Is There An Illusion Of Moral Decline?

[Epistemic status: very uncertain about Part II; more convinced about Part III]

I.

This is the big question in the paper du jour , The Illusion Of Moral Decline , by Mastroianni and Gilbert (from here on: MG).

It goes like this: people say that morality is declining. We know this because one million polls have asked people “do you think morality is declining?” and people always answer yes. MG go over these one million polls, do statistics to them, and find that people definitely think that morality is declining. People have thought this since at least 1949, when the first good polls were run - but realistically much longer.

This could be (they say) either because morality is actually declining, or because of a bias. They argue that morality is not actually declining. In support, they marshal many polls asking questions like “Do you think most people are honest?” or “Do you think people treat you with respect?” and find that the answers mostly stay the same. Might this be because of definition creep - eg might people define “honest” relative to expectations, and expectations lower as morality declines? In order to rule this out, MG look at various objective questions that they think bear on morality, like “have you been mugged/assaulted recently?” or “have you donated blood in the past year?” They find that all of these have also stayed the same. Therefore, both people’s subjective impressions of morality, and more objective proxies for social morality, have stayed the same. Therefore, morality is not actually declining. Therefore there must be a bias.

MG suggest two biases that might create this illusion. First, people are better at remembering positive than negative events, so they might remember disproportionately good things about the past. Second, people are better at attending to negative events in general, and maybe this negatively biases their assessment of the present.

Speaking of biases, I’ll be honest - I’m biased against this study.

I’m biased against the introduction, where they pull the old trick of starting with a quote on how society is falling apart, then revealing it was from Livy writing in the first-century Roman Empire. They expect us to be shocked, as if every essay on moral decline hasn’t used the same flourish since - well, since the first-century Roman Empire.

I’m biased against the conclusion, which is “therefore, conservatives are wrong, so we should refocus from their fake fears onto the problems liberals care about” (think I’m strawmanning? Read the last paragraph of the Discussion section)

But I’m especially biased because I’ve been reading the biases and heuristics literature for fifteen years now, and developed the following heuristic: if a researcher finds that ordinary people are biased about how many marshmallows to take in a rigged experiment, this is probably an interesting and productive line of research. But if a researcher finds that ordinary people are biased about their most foundational real-life beliefs, probably those ordinary people are being completely sensible, and it’s the researcher who’s trying to shoehorn their reasoning into some mode it was never intended to address. And this study addresses some pretty foundational beliefs!

But aside from all these biases - wait, they found that the same number of people said they were mugged/assaulted recently in 1949 as today? Hasn’t violent crime approximately tripled since then?

II.

I think their measures of “objective morality” are not very good. Their evidence that morality has actually stayed the same over time is proof by exhaustion - a giant pile of hundreds of polls nobody wants to sort through - without much work to show that these polls bear on the question. Four issues are particularly concerning: timescale, accuracy, measurement, and sensitivity.

_Timescale: _The paper claims to be measuring this effect since 1949, but this only applies to subjective perceptions of decline. Their measurements of “objective” morality don’t go back nearly as far. Only one of their hundred-odd polls goes back as far as the 1960s; three more are from the 1970s1. The overwhelming majority analyze the period 2000 - 2015.

But when people say “there was more morality back in the good old days”, they rarely mean “in 2000 compared to 2015”. Even if moral decline were constant and linear, 2000 - 2015 might be too short a period for ordinary people to notice the difference.

If the few ‘60s and ‘70s polls were good, this might provide proof of concept that the same trends detected there were continuing through the 2000 - 2015 period. But the ‘60s and ‘70s polls are not good.

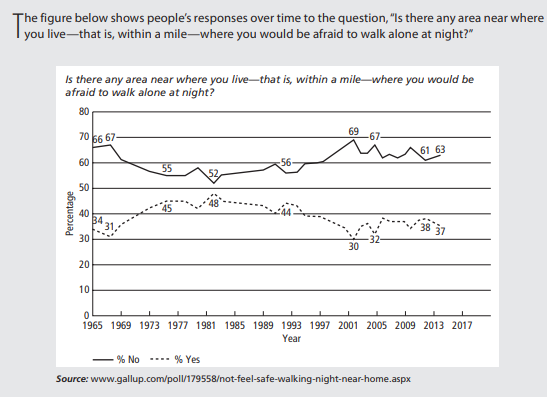

Accuracy: The lone “objective” polling series which goes back to the ‘60s is “Is there any area near where you live – that is, within a mile – where you would be afraid to walk alone at night?” I think it’s the same question represented here, which looks like this:

The graph agrees that the difference between the 1960s and today is 34% vs. 37%, ie pretty trivial.

But the crime rate data shows about 2.5x more violent crime today (source)2:

So using polls about whether people feel safe as a proxy for violent crime doesn’t work.

Part of this could be because people’s feelings are unmoored from reality. But also, when violent crime increased in the 70s, many people responded by fleeing to the suburbs. In the 60s, in the city center, they felt comfortable walking alone at night. Now, in the suburbs, still they feel comfortable walking alone at night. The crime rate is different, but the poll answers haven’t changed.

But not only are polls a bad proxy for violent crime, violent crime is a bad proxy for morality.

The incarceration rate today is 3-4x that of the 1960s; part of this is because punishments are stricter (eg “three strikes” laws). This artificially lowers violent crime rates; would-be violent criminals are stuck in jail, unable to re-offend. If moral fiber is declining, the justice system might pick up the slack, causing the decline to be represented in more prison rather than more victimization. See eg Friedman’s thermostat.

This is the only metric of “objective” moral fiber MG include that goes back more than fifty years, it’s a proxy of a proxy, and the non-proxy data tell the opposite story.

Measurement: There are three questions from the 1970s. One is a question about crime similar to the one above. Two others involve social trust. Let’s look at the second one: you can find a good graphical presentation here:

The graph seems pretty concerning. It shows that the percent of people who find others trustworthy has gone down from about 45% to about 30% over ~50 years. At this rate, in another century or so 0% of people will consider other people trustworthy. This doesn’t look like no moral decline. This looks like precipitous and concerning moral decline! And remember, I’m not cherry-picking: this is one of only two non-crime questions they have going this far back (the other also shows a decline, though less pronounced).

So how did they conclude that these kinds of questions imply no moral decline? I’m not sure. They describe their statistical methodology as:

The results of both analyses were clear: people’s reports of the current morality of their contemporaries were stable over time. On average, the year in which the survey was conducted explained less than 0.3% of the variance in responses, and in almost all cases it explained less than 1% (Supplementary Table 4). This result was confirmed by Bayesian analysis, which showed that 100% of the HDI was within the ROPE in all but one case, indicating that any changes over time were negligible at best.

I’m not a statistician and I can’t say for sure what these mean. But I think “the year in which the survey was conducted explained less than 0.3% of the variance in responses” is a statement about r^2 statistics. The r^2 statistic of the graph above is listed as “.008”. I think (not at all sure!) that this means “the year of the survey explained only 0.8% of the variance in responses”. That sounds tiny. But looking at the graph, the effect looks big. I would file this under “talking about percent variance explained is a known way to make effects sound small”, although I’m not sure about this and I welcome criticism from someone more statistically-literate.

Likewise, I don’t know what “100% of the HDI was within the ROPE” means, but I know they say it was true of the graph above, meaning they classify the graph above as showing “negligible change over time”. This seems concerning and wrong to me. I’m not an expert on these measures, I could be misunderstanding all of this, and it’s more of a question mark than an accusation; still, it concerns me.

Sensitivity: Crime and trust are pretty relevant, and 1960 or 1970 is a while back, so these are the kinds of questions which, if done correctly, might have been interesting. But many others seem more specific or limited.

For example, there are a bunch of polls like:

-

Compared to the past, have things gotten better, worse or stayed the same [regarding] treating Hispanics with respect and courtesy? (2002 vs. 2013)

-

Compared to the past, have things gotten better, worse or stayed the same [regarding] treating gay people with respect and courtesy? (2002 vs. 2013)

-

Compared to the past, have things gotten better, worse or stayed the same [regarding] treating African-Americans with respect and courtesy? (2002 vs. 2013)

Not only are these very specific, but remember, MG’s conclusion is that morality has not really changed since 1949. But clearly we have started treated African-Americans better since then. Shouldn’t their methods be able to pick this up?

They mention in the text that these kinds of questions did better than others; 50% report improved treatment of gay people. But what are the other 50% thinking??! The answer has to be something like “2002 to 2013 is too short a time to measure even extremely large effects that were centered around exactly this period”. But then what does that mean for the rest of their data?

Despite these questions, they report no change overall in morality. Is this because their methods are too weak to notice not just the improvement in gay rights over the early 2000s, but even the improvement in African-Americans’ condition since the 1950s? Or is it because these moral improvements have been counterbalanced by other moral declines since then for net zero gain? Either way this doesn’t reflect well on their thesis.

I think MG were most interested in talking about potential biases that could cause an illusion of moral decline. In order to get there, they had to argue that there was no objective moral decline, but they thought this was obviously true, and were more interested in gesturing at it than really proving it. They threw together a mountain of polls vaguely related to the topic, but I don’t think they’re really able to defend those polls’ relevance to this question against sustained challenge.

III.

So am I claiming that morality is declining over time?

A real answer to this question would require philosophical groundwork that this paper doesn’t even begin. Whatever the issues with the data, they’re the least of MG’s problems3. They’ve committed themselves to haphazardly combining polls on violent crime, blood donation, homophobia, volunteerism, and workplace abuse into a single construct, “morality”, and then making sweeping pronouncements about it.

“So the problem is they’re mixing up too many things?” No, they’re still mixing up too few things.

In all the hundred-ish polls that MG used as objective morality indicators, I counted zero that involved sex, marriage, divorce, child-rearing, drugs, alcohol, loyalty, patriotism, respect for elders, hard work, laziness, religion, or anything about God.4

Suppose you were born in 1940. You learned from your parents that morality was about going to church, staying chaste until marriage, loving your country, working hard, and staying away from drugs.

You notice that between 1940 and 2020:

-

Church membership declined from 75% → 50%

-

Premarital sex rate went from from 20% → 75%

-

Trust in government went from 75% → 20%

-

Prime-age-male-labor-force nonparticipation rate quadrupled from 3% → 12%

-

Marijuana use went from 4% → 49%

You describe this state of affairs as “I’m worried about a moral decline”. Then some psychologists pounce on you with one million graphs showing that actually we respect Hispanics as much as ever which means you’re just biased.

So an alternative explanation for widespread perception of moral decline is that each generation observes moral decline relative to its own standards. If you were born in 1940, you absorbed 1940 morality. The year 2020 does worse at 1940 morality than the year 1940 did, because the year 2020 isn’t trying to achieve 1940 morality, it’s trying to achieve 2020 morality, which is only partly correlated5.

This neatly explains MG’s finding that everyone believes morality peaked around the year of their birth and has been declining ever since. In fact, it explains the data better than MG’s own hypothesis: they find a marginal trend for people to rate morality worse 40 years before their birth than 20, which doesn’t fit a rose-colored glasses effect but does fit an imprint-on-your-own-birth-year one.

And this is part of why I find the introductory quote by Livy so annoying. What was morality to Livy? Respecting the lares and penates. Performing the ancestral rites. Chastity until marriage, then bearing strong children (Emperor Augustus’ famous law encouraged at least three). Martial valor and willingness to die pro patria. Commoners treating patricians with the respect due a noble class, and patricians treating commoners with noblesse oblige.

This paper discusses some of the ancient Roman customs Livy might have been comparing favorably to the dissolute mores of his own era. They include a law that a husband could kill his wife if he caught her drinking - after all, drunkenness could lead to adultery. When Livy talked about moral decline, part of what he meant that the Romans of his day no longer had the stomach to do this. Was he wrong? Are we still equally likely to do that kind of thing today?

The correct interpretation of the Livy quote isn’t “people think morals are declining today, but Livy thought morals were declining in Rome, so clearly everyone’s equally wrong and morals are the same everywhere forever.” If Livy were to see modern America, he would consider us morally insane. No number of polls showing that respect for Hispanics stayed stable between 2002 and 2013 would change his mind. Our only recourse would be to retort back that no, he was morally insane.

I can’t tell you whether morality is increasing or decreasing. But a first stab would be to note that wealth is increasing. We might expect those virtues which wealth makes less necessary, like industry and chastity, to decline - and those virtues which wealth makes more convenient, like compassion and pacifism, to increase. Depending on how much of which virtues you put in your morality portfolio, the overall value could be going up or down.

Since I’ve been pretty harsh on this paper, let me say that I’m more sympathetic to MG’s project when they replace “moral” with specific terms like “honest” and “kind”. Some of their findings suggest that by some definitions of honesty and kindness, these constructs have stayed the same for a while. But they so often switch between definitions that I don’t think they ever manage to simultaneously demonstrate that 1) people think honesty and kindness are declining and 2) they aren’t really. I think they probably could demonstrate these things, and that this would make a good paper that would resemble some of the current paper and which I would approve of. I would still be agnostic as to whether this reflected a bias vs. changing definitions of “honest” and “kind”.

But the actual current paper is more ambitious, and it fails to live up to those high ambitions.

-

Here I’m talking mostly about objective indicators; there are some subjective questions from earlier eras. Also, I skimmed over a lot of these and only looked at the US data; sorry if I missed some from other countries.

-

There’s less homicide today than in 1900, and less violent crime today than in 1990; MG could have chosen to highlight either of these trends. I’m critiquing the one they did highlight to show that their methods are bad, not that crime has really increased or that there’s no argument that it’s decreased/stayed the same.

-

…

-

This isn’t necessarily true. It’s possible for a later year to live up to the moral standards of 1940 better than 1940 does. For example, in 1940 people might believe adultery is bad, but do it anyway, and then in 1980 everyone finds God and stops having affairs and even 1940 has to admit that 1980 is doing things better. Rather, say that there are two forces - moral progress/regress by 1940 standards, vs. moral drift since 1940 (which naturally causes everyone to be worse at 1940 standards, since they’re no longer even trying to achieve them). If the second factor outweighs the first, everyone feels like morality declines since their childhood.