Mantic Monday 11/15

Reciprocal Scoring, Part II

I talked about this last week as a potential solution to the problem of long-term forecasting. Instead of waiting a century to see what happens, get a bunch of teams, and incentivize each to predict what the others will guess. If they all expect the others to strive for accuracy, then the stable Schelling point is the most accurate answer.

Now there’s a paper, by Karger, Monrad, Mellers, and Tetlock - Reciprocal Scoring: A Method For Forecasting Unanswerable Questions.

They focus not just on long-run outcomes but on conditionals and counterfactuals. The paper starts with an argument against conditional prediction markets that I’d somehow missed before. Suppose you want to know whether a mask mandate will save lives during a pandemic. Current state of the art is to start two prediction markets: “conditional on there being a mask mandate, how many people will die?” and “conditional on there not being a mask mandate, how many people will die?” In this situation, this doesn’t work! Governments are more likely to resort to mask mandates in worlds where the pandemic is very bad. So you should probably predict a higher number of deaths for the mandate condition. But then confused policy-makers will interpret your prediction market as evidence that a mask mandate will cost lives.

(this is just the endogeneity problem, but for the future instead of the past!)

They admit that you’ve got to be really careful with this. If there are a lot of low-quality forecasters in the tournament, then since high-quality forecasters will accurately predict that low-quality forecasters will give a low-quality answer, everyone will converge on the low-quality answer. This paper is by Good Judgment Project who have just spent years identifying a population of superforecasters, so their plan is to use these people, who are all great, who all know they’re all great, who all know they all know they’re all great, etc. Philip Tetlock wasn’t writing all those books and tweets to self-aggrandize, he was writing them to create common knowledge!

They also admit this incentivizes teams to ignore “secret knowledge” that they have but which they expect other teams won’t. Their solution is to make teams very big and full of smart people, so that it’s unlikely other teams will miss something. I guess at the limit this is just banning insider trading, which is supposed to be good.

Their final concern is that you can just phone up the guy on the other team and say “We’re going to predict 7, if you also predict 7 then we’ll both win lots of money”. Their solution is multiple mostly-anonymous teams in online tournaments. I don’t know if this would survive a dedicated cheater, but I guess all tournaments are theoretically cheatable and most of the time they muddle through anyway.

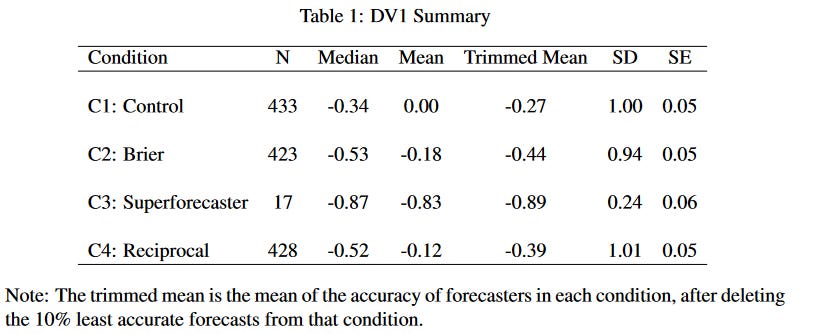

The paper continues to an empirical study. The authors ran a forecasting tournament on various easily-checkable things like COVID vaccinations, commodity prices, and the weather. Forecasters were separated into three conditions: reciprocal scoring, traditional scoring (ie Brier score + incentives), and no scoring. The no scoring team did worse than the normal scoring team, which is the basic insight Tetlock et al have found again and again: scored and incentivized forecasts are better than random people pontificating on things. But more relevantly for this paper, the reciprocal scoring and traditional scoring did basically the same!

More negative numbers means greater accuracy.

More negative numbers means greater accuracy.

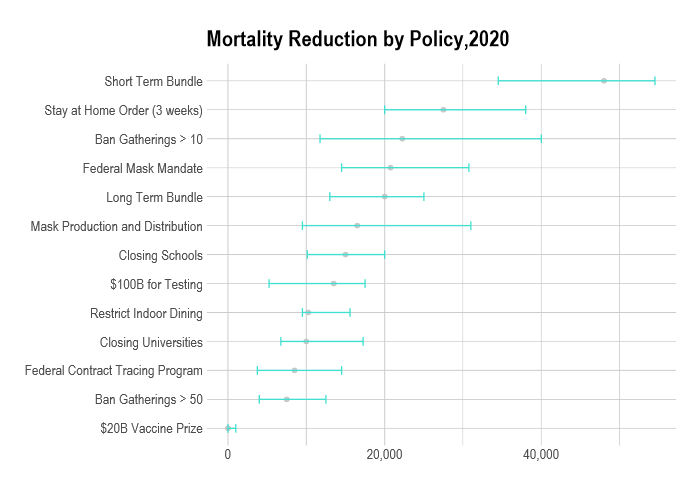

Then they tried something more ambitious. They asked teams to “predict” the number of lives saved by various COVID interventions. These interventions had already happened or not, there was no way to ever empirically resolve the predictions. This was supposed to serve as an example of the exciting new things you can do with reciprocal scoring.

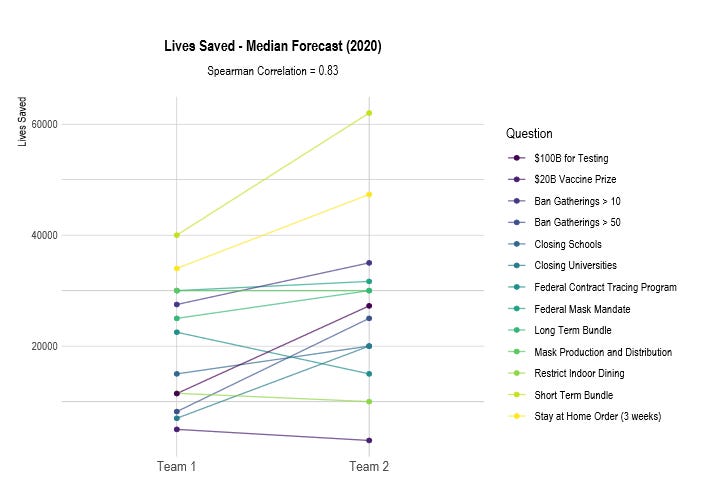

Both teams came up with pretty closely correlated estimates!

But are they correct?

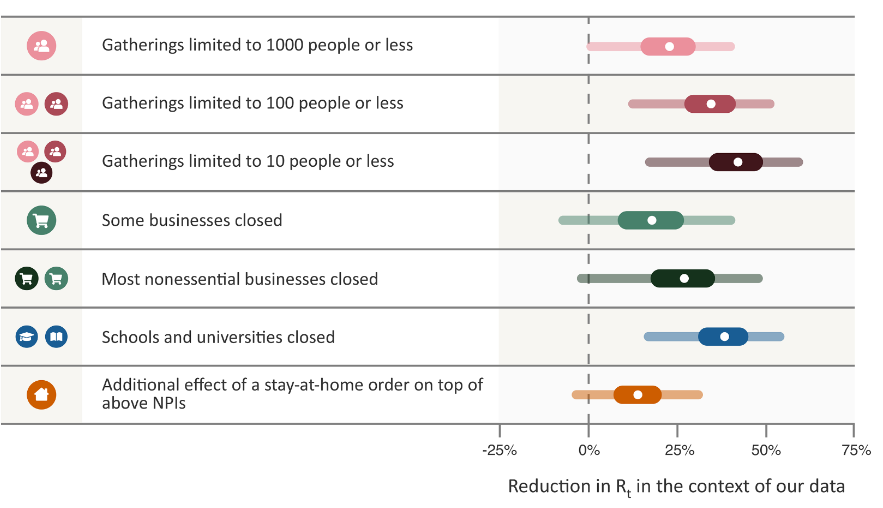

I looked into this myself a while back and decided the best paper out there was Brauner et al. The relevant part of their results was:

After comparing the two figures, I conclude…that you shouldn’t make a graph entirely in different shades of green, purple, and yellow. Do we have a better presentation of this? Yes? Okay:

Their categories are different enough from Brauner’s that I don’t want to say too much. The most obvious differences is that the forecasters are much more positive about stay-at-home orders than the scientists, but I think this is because the scientists are looking at additional value on top of restricting specific things, and the forecasters are looking at total value including the restrictions on specific things. Otherwise the rank order seems basically okay, idk.

(I also wouldn’t be too impressed even if the forecasters did get the same findings as Brauner et al, because one likely route to that would be the same one I took - you’ve resolved to judge various coronavirus interventions, you notice Brauner et al is clearly the best paper, and so you report its results.)

Overall, I’m really excited by this. My only concern is that it doesn’t have the same sort of hits-you-between-the-eyes obviously-there’s-no-way-to-bias-this quality that prediction markets do. If these people had predicted the effects of COVID restrictions before COVID, people would have doubted them for the same reason they doubted the ordinary experts.

“Too Close To Call”

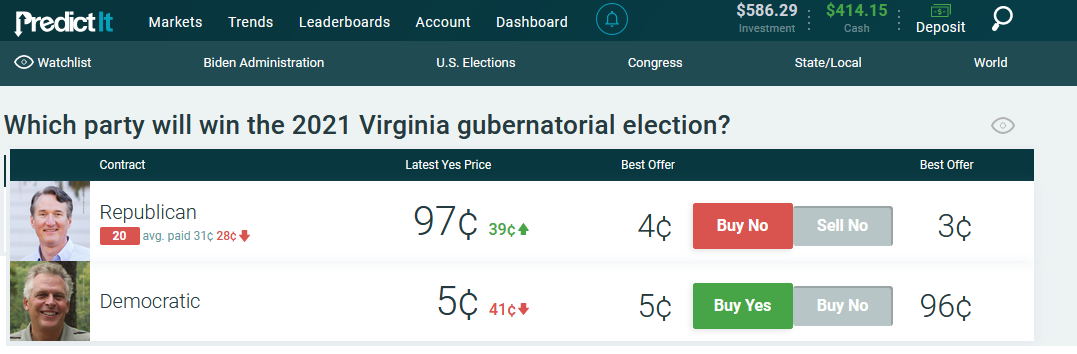

Here are some screenshots I took within a few moments of each other on the night of the Virginia election:

CNN: Tight race! Close contest!

PredictIt: 97% chance the Republican wins (he did)

NBC: Tight race! Too close to call!

Polymarket: 98% chance the Republican wins (he did)

You get the picture.

Prediction markets reached near-certainty about the winner while traditional media was still talking about how un-call-ably close it was. Apparently having hundreds of people all incentivized to give precise probability estimates very slightly earlier than the next guy, works better than having a few journalists who are scared people will make fun of them if they jump the gun.

Might prediction markets be lurching to a false certainty too soon? I used to think this, I tried betting on that thesis a bunch of times, and I always lost money. I guess realistically we can’t know for sure that they’re not overconfident until we’ve tested their 98% probability fifty times, but I nominate someone else to lose their money for the remaining 40-something experiments.

Iterated Prediction Markets

A comment on the last post:

Suppose you want to know whether America will have a higher GDP than China in 2100. You want to make a real prediction market about it, none of this newfangled “reciprocal scoring” stuff. But nobody will put their money in a prediction market for more than five years at a time, because even if you double your money, 100% return over eighty years is a bad investment.

Maybe you run a prediction market now, asking “what will people in 2026 think of this question?” People in 2026 will be at least as knowledgeable as people today, probably more since they’ll have five extra years of data. So this is equivalent to asking what they think people like them only a bit smarter will think, which is equivalent to asking what they think is true.

You can imagine chaining this. In 2095, you ask people to predict the actual answer. In 2090, you ask people to predict the value of the 2095 market on December 31, 2095. In 2085, you ask people to predict the value of the 2090 market on December 31, 2090. The chain ends with you putting a market on Polymarket tomorrow asking what the market will think on December 31, 2025. This should work.

But is this any different from a normal market? After all, a normal market open from now until 2100 is implicitly a prediction market on what people will think in 2025, since you can sell your shares in 2025 (or any other time) and cash out. So just run a single market for 80 years and save yourself the trouble, right?

I think the advantage of iterating it this way is that you can amplify small changes. Suppose that right now, the market thinks there’s a 50% chance that America will beat China in 2100. But I am a great economic analyst who knows things the market doesn’t, which allow me to determine that the real chance is 52%. Leaving money in a market for five years to make 4% return doesn’t sound great. So we could do something like make people bet on whether the 2025 market would be <40%, 40 - 45%, 45-50%, 50-55%, 55-60%, or >60%. This way if you’re even directionally right you can double your money in five years. I bet there are more clever mathematical ways to do this which would give you finer-grained resolution.

Problem: it seems like in 2025, you’ll have a prediction market for 2030 that will also have bins like that, and not a specific number. So you’d have to find a way to convert your bins into a number - which shouldn’t be hard, you can just assume each bin represents a vote for the midpoint of that bin and average it out. Right? Are there math issues here I haven’t thought of?

What happens if you don’t expect enough institutional continuity in your prediction market provider to actually run the 2095 market that everything else is based on? I think this also goes fine? If you expect the market provider to last until 2025, then it’s the 2025ers’ problem whether it lasts until 2030. If enough people decide it won’t, this should decrease liquidity but not necessarily distort the market.

This feels kind of like witchcraft, so feel free to tell me why it won’t work or is unnecessary.

(Another possibility is that it would work, but that the key piece is amplifying small variations, and you can do that better with idk leveraged trading or some weird mathematical formula or something.)

This Week In The Markets

Nothing too technically interesting here, just questions I’ve been curious about and now have an answer for.

I’m fascinated by how many people expect someone who is neither Biden nor Harris to win the Democratic nomination in 2024. Biden is down five cents since this summer without any new health problems (that I know about), and sitting presidents rarely get refused a renomination just because they’re unpopular. Maybe people think Biden’s age wouldn’t have mattered if he was popular, but as it is it’ll make a graceful excuse to convince him to sit out? I still think he’s undervalued.

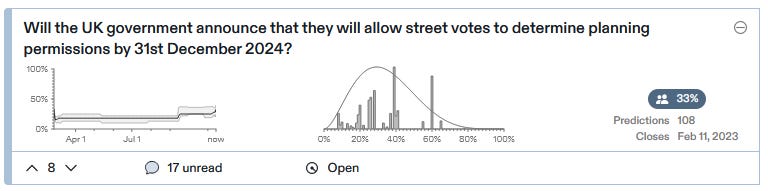

Some very unsurprising overlap between the Metaculus user and housing policy wonk populations here.

“Street votes to determine planning permissions” means that the residents of a single street - so maybe a two-to-three digit number of people - get to vote on their street’s zoning.

This is near the top of the YIMBY movement’s policy wishlist - they seem to think most people would vote for denser zoning, though I have trouble understanding their optimism. You can read their white paper arguing in favor here. As a bonus, it would probably lead to more attractive buildings, since people living next to a new development are more invested in avoiding eyesores.

(I’m not sure how blatantly developers are allowed to bribe citizens; I hope very blatantly indeed)

The policy seems to have some strong advocates in British government, and YIMBY leaders have offered probabilities like 50% or 60% that it’ll happen, which the market has sensibly downgraded to 33%.

I was wondering when this was going to show up; maybe it was too spicy for PredictIt and Metaculus. I’ve heard a lot of stuff about the prosecutor really bungling this one, but mostly from conservatives who I would have expected to hate the prosecutor anyway, so it’s good to get objective confirmation that yeah, this isn’t going anywhere.

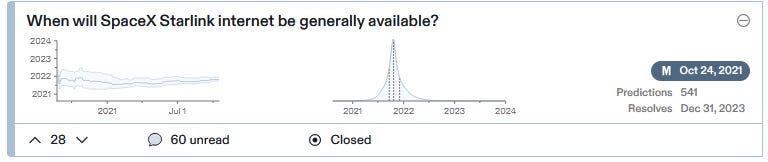

This prediction is in the past: Starlink became generally available last month! Somehow I missed it! But there’s a website where you can sign up and everything! Right now it’s only in select areas (it tells me it’ll be reaching the Bay in 2022-2023), but if you’re in those areas it’s available to normal people!

Also, Metaculus did a really good job with this one:

This shows their prediction over time. The final prediction was October 28th, which is unfair since the market still isn’t closed and you can just predict the date you know was correct. But even a year ago, people’s predictions basically got the right date within a couple of weeks. I don’t think there was anything obvious like Elon Musk saying “we’ll release on October 2021” (and it’s not like you trust a CEO who says something like that anyway!) AFAICT the market was just really good.

Shorts

1: Erik Hoel’s predictions for 2050. Recommended more than I would usually recommend this genre. I’ve been looking for really good new Substacks, by people I hadn’t already been reading for years on another platform, and this is one of the few I’ve found that I’m really excited about.

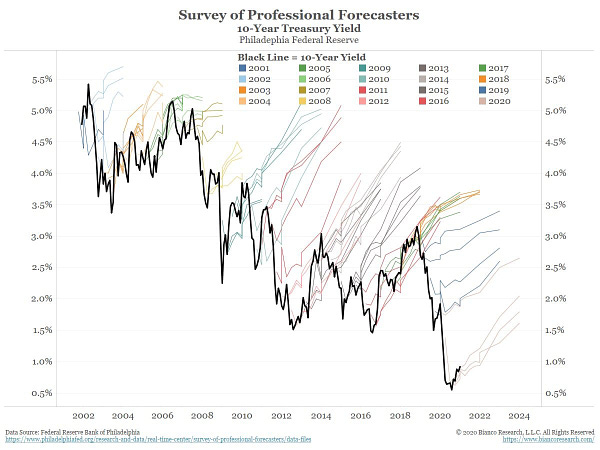

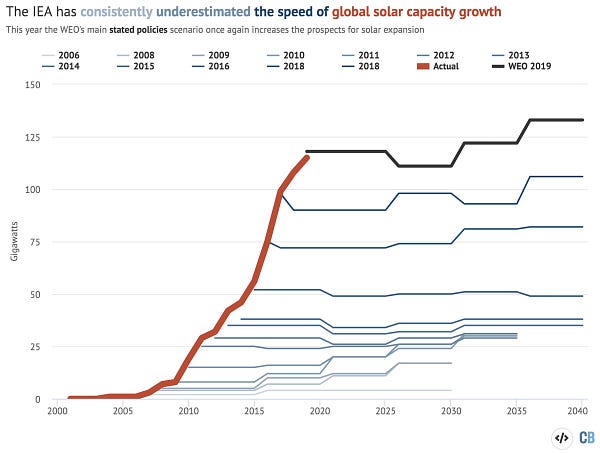

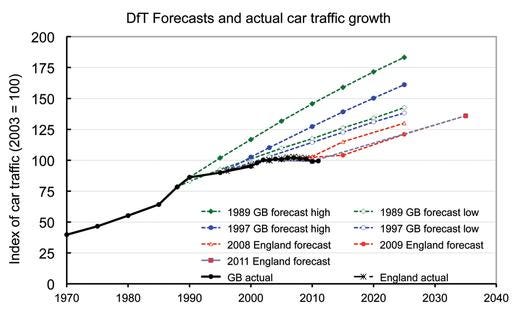

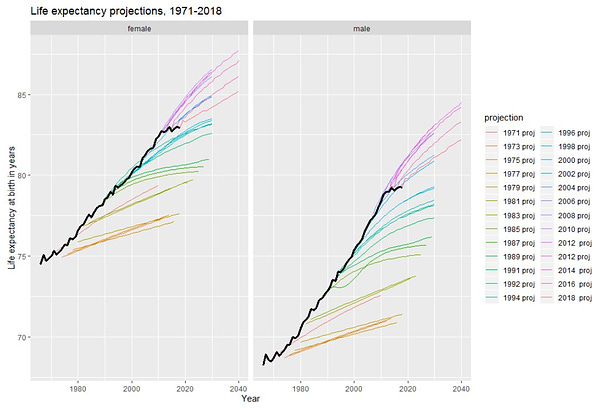

2: XiXiDu on times when expert forecasts were repeatedly wrong:

Alexander Kruel @XiXiDuExpert forecasts vs. reality

Alexander Kruel @XiXiDuExpert forecasts vs. reality

[12:49 PM ∙ Nov 1, 2021

[12:49 PM ∙ Nov 1, 2021

277Likes73Retweets](https://twitter.com/XiXiDu/status/1455155157977739265)

3: Reddit launches an on-platform predictions feature.