Mantic Monday 5/13/24

Disclaimer: This post involves more discussion of laws than usual. I am not a lawyer. Assume there are some errors. I will try to correct them after I learn about them.

CFTC Extra-Double-Bans Prediction Markets

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the body that thwarts real-money prediction markets, has announced that it will be thwarting them even harder from now on.

The proposed resolution is 17 CFR Part 40. It starts by explaining the current state of the law: the CFTC is allowed to regulate “events contracts”, ie predictions. The law says they should favor contracts about economic events (like “will interest rates go up”), and disfavor contracts about atrocities or gaming (like “will there be a terrorist attack?” or “will the Yankees win the World Series?”). Everything else - the bread and butter of prediction markets - is in a gray zone that the CFTC has to review on a case-by-case basis.

The new resolution says that, if you think about it, elections and awards ceremonies are kind of like gaming (they’re a competition and you’re betting on the winners). And they’re more likely to be bet on by gamblers than by people with legitimate financial motives. So the CFTC is moving them out of the gray zone and prohibiting them by default.

Does this change much? The CFTC already prohibited these in practice - they were in the ask-for-permission gray zone, but whenever someone asked them for permission, they said no. The only semi-exception was PredictIt, which was small enough and established enough that they got grandfathered in; the CFTC tried to go after them, but got bogged down enough in the courts that PredictIt isn’t quite dead yet. So on a first read, this slightly strengthens the CFTC’s case against PredictIt, tells everyone else to give up hope, but doesn’t really alter the landscape.

I think the biggest change is that it saves the CFTC time. They’re pretty open about this as a motive:

From 2006-2020, [designated contract markets] listed for trading an average of approximately five event contracts per year. In 2021, this number increased to 131, and the number of newly-listed event contracts per year has remained at a similar level in subsequent years

They especially don’t want to have to be forced to investigation elections:

If trading was permitted on CFTC-registered exchanges in event contracts that involve the staking or risking of something of value on a political contest, then the Commission could find itself investigating the outcome of an election itself.

I think their thought process is: if you manipulate the commodity markets by (for example) saying that you have lots of nickel when you don’t, the CFTC has to investigate that and penalize the people responsible. In a hypothetical world with election contracts, if someone manipulated an election - for example, they put out a fake poll showing that the incumbent would definitely win so there’s no point in even voting - someone could ask the CFTC to investigate.

I don’t know if I like the idea of federal agencies banning things because, if they were allowed, it would create more work for the federal agency. Imagine if the medical regulators banned surgery, because otherwise some surgeons might be accused of malpractice, but the malpractice lawyers want to go home early on Fridays.

Otherwise, I’ll just reiterate the same points everyone made last time they tried this:

-

The UK has election betting and none of these negative outcomes have come to pass.

-

There are already hundreds of groups that care deeply about the outcome of elections. Some have billions of dollars on the line, like defense contractors, fossil fuel companies, real estate developers, and investment banks. Others care for non-financial reasons: transgender people, Christians, gun owners, the population of Ukraine, people who think we’ll all die from climate change, people who think the country will become a dictatorship, all Democrats, all Republicans, etc. The idea that adding one more group - “people who have a few thousand dollars staked on Kalshi” - will be the difference between a safe and secure election, and one that’s hacked by motivated parties, is pretty crazy.

-

Although most election bettors right now are degenerate gamblers, that’s a result of the CFTC making it hard, not an excuse for them to make it harder. If the CFTC got out of the way and let people bet 7-digit-sums on this legally, most election bettors would probably be the groups mentioned above (defense contractors, fossil fuel companies, etc) trying to hedge their risk. These groups have billions of dollars in risk, which is probably enough to overwhelm however much money the degenerates can gather.

And a few extra points:

-

Trying to weasel out of this by classifying elections as a sport is pathetic. Are you going to let colleges count anybody who runs for student government against their Title IX requirements? No? Seems like you’re not really serious about this “elections are a sport” thing.

-

If someone tries to manipulate nickel futures by blowing up a nickel mine, I think (I’m not an expert) this the the FBI’s problem, not the CFTC’s. In the same way, I would hope a regulatory framework could be developed that would investigate election fraud without making it the CFTC’s problem. Given that there’s already a big incentive for all the groups named above to manipulate elections in various ways, I would hope that some framework like this already exists.

Anyway, although this is dumb, I don’t think it changes facts on the ground very much. Some possible exceptions:

-

RIP Kalshi, who are the main group negatively affected by this. This takes away a lot (though not all) of their value proposition, leaving them the option of contracts on some economic indicators, weather, and whatever else they can slip through the cracks.

-

Polymarket and Insight already IP ban US users and claim not to be operating in the US, so they shouldn’t be directly affected. But it might alter some case tangentially involving them one way or another.

-

This will probably have some effect on PredictIt’s legal case, but I can’t predict exactly what.

-

Probably no effect on Manifold’s pivot, see below.

See also:

-

Maxim Lott’s article on this for more information, including the chances that this gets tied up in the courts.

-

Statement by the CFTC chairman on why he supports this.

-

Statements by two dissenting CFTC commissioners (1, 2) on why they oppose.

Pivotal Act

Manifold Markets says they’re pivoting to a new model combining play money points and real-money gambling.

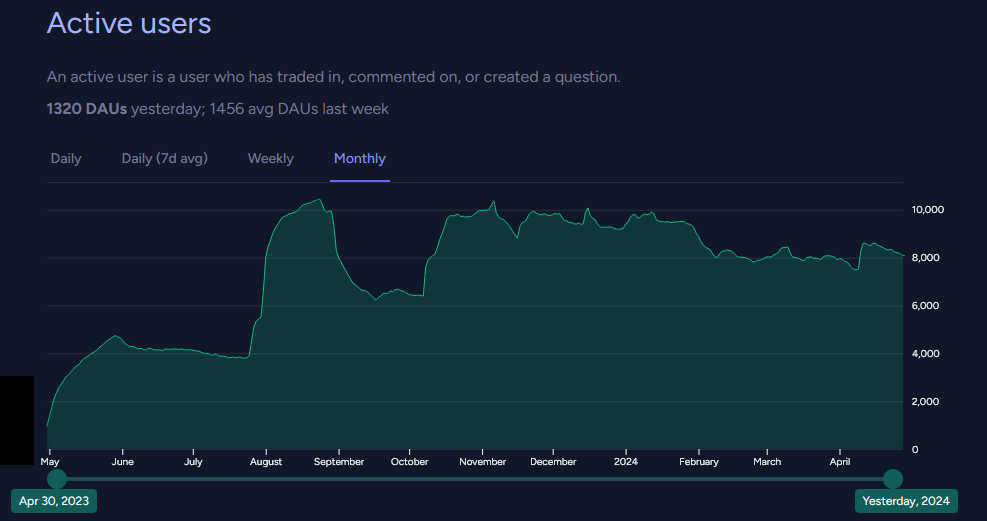

Manifold may be a beloved local fixture, but their growth and revenue aren’t too impressive:

In the interests of continuing to exist and push prediction markets forward, they will switch to a “sweepstakes” model.

Although gambling is illegal in most US states and requires complicated licensing in others, there’s a “sweepstakes loophole”; companies are allowed to offer “prize sweepstakes”, and you can use this to sort of reconstruct the concept of gambling in a legal way. You don’t give the company money and get back money. You pay for “points”, get “sweepstakes tokens” as a bonus, gamble the “sweepstakes tokens”, and then cash in the sweepstakes tokens for money. This is a pretty surprising loophole, but it’s already used by sites like Chumba Casino and Fliff.

(and apparently it creates weird incentives! In order to maintain the fiction of being a “sweepstakes”, these casinos have to give you “tokens” if you request them by mail. If you send a postcard to Chumba Casino asking for free money, they’ll give it to you, $5 per postcard. Is this an infinite free money pump? My impression is in theory yes, but the postcards have to be handwritten in a very specific way, the company sometimes rejects them for weird reasons, the cost of materials and mailing lowers your profit to more like $4, and so you’d have to hand-write 250 postcards to make $1,000. I’m still surprised more people don’t do this.)

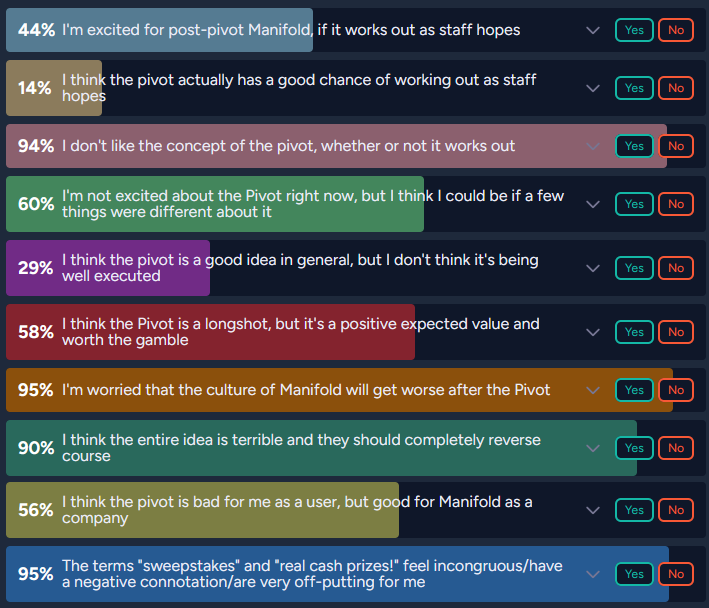

Because real money is involved, Manifold will have to tighten the rules on markets, including banning N/A resolutions. You can see a full list of changes here. Manifold users are split between acknowledging that the for-profit company they love needs some way to make money, being salty about the changes, and being worried that creating more of a casino atmosphere will be bad for users / the world / ability to function as a good prediction market.

(I understand most of the NO vote here is based on the theory that there will be legal intervention - maybe because the government is willing to tolerate sweepstakes casinos but not sweepstakes prediction markets).

Manifold co-founder Austin Chen won’t be involved. He’s leaving the site - not explicitly because of the pivot, he just said it seems to be “trapped in local optima”. He plans to focus on other parts of the Manifold empire, especially Manifund, which tests impact markets, regranting, and other “experimental” charity models.

Manifold will continue in the hands of the other two co-founders, James and Stephen Grugett.

Superhindcasting

I mentioned this in my lab leak post, but it deserves more attention here: Good Judgment Project’s report on Superforecasting The Origins Of The COVID-19 Pandemic.

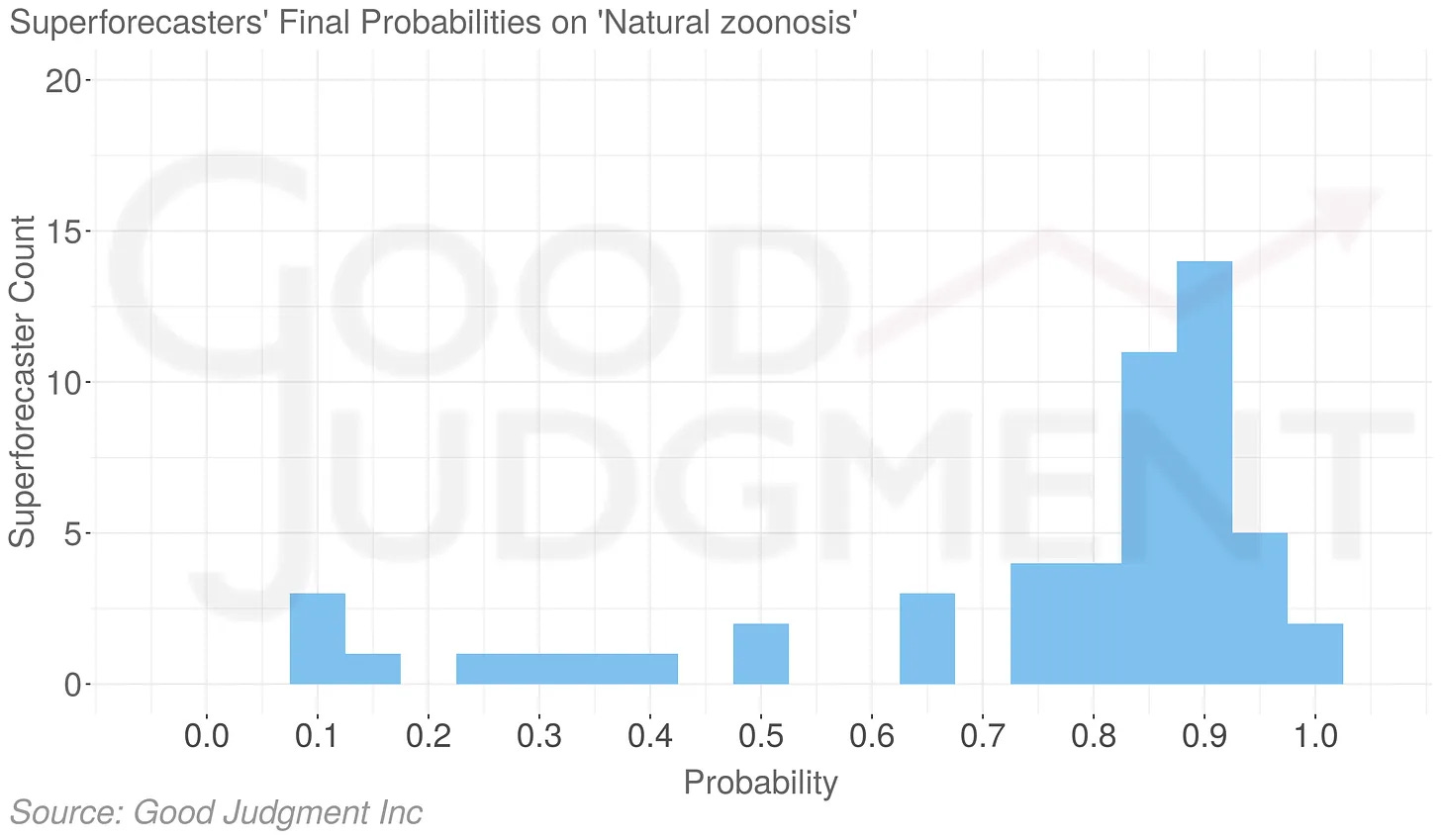

Good Judgment Project employs superforecasters who will predict things for clients. Some people interested in COVID origins asked them to judge whether lab leak was plausible. Their headline result was 74% zoonosis, 25% lab leak, 1% something else.

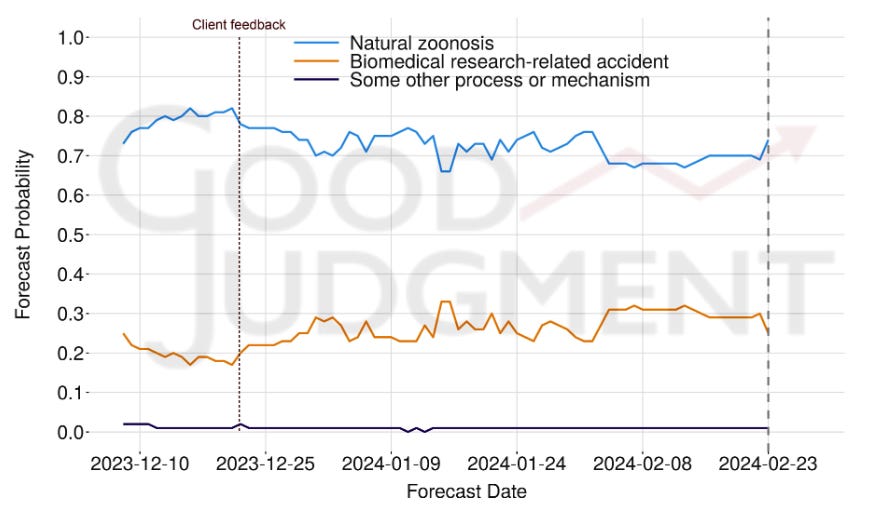

Part of GJP’s method is getting their forecasters to share sources and talk to each other. Here’s the graph for how that went:

People changed their minds a little over time, but not in a very consistent way that mattered much in the end.

What was the “client feedback”? The report says:

Client feedback was provided to the Superforecasters on December 21. The client posed questions to the Superforecasters about their assessments up to that date and asked for their reactions to several studies and articles. In the days following the client engagement, the Superforecasters lowered their confidence in the natural zoonosis hypothesis from 73% to 67%, although zoonosis remained the most likely potential cause in their assessment. But following an active engagement with recent genomic studies and historical base rates of zoonotic spillovers, those numbers began to return to earlier levels. January also saw increased attention to the geopolitical context and transparency issues, particularly related to research activities in Wuhan

Is this bad? I’m imagining a pro-lab-leak client saying “But what about [this list of pro-lab-leak arguments]?” and then the superforecasters read them and adjust. In one sense, it’s good that they got to see more arguments; on the other, it seems like a potential route by which clients could bias the results - probabilities never quite got back to where they were before the feedback, though they got pretty close. The last-minute spike for zoonosis might be the Rootclaim debate results, which were released on 2/18.

So maybe the client feedback and the Rootclaim results both slightly affected the numbers, but mostly the superforecasters started out pro-zoonosis and stuck to their guns.

Dan Schwarz and the FutureSearch team say that forecasting has a “rationale-shaped hole”. Despite the report making this sound like a pretty intense process, we don’t get much information about details:

In their extensive discussions , Good Judgment’s Superforecasters assessed base rates and historical patterns, existing evidence and scientific analysis, geopolitical context and transparency concerns, trust in intelligence communities, and methodological constraints.

1. Base Rates and Historical Patterns: The Superforecasters frequently referenced base rates, i.e., the history of pandemics emerging from natural zoonosis versus the history of laboratory leaks, to anchor their probabilities. For the former, they discussed how the base rates are changing as the climate warms and as expanding human populations push farther into natural environments that previously saw little human presence. For the latter, they acknowledged that it has only been 12 years since the advent of CRISPR gene- editing tools, and the base rate of lab leaks in the short synthetic biology era is not yet well established.

2. New Evidence and Scientific Analysis: Throughout the period, the Superforecasters adapted their forecasts in light of new scientific evidence, including genomic analyses of SARS-CoV-2 and its relation to bat viruses, and the debate over potential laboratory manipulation.

3. Geopolitical Context and Transparency Concerns: The geopolitical implications of the virus’s origins, particularly in relation to China’s transparency and the involvement of international research institutions, played a significant role in the analysis. Concerns over data veracity, and over the political ramifications of determining that the pandemic’s origins were other than zoonosis, were extensively debated.

4. Trust in Intelligence: Commentary on trust in intelligence communities and discussions about the impact of geopolitical biases on the interpretation of evidence illustrated the complex interplay between science, politics, and human behavior in assessing the pandemic’s origins.

5. Methodological Critiques and the Evaluation of Evidence: The Superforecasters engaged in methodological critiques of the evidence base, including the scrutiny of laboratory practices and biocontainment levels […]

In the end, most Superforecasters were in rough agreement on issues like the base rates of zoonotic spillover. Where they most often disagreed was on the interpretation of actions by Chinese officials and whether their actions reflected how an authoritarian government would react in any crisis over which it did not have full control, or whether those actions were indicative of attempts to cover up a biomedical research-related accident that allowed the SARS-CoV-2 virus to enter circulation in China and, ultimately, the entire globe.

Probably it would be too much to ask for to get a transcript of all their discussions - then they’d be nervous saying things that might make them look bad to an audience. What would be a good balance between getting more information and not imposing on their time?

Forecasting is an unusually legible and easy-to-judge domain. One of the theories of change for forecasting was to use it to identify smart people with good reasoning, then turn them loose on less well-behaved problems. This is one of the first big attempts to do this at scale. How did it work? We can’t tell, because it’s inherently an illegible and hard-to-judge domain. Darn. I don’t know what I expected.

Notes From A Local Optimum

Austin’s concern - that forecasting has reached a local optimum - is widely shared. We have some good sites: Manifold, Metaculus, Polymarket, GJO, etc - all doing good work. We have good-ish probabilities for a few important questions. Every so often a news source cites them. Sometimes a decision-maker looks at them behind the scenes, maybe. Is this all there is?

The FutureSearch team says the next step is to focus on “rationale”. We need to use forecasting not just to get a raw probability, but to explain what’s going on and why we think something. Then instead of just convincing policy-makers to trust forecasts, we can tell them why something is true, or inform their discussions even if they’re not willing to blindly trust a number. Is this a betrayal of the forecasting ethos? The original dream was that instead of a bunch of people giving arguments, we could just test who was right. Now we’re going back to the arguments? People have argued forever; what does forecasting add to that? Well, they add the knowledge that the arguments are from people who have been right a lot before and are incentivized to be right again. Still, it’s not a natural fit. Probably it’s relevant here that FutureSearch’s forecasting AI does a really good job of this by default, in a way humans can’t match.

Nuno’s yearly forecasting roundup doesn’t have a single thesis, but the first part is a well-supported complaint that most forecasting sites aren’t good business. They either burn VC money, burn EA donations, or converge towards casinos to support themselves. He gives an honorable exception to Cultivate Labs, which sells prediction market software rather than the results themselves.

Open Philanthropy (billionaire Dustin Moskovitz’s EA-aligned charitable foundation) has at least given forecasting a vote of confidence, recently choosing to promote it to one of their main donation areas. Still, they got a lot of pushback on the decision, for example SuperDuperForecasting here:

This will be a total waste of time and money unless OpenPhil actually pushes the people it funds towards achieving real-world impact. The typical pattern in the past has been to launch yet another forecasting tournament to try to find better forecasts and forecasters. No one cares, we already know how to do this since at least 2012!

The unsolved problem is translating the research into real-world impact. Does the Forecasting Research Institute have any actual commercial paying clients? What is Metaculus’s revenue from actual clients rather than grants? Who are they working with and where is the evidence that they are helping high-stakes decision makers improve their thought processes?

Incidentally, I note that forecasting is not actually successful even within EA at changing anything: superforecasters are generally far more relaxed about Xrisk than the median EA, but has this made any kind of difference to how EA spends its money? It seems very unlikely.

And Marcus Abramovich here:

I’m in the process of writing up my thoughts on forecasting in general and particularly EA’s reverence for forecasting but I feel, similar to @Grayden that forecasting is a game that is nearly perfectly designed to distract EAs from useful things. It’s a combination of winning, being right when others are wrong and seemingly useful, all wrapped into a fun game.

I’d like to see tangible benefits to more broad funding of forecasting that seems to be done in t he millions and tens of millions of dollars.

I would also be the type of person you would think would be a greater fan of forecasting. I’m the number one forecaster on Manifold and I’ve made tens of thousands of dollars on Polymarket. But I think we should start to think of forecasting as more of a game that EAs like to play, something like Magic the Gathering that is fun and has some relations to useful things but isn’t really useful by itself.

Eli Lifland has a long and hard-to-summarize comment here, response from Ozzie Gooen here, podcast between them on “Is Forecasting A Promising EA Cause Area?” here.

I’m split on this. My previous hope was that the field would gradually grow, without any qualitative changes or discontinuities, until it became big enough that journalists and policy-makers were aware of it and took it seriously (compare eg the growth of the Internet as a scholarly resource). I think the strongest argument against this is Manifold’s relatively flat user numbers.

Is there a new hope? I think if nothing else, forecasting might be useful as a testing ground:

-

First, to create forecasting AIs (like FutureSearch) which can then get consulted on a variety of questions, eg by policy-makers. The biggest holdup has always been the need to gather 20 or 50 or however many hard-to-find superforecasters for whatever question you’re asking, and then trust their advice even though they’re fallible fleshbag humans. If you can use the 20 to 50 superforecasters to inspire an AI, and then test the AI and prove it’s good, people might be more interested. This is especially true if the AI can branch out beyond traditional forecasting questions. Once we have a few of these, we can start comparing the next generation of AIs to the previous generation, and skip the superforecasters.

-

Second, to identify smart people, who can then be asked to solve problems outside of traditional forecasting domains (eg “Tell me all the ways this could go wrong, and which are the most likely”).

But this is a pretty limited vision, and a time-limited one (once we’ve done these things, why keep putting the millions of dollars in?)

I still maintain some hope that someone will find the killer app that makes forecasting explode, but I don’t know what it would be.

One bright spot: both DeepMind (see 8) and OpenAI (see 2.12) recently hired forecasters (Swift Centre for DeepMind, OpenAI still keeping details secret) to predict some features of their AI models. I think this is cool, but it probably owes more to there being a bunch of rationalists at those companies (and rationalists loving forecasting) than to any sign of broader commercial adoption.

This Month In The Markets

Nate Silver, Josh Barro, and others have been banging this drum recently: the most important thing Democrats can do this year is get Sonia Sotomayor to retire. Sotomayor is an older liberal-leaning Supreme Court justice. She might get sick or die in the next four years, and if Republicans win the 2024 election, then they get to choose her replacement and the Court shifts even further right. If she retired today, Biden and the Democratic Senate would choose her replacement and the Court wouldn’t shift. She doesn’t want to resign, but Silver (remembering the similar case of RBG) thinks Democrats should pressure her as best they can. The markets have been shifting between 20% and 40%, but don’t seem to expect this to happen.

Kind of feel like I should be hearing more about this.

Bibi must have sold his soul to the Devil or something, I cannot believe he’s going to make it through this.

This is a response to the predictions I made in my update on the Lumina probiotic. You can click “see three more answers” for the question on side effects (separate from this question on efficacy). My numbers were 5/35/10/50 for the first question and 30/5/<1 for the second.

Huh?

Okay, so there are at least three cases. There’s paying Stormy Daniels hush money, currently going on in New York. There’s a Georgia election interference case. And there’s a federal election interference / January 6th case.

The Supreme Court recently said there were so many presidential immunity issues that it’s going to take forever to start trying the federal case, which is why that one is at 20%.

The New York case is going on now, and it seems like there’s an 80% chance he’ll be found guilty. The part I don’t understand is the last one (73% found guilty of felony in New York) vs. the second one (56% of any felony at all). This might just be a failure of arbitrage. It looks like nobody expects jail time in any case.

Here’s an embarrassing screwup from Metaculus. This question was about when there would be a “Great Power war”, with Great Powers defined as any country in the top ten of military spending. But surprise surprise, Ukraine getting invaded made them spend a lot of money on their military that year, so they rose to #8 in the world in military spending in 2023. Since Russia is also in the top ten, this qualifies as a “Great Power war” by the technical definition, and the question resolves positive. Moral of the story: resolution criteria are hard!

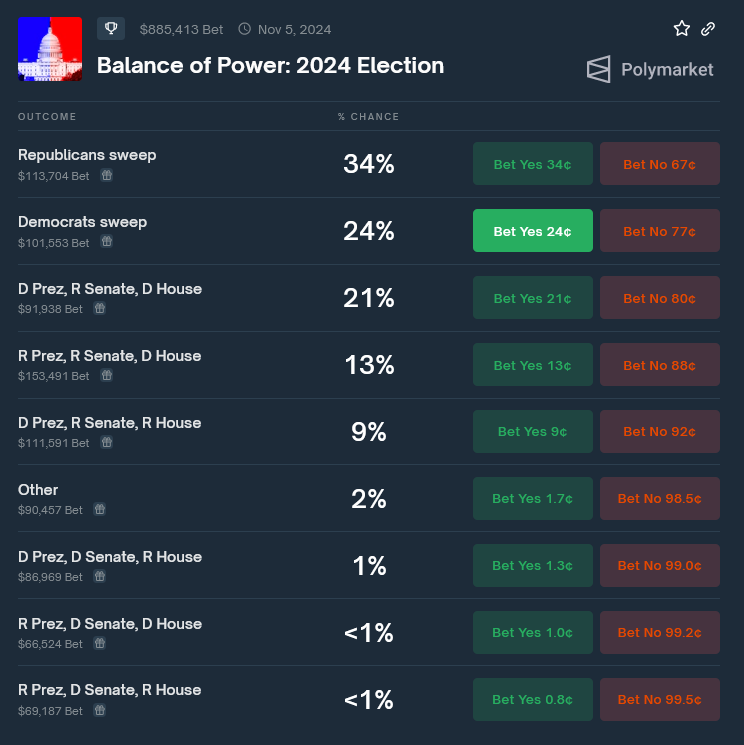

Polymarket on 2024 election results. In the past they’ve had a Republican bias, but now their Presidential markets are in tune with everyone else in the polls, so maybe this is accurate.

Forecasting Links

1:Swift Centre forecasts that global coal consumption will stay high, despite the standard line that it will decline as cleaner energy comes on line. This is a rare case where superforecasters take a clear position opposed to a mainstream consensus, so I look forward to grading it later.

2:TimeGPT is supposedly a revolution in “time series forecasting”. I don’t know enough about this field to have an opinion.

3: Kiko Llaneras of Spanish media EL PAIS is hosting an elections forecasting tournament on Metaculus.

4:Limitless is the latest attempt at a crypto prediction market. I don’t know why they expect to succeed when the last n has failed, but people are betting 51% odds of $10 million volume in their first year.

5: Manifest, the prediction market conference, is still in Berkeley this June, see here for more information.