In Continued Defense Of Non-Frequentist Probabilities

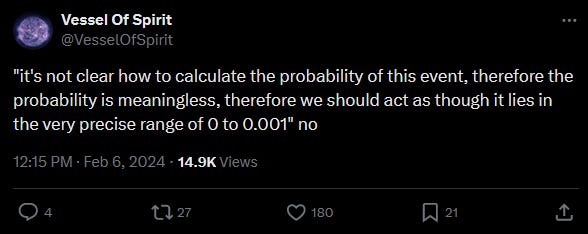

It’s every blogger’s curse to return to the same arguments again and again. Matt Yglesias has to keep writing “maybe we should do popular things instead of unpopular ones”, Freddie de Boer has to keep writing “the way culture depicts mental illness is bad”, and for whatever reason, I keep getting in fights about whether you can have probabilities for non-repeating, hard-to-model events. For example:

-

What is the probability that Joe Biden will win the 2024 election?

-

What is the probability that people will land on Mars before 2050?

-

What is the probability that AI will destroy humanity this century?

The argument against: usually we use probability to represent an outcome from some well-behaved distribution. For example, if there are 400 white balls and 600 black balls in an urn, the probability of pulling out a white ball is 40%. If you pulled out 100 balls, close to 40 of them would be white. You can literally pull out the balls and do the experiment.

In contrast, saying “there’s a 45% probability people will land on Mars before 2050” seems to come out of nowhere. How do you know? If you were to say “the probability humans will land on Mars is exactly 45.11782%”, you would sound like a loon. But how is saying that it’s 45% any better? With balls in an urn, the probability might very well be 45.11782%, and you can prove it. But with humanity landing on Mars, aren’t you just making this number up?

Since people on social media have been talking about this again, let’s go over it one more depressing, fruitless time.

1. Probabilities Are Linguistically Convenient

I think everyone agrees it’s meaningful and useful to say things like “Humanity probably won’t land on Mars before 2050”.

That is, suppose NASA and ESA and SpaceX hire a team of experts to calculate whether they can make it to Mars by 2050. They examine all the evidence and find that going to Mars is much harder than anyone thinks, all the rockets that people plan to use for the task are fatally flawed, and it would take decades to invent better ones. They don’t come up with a mathematical model or form a distribution, they just intuitively notice all these things, and how they add up. When giving her report, the leader of the team says “We don’t think humanity can land on Mars before 2050.” This person hasn’t done anything wrong - it’s impossible to communicate useful information without doing something like this.

How unlikely is it? Again, it seems like there might be different degrees of unlikelihood. For example, it might be that it’s pretty hard to make it to Mars by 2050, but with a strong effort and very good luck, we could manage it. Or it might be that it’s insane to even consider that we could make it to Mars by 2050, there are twenty unsolvable problems in the way and everyone who claims to be working on them is a total fraud. So probably the leader of the team should be allowed to say either “It’s pretty unlikely we can make it to Mars by 2050” or “It’s very unlikely we can make it to Mars by 2050.”

Suppose she says “it’s very unlikely”. We might still want to know more information. It’s “very unlikely” humans can make it to Pluto by 2050, and also “very unlikely” we can make it to the Andromeda Galaxy by 2050, but these seem like different levels of unlikeliness. You can sort of imagine a scenario where everything goes right and we make it to Pluto, but the Andromeda Galaxy would require totally new science that suspends apparently ironclad physical law. So maybe we need at least two levels of “very unlikely” - one corresponding to the likelihood of getting to Pluto, and one corresponding to the likelihood of getting to Andromeda. We could call these “very unlikely” and “extraordinarily unlikely bordering on impossible”.

How many terms like “slightly unlikely”, “very unlikely”, “extraordinarily unlikely”, etc do we need, and how will we make sure that everyone knows what they mean? It seems like having these terms is strictly worse than using a simple percent scale, where the leader of the Mars investigation team says “I think there’s about a 5% chance we can make it to Mars by 2050”. This is obviously clearer than “I think it’s unlikely” and prevents you from having to answer a bunch of followup questions. There are lots of people and space agencies who want to do different things if the chance of making it to Mars is 5% vs. 25%, and collapsing those both under “unlikely” or making people strain to figure out the meaning of “unlikely” vs. “very unlikely” and which one corresponds to 5% vs. 25% feels stupid, like deliberately introducing noise into your communication and asking people to solve a Twenty Questions game before they figure out your true opinion.

To put it differently, saying “likely” vs. “unlikely” gives you two options. Saying “very likely”, “somewhat likely”, “somewhat unlikely”, and “very likely” gives you four options. Giving an integer percent probability gives you 100 options. Sometimes having 100 options helps you speak more clearly.

A counterargument against doing this might be that it falsely introduces more precision than you can back up. But this isn’t true. Studies find that people who use probabilities often are well-calibrated - ie when they say something is 20% likely, it happens 20% of the time. Other studies find that when superforecasters give a very precise probability (like 23%) the extra digit adds information (ie the thing really does happen closer to 23% of the time than to 20% of the time).

In this case, demanding that people stop using probability and go back to saying things like “I think it’s moderately likely” is crippling their ability to communicate clearly for no reason.

2. Probabilities Don’t Describe Your Level Of Information, And Don’t Have To

Lots of people seem to think that naming a probability conveys something about how much information you have (eg “How can you say that about such a fuzzy and poorly-understood domain?”). Some people even demand that probabilities come with “meta-probabilities”, an abstruse philosophical concept that isn’t even well-defined outside of certain toy situations. I think it’s easy to prove that none of this is necessary. Consider the following:

-

What’s the probability that a fair coin comes up heads?

-

What’s the probability that a coin, which you suspect is biased but you’re not sure to which side, comes up heads?

-

Consider some object or process which might or might not be a coin - perhaps it’s a dice, or a roulette wheel, or a US presidential election. We divide its outcomes into two possible bins - evens vs. odds, reds vs. blacks, Democrats vs. Republicans - one of which I have arbitrarily designated “heads” and the other “tails” (you don’t get to know which side is which). It may or may not be fair. What’s the probability it comes out heads?

The answer to all of these is exactly the same - 50% - even though you have wildly different amounts of knowledge about each. This is because 50% isn’t a description of how much knowledge you have, it’s a description of the balance between different outcomes.

Is it bad that one term can mean both perfect information (as in 1) and total lack of information (as in 3)? No. This is no different from how we discuss things when we’re not using probability.

Do vaccines cause autism? No. Does drinking monkey blood cause autism? Also no. My evidence on the vaccines question is dozens of excellent studies, conducted so effectively that we’re as sure about this as we are about anything in biology. My evidence on the monkey blood question is that nobody’s ever proposed this and it would be weird if it were true. Still, it’s perfectly fine to say the single-word answer “no” to both of them to describe where I currently stand. If someone wants to know how much evidence/certainty is behind my “no”, they can ask, and I’ll tell them.

Likewise, is there a God? Maybe you ask the world’s top philosopher of religion, who has spent his entire life thinking about this question, and he says “I’m not sure”. Then you ask a random teenager who has given it two seconds’ thought, and she also says “I’m not sure”. Neither of these people has done anything wrong. Their identical answers conceal a vastly different amount of thought that’s gone into the question. But it’s your job to ask each person how much thought they put in, not the job of the English language to design a way of saying the words “I’m not sure” that communicates level of effort and expertise.

Likewise, if I answer there’s a 0.001% chance vaccines cause autism, and a 0.001% chance monkey blood causes autism, it’s not the job of probability theory to tell you how much effort went into that assessment and how much of an expert I am. If you care about that, you can ask me!

3. What Is Samotsvety Better Than You At?

Samotsvety Forecasting is a team of some of the top forecasters in the world. Their job is to assign probabilities to future events. They seem very good at it. They win forecasting contests. They make lots of money on prediction markets. They get featured in media articles. Sometimes people hire them as consultants when they have some forecasting question relevant to their business.

Sometimes some client will ask Samotsvety for a prediction relative to their business, for example whether Joe Biden will get impeached, and they will give a number like “it’s 17% likely that this thing will happen”. This number has some valuable properties:

-

It’s well-calibrated. Things that they assign 17% probability to will happen about 17% of the time. If you randomly change this number (eg round it to 20%, or invert it to 83%) you will be less well-calibrated.

-

It’s pretty close to what prediction markets, experts, and other superforecasters would independently converge on.

-

Whenever something happens that makes Joe Biden’s impeachment more likely, this number will go up, and vice versa for things that make his impeachment less likely, and most people will agree that the size of the update seems to track how much more or less likely impeachment is.

-

If you were someone whose job involved adjusting for situations like these - for example, an oil trader who thought that Joe Biden getting impeached would change oil prices - you would do better at your job, over the long run, by treating it as 17% likely that Joe Biden would be impeached then by guessing randomly, or consistently taking some number 5% higher than Samotsvety’s number, or using some other method. If there were two oil companies, and one consistently used Samotsvety’s numbers to make decisions, and the other consistently took a random number 1-100 and made decisions with that, the one that used Samotsvety’s numbers would do better.

In other words, there’s something special about the number 17% on this question. It has properties that other numbers like 38% or 99.9999% don’t have. If someone asked you (rather than Samotsvety) for this number, you would give a less good number that didn’t have these special properties. If by some chance you actually were better at finding these kinds of numbers than Samotsvety, you could probably get a job as a forecasting consultant. Or you could make lots of play money on Manifold, or lots of real money on the stock market, or help your preferred political party as a campaign strategist.

The search for these special numbers seems to be socially valuable. At the very least, hedge funds would pay quite a bit of money for someone who could come up with a special number that worked even better than Samotsvety’s. Also, if Samotsvety’s number for a question like “will your hometown be nuked in the next hour” ever reached 99.999%, you would really want to know this.

I think the best way to describe this kind of special number is “it’s the chance of the thing happening”, for example, the chance that Joe Biden will be impeached.

The only reason not to do this is some sort of metaphysical objection. “Yes, this number behaves in every way as if it were the chance that Joe Biden will be impeached, and you should treat it as the chance that Joe Biden will be impeached, and you can benefit from thinking of it as the chance that Joe Biden will be impeached - but on a metaphysical level, it’s not the chance that Joe Biden will be impeached. It’s a different kind of thing that we have no name for.”

I don’t understand why you would want to do this. If you do, then fine, let’s call it shmrobability. My shmrobability that Joe Biden will be impeached is 17%, my shmrobability that humans will land on Mars before 2050 is 66%, and my shmrobability that AI will destroy all humans before 2100 is 20%, and you should treat all of these exactly like probability estimates, even though they aren’t.

4. Do People Use Probability “As A Substitute For Reasoning”?

This is one of the claims going around on social media right now, somehow.

A probability is the output of a reasoning process. For example, you might think about something for hundreds of hours, make models, consider all the different arguments, and then decide it’s extremely unlikely, maybe only 1%. Then you would say “my probability of this happening is 1%”.

Sometimes this reasoning process is very weak. You might have never thought about something before, but when someone demands an answer, you say “I don’t know, seems unlikely, maybe 1%”. This claim neither demands nor posits more evidence than just “I don’t know, seems unlikely”. Nobody would claim that saying “This seems unlikely” is a substitute for reasoning.

Sometimes this reasoning process is formal, like when you create a model and calculate it out. Other times it’s informal, like when you think really hard about the case for and against something. There’s nothing wrong with informal reasoning. In fact, since there’s more than one possible model to apply to each problem, people have to use informal reasoning to figure out how much they trust each model and where their final answer lands. All answers, whether they’re “I’m sure this is true” or “I give this 75% probability”, are the product of formal reasoning filtered through informal reasoning.

Some people get really mad if you mention that Yoshua Bengio said the probability of AI causing a global catastrophe is 20%. They might say “I have this whole argument for why it’s much lower, how dare you respond to an argument with a probability!” This is a type error. Saying “Yoshua Bengio’s p(doom) is 20%” is the same type as saying “Climatologists believe global warming is real”. If someone gives some long complicated argument against global warming, it’s perfectly fine to respond with “Okay, but climatologists have said global warming is definitely real, so I think you’re missing something”. That’s not an argument. It’s a pointer to the fact that climatologists have lots of arguments; the fact that these arguments have convinced climatologists (who are domain experts) ought to be convincing to you. If you want to know why the climatologists think this, read their papers. Likewise, if you want to find out why Yosuha Bengio thinks there’s 20% chance of AI catastrophe, you should read his blog, or the papers he’s written, or listen to any of the interviews he’s given on the subject - not just say “Ha ha, some dumb people think probabilities are a substitute for thinking!”

A claim “this knowledgeable scientist has a probability of X” is a statement of the same type as “this knowledgeable scientist believes X”. A claim “ordinary people have a probability of X” is of the same type as “ordinary people believe X”. I don’t care super hard what ordinary people believe about whether global warming is true. But giving their probabilities rather than their binary answers doesn’t make me care less.

The only case where probabilities might take a different type than a normal binary answer is when people try to do wisdom-of-crowds with them. I think this is justified by the fact that wisdom of crowds works very well. But I don’t think this is what people are complaining about.

5. Is AI Even More Unmodelable Than Mars Landings Or Politics?

A remaining objection: we at least know, sort of, how rockets work. We at least know who controls Congress and what impeachment is and approximately what kind of guy Joe Biden is. So we have some starting point for modeling these questions. We barely know anything about the future of AI. So even if you can come up with a probability of Joe Biden’s impeachment, probabilities about the future of AI are bunk.

I agree that, because of the thorniness of the question, probabilities about AI are more lightly held than probabilities about Mars or impeachment (which in turn are more lightly held than the weatherman’s probability about whether it will rain tomorrow, which in turn is more lightly held than probabilities about coin flips). But I think the best way to represent your lightly held opinion is with a probability.

If you actually had zero knowledge about whether AI was capable of destroying the world, your probability should be 50%. If you object to this claim - like most people do! - that’s because you actually know quite a lot of things. For example, you know that most technologies don’t destroy the world, and in fact the world has gone eons without being destroyed. That alone should give you a low prior that AI destroys the world. But AI is probably more likely to destroy the world than, eg, a new way of cracking walnuts is, so you can’t get your prior exactly by counting up the number of technologies and considering AI a typical member of the set.

So given all the things you know - like the rarity of the world being destroyed, but the fact that some people have some stories about how it might happen for AI - and all the things you don’t know, where do you land?

If you land at some specific point, then naming that point isn’t a claim to be a smart expert who has lots of information. It’s just weighing the various arguments for and against it happening, and landing at “yeah, seems kind of likely” or “no, this seems crazy”. Except instead of using vague words, you use a non-vague system of 100 words which can be easily compared to the points where other people landed.

Nobody knows anything for sure about human extinction from AI, but some people, like Yoshua Bengio and Sam Altman, have more information than usual, or have thought about it a lot. It seems useful for them to be able to convey the results of their thinking to the rest of us. If you ban them from using probability because of some kind of metaphysical objection, you’re just forcing them to to say unclear things like “well, it’s a little likely, but not super likely, but not . . . no! back up! More likely than that!”, and confusing everyone for no possible gain.