and I agree with him that EU leaders were pretty hypocritical about this. Also, before Orban bouilt is wall, leftist critics in Hungary also confidently calimed that it won’t stop any migrants, but it did. I give it a nice chance that Trump’s wall would work too.

Overall, Orban is still very bad, and I agree it is a shame that some western right-wingers are admiring him, but his critics often seriously exeggerate: somewhat similarly with the situation with Trump. If you only hear about Trump from texts written by angry leftists, you will get a very biased image, hited with a few banal lies. Scott has some good articles from the past calling out some of the craziest accusations against Trump. There are a similar number of absurd accusations written about Orban in the western media, but fewer well-informed people calling them out. So treat everything with a grain of salt.

The most common comment was that it was a stretch to call Orban a dictator. Maybe I’ll rename the series - Autocrat Book Club? Political Leader I Am Uncomfortable With Book Club? Suggestions are welcome.

But I think it’s doing its job of raising tough questions. I asked what Orban had accomplished that conservatives could be excited by. After reading your comments, I think I understand the answer better: it’s not any particular policy, it’s that he was able to gain and hold power despite being conservative.

The idea is something like: there are a few ways to govern. One is to be Angela Merkel. Be more or less an elite, who only likes things other elites like. Then you can do things like have an independent judiciary (because the elites in the judiciary will mostly be nice to you), have an independent media (because the elites in the media will mostly cover you positively), have independent academic experts (because they will say the evidence supports you), etc.

Another is to be Donald Trump. Go against elite opinion, have all of the elites hate you, and - realistically - don’t accomplish very much. When you try to accomplish something, the courts will declare it unconstitutional, the media will attack it, and academic experts will say the evidence is against it. You can ram the government really hard against all these other institutions and try to break past by sheer inertia, but it’s a tough battle.

Another is to be Viktor Orban. Go against elite opinion, and when the elites try to stop you, crush them. Crush the judiciary and replace it with your college friends. Crush the media and replace it with your college friends. Crush the intelligentsia and replace them with your college friends. Then do whatever you want, and the judiciary, media, and intelligentsia will take your side!

…is I think how conservative Orban supporters model the situation. But I’m not sure it’s that simple. Trump had a lot of problems getting anything done. But Biden isn’t having an easy time either, judging by the increasingly-shabby-looking reconciliation bill. If Biden wants $3.5 trillion in spending, a tax on unrealized capital gains, and maybe Medicare For All for good measure, who does he have to crush? Maybe the “liberalism = hewing to elite opinion = playing on easy mode” equivalence isn’t the right way to think of things.

Okay, fine. So regardless of your politics there’s a tiny Overton Window of things you can actually get done, things that you can sneak past the gauntlet of various liberal and conservative elites trying to frustrate you at every turn. You can either do some minimal thing within this window - Trump’s tax cut, Biden’s spending-bill-lite - or you can crush all those people.

Crushing those people has a lot of positives. A while back, we reviewed the evidence that places that were conquered by Napoleon grew faster than places that weren’t, presumably because Napoleon crushed the previous rulers and then cleared the backlog of common-sense policies that nobody had been able to implement before. In America, we remember FDR as somebody who did something similar, for better or worse. Lots of people on both sides of the aisle dream of an FDR-like figure to do the same for what they consider common-sensical reforms - which is hardly new.

In the first model, the Orban-supporting conservative one, the maddening Lovecraftian revelation at the end was “either you’ll get whatever liberal elites want, which is awful, or you need someone who at least flirts with dictatorship.” In the second model, the politically-neutral one, it’s “either you’ll get stagnation and dysfunction, or you need someone who at least flirts with dictatorship.” Are either of these true?

We’re back to our old question of “What is a dictator?” I’ve been unconsciously working off a definition that has something to do with “somebody who tries to clear away the normal mechanisms of civil society in an attempt to make it hard for people to oppose them.” So shutting down the press, making it illegal to join opposing parties, committing voter fraud, that kind of thing.

You could imagine a system that has strong leaders who don’t fit this definition. For example, what about a country that elects an autocrat once every four years, the autocrat can do literally whatever they want, and then they stand for re-election (or not) on the strength of their accomplishments. If you get a really virtuous autocrat, maybe George Washington, this works fine. If you get anyone else, part of what they do in the “do literally whatever they want” phase involves making it hard for other people to vote them out. Part of the goal of having checks and balances is to make sure there are lots of different power centers and if one of them starts looking like they’re going to make a move against democracy, the others can unite to crush them.

Viktor Orban is, alas, not George Washington. He became powerful enough to get whatever policies he wanted (and if you’re a conservative, you can really appreciate the policies he enacted), but then used the power to make it really hard for the voters to remove him.

Are there systems of government that can let leaders take decisive action without degenerating into dictatorship? I have no good answer right now, and I look forward to exploring it further in whatever we decide to name this book club.

Tom Gara @tomgara

Tom Gara @tomgara