Information Markets, Decision Markets, Attention Markets, Action Markets

[thumbnail image credit: excellent nature photographer Eco Suparman, which is a great name for an excellent nature photographer!]

Information Markets

Niels Bohr supposedly said that “prediction is very difficult, especially about the future”. So why not predict the past and present instead?

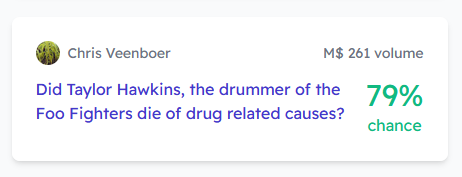

Here’s a recent market on Manifold (click image for link). Taylor Hawkins is a famous drummer who died last weekend under unclear circumstances. This market asks if he died of drug-related causes. Presumably someone will do an autopsy or investigation soon, and Chris will resolve the market based on that information. This is a totally standard prediction market, except that it’s technically about interpreting past events.

Same idea, only more tenuous. We know someone will do an autopsy on Taylor Hawkins soon, and we probably trust it. But how do we figure out whether COVID originated in a lab? This question’s hack is to ask whether two public health agencies will claim it. If we trust the public health agencies, we can turn this mysterious past event into a forecasting question.

But this is a strong ask. Even if we don’t specifically distrust the agencies, this question is a combination of “did COVID originate in a lab?” and “how likely are public health agencies to claim this?”. I expect the question would have a different prediction if it asked about “one public health agency” or “five public health agencies” or “China’s public health agency” or “the public health agency during a hypothetical second Trump administration” or “before the end of 2030”. All of that means we can’t interpret the prediction literally as being about whether COVID originated in a lab.

What will I (Scott Alexander) rate as most promising when I do a deep dive into the research on pregnancy interventions? Here you don’t have to trust public health agencies, you just have to trust me. Most people betting on this read my blog, which means they probably trust me at least a little. And I have no reason to lie about pregnancy interventions. So here the trust might actually be a fair assumption.

(though we still need an assumption that the research literature itself is correct and complete - this market substitutes for me doing the deep dive, not for scientists doing studies)

The first problem: I’ve gotten most of the way through this research, and the market is wrong. I’m not going to comment on whether the exact top guess is right or wrong, since that would interfere with people’s betting. But in general , some interventions I will place near the bottom are near the top, or vice versa.

In retrospect this isn’t surprising: most people on this market are playing for a 2-3 digit sum of play money. That’s not going to incentivize anyone to do 20 hours of research, or pay for an expert consultation, or anything else that would help them really understand this. They’re just pattern-matching to stuff they kind of heard, and maybe doing a few minutes of research to fill in gaps. I believe if this was a market for 5 or 6 digits of real money, it would go a little better, but so far that’s beyond us.

(when I was a poor medical student, Zvi Mowshowitz’s company ran a contest for the best literature review of mineral supplementation with a $5000 prize. I put in 20 hours of research and won. If I’m typical, this is proof of concept that big enough bounties can incentivize poor medical students to do good lit reviews)

The second problem: even if markets like these always worked, I would still have to do the literature review (to resolve the market). So this isn’t actually saving me any work!

The agreed-on solution for this is lots of conditional prediction markets. “If Scott did a review on pregnancy interventions, what would he find?” — “If Scott did a review on cholesterol medications, what would he find?” — “If Scott did a review on…”. Then I do one review, chosen randomly, resolve that market, and give everyone else their money back. I’ve learned about lots of topics for the price of doing research on one.

The only case I know of people already using this technique is replication markets, where people bet on which studies will replicate. You might, for example, set up markets on 100 studies, then actually conduct 10. The people who bet on those studies gain or lose money, the people who bet on the other 90 get their money refunded. These seem to work pretty well, though I’ve heard some claims and counter-claims about exactly how.

I once joked that instead of lower courts, we should have prediction markets on what the Supreme Court would think of a given case. Same idea, higher stakes.

Decision Markets

A very slight twist on information markets, eg:

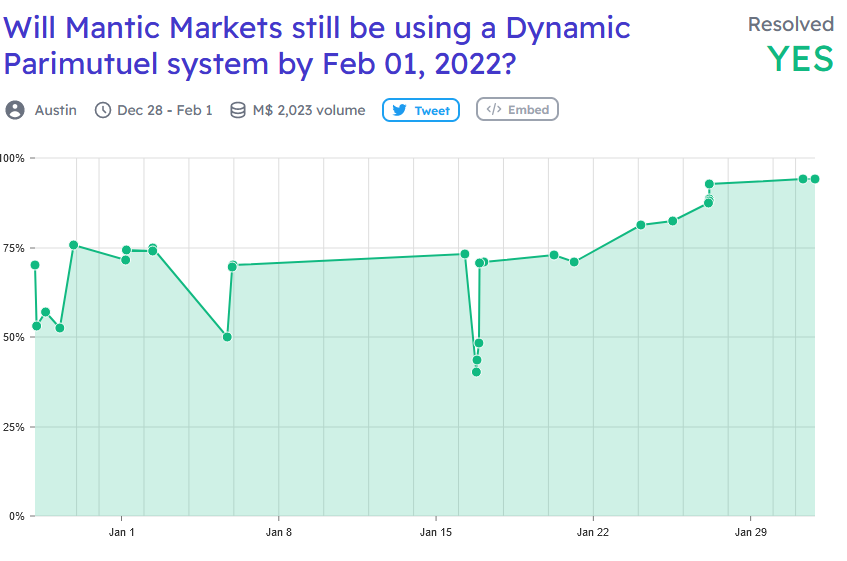

Austin, a co-founder of Manifold Markets (formerly Mantic Markets) asks the market what he’ll decide on this technical question. This does two things:

First, it encourages everyone who has a point for or against to try their best to convince him of it. If I know a knock-down incontrovertible reason for why dynamic parimutuel systems can never work, I can put all my money on “NO” and then tell Austin about it. Even if I only know a relatively weak consideration that I think other people have missed, I can short it a little and then tell Austin my weak consideration.

Second, it’s probably a pretty good guide to Austin whether he should actually use the system or not. Suppose you saw a bunch of the top experts in betting systems move the market to 99%. Seems like a strong argument.

But this has the same two problems as the information markets above.

The first problem: it only works if you trust Austin. The good news here is that Austin made this market, to advise Austin in making the decision, and presumably Austin trusts Austin. The bad news is that if everyone knows Austin is dumb and stubborn, they might bet on “YES” even if they know really good reasons to switch away from the parimutuel system. So at best this can just save Austin time; it can’t overcome his inherent limitations as an evaluator of evidence (unless investors don’t know about his inherent limitations, in which case I guess it can).

The second problem is: it can’t actually save him time. Austin still has to make the decision in order to resolve the markets. At best it can leverage his time, using the same method we discussed with information markets above.

(In theory, if Austin didn’t resolve the market, and everyone knew he wouldn’t, but there wasn’t common knowledge of this, it might end up as some sort of Keynesian beauty contest with the right answer as the Schelling point. But I wouldn’t want to test this, and I would expect it to break down pretty quickly).

Attention Markets

Here’s a different take on the same idea:

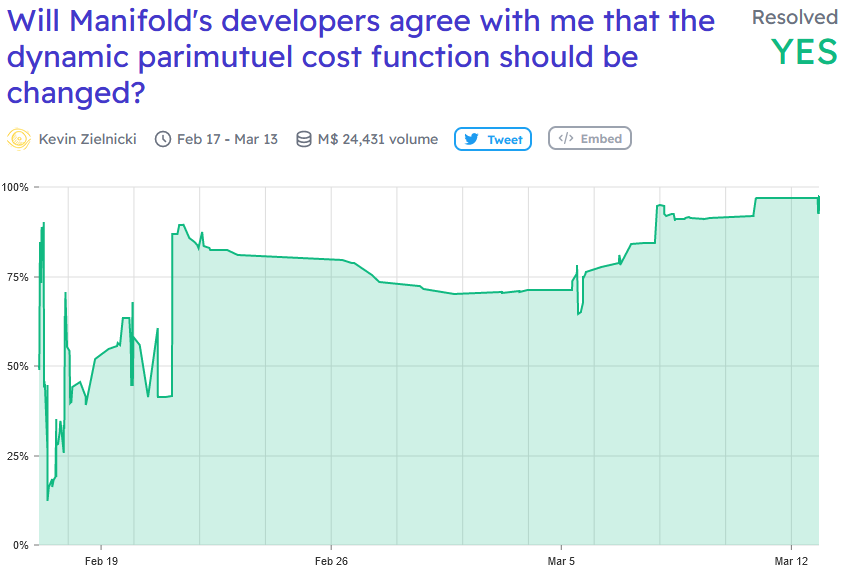

Unlike Austin, Kevin is not a co-founder or employee at Manifold. He’s just some guy who looked at their betting system and thought it had a flaw. Suppose the developers are really busy and don’t have time to listen to everybody’s complaints about their betting system. How can Kevin get their attention?

In this market, he asks: if the developers put in enough work to understand his complicated technical objection, would they agree it was valid? Investors agreed that they would, he (presumably) showed the Manifold team this prediction market saying there was a really high chance if they investigated this flaw they would be concerned about it, they investigated the flaw, and they agreed they were concerned and would work on changing it. The market resolved to “yes”.

The problem this addresses is common: ordinary people want decision-makers to take the time to understand their arguments that the decision-makers are doing something wrong. But the decision-makers don’t want to read through a hundred rants by people who mostly don’t know what they’re talking about.

Think of eg physics crackpots sending their manifestos to Scott Aaronson. After a while, Aaronson gets tired of reading every manifesto in detail. If there could be a prediction market for whether Aaronson would agree the manifesto contained a revolutionary insight, Aaronson could only read the ones that scored above some bar.

Problem: don’t the crackpots send their manifestos to Aaronson because he is one of the very rare people who know enough physics to recognize a fellow genius? And wouldn’t the investors on the market either be non-geniuses (in which case they’re not qualified to judge) or geniuses (in which case their time is as valuable as Aaronson’s and we’re not gaining anything by delegating from him to them)? I think that lots of non-geniuses can tell crackpot manifestos that might be true from ones that have no chance of being true, and all we need is some kind of probabilistic signal here.

Here’s an example of me using this strategy without requiring anyone to be a genius:

…but I still haven’t gotten any takers.

The biggest risk is that the decision-maker won’t be harsh and honest enough to admit when things aren’t worth their attention. Suppose I started an attention market for myself, and it escalated an appeal from a charity to help Third World orphans. I throw these out all unread the time when I get them in the mail, which seems like a strong signal that it’s not worth my time. But do I really want to publicly say the equivalent of “Stop wasting my time with this garbage” in a way that financially penalizes the people who bet I would want to see it?

Action Markets

Everyone’s favorite question about prediction markets: don’t they incentivize you to assassinate people?

That is, suppose there’s a market on whether Joe Biden will finish his term. Maybe it’s at 95% right now. If you bet “no” and assassinated him, you could 20x your money.

(you could also increase your money by 1.05x by doing a really good job protecting him, but that sounds harder and less lucrative)

The answer is: yes, this could happen.

But we should expect it to be very rare! Consider: couldn’t you make a lot of money right now by shorting Tesla and then assassinating Elon Musk? Or by shorting Boeing and bombing a plane? Or by going long on train companies, and bombing a plane? Or by going long on diamonds, and then bombing a diamond mine? Or by shorting Bitcoin, and lobbying for more punitive crypto regulations?

Every investment is also an action market! In general, we control this tendency through normal criminal laws. People don’t assassinate Elon Musk because then they’d be investigated for murder. Even if they manage to avoid leaving any fingerprints or whatever, police would probably still go after the guy who put all of his money into Tesla shorts the day before.

Still, as long as everyone knows what’s going on and no laws are being broken, fine, let’s have action markets:

This is my local rationalist group house. They’re betting on whether someone will clean up the (currently disastrous) backyard. They’ve said pretty openly that they’re hoping someone will buy a lot of “yes”, take care of the backyard project, and then take all their money. You can think of this as a weird bounty system.

But it’s strictly worse than a regular bounty system. For one thing, if I suspect someone else will take care of the backyard, then just by registering that prediction I can share the winnings with them, even though I didn’t do any work (since this is at 70% instead of 100%, someone must be doing something like this). For another thing, it incentivizes people to bet “no” and then sabotage cleanup projects.

I don’t think there’s any site as convenient as Mantic that lets people set perfectly normal bounties on things (should there be?) but a prediction market clearly isn’t the ideal tool here.

Is there any case when an action market might be better than a bounty?

Imagine I have a painful disease. Every year, there’s a 25% chance it goes away on its own, but I’d like to speed up the process. Lots of doctors want to try very expensive treatments on me, but I’m worried some of them are quacks.

If I hire one of the doctors and hope for the best, maybe he’s a quack and I’ve wasted my money.

If I hire one of the doctors, but make payment conditional on me being cured afterwards, there’s a 25% chance I’ll recover on my own and pay the doctor even though they were a quack.

If I hire a doctor, make payment conditional on me being cured, and make him pay me if I’m not cured, then a real doctor whose treatments work less than 100% of the time might decide to pass.

I think you could solve this problem by subsidizing a prediction market at 25% chance of recovery, and letting doctors bet on other odds. This would still have some problems - if someone saw a famous doctor betting, they could bet too, and “steal” some of the “winnings” from the doctor - but it seems to be kind of the right idea.

(could a doctor short the market, then kill you? Yes, but you could just not hire any doctor you saw shorting the market)

On this List Of Fictional Cryptocurrencies, I wrote about ConTracked:

ConTracked: A proposed replacement for government contracting. For example, the state might issue a billion ConTracked tokens which have a base value of zero unless a decentralized court agrees that a bridge meeting certain specifications has been built over a certain river, in which case their value goes to $1 each. The state auctions its tokens to the highest bidder, presumably a bridge-building company. If the company builds the bridge, their tokens are worth $1 billion and they probably make a nice profit; if not, they might resell the tokens (at a heavily discounted price) to some other bridge-building company. If nobody builds the bridge, the government makes a tidy profit off the token sale and tries again. The goal is that instead of the government having to decide on a contractor (and probably get ripped off), it can let the market decide and put the risk entirely on the buyer.

Banned because Wall Street developed a financial instrument that let them short ConTrackeds, then tried really hard to prevent bridges from being built.

Commenters brought up that you get weird incentives as soon as more than one person owns ConTrackeds, which I agree with. I’m still not sure there are clear real-world uses for action markets.

But they’re still fun to think about. In particular, “every prediction market is also an action market, and vice versa” is a useful law to keep in mind. Different prediction markets “leak” into being action markets at a different rate: one about when a distant star will supernova is 100% prediction; one about when a President will die is 99% prediction; one about when the forecasters’ backyard will be cleaned is maybe 80% action.

This idea comes up in some weird places. I’ve seen it in AI safety: AIs that you “only” ask to predict an event for you aren’t necessarily safe, partly because one easy way to predict an event is to cause it.

But my favorite example is from neuroscience. The “active inference” hypothesis - a leading theories of how brain motor centers work - says that the brain is entirely a predictive organ, but that the easiest way to predict your body position is to cause it. The brain registers a prediction of 100% that your arm will move, and then - in order to “win” its “bet” - moves your arm. “Every prediction market is also an action market”, indeed!