Model City Monday 11/8/21

Telosa, USA

Bloomberg: The Diapers.com Guy Wants To Build A Utopian Megalopolis

Marc Lore founded diapers.com and various other internet startups, served a stint as Wal-Mart’s e-commerce director, and made a few billion dollars. Now he wants to start a city in the deserts of the American West, with a new vision of socially responsible democracy.

Why move to this city instead of one of the many existing cities which are not in deserts and, you know, actually exist? Lore’s pitch is that Telosa (working name) will be inclusive and sustainable by following a Georgist model: all the land will be held in a community-owned trust, and all profits will go to social services.

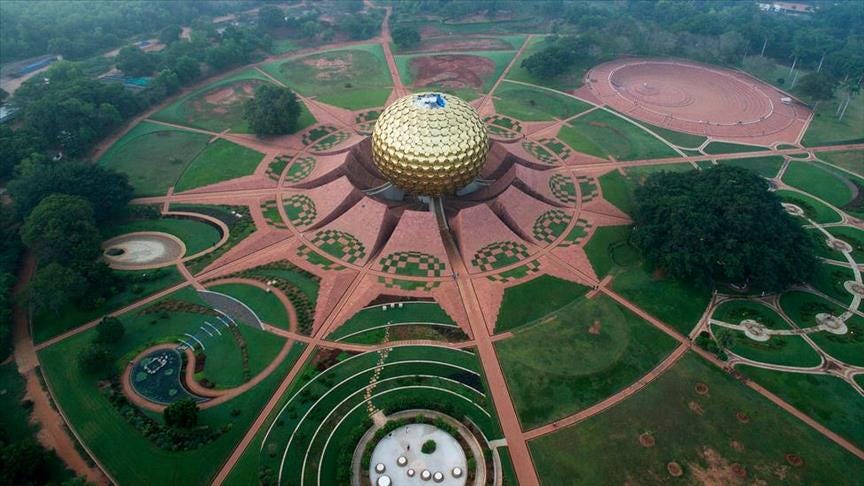

Here’s a picture some artist drew, which we are supposed to believe is relevant in some way.

Here’s a picture some artist drew, which we are supposed to believe is relevant in some way.

I like Georgism as much as anyone else, but I’m not sure a new city in the desert is the right place to try it. Land in the desert is already really cheap. You’d have to really succeed at building a pretty big and desirable city before landlords started capturing a lot of value.

Also, model cities are a weird match for Georgism, because a big part of Georgism is that landowners don’t deserve credit for their land becoming valuable; the land is valuable because it’s in a big desirable city. But in model cities, the landowner (usually the model city founder) is responsible for the city being big and desirable. Usually the founder would keep the land and use the rent to recoup their investment in making the city.

Lore doesn’t seem to want to do that, which is going to be tough. Sure, he has a few billion dollars. But building a city is expensive; he estimates it will cost “over $25 billion for the initial phase (1500 acres, 50,000 residents) and over $400 billion for the city build out.” But, he says, “funding will come from various sources including private investors, philanthropists, federal and state grants, and subsidies for economic development.”

I’m not sure which philanthropists have billions of dollars and want to spend it on a random desert city, or which federal grants have billions of dollars earmarked for random desert cities. Realistically a lot of this is going to depend on the private investors. And private investors tend to want to make a return on their money. If you’ve committed yourself to Georgism, a philosophy specifically designed to make it impossible to get money from increasing land value, you’re making things pretty hard for yourself.

But let’s not think of depressing things like that! Let’s focus on how innovative and diverse and inclusive Telosa is going to be!

There’s a lot of stuff like this. Concerned about education? Telosa will have an innovative diverse inclusive educational system where every student is above average. Concerned about unemployment? Telosa will have lots of innovative diverse inclusive jobs for everybody! How? Usually some bullshit answer like “by fostering a culture of innovative diverse inclusiveness” or something.

I think you can divide these promises into three categories.

First, there’s the stuff that you can potentially solve just by being a well-planned model city. I think sustainable architecture is in this category; people didn’t know it was a thing when they were building New York, but now we do know it, so we can include it. These promises are plausible.

Second, there’s the stuff you get from doing Georgism right. Plausibly having all the profits from the land go into social services means they can afford to have better schools, etc, than anywhere else. I’m skeptical that they can do this, because it trades off against attracting investors, but in theory it’s possible.

Third is the stuff that’s totally made up, and just promises that things will work better in Telosa than elsewhere because they’ll try really hard.

This is especially questionable because I don’t see any claim that Lore or his team will retain any control over the city once it exists; all the documents promise Telosa will be exceptionally democratic. That’s fine, but then why are they making promises to do X or Y? Surely the city government will decide whether they do X and Y or not?

I’m more skeptical of Telosa than some other projects for two reasons. First is that the other projects are libertarian, and libertarianism is easy; if you want to avoid taxes, and you find a jurisdiction that won’t tax you too much, congrats, you’ve achieved your dream. But if you want to build the innovative diverse inclusive city of the future, you have to ask yourself what advantage you have over all the other cities that wish they could do this, but are currently failing (ie all of them). And second, the other projects contain a little bit of an authoritarian element, so that there’s a clear path between the founders wanting something and it being likely to happen - and if there’s any of this in Telosa, they’re hiding it pretty well.

Still, if they can pull this off it would be amazing. Right now we can’t create big cities at will. There’s a lot of demand for big cities (witness all the people moving to NYC and SF despite high prices), but the supply stays capped. It’s a coordination problem: if three million people agreed to create a new big city, a new big city would happen - and they’d be in on the ground floor with land prices. But nobody wants to be the first (or the second, or the 99,999th) person to move to a random uninhabited desert that could potentially become a new metropolis later. Maybe making a lot of big promises like this is what the city creation process looks like. In the end you’d get a new big city, it would probably be more sustainable and walkable than average just because it’s new and well-planned, and even if it wasn’t any more innovative and diverse and inclusive than everywhere else, at least it’s no worse. And all your investors are super rich.

Prospera, Honduras

The latest from Prospera is some kind of drama with the neighboring community of Crawfish Rock over water rights. News site Rest Of World gives local leaders’ version:

In the summer of 2019, after issues with its cistern led Crawfish Rock to lose access to running water, Próspera connected the village to its own water tank. The villagers were grateful. But some villagers were surprised when water bills arrived. Stranger still, monthly payments went to the Institute for Excellence. Why, they wondered, was a charitable foundation acting like a water utility? Brimen would later explain that, in general, Próspera doesn’t “believe in charity as a primary source of support, because I think it creates dependencies.” But dependency, Cárdenas would come to suspect, was exactly what this was all about.

This wasn’t the first time Próspera had insinuated itself into life in Crawfish Rock. In Honduras, patronatos are hyperlocal councils empowered to speak on behalf of their communities. In June 2019, Próspera arranged for villagers to elect a new patronato. Monterroso handpicked a slate of candidates, who ran uncontested.

In May 2020, just after Próspera broke ground, its relationship with Crawfish Rock started to unravel. There were protests over the fact that few construction jobs went to villagers and an outcry after Próspera’s armed security guards, responding to a spate of robberies, began asking people coming and going from Crawfish Rock to identify themselves and state their business. On Próspera’s website, Cárdenas found sketches of its future footprint. Although hard to tell, it looked worryingly like the ZEDE planned to absorb Crawfish Rock, and some villagers worried that Próspera officials would ask the Honduran government to expropriate their land on the ZEDE’s behalf. At best, as Próspera grew, it would cut off Crawfish Rock from the rest of the island, pinning it against the sea.

In June 2020, Brimen, who was stuck in the U.S. due to Covid travel restrictions, sent villagers an almost hour-long voice message over WhatsApp. Próspera would never seek or accept expropriated land, he said. Brimen cataloged all that Próspera’s foundation had done for Crawfish Rock, finally turning to the water supply, for which Próspera had agreed to stop billing during the pandemic. His tone veered from disappointment to veiled threats. “Wow,” he said, in a breathy whisper of faux-astonishment, “how terrible, eh? To live in this modern age and lack running water.” He went on: “Running water to your home, such a basic yet transformative and essential service.” A pause for effect. “Who did that?”

The following month, Brimen flew to Roatán. Several civil society groups had issued a statement criticizing Próspera’s treatment of Crawfish Rock, and he wanted the patronato to disavow it on the village’s behalf. But before that could happen, villagers opposed to the ZEDE called for a new vote, one not orchestrated by Próspera. Though only in her 30s, Cárdenas, now a leader of Crawfish Rock’s opposition to Próspera, was elected vice-president, and her friend Luisa Connor became president.

Throughout early September, Covid-19 cases surged on Roatán. After learning that Brimen planned to hold a public meeting to address community concerns, the new patronato sent him a letter, civil in tone, asking him to postpone the event. “We are open to dialog,” the letter read, “in hopes of a favorable solution, for all parties.” Brimen reacted furiously in a voice message sent to Cárdenas’ mother. He demanded the patronato retract its letter, which he characterized as an assault on free speech and the right to assemble. “They can end up in jail if they keep up this type of behavior,” he said.

Brimen held the meeting that evening in front of the turquoise house in Crawfish Rock — at least until the police shut it down. Cárdenas saw the performance at the public meeting as a PR stunt—the klieg lights, the porch-turned-pulpit. She believes Brimen wanted an incontrovertible record of him engaging with transparency and candor to undermine villagers’ claims that Próspera hadn’t been forthcoming. If so, it backfired. Brimen’s encounter with the police made the rounds on social media and even the local news, only adding to Próspera’s image problem.

In late October, Cárdenas and Connor received an unsigned letter from the Próspera Foundation, a new name for the charitable organization Monterroso oversees. The foundation had heard that the pair were looking at ways of restoring Crawfish Rock’s old water supply. The letter said that the foundation assumed that meant they no longer wanted to access water from the ZEDE’s well, and was going to cut them off in 30 days’ time.

There was only one way to keep the water flowing, the letter concluded — the patronato had to ask for it “in writing on behalf of the community.” A second letter went out at the same time, this one a notice, from Próspera to villagers across Crawfish Rock, alerting them that they would lose water service in 30 days. Próspera placed the blame squarely on the patronato. “The current leaders do not want the community to have access to Próspera-ZEDE sourced water,” the letter claimed, repeating — in a bolded and underlined passage — the ultimatum Cárdenas and Connor had received. If the patronato made a request in writing, the pipes would remain open.

Cárdenas saw it as a divide-and-conquer tactic. The patronato had never asked Próspera to shut off the water, and its members didn’t want the community to go without while they worked to get the old water system online again. But given all that had happened, they refused to sign anything Próspera could spin as proof that the ZEDE had the village’s blessing. A month later, the taps in Crawfish Rock ran dry.

Devon Zuegel, a friend of the blog who was on the ground at Prospera at the time, gives the ZEDE’s version:

Unwanted competition with the water monopoly: The leading family of Crawfish Rock used to be the sole provider of water in the town, and they control the patronato (the town council which claims to speak for the town, sort of like a homeowners’ association). Many people in the village didn’t have access to running water, so Próspera built pipes connecting from the well on their property to the town.

Próspera said that the patronato didn’t like this because it threatened their water monopoly, so they forced Próspera to shut off the water. Several people who live in Crawfish Rock confirmed that “it’s mostly just the patronato that’s opposed to Próspera, the rest of us are positive or neutral”.

I’m probably biased here, but I trust Devon more than I trust some anti-tech e-zine. Other sources confirm that Crawfish Rock citizens have had big problems getting water for a long time. Rest Of World wasn’t really able to deny that Prospera gave Crawfish Rock water when they really needed it, try as they might to make it sound sinister. And they weren’t able to deny that their only condition was that the city officially say they wanted it, which sounds like a pretty reasonable demand with the news coverage being what it is.

Elsewhere In Honduras

Christophe Biocca describes the ZEDE presentations at the Liberty In Our Lifetime conference:

Próspera’s presentation was mostly a rehash of information everyone here knows with a handful of new tidbits. The Apolo Group apartment buildings (totaling 250 units) did break ground recently (they’re still using the La Ceiba, Honduras building code, but not having to deal with zoning and other permitting was a huge draw). The Zaha Hadid residences will break ground “soon”. PES has about 30 people working and living in Próspera and there’s apparently upcoming announcements relating to increasing this massively. They’ve got plans to attract medical and finance (specifically crypto/distributed finance) industries. There’s currently a bank going through the “propose your own regulatory code” process.

Morazán’s presentation was entirely a “what happened since last year” update. They’re making good progress, with 8 houses (more built) and about half of the industrial space they’ve built (2000/4000 m2) rented out. The government entity is already getting close to revenue matching all of the expected expenses (largely off of the tax revenue from the industrial tenant). Massimo (the founder) is considering doing outside fundraising to accelerate construction of phase three one. They also acquired more adjacent land, about 50% of the original site.

In addition, two intentional communities are being built on the other Bay Islands:

Coral Beach Village, sited on Utila, the western neighboring island to Roatán is building an apartment building. The promoter (who runs “Free Talk Live” radio apparently) semi-jokingly mentioned that in the next few years they may ask to join Próspera (or possibly becoming a ZEDE of their own). Guanaja Hills sited on Guanaja, the eastern neighbor, are building bungalows and a dock.

And Greg Foley writes:

Econ Americas interviewed (44-minute video) Guillermo Peña, [Orqueida ZEDE]’s Technical Secretary. He summarizes Honduras’s recent political and economic history (and seems to believe things are getting better). Orchid has 400 employees already and the locals are typically doubling their income. They’ll start exporting in January 2022. They’ll invest $85 million over four years with 2,700 employees eventually. It’s the largest greenhouse in Central America, exporting vegetables and flowers, over 160 hectares. While all three opposition parties are opposed to ZEDEs, Pena is pretty optimistic that the ZEDEs won’t be shut down, at least immediately, if the opposition wins the November election (see 35:25).

Auroville, India

I recently learned about this place, and it’s pretty crazy:

The story is: in the 1910s, a nice Jewish girl moved to India to find herself and fell in with a guru named Sri Aurobindo. Fast forward twenty years and she is calling herself “The Mother” and running what an uncharitable observer might consider maybe sort of kind of a cult.

Fast forward another twenty years and she has a vision of a city built for all humanity. A city where mankind can complete its spiritual transformation into a higher being. A city with a giant gold golf ball in the middle.

(source)

(source)

Thus, Auroville. I don’t know if it’s fair to describe Auroville as a “charter city”, but it does have a charter, which says:

1: Auroville belongs to nobody in particular. Auroville belongs to humanity as a whole. But to live in Auroville, one must be the willing servitor of the Divine Consciousness.

2: Auroville will be the place of an unending education, of constant progress, and a youth that never ages.

3: Auroville wants to be the bridge between the past and the future. Taking advantage of all discoveries from without and from within, Auroville will boldly spring towards future realizations.

4: Auroville will be a site of material and spiritual researches for a living embodiment of an actual human unity.

Auroville was originally planned for 50,000 people, but has about 2,500 official citizens, and about another 10,000 squatters. It seems like an, ahem, highly selected population. From a great Slate article on the town:

Another woman I met from America told me that she’d moved to Auroville because everything in the States “just feels really fake.” She was on the waiting list to become an Aurovilian, a two-year process that requires applicants to prove they are self-sustainable and dedicated to the cause. Applicants are not allowed to leave Auroville for two years and must work for free as a contribution to the township. After two years they face the Entry Services, a small group that reviews applications and ultimately decides who can become an Aurovilian. An Aurovilian from Germany who worked for Entry Services told me her primary job was to weed out what she called “the cuckoos.” I didn’t ask what that meant.

Despite housing the remnants of the Mother’s cult and getting large subsidies from the Indian government (which apparently has some kind of sentimental attachment to it), Auroville currently seems kind of anarchic.

| [](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5bc5b7f2-3144-40e4-8ca8-423283a63aa9_1024x576.jpeg)(source) |

There’s supposed to be some sort of moneyless card-based gift economy, but:

When I arrived I was forced to buy (with cash) an Aurocard, and told to use it in shops and restaurants around the township. It was a bit like a meal card in college: If I lost it, I would have to pay a $10 fine (in cash). But the idea hadn’t quite caught on. The first shop where I tried my Aurocard asked for cash instead. As did the second. When the third asked for cash, I asked why the Aurocard existed. The shopkeeper shrugged uninterestedly.

And the voluntary consensus-based utopian governing structures don’t really seem to work and nobody really knows who is in charge of fixing it. Problems include “robbery, sexual harassment, rape, suicide, and even murder”.

Still, there’s a core population of hippies and seekers who are staying put despite everything. And it’s a great place to be if you want to learn weird kinds of dance, yoga, and faith healing.

Or you could just do what everyone else does and go to the SF Bay Area instead. But after seeing our levels of crime and anarchy maybe you’d rather take your chances with Auroville.

Or you could just do what everyone else does and go to the SF Bay Area instead. But after seeing our levels of crime and anarchy maybe you’d rather take your chances with Auroville.

Honestly the only part of this story which surprises me at all is that the Mother was a Sephardic Jew; usually it’s us Ashkenazi who end up in these kinds of situations.

Elsewhere In Model Cities

— An attempt to turn a cruise ship into a cryptocurrency-themed seastead has failed.

— The Charter Cities Institute has created a Governance Handbook. If you just remembered that you have to govern a charter city tomorrow and forgot to study, this is your cram sheet.

— Did you know: in 2018, the Nebraska Assembly came within one vote of creating a charter city which would have been “sovereign…not subject to Nebraska laws or regulations”