Kids Can Recover From Missing Even Quite A Lot Of School

I. Introduction

Back when the public schools were closed or online, someone I know burned themselves out working overtime to get the money to send their kid to a private school. They figured that all the other parents would do it, their kid would fall hopelessly behind, and then they’d be doomed to whatever sort of horrible fate awaits people who don’t get into the right colleges.

I hear this is happening again now, with more school closures, more frantic parents, and more people asking awful questions like “should I accept the risk of sending my immunocompromised kid to school, or should I accept him falling behind and never amounting to anything?”

(see also this story)

You can probably predict what side I’m on here. Like everyone else, I took a year of Spanish in middle school; like everyone else who did that, the sum total of what I remember is “no hablo Espanol” - and even there I’m pretty sure I forgot a curly thing over at least one of the letters. Like everyone else, I learned advanced math in high school; like everyone else, I can do up to basic algebra, the specific math I need for my job, and nothing else (my entire memory of Algebra II is that there is a thing called “Gaussian Elimination”, and even there, I’m not sure this wasn’t just the name of a video game). Like everyone else, I once knew the names and dates of many important Civil War battles; like everyone else - okay, fine, I remember all of these, but only because the Civil War is objectively fascinating.

And I think that’s the whole point. We learn lots of things in school. Then we forget everything except the things that our interests, jobs, and society give us constant exposure/practice to. If I lived in Spain, I would remember Spanish; if I worked in math, I would remember what Gaussian Elimination was. I think a lot of the stuff you’re exposed to and interested in, a sufficiently curious child would learn anyway; the stuff you’re not goes in one ear and out the other, hopefully spending just enough time in between to let you pass the standardized test.

Even beyond this, school is repetitive. I learned the same Civil War facts in fifth, eighth, and eleventh grade. I think I read The Giver in multiple English classes. And this is just the stuff it’s embarrassing to have repeated. The actually important skills - how to write essays, how to cite sources - get deliberately repeated year after year.

(I still have no idea how to cite a source properly, except a vague memory that something called “MLA Format” was very important, and that there might have been another thing called “Chicago Style” unless I am confusing it with pizza. When I actually need to cite something, I hit the “Cite” button on the top right of PubMed and do whatever it says.)

So my prediction is that an average student could miss a year or two of school without major long-term effects. Their standardized test score would be lower at the end of the two years they missed than some other student who had been in school the whole time. But after a short period they would equalize again. I don’t think you need to burn yourself out working overtime to send your kid to a private school, I don’t think you need to risk your immunocompromised kid’s health to send her to the classroom, I think you can just chill.

I want to present some of the evidence that makes me think this.

II. Evidence In Favor From Various Unusual Situations

In the Benezet experiment, a school district taught no math at all before 6th grade (around age 10-11). Then in sixth grade, they started teaching math, and by the end of the year the students were just as good at math as traditionally-educated children with five years of preceding math education. I interpret this to mean that a lot of education involves cramming things into the heads of very young students who would be able to learn it very quickly anyway when they were older. Certainly it doesn’t seem like a child missing math class in grades 1-5 should have much of a long-term effect.

[update: commenters make a strong argument I am misunderstanding the Benezet experiment; please ignore this paragraph for now]

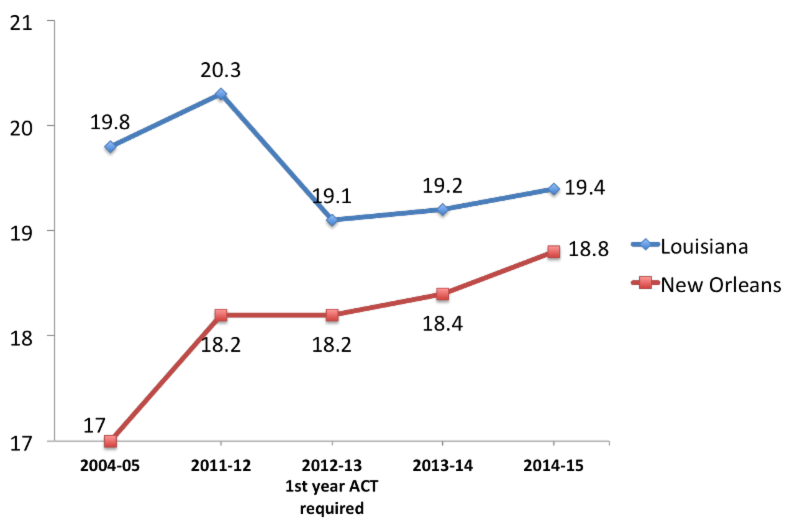

After Hurricane Katrina, lots of New Orleans students had missed a year or two of school (because their school had been destroyed, or they’d had to evacuate the city and live with relatives, etc). After the hurricane, New Orleans switched to a charter-school-based system and test scores went up, with New Orleans students generally outperforming their peers. There’s a lot of discussion about whether this does or doesn’t mean that charter schools are great, but either way doesn’t seem like missing a year or two of school hurt the New Orleanians very much.

Source. New Orleans’ ACT scores improved from pre-Katrina to post-Katrina, even though the post-Katrina kids missed a year or two of school. I don’t want to trivialize the hard work that educators and school reformers probably put in to catch them up - but given that hard work, they caught up. I think educators will also put a lot of work into catching up kids who have to miss school because of COVID.

Source. New Orleans’ ACT scores improved from pre-Katrina to post-Katrina, even though the post-Katrina kids missed a year or two of school. I don’t want to trivialize the hard work that educators and school reformers probably put in to catch them up - but given that hard work, they caught up. I think educators will also put a lot of work into catching up kids who have to miss school because of COVID.

Some parents “unschool” their children. That is, they object to schooling as traditionally understood, so they register themselves as home schooling but don’t formally teach much, limiting themselves to answering kids’ questions as they come up. When adjusted for confounders (ie usually these parents are rich and well-educated), their young children lag one grade level behind public school students on average - but only one (though these students were pretty young and they might have lagged further behind with time). By the time these unschooled kids are applying for college, they seem to know a decent amount, get into college at relatively high rates, and do well in their college courses. I think there’s some evidence that not getting any school at all harms these children’s performance on some traditional measures. But it doesn’t harm them very much. Given how little effect there is from absolutely zero school ever, I think missing a year or two of school isn’t going to matter a lot.

This study tracks the grades of kids with various childhood cancers. It finds that if you have a cancer of the nervous system, a cancer that involves radiation treatment, or a cancer during very early childhood before you start school, you’ll do worse in school over the long term - this seems to be a purely biological result of the cancer or of side effects from the treatment. But other kinds of cancers, especially cancers that develop during school age, don’t seem to decrease grades at all. I assume having cancer as a kid involves missing a lot of school - a kid I knew had cancer and was out of school for months. But this doesn’t seem to affect long-term educational prospects.

Different countries make their kids spend very different amounts of time in school. This has no effect on how much they learn.

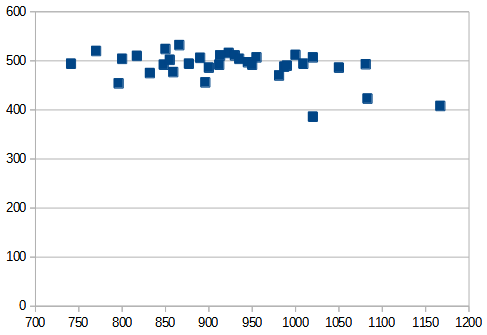

Hours in the secondary school year (horizontal) vs. PISA math scores (vertical). The relationship is significant and negative, potentially because countries that do worse try to extend the school year to catch up. This does not work at all. Even aside from this hastily-thrown-together graph, there’s a large literature on the effect of school length across different schools, US states, and countries. It mostly converges on zero effect - see the introduction here for a run-through.

Hours in the secondary school year (horizontal) vs. PISA math scores (vertical). The relationship is significant and negative, potentially because countries that do worse try to extend the school year to catch up. This does not work at all. Even aside from this hastily-thrown-together graph, there’s a large literature on the effect of school length across different schools, US states, and countries. It mostly converges on zero effect - see the introduction here for a run-through.

I think the evidence suggests that homework has minimal to no effect on learning. If time in school has the same effect as homework, that suggests it’s also pretty low. This also serves as a proof of concept that educators have no idea whether anything they do educates children or not, and there’s no particular reason to draw a connection between “you are turning your children’s time over to these people” and “your children are learning more”.

Before the 1960s, Germany had a very non-standardized school year where different areas would start in all different months. In the 1960s, the government decided to standardize to have the school year everywhere start in autumn. During the transition, some German students got only half a year in a given grade; others got one and a half years. Pischke studies the results, and although he’s able to find immediate effects, there are no long-term effects on things like earnings.

And Potochnik (2018) looks at immigrants who missed school (at least one grade level) during the immigration process. After adjusting for confounders, immigrants who miss a grade during primary school (ie below age ~11) do just as well on tenth-grade (ie age ~15) tests as immigrants who didn’t miss a grade. Immigrants who miss a grade during secondary school (ie after age ~11) do the same on reading, but worse on math, as other immigrants on tenth-grade tests. I interpret this to mean that effects from early school missing wash out after a few years, but that if you miss a grade close enough to when you’re being tested, it hasn’t had enough time to wash out yet (especially with math). One caveat is that school-missing immigrants, even the ones who did academically just as well as everyone else, were more likely to drop out. This could potentially be either non-academic effects, or (more likely IMO) undetected confounders.

III. Supposed Counterevidence From Absences, And Why I Am Pretty Sure It’s Wrong

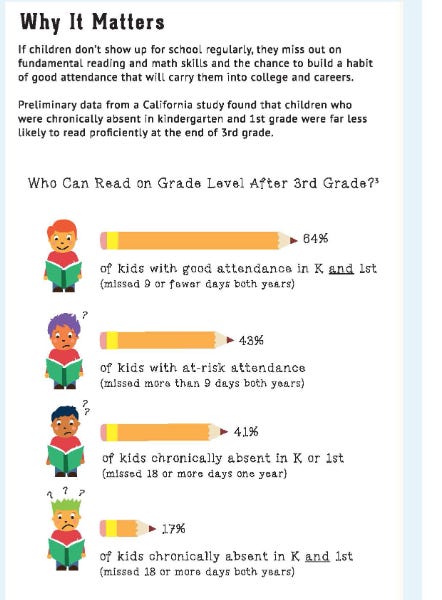

What about everyone saying that “research shows” that being absent from school is terrible for children? There is “research” that “shows” this, but it is mostly terrible. This is a typical example. It finds that increased absences are heavily correlated with worse grades and test scores.

This would not pass a freshman experimental methods course. Obviously this is correlational rather than causal. Kids who are very poor, delinquent, have parents who don’t care enough to force them to go to school, etc - miss a lot more school than rich kids with helicopter parents. These kids are also at more risk of having reading problems. The alternative is to believe that (as these people apparently do) missing two weeks of school makes you 33% less likely to be able to read two years later. Come on!

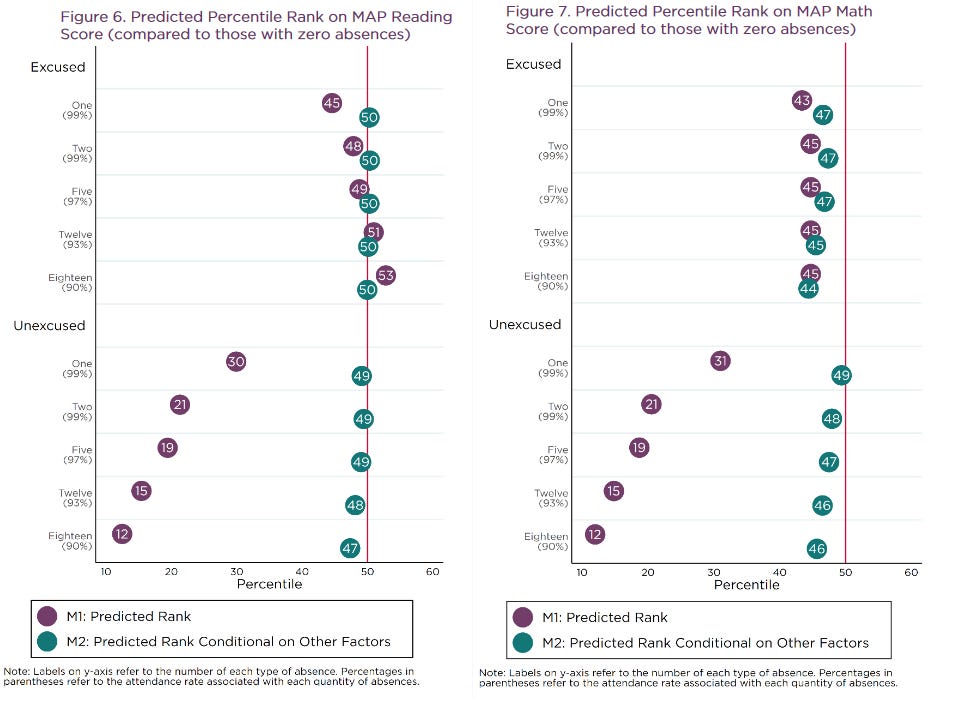

The only study of this sort that I will grudgingly tolerate is this one, which adjusts for some confounders like poverty (remember, you can never adjust for all confounders!) and also breaks absences down by “excused” vs. “unexcused”. Excused absences are things like “the kid is sick and has a doctor’s note”, and probably don’t differ as much based on class and parental investment. Here’s what they find:

Look at Figure 6, bottom half. If you don’t adjust for confounders, someone with lots of unexcused absences goes from the 50th percentile to the 12th percentile. Once you do adjust, they go from the 50th percentile to the . . . 47th percentile, and even that three-point difference is plausibly just unaccounted-for confounders. As for excused absences, they have pretty much no effect whether you adjust for confounders or not. The kids missing 18+ days, ie more than a tenth of the entire school year, do the same or better as kids with zero absences.

Figure 7 is a little more pessimistic. It finds some evidence that children who miss lots of school do worse on math tests, although even here missing 10% of the school year only brings you down from the 50th to 46th percentile. I think this is plausible. If you miss the week that your teacher was teaching eg Gaussian Elimination, you just might not learn how to eliminate Gausses that year (all of these are based on tests at the end of the year where the students were absent). I would still be shocked if, five years later, there is a difference between these two groups. If it’s something important like basic multiplication, the absent kids will pick it up some other time; if it’s something obscure like Gaussian Elimination, the non-absent kids will forget all about it. Remember, in the Benezet experiment students missed five whole years of math instruction, and a single normal year was enough to get them back on track.

IV. Supposed Counterevidence From Disasters and Strikes, And Why I Think It Is Most Likely Wrong

The strongest counterevidence to my position comes from a body of literature on the effect of other long-term school closures, mostly from disasters but occasionally from teacher strikes.

I’m inherently skeptical of these, because I’m suspicious that education researchers love finding that education has huge effects, that any disruption to education is a disaster, and that kids should be in school much more. This is in addition to the usual bias for positive results. Still, the studies exist and we should look at them.

One strain of this literature focuses on snow days. In years where there are more snow days, do children learn less? Often studies find this is true, for example here. But an important caveat - this study finds only that snow days late in the winter (eg February) affect test scores. Early snow (eg November) has no effect. Probably this is because the test they’re using to measure effects is administered in March.

To me this fits with a sort of “teaching to the test” model. There’s no effect on some deep abstract long-term construct of “education” or “knowledge”. But if you’re having Test Review Day a week before the test, and then you can’t do that, that has a big effect. Clearly this won’t affect next year’s test - it doesn’t even affect a test three months out! Claiming that snow days are bad for education is just Goodharting on “scores on the test immediately after the snow day”.

(my own experience with these standardized tests is that eg my school’s social studies courses would move leisurely through the Native American and colonial era, get distracted talking about How Bad Slavery Was, and then a week before the standardized test go into “ohmigod we’re supposed to be at the 1950s now fuck fuck fuck Grant Hayes Garfield Arthur Cleveland Harrison Cleveland McKinley World War One World War Two labor unions Japanese internment ok good luck!” mode. If the day you miss is during that period, I can definitely believe you do worse on test questions about the McKinley administration one week later.)

Also of note, a study by Joshua Goodman finds that snow day closures do not have any noticeable effect on test scores in Massachussetts. Nobody has officially made this connection, but I suspect this is because Massachusetts’ standardized test is in May, when there won’t have been snow days close enough to make a difference.

Another strain of literature focuses on big Third World disasters, like an earthquake in Pakistan. These disasters usually destroy schools and give students a few years’ gap in learning, and studies do find that the students do worse just after the disaster. But importantly, they are doing more worse than the schooling gap can account for - eg if they miss school for a year, they’re two or three years below grade level. Most studies I read attribute this to some combination of malnutrition and PTSD. The grade losses worsen even after the students are back in school (ie they might start two years behind, and after two more years of schooling they’re four years behind). The commentators attribute this to “being promoted too quickly”, but I interpret this as further evidence that something beyond just missing school is affecting this. Given that the Hurricane Katrina study didn’t find this, I suspect that in a First World environment where malnutrition is less of a risk, there’s less need to worry about this.

Then there are teacher strike studies. These generally find that teachers going on strike have large negative effects. I don’t entirely understand their methodology, so I can’t critique them very well, but I have to admit I’m skeptical of them anyway. This one is the classic, but its pattern of effects seems kind of suspicious - a teacher strike in fifth grade is bad for boys’ (but not girls’) sixth grade math scores, but a teacher strike in sixth grade is bad for girls’ (but not boys’) sixth grade reading scores? A strike is four times worse in fifth grade than in sixth grade for reading, but about the same for writing? Possibly I’m misunderstanding this methodology, but otherwise I’m not sure what to think.

On the other hand, this one from Argentina has very robust effect sizes. Being exposed to ten days more Argentine teacher strike doesn’t just decrease test scores, doesn’t just hurt employment and earnings decades later, but even (if I’m understanding it correctly) causes intergenerational effects that decrease the school performance of the children of the students who underwent the teachers’ strike.

I can’t find any specific problems with this study. It just seems extreme to me. We know from the absence data above that missing eighteen days of school doesn’t even decrease your score on that year’s reading test - but missing ten days means you’ll get a worse job as an adult and even rubs off on your children and your children’s children unto the n-th generation? Benezet just didn’t teach math at all for five years and everyone did fine, but if you miss even ten days of your math class you’ll never recover?

(also, compare the second-generation effects of experiencing a 10 day long teacher strike vs. experiencing the Holocaust - the results might surprise you!)

If I had to try to reconcile this study with the others, I might refer to the work on non-academic effects of school - a lot of school-related interventions (like pre-school) don’t improve test scores or any meaningful measure of knowledge, but do seem to help through something like behavioral stability and conscientiousness. This might explain why it’s hard to find effects on test scores, but possible to find effects on earnings years later.

V. Trying To Steelman The Case Against Missing School

Since I’m writing this from a position of bias, I’m going to try to pretend I have the opposite bias, and see what that comes up with.

There are many studies that show that various seemingly-good educational interventions don’t necessarily increase test scores, but do improve graduation rates, decrease youth crime, and achieve other “moral character” type goals. For example, preschool programs like Head Start don’t raise test scores, but do seem to probably prevent dropouts.

Maybe missing school is also like this? There seems to be some hint of this in the study on immigrant children, who were usually able to recover test scores over time, but still dropped out more even after their test scores were fine. This could also explain why the Argentine children in teacher strikes had decreased earnings years later; a lot of the studies linking educational effects to earnings find that connections aren’t mediated by test scores.

Is there any reason to think that missing school might have effects on test scores more than a few years out? Most studies done on primary school students missing school find they eventually catch up; some studies done on secondary school students find they don’t. I previously assumed this was because the secondary school students don’t have enough time to catch up before they stop taking standardized tests and getting counted in these studies (usually 10th - 12th grade), but the evidence doesn’t rule out a scenario where secondary school is actually very important and if you miss it you’ll never catch up. Even if this is not true in a fundamental sense, it could be true in a sense where if you miss (eg) 11th grade, you don’t have enough time to catch up before you apply for college, you get into a worse college than you otherwise would have, and that stays on your resume for life.

I think some of these points are stronger for poor/minority/at-risk kids, and weaker for comfortable/Eurasian/not-at-risk kids. Concerns about dropping out or getting involved in criminal activity only make sense if your kid was on the border of doing these sorts of things, and I suspect the reason school prevents them is that if you come from a really bad household school is the only place you can learn expected values and behaviors - if your household is not that bad, I wouldn’t expect you to have these effects. And evidence suggests (see section 5 here) that getting a good college on your resume is long-term important for disadvantaged children (maybe because otherwise employers would overlook them), but doesn’t have a permanent effect on more advantaged kids.

VI. Conclusions And Open Questions

I don’t want to do the thing where I say some edgy stuff but never commit to anything, so here’s what I think, given with confidence levels even though I’m not sure how you would ever check them. I’m not claiming that these conclusions are the clear conclusion of all the studies above that would be shared by any honest person who understood them - just that they’re my guesses, informed by those studies.

1. A kid who misses a year of primary school will, by high school graduation age, on average be less than 5 percentile rank points behind where they would otherwise have been (85%)

2. …less than 1 percentile rank point (35%)

3. A kid who misses all of 9th grade will, by high school graduation, be less than 5 percentile points behind in reading (60%)

4. …and math (30%)

5. The lowest performing kids might do slightly worse than this on average, and the highest-performing kids slightly better (???%)

If these claims are right, then ten years from now, we won’t find a huge effect of COVID lockdowns on student learning.

This will be hard to measure, because standardized tests generally measure students’ percentile rank relative to their peers, and since everyone was affected by COVID we won’t expect standardized test scores to change even if COVID had severe effects on learning.

I’m sure lots of people will do studies aiming to show that school districts / private school chains / nations that maintained more in-person learning have relatively better test scores than ones that closed for longer periods. I intend to be skeptical of these, because they’re going to end up as really complicated adjust-for-lots-of-confounder multilevel regressions that all find that Model #478 shows that closing schools was worse than the Holocaust so surely that one must be true. I would be much happier if there was some specific large difference we could look at - for example, between some nation that kept its schools completely open vs. some other that locked down all year - but I don’t think the differences are that extreme.

Might we be able to test the effect of COVID school closures on income? If there’s a discontinuity where people who graduated in 2019 make noticeably more money ten years from now than people who graduated in 2021, that might be helpful. But there are a lot of possible confounders there.

What I would really like is some consistent absolute test (ie your score is how many questions you get right, not how well you do relative to others) that all schoolchildren take yearly. I don’t know what this would be. If there was one, I would expect a medium-sized drop for students who take it this year, gradually decreasing to zero after two or three years.

Until then, I think parents should be more relaxed about the risk of their child missing school, especially if it’s relatively early in their school career. They should do whatever makes them, their child, and their family happiest and safest, without losing too much sleep over the educational consequences.