Mantic Monday 5/22/23

Whales Vs. Minnows Goes Wrong

Manifold is a play money prediction market. Its intended purpose is to have fun and estimate the probabilities of important events. But instead of betting on important events, you might choose to speculate on trivialities. And instead of having fun, you might choose to ruin your life.

From the beginning, there were joke markets like “Will at least 100 people bet on this market?” or “Will this market’s probability end in an even number?” While serious people worked on increasingly sophisticated estimation mechanisms for world events, pranksters worked on increasingly convoluted jokes. In early April, power user Is. started “Whales Vs. Minnows”: Will traders hold at least 10000x as many YES shares as there are traders holding NO shares? In other words, Team Whale had to sink lots of mana (play money) into the market, and Team Minnow had to get lots of people to participate.

Team Minnow started cheating first. They rounded up their friends and asked them to register Manifold accounts and join the market. This might have been semi-fair to start, but then they started paying people, in real money, to do it. Team Whale - mostly Is. - figured out some cheats of their own, which you can read about here.

Manifold allows users to spend real money to buy play money. Not too many people do - there’s not much to do with it - but they keep the option open for people who want to support their site. After the cheating had escalated a bit, Is. cut out the middleman and just started buying mana. Every time the Minnows recruited new people, Is. bought more mana with real money.

One thing led to another and Is. sunk $29,000 of real money into the market. This would have been a bad plan even if he won. There is no way to convert mana winnings back into dollars. All he would have gotten was a giant pile of play money and bragging rights. But in fact, he did not win.

It turned out he was not a tech billionaire with unlimited money to spend. He was just an ordinary guy throwing a substantial amount of his money into this market. When he ran out of money he could commit, he lost.

This is a pretty crazy thing to do. But someone compared it to a dollar auction - a known strategy for making people do crazy things. In a dollar auction, some prankster auctions off a dollar to the highest bidder. The catch is that everyone has to pay their bid, whether they win or not. So maybe someone bids $0.50, thinking they’ll make a free 50 cents. Then someone else bids $0.90, thinking they’ll make a free 10 cents. Then Bidder #1 realizes that they’ll lose 50 cents unless they get the dollar, and bids up to $1.00 so they can at least break even. Bidder #2 realizes they’ll lose 90 cents unless they get the dollar, so they bid up to $1.10 so they can at least only lose ten cents. Soon #1 is at $99.50 and #2 is at $99.75, and #1 figures he might as well escalate to $100 so he can lose only $99 instead of $99.50 . . .

Manifold had assumed they didn’t have to worry about compulsive gambling. Their site is free. You can buy mana, but you can’t trade it for real-world goods. There’s no way to win real money. Doesn’t seem like a recipe for disaster. But apparently this was optimistic. The thrill of winning a pointless prank market, and the pull of throwing good money after bad, are all that some people need.

Everyone was pretty horrified, so after a few days of thought Manifold founder Austin Chen announced that they would:

-

Refund Is. $25,000 of his $29,000 loss, with the remainder “acting as a disincentive”.

-

Remove the ability to buy more than $100 of mana at a time.

-

Take various actions to incentivize markets that predict world events, and disincentivize “will this market do X?” style gambling. For example, mana won in gambling markets will no longer count towards the leaderboard, and they’ll no longer show as “trending” on the front page.

Manifold is in an awkward place. Like many early-stage websites, they have an enthusiastic community, a great product, and not much plan for making money. Their stopgap strategy was to let people buy extra mana with real money. They don’t want to remove this option, because it’s their whole business plan. But it’s a weird thing to do. Some fraction of the people who do it will do it for the wrong reasons. Manifold made the right choice refunding most of the money and taking steps to prevent this from happening in the future. But it was still a challenge the idea that it’s possible to run any kind of gambling-adjacent institution ethically, no matter how careful you try to be.

I recently read an article on Sean McElwee, a recently-cancelled Democratic pollster. McElwee got in trouble for lots of reasons, but one was a gambling addiction, and one of the places he gambled was prediction markets (the article doesn’t say which one, but I assume it was PredictIt, the only America-accessible political prediction market that takes real money). PredictIt limits users to a few hundred dollars per wager, this clearly wasn’t the bulk of his gambling problem, and he seemed to do pretty well (his problem wasn’t he lost money, his problem was that he got in trouble for betting on elections that his polls influenced).

And I don’t want to exaggerate how worried to be about this. People lose way more money on sports betting and poker every hour. A site that produces lots of great information, raises the sanity waterline, and once a year or so causes someone to lose $29,000 which management immediately gives back because they feel bad - is hardly the face of problem gambling in America.

But still, now this is a thing that sometimes happens.

Debt Brinksmanship

Speaking of people ruining lives with bad financial choices - Congress is debating raising the debt ceiling. If they can’t compromise, the US will default on its debt, with potentially severe economic repercussions. But usually both parties do some brinksmanship but then compromise at the last moment. Will that happen this time too?

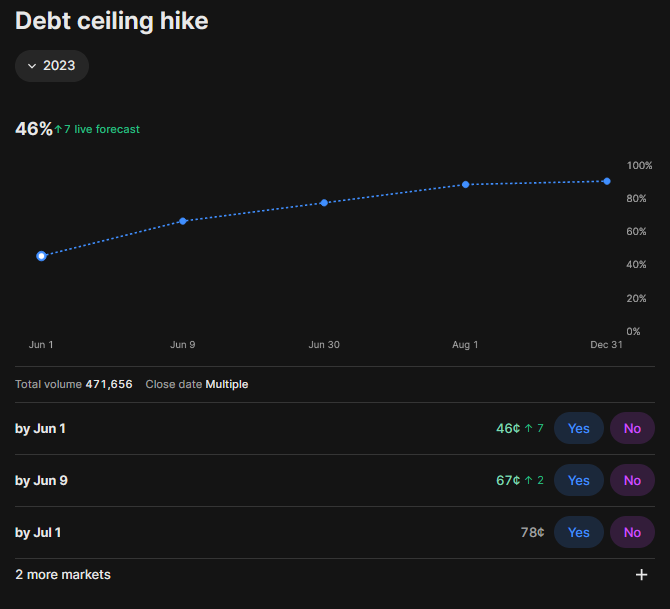

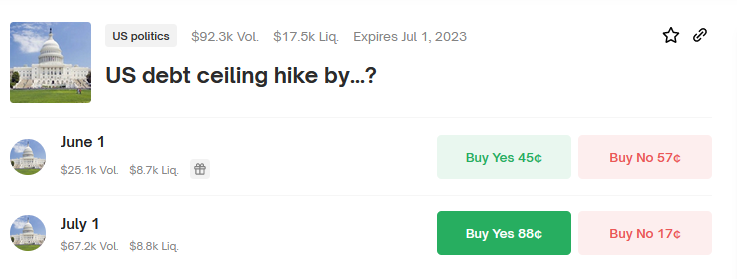

All three sites think the most likely outcome is that the US successfully raises the debt ceiling (Metaculus is lower than the other two, maybe because it asks about a shorter time period).

But when? From Kalshi and Polymarket:

What happens if they don’t? The White House report says a “protracted” default (ie for more than three months) could sink the stock market by 45%. Is this an exaggeration?

Given that this is about any default, and not just a “protracted” one, I think this backs up the White House claim that this would be pretty catastrophic.

EPJ Probes The Long Run

Superforecasters are pretty good at telling you who will win next month’s sports game, next month’s election, or next year’s geopolitical clash. What about the longer-term? Can they predict broader political trends? The distant future of AI? Until now, we didn’t know, for a simple reason: superforecasting was only a few decades old. Philip Tetlock did the original Expert Political Judgment experiments in the 80s and 90s.

In a predictive success of his own, Tetlock realized this would be a problem early on. In 1998, he got experts to make predictions for the next 25 years. Specifically, he asked his forecasters to predict the course of nuclear proliferation and various border conflicts. Some were geopolitics scholars were were experts in these fields; others weren’t. It’s been 25 years since 1998, so we’re ready to open the time capsule and see how they did.

Before answering: how do we judge the results? That is, the subjects made some guesses about the world in 2023. Let’s say a third of them were right. Is that good or bad? Does it mean people can predict the future 25 years out, or they can’t?

Tetlock proposes several specific questions, of which I’ll focus on the three I find most interesting:

-

Will forecasters do better than some hacked-together algorithmic guess based on base rates? For example, if we ask “will countries X and Y go to war in the next 25 years?”, will experts outperform just guessing the base rate of war between those two countries (or two similar countries) over a 25-year-period?

-

Will experts do better than non-experts?

-

Will wisdom of crowds work? That is, will the aggregate of all forecasters beat most individual forecasters?

The paper finds:

-

Yes, forecasters beat base rates by a small amount (d = ~0.25) even at the 25 year distance.

-

Sort of. Experts beat non-experts on nuclear proliferation (d = ~0.40), but not on border conflicts. One possible explanation is that nuclear proliferation experts are good and real but border conflict experts are bad and fake. But another explanation is that the last twenty-five years of nuclear proliferation was “well-behaved” and followed popular theories, and the last twenty-five years of border conflicts were anomalous.

-

Yes, the wisdom-of-crowds aggregate beat all individual forecasters when considering the entire time period; looking only at the 25-year-out-predictions, it beat almost all individual forecasters.

So does this mean skeptics were wrong, and long-range forecasting is definitely possible? The paper’s discussion section is ambivalent:

Meliorists can now claim systematic evidence for long-range geopolitical forecasting skill, an elusive phenomenon that some Skeptics had declared impossible (Taleb & Blyth, 2013) and one for which all previous evidence was anecdotal. Proliferation experts beat both well-educated generalists and base-rate extrapolation across time on the key empirical-accuracy indicator: they assigned higher probabilities when proliferation occurred—and lower values when it did not. Achieving a higher Hit rate at a lower False-Alarm rate proves proliferation experts were not indiscriminately crying wolf. Experts’ edge even held across controversy and close-call-counterfactual challenges to accuracy scores, which blunts the flukiness-of-history objection. Moreover, proliferation experts did better on logical-coherence indicators. Their judgments were more scope sensitive and aligned with the normative model for compounding cumulative risk. And they did all of this under far-from-ideal conditions: making rapid-fire judgments, about one nation-state per minute. They drew on insights more accessible to epistemic-community insiders than to outsiders—a hallmark of genuine expertise.

A natural next question is: How much should Radical Skeptics change their minds? But that question is premature. The findings did not always break against them. Expertise failed to translate into accuracy on over half of the questions: those on border-change/secession. Moreover, the data are limited to a narrow slice of history—and the questions posed a deliberately biased sample from the universe of possible questions: slow-motion variables chosen to give forecasters a fighting chance. It is unwise to draw sweeping conclusions from so wobbly an evidentiary base. Whatever long-range predictability emerged is due to loading the methodological dice: posing easy questions in a placid period of history.

Each side is now armed with talking points: Meliorists with a proof-of-concept demonstration and Skeptics with reasons for debunking it. We could call it a draw. But that would also be too facile. The problems run deeper than a debate over a dataset. The debate itself is flawed. Each school of thought has too many conceptual degrees of freedom for neutralizing disagreeable findings. Each can stalemate debates over virtually any dataset. That is why we need an unusually long Discussion section that resets ground rules.

The Discussion section is indeed very long. Its gist is that this shows one example of forecasters doing well. It doesn’t seem to just be luck, because (for example) experts’ estimates were more mathematically coherent (eg the risk of a border conflict over 10 years should be higher than over 5), but it could have been partly luck. But this was a pretty easy task in various ways. If people disagree that this has relevance to real-world long-range forecasting, they should make specific testable claims about what would constitute the sort of real-world long-range forecasts that they think experts can’t do, and what would constitute a fair test of whether experts were able to do it. Then researchers can do adversarial collaborations to see whether experts can do those things.

I interpret this as: it’s tempting to treat this as Team Long-Range-Forecasting-Is-Possible Vs. Team No-It-Isn’t. But everyone agrees certain kinds of long-range forecasts are possible (I predict with high confidence that the US President in 2050 will not be a Zoroastrian) and others are impossible (I cannot begin to predict the name of the US President in 2050). People who consider themselves “believers” vs. “skeptics” about long-range forecasting should figure out the exact boundary of which cases they disagree on. And then Tetlock et al can test those cases and figure out who’s right.

Balaji’s Big Bitcoin Bet

What’s the role of bets in forecasting? Prediction markets are their own thing, but in general a bet acts as a commitment mechanism. If you really believe a probability estimate, you should be willing to bet at the relevant odds. Not in real life; in real life you might be risk-avoidant, or the transaction costs might be too high. But in theory you should be willing to bet; thus the saying that “a bet is a tax on bullshit”.

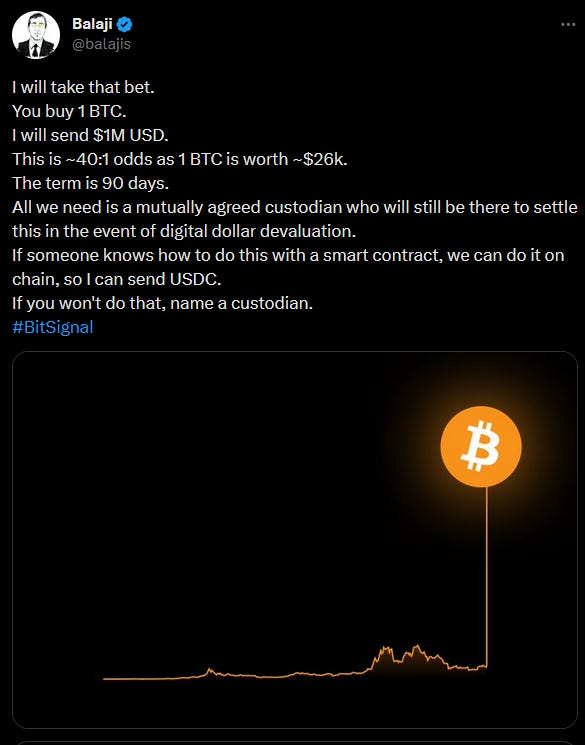

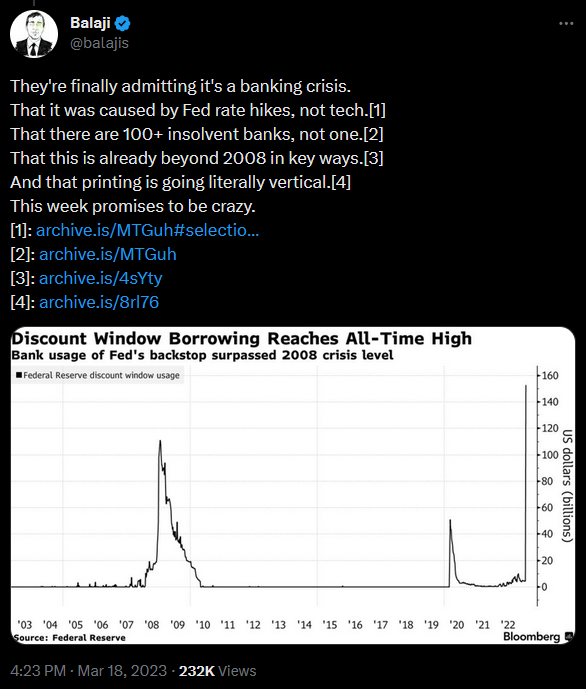

Balaji Srinivasan, a VC, multimillionaire, and Twitter personality, paid his taxes last month. An enthusiastic Bitcoin promoter, he said that the recent run of bank collapses, most notably Silicon Valley Bank, would be the spark for rampant hyperinflation; he urged his followers to switch to Bitcoin immediately.

Another Twitter user, self-described socialist and “tax enthusiast” James Medlock, tweeted:

This was originally meant as a joke; if the US entered hyperinflation, the money would be worthless. But Balaji saw it and took it seriously:

Many people pointed out that this bet was nonsensical from a financial perspective. Even if you believed (like Balaji did) that the US was about to enter hyperinflation and Bitcoin would soon be worth more than $1 million, you could spend the $1 million to buy forty Bitcoins now, which is strictly better than winning one in a bet. Balaji agreed and said he was doing this to raise awareness of coming financial disaster.

(relevant context: Balaji’s estimated net worth is ~$200 million, so this is a non-trivial but still affordable expense for him)

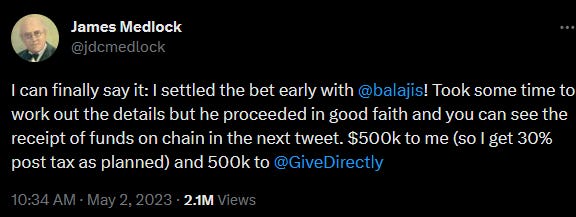

The bet was plagued with difficulties, including difficulty transferring the Bitcoin and $1 million to trusted third parties, plus Matt Levine suggesting it might qualify as illegal Bitcoin market manipulation. As troubles mounted, and with no sign of hyperinflation, Balaji agreed to pay out early, and Medlock confirmed receiving the $1 million, making him the first known case of someone improving their life by posting on Twitter:

Consistent with his oft-stated belief that the rich should be taxed at 70%, Medlock only kept 30% of the $1 million - along with paying the existing taxes, he gave the rest to the charity GiveDirectly.

This is a weird thing to have happen. All of Medlock’s actions make total sense. But what was Balaji thinking?

Cynics speculated that Balaji was trying to pump Bitcoin by fanning hyperinflation panic; if he owned many Bitcoins, he might make a profit above and beyond his million dollar loss. I think this is unlikely; even if he had $100 million in Bitcoin, he would have to increase the price by 1%; I think it’s really hard to raise the price of Bitcoin by 1%. And even if he did this, he would need some way to cash out, either by selling $100 million in Bitcoin or through options or loans; none of these seem like good ideas, and they could all get him in trouble if he was caught (Balaji says he will “never sell BTC for USD”). I think people overestimate the degree to which rich people do things for devious 4D chess reasons, as opposed to the same dumb impulses as all the rest of us (cf. Elon Musk).

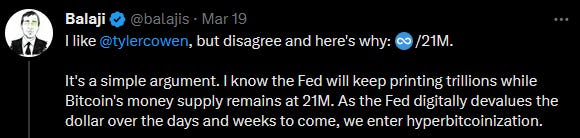

Besides, “what is Balaji thinking?” is a question for which there is always abundant evidence. You can read his blog post, watch his video, or browse his Twitter feed:

He says it was a PR stunt to raise awareness of the Federal Reserve’s bad policy and an impending financial collapse. This seems in keeping with everything else Balaji has ever known/done/believed, so sure. Noah Smith says:

Having known Balaji Srinivasan for more than half of my life, I can attest that he is a man of deeply held beliefs who is bold in his business dealings. Thus, if anyone I know was going to bet some pseudonymous internet rando a million dollars on an outcome that is incredibly unlikely to happen, it would probably be Balaji.

But it’s been almost ninety days, inflation is if anything down, and nothing has collapsed. So was he wrong?

He says no:

Did he actually say this? When I search for these numbers, the earliest reference I can find is this Yahoo article, saying he said it at a conference on April 28, ie the same day he made the tweet. If he believed this while making the bet, I can’t find any reference to it.

And at the time he made the bet, he didn’t really sound like someone trying to communicate that he only thought there was a 10% risk of a near-term crisis:

…and tweets by other people he retweeted without comment:

So who cares?

I care a little because Balaji’s last big prediction was incredible, giving him a reputation for prescience:

And this time around, he pretty strongly appealed to that reputation, retweeting things like:

Bets are a tax on bullshit, and we, too, are “tax enthusiasts” of a sort. But if you’re a multimillionaire, it’s easy for you to pay even very high taxes. At that point, bets’ value lies mostly in their reputational effects. A bet is a public statement of what you believe, operationalized clearly enough that everyone gets to see whether you were right or wrong. Balaji started out with a strong reputation, so a reputational bet was a big deal for him.

But he did a bad job operationalizing it. If he thought hyperinflation was likely in March, he should have said so in so many words, then admitted that his lost bet proved him wrong. If he thought it was only a 10% chance, he should have said so when he was betting (or bet at odds that reflected that) so nobody could accuse him of changing his mind after the fact. As it is, he wants to have his cake (the virtue of being a person who bets on his beliefs) and eat it too (not have to put his positions out there clearly enough for us to tell when they’re wrong).

Still, I appreciate that he’s willing to bet on his beliefs at all; most people don’t even get to that point!

Speaking of which, if the name James Medlock sounds familiar, he previously featured in this column : one of the first big viral markets in Manifold history was him asking whether a stray cat would let him pet her. Now he has $300,000!

There’s a lesson in this. I don’t know what the lesson is, but I am sure it exists.

This Month In Other Markets

Like many of you, I’ve been following the debate around the Google memo - no! not that Google memo! - Google’s OpenAI Has No Moat, And Neither Do We, arguing that open source AI is poised to disrupt its bigcorp competitors. Here are some questions on whether that will happen:

And if you’re following the Book Review contest, here’s a Manifold market on who will win. I notice that Cities got a big boost just after I posted it; I wonder if that will happen consistently or if the number of likes and comments outperformed expectations.