Highlights From The Comments On The 2020 Homicide Spike

Thanks to the 750 of you who commented on the homicide spike post (as of last weekend when I collated these highlights). I don’t have enough space here to address everything, but here are some general themes:

Was It Guns?

Artifex0 on the subreddit writes:

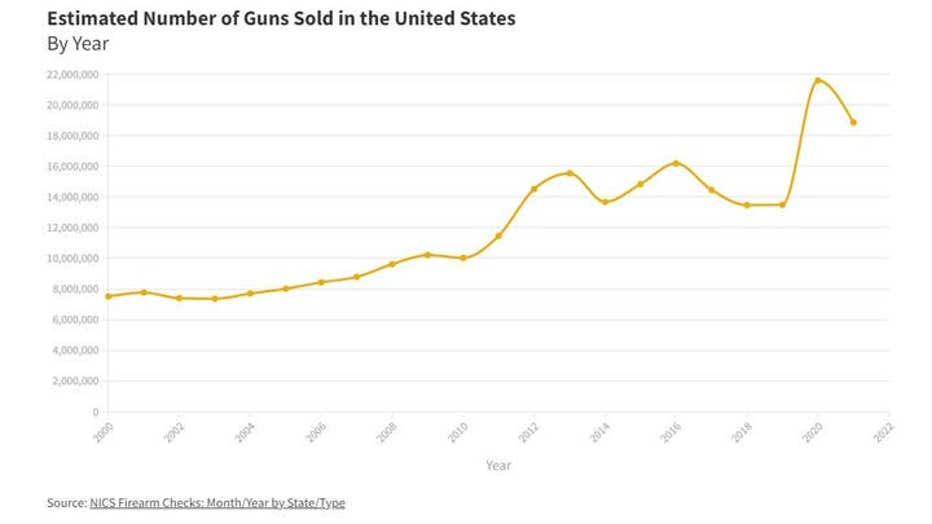

You mentioned that you haven’t looked closely into the idea that increased gun sales were to blame. I haven’t either, but that hypothesis immediately seems more plausible to me. Here’s a graph of gun sales showing the pretty big spike around the same time as the homicide spike

Guns are a much bigger factor in violent crime, which increased, then property crime, which decreased. Mass gun sales are a US phenomenon, with per-capita gun ownership in the US being the highest in the world, double the next contender and 5-10 times higher than Canada and Europe. If you’re motivated to commit a murder, then whether you currently have a gun seems much more strongly and directly influential than whether you’ve briefly noticed a police car in the neighborhood in the past week or whether the police seem worried about being cancelled.

[separated out unrelated paragraph here into a different section]

If increased gun sales largely motivated by the 2020 riots were the most significant factor in the spike, that would be politically inconvenient for both the left and the right- I’d expect good reporting on that to be a bit slim. It would also be politically inconvenient for libertarians, though I hope you’ll avoid the mistake of the journalists you criticize, and not allow politics to subconsciously shape how easily you reject hypotheses.

I accept I should have put more work in the original post into ruling out gun sales as the cause. That having been said, I still don’t think gun sales were the cause, for four reasons.

First, this argument confuses stocks and flows. The flow of guns went up by about 50% over 2020. The stock of guns went up much less. Wikipedia says there are about 400 million guns in the US. That means that in 2019, when people bought about 14 million guns, the total number of guns was going up about 3.5% (and murder was low). In 2020, when people instead bought about 22 million guns, the total number of guns went up 5.5%, so about 2 percentage points more than in a normal year.

So this theory requires us to believe that number of guns increasing 3.5% every year from 2015 - 2020 had no effect on the murder rate, but that guns going up 5.5% in 2020 had a very strong effect on the murder rate. Specifically, an extra two percent increase in guns must lead to a 30% increase in murder rates. Why would we believe that?

One reason might be if the people buying guns in 2020 were very different from the people buying guns in previous years. For example, if previous gun buyers were collectors who had 100 guns each, but 2020 gun owners were new buyers getting their first gun, then the share of people with at least one gun would go up by more than 2% over an average year.

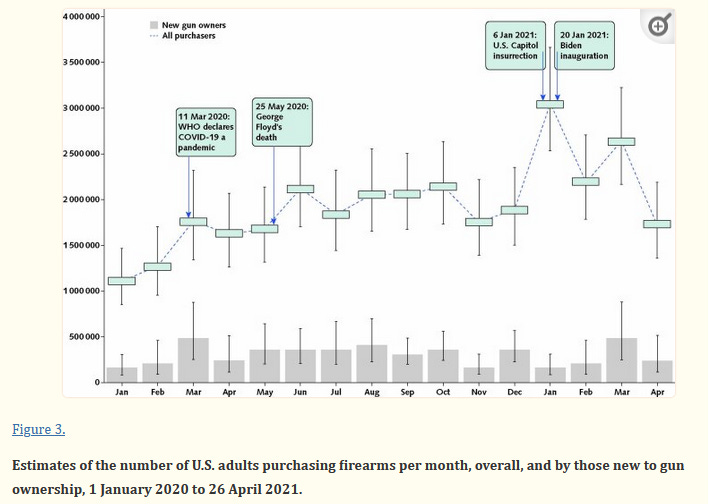

Miller, Zhang, and Azrael (2021) explores this question (thanks, darawk) and find the opposite:

The people buying new guns are mostly (~80%) people who have guns already. This varies a bit by time period but other periods (the beginning of the pandemic and the 1/6 insurrection) were more disproportionately new gun owners than the June period when homicides started to spike.

This also shows that the largest month-over-month increases in gun purchases, both new and total, were March 2020 and January 2021. There was no sudden homicide spike associated with either of these months, only May/June 2020.

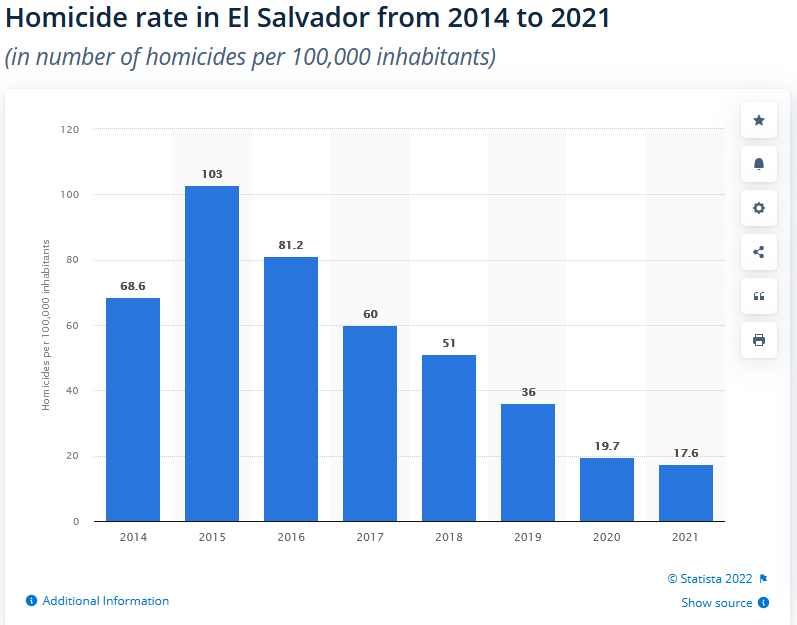

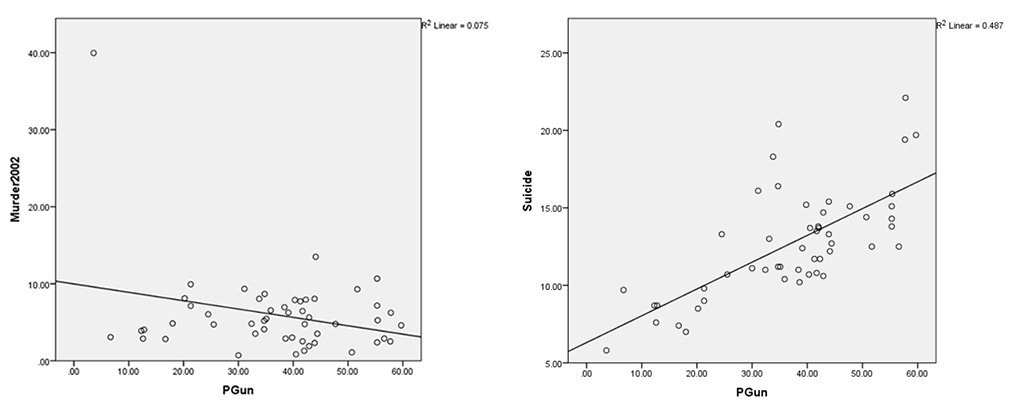

Finally, guns are usually more correlated with suicide deaths than with homicide deaths…

State by state correlation between gun ownership and murder rates (left), and between gun ownership and suicide rates (right). Source here.

State by state correlation between gun ownership and murder rates (left), and between gun ownership and suicide rates (right). Source here.

…but there was no spike in suicides at the same time as the murder spike:

This is what you’d expect given that the number of guns only increased by 2% over trend - a completely invisible effect on suicide. Unrelatedly, homicides rose by 30%.

So the gun hypothesis requires that:

-

Crime tracks the flow, rather than the stock, of guns.

-

…so a 2% increase in guns can cause a 30% increase in homicides.

-

…even when only a fifth of those guns are going to people who don’t have guns already.

-

For some reason, an earlier larger spike in gun purchases (March 2020) and a later larger spike in gun purchases (January 2021) failed to have any detectable effect on homicide rates, but the comparatively small spike in June 2020 immediately (ie within less than a week) caused homicide rates to rise 30%.

-

A secular 20-year tripling of yearly gun purchases also failed to affect the homicide rate, or was disguised by an exactly equal counter-trend.

-

Although usually rising gun ownership increases suicide somewhat more than homicide, this time and this time alone it increased only homicide.

None of this seems very plausible to me.

How Much Of A Racial Difference Was There?

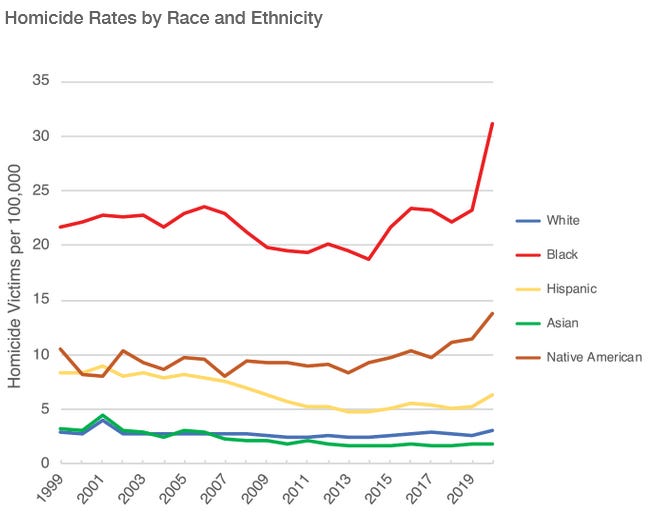

I had previously posted this graph:

…apparently showing a much larger spike in black compared to white homicide rates. But Artifex0 argued that because the black rate started so much higher, a similar relative change would look like a much bigger absolute one. He was able to track down the data and find that black homicide rate increased 33% and the white rate 22%. I think this is 2019 to 2020 data, which might mean that half of the 2020 data is before the homicide spike and it should be expected to minimize the differences by diluting them with 5 months of pre-spike data.

So I acknowledge that there was a rise in white homicide and that my original graph minimized that. But the rise in black homicide seems to have been at least 50%, and possible more, larger in magnitude. I think this fits the idea of police pulling back especially from predominantly black areas. There will be some white people in predominantly black areas, and police will also pull back from other areas that aren’t predominantly black.

Did The Spike Start Very Slightly Too Early?

Quincy writes:

Kind of feels like Scott came to his conclusion first and then is now reading the data to support that. But the data doesn’t at all look convincing to me. Clearly there was a spike around May, but the data shows it was starting in the middle of May? Floyd died on May 25, and while protests began the next day in Minneapolis, they really didn’t pick up steam across the country until a few days later. But, for example, the NYC chart shows a clear escalation that starts at the beginning of May.

My first thought was that this is a natural result of superimposing a shock on a random trend. For example:

The first image is some randomly varying trend. The second image shows (in red) some unusual shock in the trend, which we can see here starts around time 4. But since real events aren’t color-coded, we would just see the third image, where it looks like the shock starts around time 2.5.

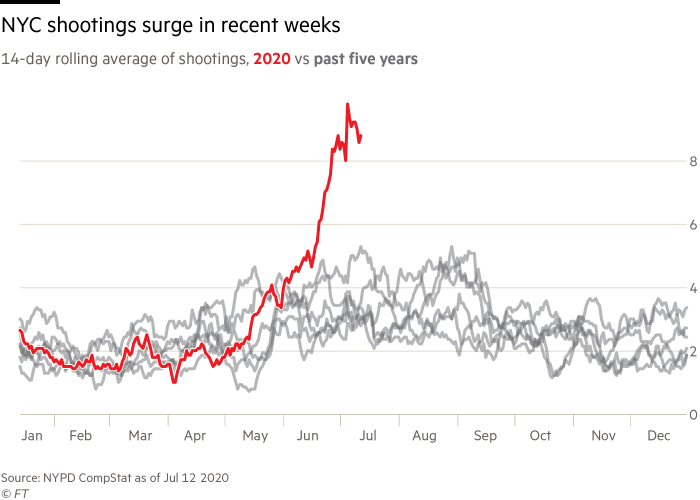

Here’s the NYC data Quincy was talking about:

I am not too impressed by the increase in early May. If you look at the gray lines, you can see it’s still well within normal variation - other years had equal or greater increases in early May. The first time the red line gets above the level that’s been reached in other years is in early June.

But maybe we don’t even need to deploy this argument! If you look at the image, it says “14 day rolling average of shootings”. Depending on how they calculate the rolling average, that could mean that shootings start showing up in the data a week before they actually happen (if they really calculated it a weird way, 14 days before they actually happen), which would amply explain the rise without having to bring in random variation at all.

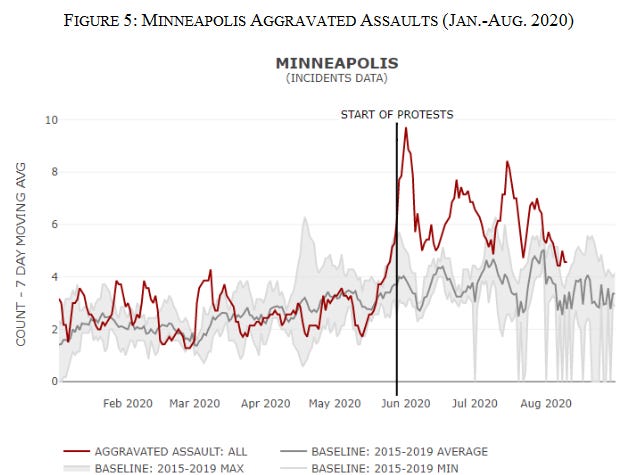

What about this Minneapolis graph?

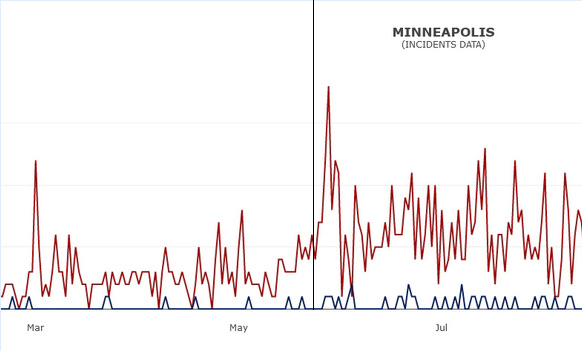

The site it comes from also uses a rolling average, but commenters tested it and find it’s retroactive; it moves events later in time rather than earlier. But here’s what you get when you un-rolling-average it.

The black line marks Floyd’s death. I don’t know, this still looks to me like Floyd’s death was the breakpoint and there’s not very much going on before that.

Also, what would be the explanation for why this trend would start on May 20 or something? There isn’t more pandemic that day. There aren’t more guns that day. It’s not even especially warm that day. I think it’s got to be an artifact.

What Exactly Are Police Doing Differently?

The post avoided getting into specifics here, but Graham writes:

For those who’d like coverage of the crime spike - specifically about why police pull back - without the annoying “own the libs” angle, I will do something I try not do here and recommend myself:

The Graham FactorHow depolicing happensRead more3 years ago · 35 likes · Graham

The Graham FactorWhy I’m cynical about police reformRead more2 years ago · 37 likes · Graham

Edit: A TLDR per request:

1. Police capacity is declining. Part of this is “defunding” and officers resigning, but part of it is the increased demand for statistics and reporting by “reform” advocates. For example, California requires all cops to fill out a Racial Identity and Profiling Act (RIPA) report every time they stop someone. When there are fewer cops and it takes longer to do basic police work, the volume of police work declines.

2. Police respond to changes in risk. Police are evaluated on whether what they do is “reasonable” - a rule which should allow for good-faith mistakes, but which is also subjective. When an officer who is fired or prosecuted for something that is clearly unreasonable (like Derek Chauvin, whom all cops agreed was guilty) police don’t worry about it. However the trend now is to prosecute officers even for things which are arguably unreasonable - Chesa Boudin just lost an excessive force case against a cop in San Francisco. If you can’t convince a San Francisco jury that a cop used excessive force, that case never should have been brought. Even when officers don’t end up in prison - nobody wants to end up the target of a massive media smear campaign, like the officer in the Jacob Blake case.

3. Many large cities and states are now making it very clear that they literally do not want police to do proactive police work. Philadelphia, for example, banned police from doing traffic stops. Baltimore’s prosecutor said she won’t prosecute any cases for drug possession. Boudin refused to use evidence San Francisco police gathered during “pretextual” traffic stops. When political leaders tell officers that they should stop doing police work, police stop doing it.

My second link above explains that these results are (in my opinion) a feature of police reform, not a bug. Summer 2020 was a mask-off moment, and the intellectual leaders of the “reform” movement in the ACLU and DOJ don’t actually want police “reform.” They want less policing, and that’s what they are now getting.

Graham also has a discussion of the legalities of the Derek Chauvin murder case. TL;DR: whether or not Floyd was on drugs or had pre-existing health problems, Chauvin’s actions qualified as felony assault and hastened Floyd’s death. In Minnesota, if you commit a felony that hastens someone’s death, that qualifies as felony murder, even if it was an “accident” or there were other contributing factors.

JPodmore writes:

There’s an alternative explanation that fits the evidence here: the killing of Floyd itself caused the crime increase by damaging trust in the police, which led to an increase in retaliatory violence.

https://www.city-journal.org/retaliatory-gang-violence

I posted some of this as a reply but it occurred to me that it might be worth elaborating on as a main comment. The police arbitrate violent disputes. If your friend is shot and the police to deal with it, there’s probably no further violence: the perpetrator is arrested and sent to prison, end of story. But if you don’t trust the police to deal with it - because there has been an extremely prominent example of them being untrustworthy - you might decide to take matters into your own hands and seek violent revenge.

This is just as compatible with the timing of the evidence you’ve described, including the pre-pandemic stuff in Baltimore and Ferguson.

I don’t really think of this as an alternative explanation. I am agnostic to the exact causal pathway between the events of May 25 2020 and the homicide spike; all I’m trying to show is that the spike did begin around that time and seems connected.

Did The Media Get This Right?

Matt Yglesias writes:

I agree with almost everything in this post except for the media criticism parts. The conclusions seem very similar to this January New York Times article, for example:

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/18/briefing/crime-surge-homicides-us.html

My sense is that (1) most people believe the spike in murders was related to the Floyd protests, (2) most people believe that because the theory has been widely aired in the media, (3) the people and the media are almost certainly right about this.

What’s much harder to say is exactly how the protests relate to the murder surge and what could we do about it?

The linked article says, in a sentence I would argue is as close to its thesis/conclusion as anything:

“All three [of the pandemic, the protests, and the rise in guns] played a role,” Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, told me. “What’s difficult is to assign priority to one compared to the others.”

My claim is that this is false. It is not difficult to assign priority. The protests were the primary cause, with the other two being minor contributors at most. When I say the media is getting this issue wrong, I mean that they’re saying things like this.

What Does The Literature Say?

KillerBee writes:

Scott, you are wrong (about the original Ferguson effect, which serves as a robustness check of your more general claim of protests -> homicides)! And I can show you why. Why should you read this random comment among a sea of meshugas? Argument from authority: I’m a PhD candidate in one of the top criminology programs. In other words, I’m intimately familiar with both the content area and the issues of time-series analyses. I’m happy to privately verify this and/or share full text articles I source below if they are paywalled. Key points:

0) Begging the question and also not citing relevant literature that tests+disproves your claims

Throughout this letter (which should be revised to become a mea culpa), you conflate two separate hypotheses:

a) There is a POSITIVE ferguson effect (aka protest effect) on DEPOLICING (aka less ‘active’ or ‘proactive’ policing)

b) There is a POSITIVE ferguson/protest effect on violent crime, PARTICULARLY HOMICIDE

Hypothesis A appears true: police do pull back from policing when facing public scrutiny. The extent of this pullback is debated. For more info, see MacDonald 2019; Marier and Fridell 2020; Mourtgos, Adams, and Nix 2022; Rosenfeld and Wallman 2019. However, you beg the question by showing hypothesis A is true, and claiming hypothesis B is also true!

Hypothesis B is plausible and worth exploring! This is because at the extremes both 1) more and/or well targeted police(ing) reduces crime (Evans and Owens 2007; Sherman 2022) and 2) poorly targeted and/or no police(ing) increases crime (Loeffler and Braga 2022; Piza and Conneally 2022). Deterrence - particularly versus nothing - does exist (Nagin 2013)!

However, the problem is that we have actually tested hypothesis B and found it lacking! See the Criminology and Public Policy Volume 18 Issue 1 (2019), particularly Rosenfeld and Wallman 2019. The issue is that there’s an assumption that arrests (and other CJS interventions) have a UNIFORM marginal effect, but this may not be the case. Instead, imagine that the marginal effects of incrementing/decrementing a(n) arrest/imprisonment/search/stop etc. is conditional on the cumulative exposure, much like a laffer curve! In this case, it is not so clear that reducing police interventions would result in increased crime, as long as the reduction isn’t ‘too large’. See Owens 2019 for a very good short summary on this economic perspective on CJS interventions.

So, TL;DR hypothesis A doesn’t mean hypothesis B, and in fact we (criminologists) have already done this work and found hypothesis B lacking.

There’s actually much more to the comment, and several followups, click the link for more.

The main study mentioned here is this one. I cannot follow all the mathematical details, but it does appear to show that the 2015 post Ferguson spike (not the more recent 2020 spike) doesn’t appear in the data as a city-by-city correlation between decreased arrest rates (as a proxy for depolicing) and rising homicide rates.

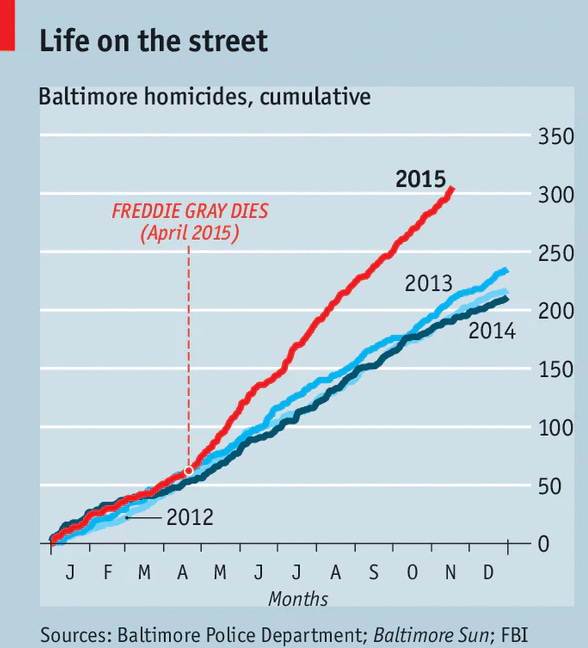

I think I would just reiterate what I said about a similar study in the post, which found no overall significant effect, but yes a significant effect when it limited the effect to a few large predominantly black cities with large protests. The data from eg Baltimore in particular:

…seem pretty hard to ignore. If many cities were like Baltimore, okay - but if the effect was limited to a small number of cities, such that it gets washed out in the national data and the clearly visible 2015 spike doesn’t reach statistical significance, that’s fine too.

(The particular way that arrests and homicides failed to be correlated here was that there wasn’t really a nationwide noticeable decrease in arrest rates after Ferguson and Baltimore. But there was a large decrease in arrest rates in Baltimore. So I think of this as showing that this particular shock wasn’t the main thing driving the relationship between arrest rates and homicides in US cities during that time)

I think KillerBee wants to think of this as testing a hypothesis about mechanism: was it changing arrest rates that changed the homicide rate? I would want to hear more from people who understand the math of the model before updating too hard on this, but I guess it’s some contrary data.

Was It Warm Weather?

Several people argued that maybe the pandemic naturally increased people’s murderousness, but that it took until there was warm weather for the effect to show up. For example, Alex Curtiss:

You cite the timing of the homicide spike vs the beginning of the pandemic many times, but that’s unconvincing to me. The beginning of the pandemic was characterized by widespread lockdowns and much less activity. It was also still pretty cold in many northern cities. As you said yourself, murder rates often spike with warmer weather–couldn’t the pandemic plus warmer weather potentially explain the timing? (And yes ALSO the protests?)

I have to admit, I find it hard to take this one seriously.

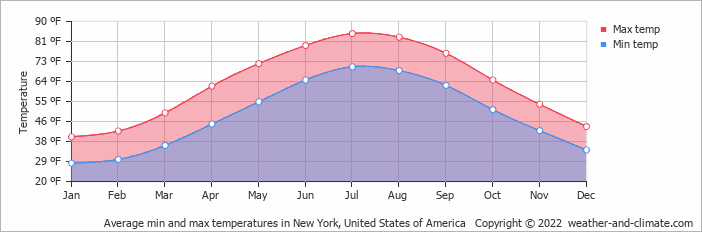

I can’t find temperatures for 2020 in particular, but here’s average temperature in New York City over the course of the year.

We would have to imagine that, as the pandemic started in March, nobody was committing extra pandemic murders, because of the temperature (they were still mostly committing their usual murders, though). As the temperature gradually rose through late March, April, and early May, murder did not rise at all above its historical baseline, because all the pandemic-dependent murderers were waiting for the temperature to hit some critical point. Then in late May, as soon as the temperature hit some critical point (78 degrees?) there was a large discontinuity with all previous years’ murder trends in a way that had never happened before. Then, as the temperature continued to rise into July and August, there was no further increase. Then, as the temperature declined into the winter months, there was no further decrease: all those murderers, having been activated by the key temperature of 78 degrees occurring once, remained in their new murderous form, no matter how cold it got. Mind you, this has never happened before in any other year, it’s just a feature of the pandemic x murder interaction. Which didn’t happen in any other country, even though those countries also had pandemics and temperatures.

Except it couldn’t be 78 degrees exactly, because the homicide spike started at the the same time in a lot of different cities with widely varying temperatures. Maybe the murderers were actually waiting for a key solar angle?

I guess I’m being a jerk now, but I do feel like there’s a sort of “fighting a rearguard attack against the evidence” here that I find tedious. I feel the same way about “it took a few months for people to get cabin fever from the pandemic” theories.

I don’t deny that heat or cabin fever could have been a secondary factor that eg played into why the protests were so large this time.

Even More Other Countries

Some people objected to my using three European countries (plus a nod at China) as my baseline. European countries seem pretty stable, maybe they wouldn’t show a pandemic-fueled rise in murders in the same way as the US.

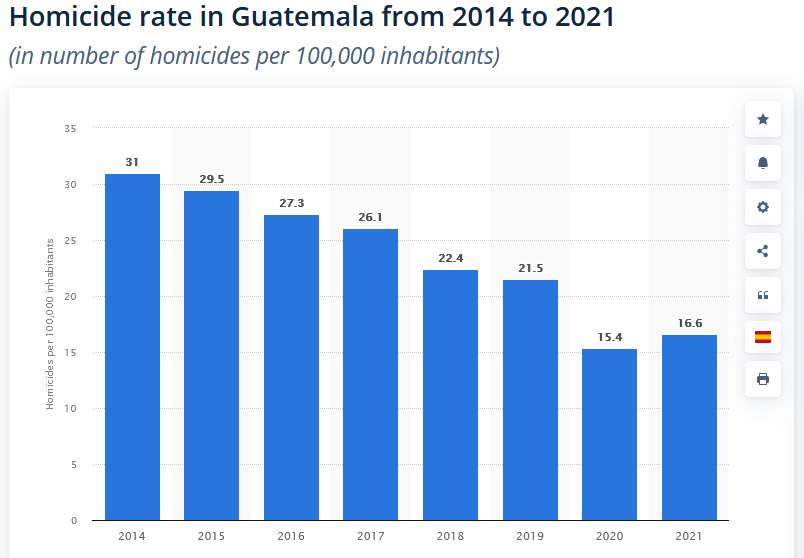

At commenters’ request, I looked at Central American countries. These usually have lots of guns, high murder rates, and poor social safety nets. Here they are (sources for Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala):

All four Central American countries I looked at had declines in homicides, rather than spikes, in 2020, despite also having pandemics and warm weather.

If you have some clever reason why Central America is also a bad comparison, then please find me any major country besides the US that had a homicide spike in 2020 (bonus points for May/June 2020 in particular). I’m not saying that one will convince me; in two hundred-odd countries there might be one that had a simultaneously-timed homicide spike just by coincidence. But it would be a start.