Mantic Monday 11/1/21

Keynesian Beauty Contests

I have no source for this, someone told me about it at a meetup.

Suppose you want to run a forecasting tournament on whether nuclear war will destroy civilization by 2100. But nobody cares how much money they have in eighty years, plus if civilization is destroyed you can’t collect your winnings.

There are lots of kludgey solutions to this, but one possibility is a Keynesian beauty contest. Get a lot of isolated teams, and make them predict what all the other teams will guess. Whoever gets closest to the average wins the prize.

Let’s start with the good: in theory, this does solve the problem. Presumably the easiest way for the teams to all guess the same is to converge on the “right” answer. In some sense, the definition of probability is what a smart person who knows a certain amount of information should estimate, so if you ask someone to predict what a person just as smart as you who has the same information as you will estimate, that’s like asking for your probability.

Okay, that’s in theory. In practice there are a lot of ways this could go wrong. For example, one stable equilibrium is that the right answer is the obvious Schelling point so everyone tries to coordinate around that. But another stable equilibrium is that “one thousand” is a very round number, so everyone tries to coordinate around that. Probably you can prevent that by hiring one expert to make an educated guess outside of the beauty contest, and including that in the mix.

A more serious problem is that it penalizes anybody who’s smarter and better-informed than average. If you come up with some really clever argument for why nuclear war is more/less likely than everyone else thinks, but you don’t think other people will come up with the same argument, Keynesian beauty contests incentivize you to ignore it (whereas prediction markets incentivize you to buy as many shares as you can to exploit your superior information). If you happen to overhear Vladimir Putin saying he’s going to start a nuclear war tomorrow, then in a Keynesian beauty contest you should just sit on this information (in a prediction market, you should insider trade and make a killing).

Finally, the need to isolate everyone limits your options. You can’t do this in a prediction market; you would have to have a tournament. And you can’t do an open tournament, because then lots of stupid people would be in it and the challenge would be figuring out what stupid people would guess. My source says that the Good Judgment Project is looking into this, which makes sense - they’re the kind of closed tournament between savvy forecasters where this could actually work.

This Week In PredictIt:

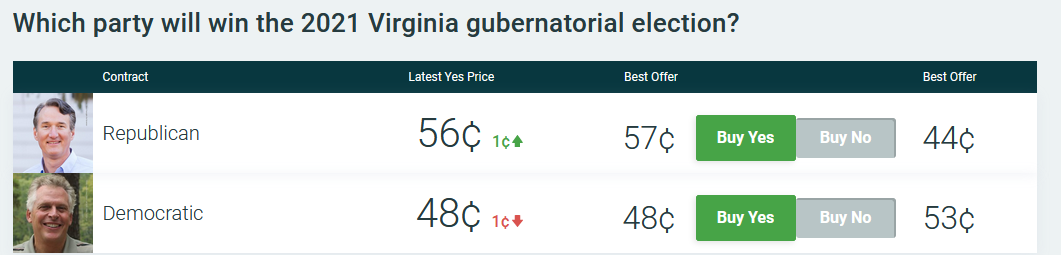

The big news in the US is the upcoming Virginia election:

(source)

(source)

Wait, what? That wasn’t how things looked the last time I…

(source)

(source)

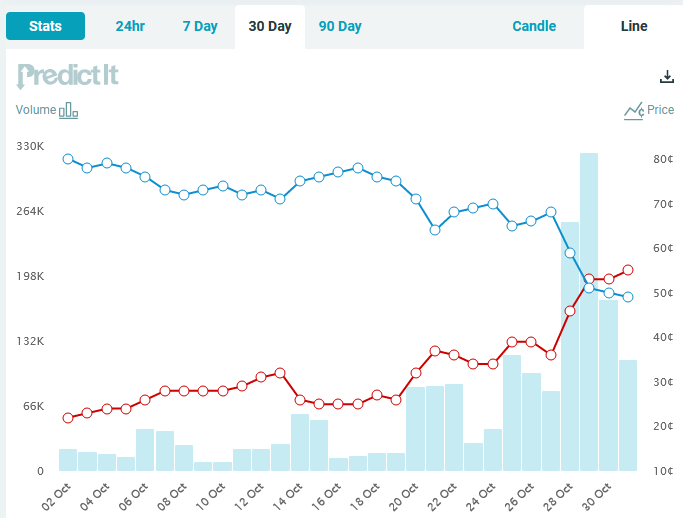

Looks like a big shift in the Virginia gubernatorial election market, mirroring a shift in the polls:

(source)

(source)

A lot of this comes from a single Fox poll which found found Youngkin way ahead. There’s been some debate over how much to trust it, but it looks like both 538 and the prediction markets trust it quite a bit.

Why the big shift? Washington Post blames McAuliffe’s comments that parents shouldn’t get to tell schools what to teach, putting him on the wrong side of debates over critical race theory, etc. And probably the thing where some of his supporters were caught pretending to be pro-Youngkin white nationalists didn’t help.

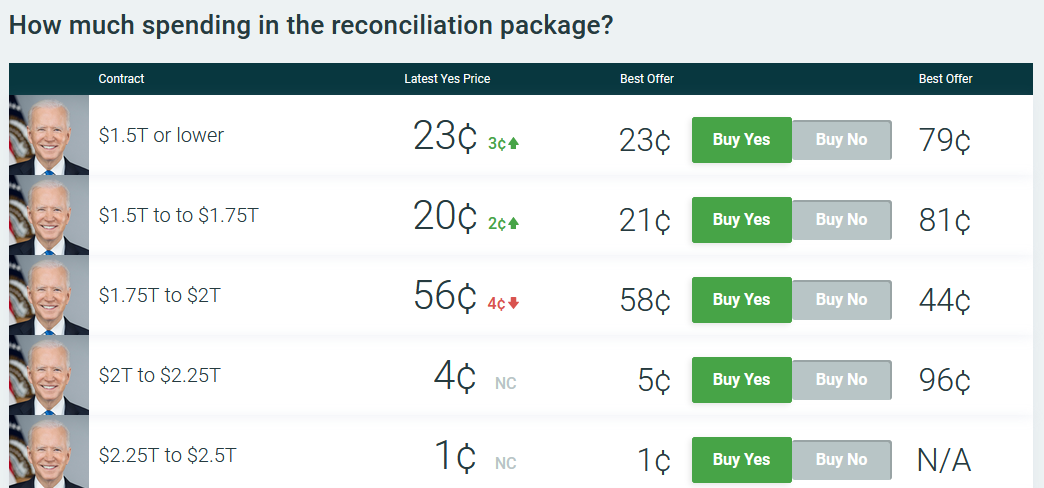

Moving on to the national level:

(source)

(source)

The markets have been working on how much money will be in the Democrats’ omnibus social programs bill when progressives and Manchin/Sinema finally come to an agreement.

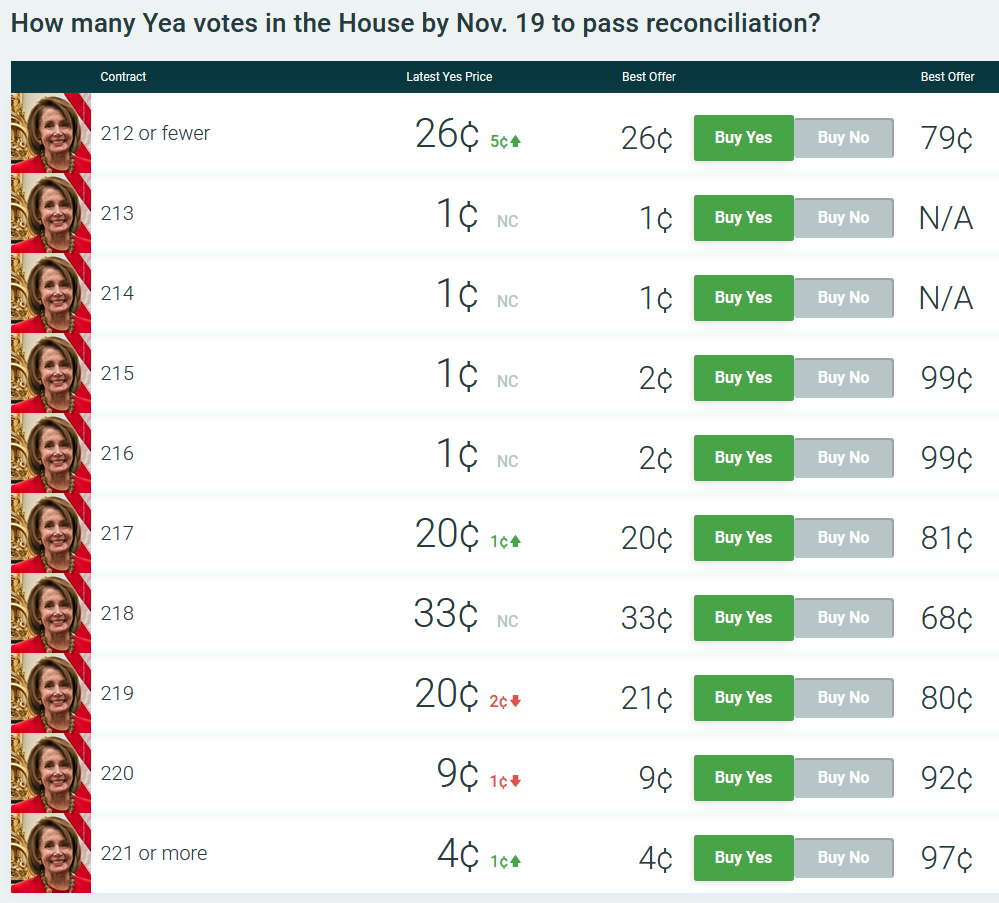

(source)

(source)

…and on when it will pass. Looks like people are optimistic.

Teacher Merit Pay

I want to provide some exegesis on this Tweet:

Eliezer Yudkowsky @ESYudkowskyDath ilani: conditional prediction markets over students’ performance observables one year later.

Eliezer Yudkowsky @ESYudkowskyDath ilani: conditional prediction markets over students’ performance observables one year later.  Nicole Barbaro @NicoleBarbaroMany faculty do not agree that student teaching evaluations are a valid assessment of their teaching and do not want them used in hiring, promotion, or tenure decisions by their institutions. Faculty: What ARE the methods by which your teaching should be evaluated?3:56 PM ∙ Oct 23, 2021

Nicole Barbaro @NicoleBarbaroMany faculty do not agree that student teaching evaluations are a valid assessment of their teaching and do not want them used in hiring, promotion, or tenure decisions by their institutions. Faculty: What ARE the methods by which your teaching should be evaluated?3:56 PM ∙ Oct 23, 2021

(not on the dath ilani part, that’s too bottom-of-the-conspiracy-iceberg-meme, but the rest of it)

So suppose you want to do teacher merit pay, or fire the bad teachers and promote the good ones, or something else that involves knowing how good a teacher is.

If you treat “teachers whose students get high test scores = good”, then you’ll just promote teachers who work in rich areas, or who get lots of smart students, or some other confounder related to student selection effects.

What if you promote teachers whose students tend to gain many points on their (relative position in) test scores compared to last year? This is the idea behind value-added models ie VAM, which were big in education about five years ago (see section II - III here for more). Various studies show this works much less well than you would think. Certain classes, races, and genders of students consistently produce higher VAM than others, and a teacher’s VAM can apparently predict their students’ past performance, which makes no sense unless there’s some kind of bias going on. These aren’t useless, but they’re not great, and the problems are severe enough that they’ve become politically toxic.

How would you solve this with prediction markets? Suppose you got a bunch of specific students, published lots of data about them (race, gender, ZIP code, previous test scores, etc), published lots of data on the teachers in the school (education, preferred instruction philosophy, previous students’ test scores, etc), and asked market participants to predict little Johnny’s test scores conditional on ending up in Mrs. Andrews’ class, vs. in Mrs. Brown’s class. They say he would get an 83% on the test if he got Mrs. Andrews vs. an 81% if he got Mrs. Brown. Boom, Ms. Andrews is the better teacher and deserves more money or whatever.

(if you don’t like standardized tests, replace this with some other outcome like graduation rates or acceptance to top colleges)

The idea is that market participants are incentivized to figure out biases in the data and adjust for them in a way that dumb algorithms like VAM aren’t. If VAM attributes higher teaching skill to teachers who get classes full of white kids, then VAM sucks and you’re screwed. If a prediction market attributes higher teaching skill to teachers who get classes full of white kids, then that’s a bias and someone who notices the bias can beat the market by bidding it back down to the right level.

Okay, but how do you get a prediction market on every student and every teacher in a country of millions of people? Well, it would have to be automated. You’d have different teams competing to come up with algorithms based on past performance, and applying them massively at scale to datasets consisting of data about real teachers and real students. Then (some subset of) the students would be randomized to different teachers, and whoever guessed the test scores right would get lots of money.

Once you’ve got this, you’ve also got the ability to answer questions like “how would my child do at public school vs. Montessori school vs. Success Academy”? If the prediction markets say the test scores would be about the same no matter what, then Freddie de Boer is right, private schools are all grifts, and the whole thing is hopelessly confounded by selection bias.

This Week In Metaculus

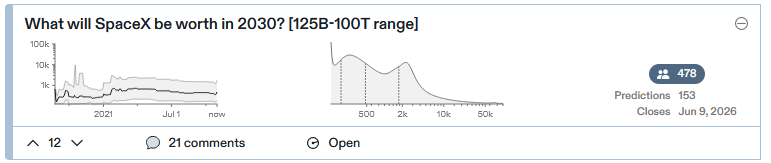

(source, units are billions of dollars)

(source, units are billions of dollars)

AFAIK, right now SpaceX is worth about $100 billion. But the median estimate for 2030 is $500 billion. An 8% rate of return over nine years is ~100%, so even in a great economy the average company will “merely” double by then, whereas SpaceX will quintuple. Seems bold to say a company is undervalued by a factor of >2. I guess this doesn’t technically violate any theorem about stock markets or prediction markets because SpaceX is a private company. Maybe $100 billion is its valuation by normal private investors, and $500 billion is what the sort of people who buy Tesla stock would give it, and Metaculus is siding with the Tesla buyers? Still, take it public!

(source)

(source)

Lots of online learning startups hope to disrupt college. Intellectuals like Bryan Caplan have been pointing out that college gives people a lifetime of debt for little value beyond signaling, and business leaders like Peter Thiel have tried to incentivize young people to break out of the college racket and gain education and experience in other ways.

Caplan wishes the college bubble would deflate, but he bets it won’t. Metaculus makes the same bet, albeit not very strongly. They estimate only a 20 - 25% chance that the rate of college enrollment will go down by 10% (not 10 pp) in the decade 2015 - 2025.

So far we only have data up to 2018, but between 2015 and 2018 numbers have gone up , from 29.9% to 31%. But here is a very different data source that calculates its numbers differently and says enrollment is way down because of COVID. Not sure if that will last until 2025, though.

(source)

(source)

GPT Codex is an AI that auto-completes code for programmers. You can see a really amazing and/or rigged demo here:

Programmers who have worked with it are really impressed, but also say it’s not quite ready for real jobs. Certainly OpenAI would like to make it ready as soon as possible.

Hence the market above: how frequently will the average programmer (who follows Robin Hanson’s Twitter, so maybe an early adopter) use Codex in 2026?

The median guess is 3/4 of an hour. On the one hand, in some sense that’s not much time. On the other hand, it either means every programmer uses it 45 min/week, 10% of programmers use it 450 minutes/week (= 8 hours), or 2% of programmers use it all the time. Any one of those actually sounds a lot more impressive than the original framing!

Maybe Metaculans don’t understand how strong a claim they’re making here? Or they’re expecting response bias on Hanson’s poll? Or who knows, maybe they think a decent fraction of programmers will be using this a decent fraction of the time five years out.

Also, this is an interesting example of using a Twitter poll to power a prediction market resolution, and so far it seems to be going well.

Everything In Moderation

I’d previously missed this 2018 post by Vitalik Buterin proposing prediction markets as a social media moderation plan.

Suppose we want to moderate ACX comments. Maybe you all trust me as moderator, but I am busy and don’t want to read all 1000 comments underneath every post. You could email me to alert me to specific bad comments, but maybe some people overdo it and I’m spammed with lots of dumb moderation request emails. Or maybe the blog gets more popular, there are 10,000 comments , and I don’t even have time to read all the ones I’m alerted to.

Reddit solves this with an upvote-downvote system, but it’s vulnerable to brigading (eg all the conservative posters get together and agree to downvote all the liberal comments). How would you get an upvote-downvote system to mimic my (presumably excellent) moderation judgment?

Merge the system with a prediction market. An upvote invests $1 (Vitalik says 1 ETH, but the post is from 2018 and maybe he didn’t expect that to be worth $4325) in a prediction of “Scott won’t ban this”. A downvote invests $1 in a prediction of “Scott will ban this”. A certain randomly-selected subset of posts with high downvotes come to my attention, I ban/don’t ban them, and everyone collects their winnings/cedes their losses. If the prediction market fits the usual conditions for accurate pricing, it should mimic my judgment as closely as humanly possible - and so I could just have any sufficiently downvoted post get auto-banned. You could have one guy moderating a site the size of Reddit (not a specific subreddit, the whole site) and still have it work pretty well. No more moderator drama!

(or at least much higher variance in the size of moderator drama)

The main flaw I can come up with in five minutes of thinking about this: suppose there’s some obviously terrible post, like outright spam. Nobody would predict I don’t ban it, so how would there be any money to reward the people who correctly predict I will? Maybe there’s a 1% tax on all transactions, which goes to subsidizing every post with a slight presumption toward don’t-ban.

Also, if I were to play this prediction market, I could insider trade and steal all your money. I guess if you trust me enough to make me a moderator, maybe you also trust me enough not to do that?

If somebody actually wants to code this, let me know, and I’ll see if I can get Substack to let me use it (though I’m not holding my breath)

Vitalik didn’t end with “and we should also replace all lower courts with prediction markets about what the Supreme Court would think”, but I’m not sure why not.

Links

— Tyler Cowen article in Bloomberg on prediction markets: “They make economic sense, but for some reason have never really taken off.”

— High-level player Avraham Eisenberg gives some of his Tales From Prediction Markets. EG:

There was a market on how many times Souljaboy would tweet during a given week. The way these markets are set up, they subtract the total number of tweets on the account at the beginning and end, so deletions can remove tweets. Someone went on his twitch stream, tipped a couple hundred dollars, and said he’d tip more if Soulja would delete a bunch of tweets. Soulja went on a deleting spree and the market went crazy. Multiple people made over 10k on this market; at least one person made 30k and at least one person lost 15k.

— Not exactly a prediction market (in fact, kind of the opposite of a prediction market insofar as it delights in things without objective answers), but here are Venkatesh Rao’s Twitter followers trying to predict the 2020s along a bunch of dimensions, eg:

— DARPA investigates how prediction markets do vs. expert surveys when guessing the results of social science studies. Answer: neither of them does well. Some suggestive evidence that averaging the price of the prediction market over a while does better than taking the final price, at least in these very non-liquid markets.

—UC Berkeley AI researcher Andrew Critch gives his predictions for the next few decades.

— In the US, real-money prediction markets are still illegal, unless they’ve undergone the harrowing, expensive, and highly constraining process of registering as a securities exchange. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the relevant regulatory watchdog, is investigating Polymarket for not doing this. I hope everyone involved will be able to come to an agreeable solution instead of crushing what’s currently the leading prediction market or forcing it to become worse.

— Jacob Steinhardt: “Earlier this year, my research group commissioned 6 questions for professional forecasters to predict about AI.” Updates And Lessons From AI Forecasting.

— The superforecasters have a Substack now, although they don’t seem to have posted any more after making a July forecast that Kabul had a 6% chance of falling before September (which it did).

— And CrowdMoney.io is another great prediction market newsletter including interviews with lots of key players in the field.