Long COVID: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

Like everyone else, I’m trying to figure out how cautious I should be around COVID. It seems like the most important concern for young vaccinated people like myself is the risk of Long COVID symptoms, so I spent a while trying to figure out what those were.

My basic conclusion is that everyone else is right, that news stories on this phenomenon seem remarkably good, and that there’s not much we know for sure beyond the simple summary you’ve probably already heard. Insofar as anything surprised me, it was how bad the worst-case scenario would be.

Here are some of the basic things I found:

1. Long COVID is probably a lot of different things, some of which are boring and obvious, others of which are still kind of mysterious.

First, people with severe COVID that lands them in the ICU have long-lasting symptoms in multiple organ systems. This isn’t surprising, and should be considered in the context of post-ICU syndrome. Basically, if anything makes you sick enough to land in the ICU, your body is going to be pretty scarred by the illness (and maybe also by the inevitable side effects of intensive care), and this will last a long time and cause many problems. EG if you’re bedridden for many weeks, your muscles waste away, and then it takes a long time for them to recover and you feel weak and fragile until you do. Or if your lungs stop working and you need mechanical ventilation, your lungs might be pretty weak for a while, and other parts of your body might not get quite the amount of oxygen they’re used to and might get damaged in a way that takes a long time to recover. There’s a similar problem where if you are sufficiently old and frail, any illness will take you down a level of functioning and you might not be able to get up a level again. See for example this article discussing how about 1/5 of elderly flu patients have “persistent functional decline” and may never regain their pre-flu level of functioning.

Second, even in young people with milder cases, COVID can sometimes cause lung damage. If you get lung damage, you’ll have at least breathing problems, and maybe other problems. Your lungs will probably heal eventually, but some kinds of lung healing cause permanent scarring; this can present as shortness of breath on exertion, or become a problem later after other lung injuries.

Third, there’s lots of persistent dysosmia and dysgeusia (inability to smell or taste). I think this one is just damage to the nasal passages, plus maybe olfactory neurons accidentally over-adjusting to this damage and forgetting to readjust once you’re better.

Fourth, COVID can probably cause a post-viral syndrome including fatigue. Post-viral syndromes are poorly understood, but might involve something like the immune system being dysregulated and staying in “fight mode” long after the virus is gone. “Chronic fatigue syndrome” is probably something like this, although this is still really controversial.

Fifth, maybe some long COVID is psychosomatic. People hate when doctors bring up the possibility of psychosomatic conditions, and I won’t deny that we tend to overuse the “psychosomatic” diagnosis like it’s going out of style - but some things really are psychosomatic. Chronic Lyme disease (“Long Lyme” rolls off the tongue nicely) is basically universally considered 100% psychosomatic by the medical establishment, although now that I’m thinking about it I wonder if maybe we should be less sure. Lots of people act like psychosomatic = not a real problem. Unfortunately, having a symptom for psychosomatic reasons sucks just as much as having it for any other reason. Sometimes it sucks more, because nobody takes you seriously. I’ll discuss the argument around psychosomatic symptoms more later.

2. The prevalence of Long COVID after a mild non-hospital-level case is probably somewhere around 20%, but some of this is pretty mild.

Giving a percent estimate is kind of meaningless, because it requires a binary yes-no decision on whether or not someone’s symptoms qualify as “long COVID”. Studies that ask “do you think you have long COVID?” tend to get low numbers, presumably because people don’t think their (mild) residual symptoms qualify. Studies that ask “do you have any of the following symptoms?” get higher numbers.

Good studies include a control group who test negative for COVID, to see how many of them have symptoms that would qualify them as “long COVID” if they’d had the disease. Then they subtract the percent of control patients who have symptoms from the number of COVID patients who have symptoms, and assume the difference is caused by Long COVID. While this is better than not doing this, it leaves open the possibility of recall bias, where people who just had COVID are more likely to think a certain symptom is relevant / worth reporting, because they know Long COVID is a thing. There’s also the possibility that people who get COVID are sicker in other ways (eg older, more comorbidities) than people who don’t, which would mean they would have more other symptoms regardless of Long COVID. Some of these studies try to control for this; none can control perfectly.

There’s also high risk of selection bias. Some percent of people with COVID (~30%?) don’t know they had it, and will not volunteer for any of these studies. These people are mostly not severe, meaning that studies that exclude them will overestimate COVID severity. Some, but not all of these studies check seroprevalence to avoid this issue.

That having been said:

Logue et al say that after ~6 months, 33% of outpatients (ie patients who didn’t have to go to the hospital for COVID) had at least one persistent symptom, compared to only 5% of people in the control group (what does it mean for the control group to have persistent symptoms? Presumably they had trouble breathing / fatigue / muscle aches / etc for some reason other than COVID - there’s a certain base rate of all of these problems and apparently in this study it’s 5%).

The British Office of National Statistics looks at people with a confirmed COVID test three months ago, and finds that 14% report having Long COVID symptoms, compared to 2% of a COVID-less control group. This is substantially lower than the earlier study, which found 33% at 6 months. Probably this is because the previous one asked about a bunch of symptoms, whereas this one just asked “Are you having Long COVID?” Lots of people who had some minor symptom or other might not have made the connection, or might have thought that their symptom didn’t qualify for a full diagnosis.

Haverfall et al in Sweden found that 26% of people with previous non-hospital-grade COVID, and 9% of a control group, reported long COVID-esque symptoms after 2 months. After 8 months, this was down to 15% and 3%. I’m not sure why the control group decreased; maybe it was about symptoms that had lasted the whole time, and not point prevalence? Anyway, this was similar methodology to the Logue study, but finds a somewhat lower prevalence. Maybe this is because this study was on healthcare workers, who are generally high-functioning people and who probably did a good job treating their COVID infections? I don’t know, but a lot of these things are really sensitive to how you ask questions and I don’t find the small difference too mysterious.

Sudre et al got data from some kind of UK COVID app with four million users. They chose 4,000 who met various criteria and asked them about long COVID symptoms. 13% reported symptoms after a month, and 2% after three months. This is a lot less than the other studies, so what’s up? I’m not sure, but I think it might be the exclusion criteria, as shown in Supplementary Table 2. When they look at everyone regardless of criteria, they find an estimate centered in the mid 20s, and then the criteria gradually pick away at that. One especially relevant one is that they have no gap in symptom reporting; maybe if you have chronic fatigue, you’re less likely to use an app regularly. But the three month data is still surprising.

Thompson et al get data from a UK longitudinal study. Their headline finding is that between 7.8% and 17% of patients seem to show at least one Long COVID symptom. But they have no control group, so probably it is lower than this. Also, only 1.2% to 4.8% of people say their Long COVID symptoms “impact normal functioning”, which means a lot of people must have some annoying lingering symptoms that don’t really bother them that much.

3. The most common symptoms are breathing problems, issues with taste/smell, and fatigue + other cognitive problems.

From Logue; most of these patients were 6 months post-COVID at followup:

From Haverfall:

Just looking at Haverfall, the fatigue looks kind of fake - little worse in the exposures than the controls. Other studies don’t really show this pattern.

Just looking at Haverfall, the fatigue looks kind of fake - little worse in the exposures than the controls. Other studies don’t really show this pattern.

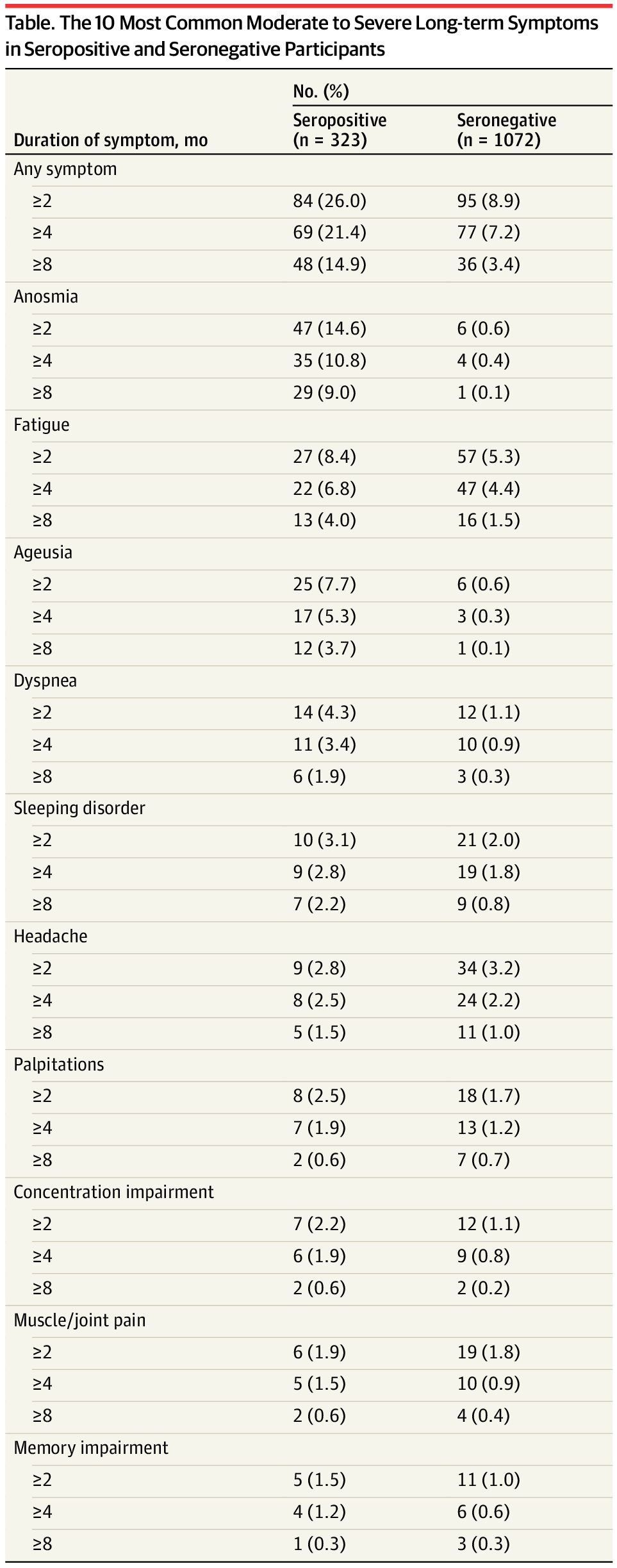

And behold the mother of all COVID symptom persistence studies, Amin-Chowdhury et al:

AC&E act as if this is reassuring - their conclusion starts with “most persistent symptoms reported following mild COVID-19 were equally common in cases

and controls” - but it really isn’t. Not only does this 8-month-out sample find high levels of the expected problems (fatigue/smell/taste/breathing), but it finds some unexpected ones too. Cases are likelier than controls to have cognitive problems and weird neurological issues. One flaw in this analysis is that it didn’t ask for premorbid functioning, so you can tell a story where unhealthy people are more likely to get COVID than healthy ones (maybe they’re stuck in crowded care homes? Maybe they put less effort into staying healthy in general?) But I don’t think this story is true - how come obviously plausibly COVID linked things (like smell problems) are significant, and obviously-not-COVID-linked things like diarrhea aren’t?

One thing this study does reassure me about is mental health. A lot of people claim that long COVID involves various mental health sequelae. This study comes out pretty strongly against it. Sure, lots of COVID patients are depressed - but so are equally many controls. The age of COVID is just a depressing time. In fact, it’s kind of weird that you can get this much fatigue, brain fog, etc without an increase in depression diagnoses.

4. Sometimes problems go away after a few months, other times they don’t

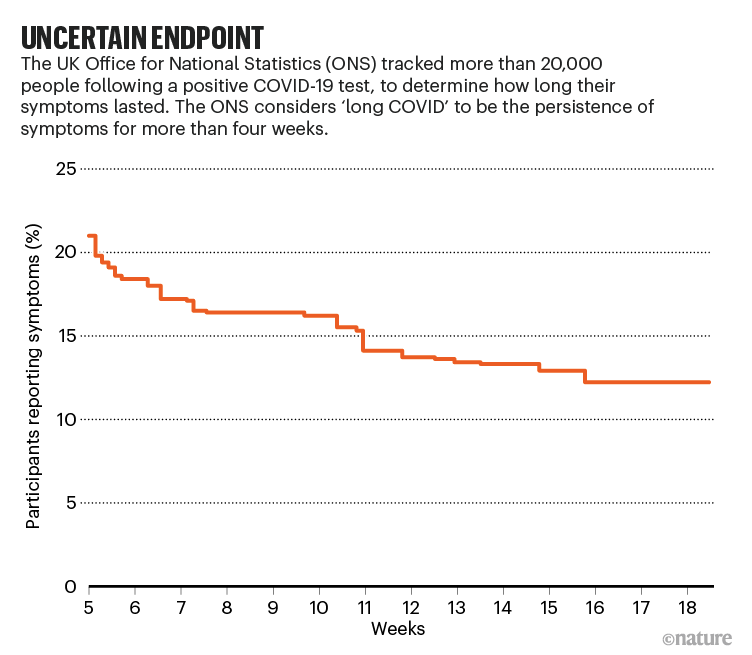

(source)

(source)

This British graph suggests that almost all symptoms are gone after 100 days, which is a lot more optimistic than our studies above.

This is supposedly . . . also the British Office of National Statistics (source). Why are their two graphs so different? My guess is that the top one is a preliminary version without very many patients who had COVID for longer than 12 weeks, and used some sort of model which just assumed numbers there (notice how the confidence intervals widen). The second graph better fits the studies above and is probably the real one.

That’s too bad, because the second graph says that about half of people who have long COVID symptoms after five weeks will still have them after four months. And that graph doesn’t look like it’s planning on falling much further. This kind of matches Haverfall’s study, which found a decrease of a little less than half between two and eight months. There is a very long tail of cases which are not getting better in a reasonable amount of time.

The most likely symptom to last a long time is anosmia, followed by fatigue.

How likely are these to last forever vs. get better in a few years? We’ve only had a year and a half of COVID, but we can make guesses based on other postviral syndromes. Lee et al do this work with 63 patients over three years, and find:

There’s a lot going on here. First of all, how come the severe hyposmia group starts with about the same scores as the mild-to-moderate group? I think because they classified severity objectively, and this is measuring subjective scores? Anyhow, almost everyone improves over this time period, but not everyone reaches normality (defined as a score of 80 or above). This is kind of useless because the study doesn’t tell us how much of this improvement was the first year vs. the second and so on, so we don’t know if improvements petered off or will continue forever. It does mention that people with followup longer than 2 years did better than people with shorter followup than that, but honestly I can’t conclude anything useful from this and there are no better studies.

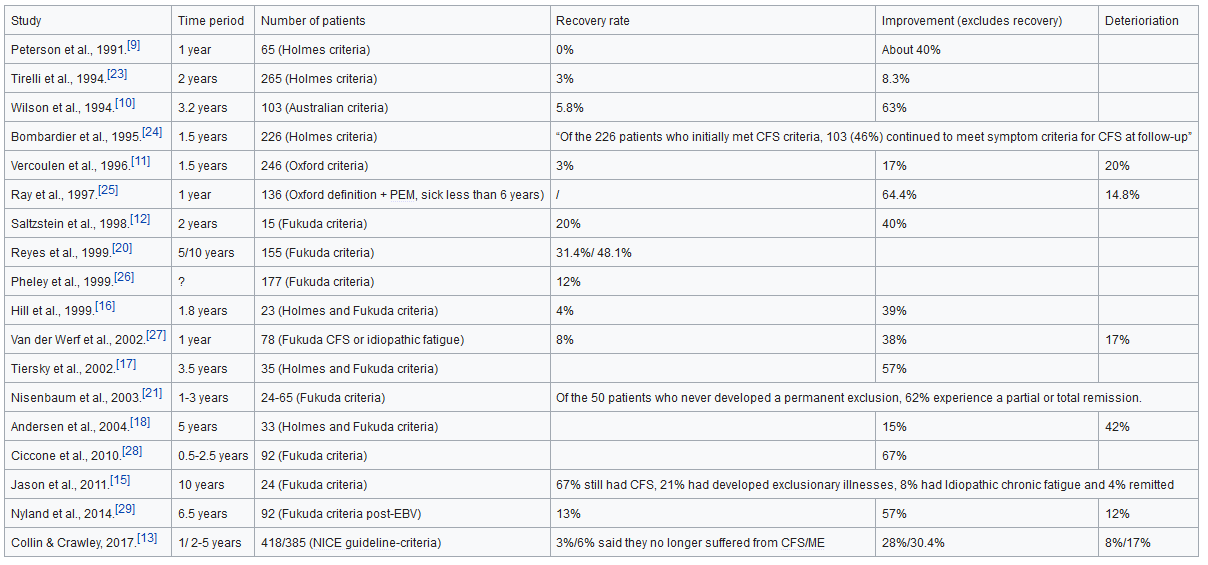

What about fatigue? It turns out that chronic fatigue syndrome patients care a lot about this question and so there are great data. From ME-Pedia:

This is terrible. Recovery rates in the single digit percentages over the space of years. You would think at least some patients would get placebo recoveries, or forget how it felt to be well, or otherwise Lizardman themselves into fake complacency, but no. This is f@#$ing awful.

Maybe COVID won’t be this bad? One ray of hope comes from this Australian study, where doctors record the rates of recovery from postviral fatigue after various rare diseases they encounter (Epstein-Barr, Q fever, Ross River virus). They find that 35% of these patients have postviral fatigue after six weeks, but only 12% after six months, and 9% after twelve months. This sounds a lot better than chronic fatigue.

In fact, these people do the kind of weird task of figuring out how bad different diagnostic labels for fatigue are, even though some might argue that all the labels refer to the same underlying reality. They find an official diagnosis of “CFS/ME” (chronic fatigue / myalgic encephalitis) is much worse than “postviral fatigue”. Using the weird measure of “days per year of followup with diagnosis” (I’m not sure I fully understand their reasoning for why this is good), they find a median length of 80 for CFS/ME vs. 0 for PVF (…huh?). Using the more comprehensible measure of percent who still complain of fatigue after 7-12 months, they find it’s 24% vs. 10% (which super contradicts the above study saying that basically nobody with a CFS/ME diagnosis ever recovers). My guess is that this study had much lower criteria for a CFS/ME diagnosis (some doctor diagnosed it and put it on the insurance records) compared to the ones above (some specialist confirmed it by official criteria). The conclusion I draw is that, while official CFS/ME is horrible and hopeless, there are a lot of things that unofficially look kind of chronic-fatigue-ish which have pretty good prognoses. Since there’s no good reason to think post-COVID fatigue is official CFS/ME as opposed to just some chronic-ish fatigue-ish thing, probably it will have a better prognosis, more like weird Australian viruses.

…which we still don’t know, because AFAICT nobody has done any good studies on postviral fatigue lasting more than a year.

5. Psychosomatic symptoms probably aren’t the majority of long COVID.

I mean, I’m not seeing too many people claiming that they are. There are a lot more people worried that someone else might be claiming that, than people actually making the claim. Still, the Wall Street Journal opinion section is always up for slathering itself in glue and rolling around in a haystack until it becomes the straw man everyone else warned you about, and they do have an article on The Dubious Origins Of Long COVID.

They point out that long COVID was first thrust into the public consciousness in surveys run by Body Politic, who self-describe as “a queer feminist wellness collective merging the personal and the political”. I agree this is a weird source for something to come from, but Hans Asperger was a Nazi and I still use his diagnosis, so I probably have to accept these people’s as well.

More relevantly, WSJ points out that many of the people complaining of Long COVID symptoms test negative for COVID, or at least never tested positive. This complaint conflates the fact that not everyone was able to get a COVID test at all, with the fact that sometimes you get the acute COVID test after you’ve recovered from acute COVID and it’s negative, with the fact that COVID tests don’t have a 100% success rate, with the fact that yeah, okay, some people who didn’t have COVID are probably imagining Long COVID symptoms. I feel like some of the case-control studies above, which clearly show that seropositive people have higher rates of Long COVID than seronegative people, are pretty convincing here.

But also - the people with lung scarring clearly have lung scarring, and most of them have weird x-rays consistent with lung scarring. If you have lung scarring, then you have trouble breathing, you’re fatigued, and you probably have lots of other stuff downstream of that. The people with smell/taste disturbances clearly have smell/taste disturbances, testable with the stupidly named but scientifically venerable Sniffin Sticks test - and also, who even cares enough to make up olfactory problems? Fatigue and brain fog are the only symptoms here that can’t be easily objectively confirmed, and, well, do you think those Australians who got infected with Q fever and had twelve months of postviral fatigue are faking? What about all those post-Epstein Barr fatigue people? Lots of viruses cause postviral fatigue, it’s not really surprising that COVID should also.

(WSJ also spends a while arguing that CFS/ME is just a psychiatric disorder, which I think is not really in keeping with the best recent evidence. Also, as a psychiatrist, I’m very against this conclusion, mostly because if it were true, then people would expect me to cure CFS/ME patients.)

One point WSJ didn’t bring up but could have was that most Long COVID patients are women. Probably this is somewhere between 60 and 80% - I suspect on the lower end of this, because I think women are more likely to talk about these kinds of things than men, and much more likely to eg join Facebook groups. This is noteworthy, because women are traditionally more prone to psychosomatic illnesses - so much that the ancients attributed these to the uterus and called them hysteria (note shared root with eg “hysterectomy”). Women are about 2x as likely to get diagnosed with panic disorder, anxiety disorders, phobias, etc, about 2.5x as likely to get chronic Lyme disease, widely regarded as an entirely psychosomatic condition, and 3-5x more likely to be diagnosed with fibromyalgia. So the female preponderance is suspicious.

But women are also somewhere between 2x and 4x more likely to get autoimmune disorders than men (it varies by disorder - the ratio for Sjogren’s is as high as 16x). There are some pretty crazy hypotheses for why this is - for example, maybe women’s immune systems are permanently upregulated to be prepared for attempts by the placenta to secrete immune-downregulating chemicals during pregnancy, as part of the creepy shadow war between mother and fetus to regulate the maternal environment. I don’t know, do you have a better idea? Anyway, women have more autoimmune issues and more upregulated immune systems, so if there was any good way to assess gender ratio in true postviral fatigue excluding all psychosomatic cases, that would probably be female-biased too.

Probably some Long COVID cases are psychosomatic just like some cases of anything are psychosomatic, but I don’t see too many signs that this is too important in explaining the phenomenon.

…and please allow me a moment of preachiness here.

Chronic fatigue sounds really fake to anyone who doesn’t have it. I think this is because it’s related to willpower. Willpower itself would sound fake to anyone who didn’t have to worry about it. “Oh, so you can go partying with your friends whenever you want, but as soon as it comes time to write a ten page report, your ‘lack of willpower’ prevents you from doing it? A likely story!” Still, all of us (except Bryan Caplan) recognize how real and important willpower is - how having more of it is better than having less of it, and how some condition that caused you to have pathologically little of it would be a huge disaster.

In the comments section to the rough draft of this post, CJ wrote:

I will say - I was one of those types of men to scoff with skepticism at people claiming to have chronic fatigue and the like. I would have called those people lazy and would have been adamant they were faking it or feeling like crap because of unhealthy lifestyle choices. Unfortunately I have learned the hard way the severity of neurological conditions, what it feels like to have brain fog, what chronic fatigue feels like, and how difficult it can be to communicate neurological symptoms to others. I now start from a position of listening to people who are willing to open up about their symptoms and trust that they are being honest. There are millions of people suffering in silence with untreated and undiagnosed disorders - those people are not all faking it or just dealing with psychosomatic conditions. I would recommend Jennifer Brea’s documentary, Unrest. Thank you for shedding some light on the subject.

Heron added:

I second the suggestion to watch ‘Unrest,’ and to consider the many unseen ill whose symptoms are deemed to be imagined. Until this last year, I had little patience with, and doubted, people who I saw as hypochondriacs. Then I became the thing I hated.

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Long COVID do have similarities from what I’ve read, since becoming ill in August 2020. At that time, here in Northern Ireland, there was scant availability of COVID tests; after spending three days trying to get hold of one, (by which time I’d stopped teaching my post-grad online classes & I haven’t worked since) I became too ill to do anything. I figured if this was COVID I’d gotten off lightly, mostly constant severe headache, inability to think, a new experience of fatigue, high temperature, insomnia, hypersomnia, paresthesia, no smell or taste etc Debilitated but not dead. Except for the fact that I still have the aforementioned symptoms a year on and whilst they fluctuate in type and severity, the fatigue, headaches and cognitive difficulties are real. A brain scan, an appointment for brain and spinal MRIs (waiting lists, even when going private [as NHS has 3-8 yr waiting lists here in NI] are lengthy), rare virtual doctors and neurologists suggest my ailments constitute a post-viral thing, maybe Long C, they can offer nothing but pills for pain. There is no test for ME/CFS yet, nor a Long C test, symptoms and presentation are so varied. Given a widespread lack of knowledge and resources regarding these ailments, you’re on your own. Maybe I’ve developed ME, I certainly have post-exertional malaise which my very prominent neurologist hadn’t heard of. Looking at the history of ME/CFS* and a dearth of research surrounding it, I hope that rather than dismiss the lives of sufferers of this or the long-lasting aftermath of COVID, that those experiencing such difficulties will be heard and learnt from. I only understood when I had no alternative.

I don’t think I ever actively pooh-poohed CFS, but like everyone else who encountered it, I underestimated just how bad it was until I met some patients with the condition. It is real and really bad. For whatever reason it is hard to think about and take seriously, but it really is as bad as people say.

</preachiness>

6. Long COVID is probably rare in children

This matters a lot, because children are (currently) ineligible for the vaccine, and also likely to encounter the virus at school. But children usually have mild cases of COVID and don’t die from it, so it’s tempting to just not worry about them. But if they could get Long COVID, that would make it much less tempting.

Preliminary Evidence On Long COVID In Children sounds like a good paper to draw conclusions from. It says 42.6% of children with COVID experience long-term follow-up symptoms, which would be higher than the rate for adults. But it has no control group, and most of the symptoms it finds don’t seem very COVID-related (eg rashes, constipation). The most common symptom (20%) is insomnia, which better studies in adults fail to associate with real Long COVID. The rate of known long COVID symptoms (eg taste and smell problems) is only about 3-4%, and no higher or lower than anything else. Probably these kids are just having problems at the usual rate and attributing them to their recent COVID.

Blankenburg et al do the correct thing and ask a thousand children about potential symptoms, then compare the number who say yes vs. no among COVID-seropositive and seronegative subjects. They find no difference between the two groups. Both are reporting a lot of insomnia, etc. They reasonably attribute this to pandemics being a stressful event that it’s natural to lose sleep over. This is really reassuring, but it can’t rule out a somewhat rarer syndrome. The authors say that they might miss symptoms with a prevalence of less than 10%, and one of them gives his own personal guess that it’s 1%.

An English team says there’s a Long COVID rate of 4.6% in kids. But there was a 1.7% rate of similar symptoms in the control group of kids who didn’t have COVID, so I think it would be fair to subtract that and end up with 2.9%. And even though the study started with 5000 children, so few of them got COVID, and so few of those got long COVID, that the 2.9% turns out to be about five kids. I don’t really want to update too much based on five kids, especially given the risk of recall bias (ie you might notice / care about your symptoms more if you know you had COVID before getting them).

My overall conclusion here is that long COVID is rarer in children than adults, and may not exist at all. The studies tell us it’s probably somewhere less than 5% of kids, but so far we can’t conclude anything stronger than that.

7. Vaccination probably doesn’t change the per-symptomatic-case risk of Long COVID much

Here’s a complicated Twitter thread about this. Of vaccinated people who got symptomatic COVID, about a third ended up with Long COVID symptoms, the same rate as in unvaccinated people.

Of course, vaccinated people are much less likely to get symptomatic COVID. But even conditional on getting it, they’re still much less likely to go to the hospital, die, etc. It would have been nice if the same was true of getting Long COVID. But it doesn’t look that way.

(all this information is from an online poll by a sketchy group of COVID “survivor” activists. But they wrote up their poll in the scientific paper font, as a PDF and everything, so I say we count it anyway)

This NEJM study wasn’t exactly designed to look for Long COVID in vaccinated people. But they found it anyway, at a rate of 19% after 6 weeks. This also fits within the (wide) range reported for unvaccinated people. They don’t give a symptom breakdown beyond “prolonged loss of smell, persistent cough, fatigue, weakness, dyspnea, or myalgia”, which sounds like the usual set.

These studies are pretty weak, and you could argue that given that vaccines decrease the average severity of COVID infection, and infection severity is linked to Long COVID risk, we should have a strong prior on vaccines decreasing Long COVID risk. And just before publishing this, someone sent me this study, which very preliminarily finds vaccines might decrease Long COVID risk by a factor of 2. I think a factor of 2-3 is believable; one of 10 or 20, less so.

Weirdly, there are some claims that vaccines can help relieve symptoms of existing long COVID. Sounds kind of like sympathetic magic to me, but the researcher quoted in the linked article said it might “improve symptoms by eliminating any virus or viral remnants left in the body” or by “rebalancing the immune system”. So yeah, sympathetic magic.

8. Your risk of a terrible long COVID outcome conditional on COVID is probably between a few tenths of a percent and a few percent.

My original calculation went like this:

About 25% of people who get COVID report long COVID symptoms. About half of those go away after a few months, so 12.5% get persistent symptoms. Suppose that half of those cases (totally made-up number) are very mild and not worth worrying about. Then 6.25% of people who get COVID would have serious long-lasting Long COVID symptoms.

After doing that calculation, I read this essay by Matt Bell, who tries to figure out the same thing. He is much more optimistic. He agrees that about half of long COVID cases go away after a few months, but adds another 50% decrease from “few months” to “lifelong”, kind of on priors, admitting there’s not too much positive evidence for this. Then he adds another factor-of-two decrease from vaccination, based on very preliminary studies from the UK. He estimates that someone with my demographics (vaccinated man in his 30s) has a 2% risk of Long COVID conditional on getting COVID at all. Then he divides by five for the true worst case scenario, based on studies showing that a fifth of people with Long COVID report that it affects their daily activities “a lot”. So by his final number, I have an 0.4% chance of getting really terrible long COVID, conditional on getting COVID at all.

My friend AcesoUnderGlass also did a writeup of this, published after I did my first-draft calculation, which seems to be thinking of this very differently, based entirely on hospitalization rates (which of course are very low in vaccinated people our age). She accordingly concludes that risk is very low. I don’t really understand her reasoning here, but I trust her a lot and am working on trying to converge with her on this.

What’s my yearly risk of getting COVID if I try to live a normal life?

This site says only 0.1% of vaccinated Californians have gotten COVID after their vaccination. But vaccination was pretty new when that survey was done, so we might want to take this as a per one-to-two-months estimate. That would mean a risk of 0.5 - 1 percent per year. But not all these people are living normal lives, so my risk might be higher.

MicroCOVID gives me a good sense of how careful I’d have to be to stay within a risk budget of 1% COVID risk per year. When I play around with it, I think I am about 5x - 10x less careful than that, which would mean a risk of about 5%/year.

This tracker suggests my area has recently had about 1 new case per thousand people per week, which would imply 5% per year. But most of those people are probably unvaccinated, so my risk would be significantly lower than that.

I’m going to round all of this off to about 1% - 10% per year of getting a breakthrough COVID case (though obviously this could change if the national picture got better or worse). Combined with the 0.4% to 6.25% risk of getting terrible long COVID conditional on getting COVID, that’s between a 1/150 - 1/25,000 chance of terrible long COVID per year.

How does this compare to other risks? My ordinary risk of death per year, just from being a man in his 30s, is about 1/700 (though this includes drug abusers and stunt pilots, so my real risk might be lower, let’s say 1/1000). Here are some other risks, courtesy of the BMJ:

In this context, I find the 1/150 risk pretty scary and the 1/25,000 risk not scary at all, so, darn, I guess there’s not yet enough data to have a strong sense of how concerned I should be.

9. This is hard to compare to other postviral syndromes

Going into this, I wondered if we might be able to ignore Long COVID. The argument would go like this: all viral diseases have a risk of postviral syndromes. Colds, flus, mono, lots of stuff that’s going around all the time. Lots of people get those postviral syndromes, and either recover or don’t, but either way we don’t make a big deal out of it. Since COVID’s considered “newsworthy” in a way flu isn’t, we obsess over its postviral syndrome even though it’s no worse than anything else’s.

This wouldn’t make Long COVID any less bad, and maybe we would be wrong to not panic more about colds and the flu, but it would at least give us some context and make things feel less scary.

Unfortunately, I can’t find anything supporting or opposing this picture. The only relevant study is a meta-analysis by Poole-Wright et al, who (contra nominative determinism) don’t pool the studies by condition, which makes it hard to draw conclusions. I think all of their examples of postviral syndrome after flu are from severe hospitalized cases, so any comparison with COVID would be unfair. Although there do seem to be scattered reports of post-flu problems, they’ve never been formally studied or quantified.

Mononucleosis is an infectious disease caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, affecting about 1/2000 people per year in developed countries. It has a famously nasty postviral syndrome, which this paper describes as “almost one-half of the group had substantial ongoing symptoms 2 months after onset and… ∼10% had disabling symptoms marked by fatigue lasting ≥ 6 months”.

Flu is as common as COVID, but nobody really talks about it having a significant postviral syndrome so probably it’s not that bad. Mono has a worse postviral syndrome than COVID, but it’s rare enough that it doesn’t cause massive society-wide effects. COVID is right in the middle: more common than mono, and (probably) worse postviral syndrome than flu. I think it’s fair to say that we may not have encountered a condition with this exact combination of risk factors and can’t dismiss it as similar to conditions we currently ignore.

One potential analogue might be the Spanish Flu of 1918. It was an equally widespread pandemic, and seemed to have some kind of postviral syndrome. From TIME:

In what is now Tanzania, to the north, post-viral syndrome has been blamed for triggering the worst famine in a century—the so-called “famine of corms”—after debilitating lethargy prevented flu survivors from planting when the rains came at the end of 1918. “Agriculture suffered particular disruption because, not only did the epidemic coincide with the planting season in some parts of the country, but in others it came at the time for harvesting and sheep-shearing.” Kathleen Brant, who lived on a farm in Taranaki, New Zealand, told Rice, the historian, about the “legion” problems farmers in her district encountered following the pandemic, even though all patients survived: “The effects of loss of production were felt for a long time.”

The 1918 flu seemed to have lots of psychiatric effects: “Norwegian demographer Svenn-Erik Mamelund provided such evidence when he combed the records of psychiatric institutions in his country to show that the average number of admissions showed a seven-fold increase in each of the six years following the pandemic, compared to earlier, non-pandemic years.” Coronavirus doesn’t - the excellent Amin-Chowdhury study above finds nothing. Still, this is the scale of thing I’m worried about.

The worst case scenario here is really really bad. If a few percent of COVID patients get long-term unremitting genuine CFS/ME, that has the potential to overwhelm government welfare budgets and long-term depress the economy. I think there’s a 90% chance the real situation isn’t that bad, but it’s scary that we can’t entirely rule it out. Aside from the somewhat different 1918 case, I don’t think we have any historical experience of dealing with postviral syndromes at this scale.

The medium case scenario is something more like “a few percent of infected people get moderate fatigue, which doesn’t really prevent them from working, and goes away after a few years”. I don’t know whether the level of media attention paid to this would converge on “boring and nobody notices” or “giant disaster”, and I think it would be compatible with either.

10. Conclusions

1. Long COVID is many different issues without a common mechanism.

2. Some of these are straightforward and not surprising, eg lung scarring and post-ICU syndrome from severe infection, and would happen in any disease of this severity. Others seem to be more like the poorly-understood postviral syndromes associated with several other diseases. While some symptoms may be psychosomatic, most are probably organic.

3 The three major categories of symptoms are straightforward cardiovascular-pulmonary issues, straightforward smell and taste issues, and more mysterious neurological issues.

4 Although these get better with time in some people, in a significant number (maybe ~50% of people who had them at six weeks) they persist for as long as anyone has been able to measure them (a few months in the case of COVID, a year or two in the case of comparable syndromes).

5. Post-COVID fatigue is particularly concerning. This would be very bad if we analogized it to CFS/ME, and still pretty bad if we analogized it to other known postviral syndromes. There is no proof that this always gets better over the long term, although no study has looked at them for more than a few years. Facing postviral fatigue on this scale is a new problem.

6 . Children probably get Long COVID less than adults, probably at a rate of less than 5% of symptomatic cases. But we don’t know how much less, and we can’t rule out that some children get pretty severe symptoms.

7. Although vaccination decreases the risk of symptomatic COVID, it probably doesn’t decrease the risk of Long COVID per symptomatic COVID case by very much, though it might decrease it by a factor of 2-3.

8. Your chance of really bad debilitating lifelong Long COVID, conditional on getting COVID, is probably somewhere between a few tenths of a percent, and a few percent. Your chance per year of getting it by living a normal lifestyle depends on what you consider a normal lifestyle and on the future course of the pandemic. For me, under reasonable assumptions, it’s probably well below one percent.

EDIT: Here are some other people who tried to do this same analysis. I learned about all of these after I wrote the first draft of this, so you can consider the basic thought process here to be independent of them - but I edited some things to account for what I learned from them before writing the final version.