More Antifragile, Diversity Libertarianism, And Corporate Censorship

In yesterday’s review of Antifragile , I tried to stick to something close to Taleb’s own words. But here’s how I eventually found myself understanding an important kind of antifragility.

I feel bad about this, because Taleb hates bell curves and tells people to stop using them as examples, but sorry, this is what I’ve got.

I feel bad about this, because Taleb hates bell curves and tells people to stop using them as examples, but sorry, this is what I’ve got.

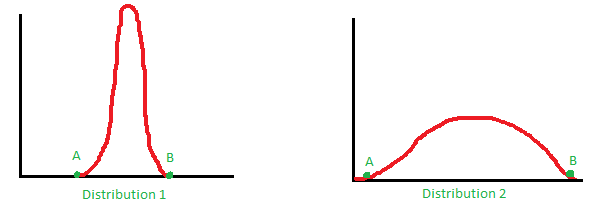

Suppose that Distribution 1 represents nuclear plants. It has low variance, so all the plants are pretty similar. Plant A is slightly older and less fancy than Plant B, but it still works about the same.

Now we move to Distribution 2. It has high variance. Plant B is the best nuclear plant in the world. It uses revolutionary new technology to squeeze extra power out of each gram of uranium, its staff are carefully-trained experts, and it’s won Power Plant Magazine’s Reactor Of The Year award five times in a row.

Plant A suffers a meltdown after two days, killing everybody.

If you live in a region with lots of nuclear plants, you’d prefer they be on the first distribution, the low-variance one. Having some great nuclear plants is nice, but having any terrible ones means catastrophe. Much better for all nuclear plants to be mediocre.

Okay, now suppose that Distribution 1 represents car companies in your region. Again, it has low variance, so they’re all pretty similar. Ford vs. GM, something like that.

What about Distribution 2? Now Point B is Tesla, making revolutionary new environmentally-friendly cars. In fact, let’s say it’s some super-Tesla that’s even better than the real Tesla, plus their cars are affordable even for the poorest people. Point A is Yugo (or if you know a more modern example of a terrible car company, use that). Now which distribution would you rather have?

Distribution 2, definitely! You can buy the super-Tesla and be very happy, without ever worrying about Yugo. In fact, after a few years Yugo will go out of business, super-Tesla will dominate the market, and everyone will be very happy.

Your only regret is that you can’t move to a Distribution 3 where the variance is even higher. On Distribution 3, Company A’s cars literally can’t move, or back up when you try to move them forward, or immediately catch fire. Company B produces flying cars that cost $100 and suck carbon out of the air wherever they go, plus their emissions cure cancer. Nobody ever purchases a car from Company A, Company B captures the market and spawns equally impressive competitors, it’s win-win. Your only regret is that there’s no Distribution 4 where the variance is even higher…

So: nuclear plants are fragile. You want them to have as little variance as possible. Car companies are antifragile. You want them to have as much variance as possible.

Or more generally: in an area with frequent catastrophes, where the catastrophes have externalities on people who didn’t choose them, you want to lower variance, so that nothing ever gets bad enough to produce the catastrophe.

In an area where people can choose whatever they want, and are smart enough to choose good things rather than bad ones, you want to raise variance, so that the best thing will be very good indeed, and then everybody can choose that and bask in its goodness.

That second point is a bog-standard libertarian argument. You want there to be as many things as possible, as different from each other as possible, so that there can be at least one that’s good. You can apply the argument to freedom of speech (you want to hear as many opinions as possible to maximize your chance of hearing the true one), charter cities (you want as many different political regimes as possible so you can figure out which one maximizes human flourishing, and then you either move to that one, or take advantage of the scientific and economic goods it produces), charter schools (you want as many different kinds of school as possible, so you can find out which one educates kids best and go there), et cetera.

But maybe it’s not bog-standard enough. People tend to get surprised whenever libertarians differ from the most strawmannish version of Ayn Rand. But I find my disagreements with her map pretty closely to this idea of “diversity libertarianism”. I’m less likely to object to things like taxing the rich, redistributing wealth, or removing externalities on carbon - none of those decrease diversity very much. And I’m more likely to care about conformist pressures from religions or mobs, even though technically those don’t involve government.

Earlier this year, Amazon, Apple, and Google simultaneously decided to block access to Parler on their app stores. A lot of libertarians objected that it was pretty scary that corporations have so much power to restrict speech they don’t like, and a lot of anti-libertarians made fun of them: this is just corporations making their own decisions about their corporate property! Isn’t that what you libertarians want?

I think diversity libertarianism offers a reason why it isn’t.

Diversity libertarianism is usually in favor of companies being allowed to do a wide range of things, because it ensures everyone will be well-served. If you assume an arbitrarily large number of uncorrelated companies, then whatever the thing you want is, there’s at least one existing or easy-to-start company doing it. If Ford refuses to sell cars to black people, Toyota should see a profit opportunity and step in. If both Ford and Toyota ban blacks at the same time, some upstart like Tesla should step in. If Ford, Toyota, and Tesla all do it, some guy with a wrench who’s always dreamed of making cars in his garage should notice a billion-dollar business opportunity lying on the ground, get seed capital from equally greedy investors, and solve the problem.

When might this not work? First, if cars are hard, and starting a new car company takes too much time. I’m not too concerned about this one. I think a lot of people could potentially make one or two crappy 1920s-style cars in their garage with a little work, and once they do that, black people with no other options will buy them, and that will give them enough money to bootstrap into a powerful car company that can compete with the big dogs. Tesla did something like this when Musk though the big dogs were neglecting electric, and that went great.

But other fields have higher entry barriers than cars do. Apple and Google both blocked Parler from their phones. But these are the only two major smartphone companies. It would probably take at least a decade to set up another one, and although I think there’s some demand, I’m not sure that demand can coordinate itself into a phone company that doesn’t do this kind of thing.

And more important than these kinds of theoretical objections - in the real world there were times and places where all companies refused good service to blacks for several hundred years. Economists have shown that this wasn’t exactly organic - companies were afraid to give blacks good jobs, to pay them higher wages, or to sell them products they weren’t supposed to have; they figured racist mobs would attack them, racist employees would desert them, or a racist government would crack down on them.

I tend to think of this as a religious problem, by analogy to very religious towns where eg nobody will sell liquor even though there’s no official law against it, or fundamentalist areas where it’s impossible to admit you’re an atheist even though there are no laws against it. In some times and places, racism took on an almost-religious level of fervour, and that was enough to soft-“regulate” companies into compliance even when governments didn’t officially weigh in on the issue. Having lots of companies only works when they’re uncorrelated, and religions ensure correlations approaching 1 on the issues they care about.

Right now there’s religious pressure on tech companies to conform. Someone on Twitter pointed out that tech censoring Parler isn’t a sign of their strength, but of their weakness. Imagine that Mark Zuckerberg decided he personally really disliked BLM, and he was going to censor BLM and any people/organizations/apps that promoted it from Facebook. Do you think he would succeed? Do you think he could stay CEO of Facebook after he was found to be doing this? Mark Zuckerberg and Big Tech in general are as much slaves to the prevailing religion as the rest of us; their “power” is the power to choose between medium vs. high levels of conformity.

If you’re an anti-government libertarian, I’m not sure there’s much you can do besides shrug and say that religion isn’t government, so this kind of thing is fine. In fact, I think some paleolibertarians think of this as a feature rather than a bug; they want government out of the way so (their) religion can rule the roost. But if you’re a diversity libertarian, you’re worried that religions can decrease variance of options the same way governments can. The evangelical Christian town where nobody will tolerate gay people may not have laws against homosexuality, but gay people still won’t be able to find a church, community, or business that meets their needs.

I’m not going to argue the merits of constraining vs. not constraining Big Tech here, except to say that I usually err on the side of regulation not being the answer. My point is that it’s not hypocritical for libertarians to support a wide variety of corporations with different policies, and also oppose coordinated corporate censorship.

(If you did want to argue against diversity libertarianism, you’d want to show that relevant systems are more fragile than anti-fragile; giving people more options will usually make them worse. Maybe the slightest failure could cause catastrophe - I think free speech opponents think this is true, but I’m less sure they’re right. Or people will perversely choose the worst option rather than the best if many options are made available - I think this is sometimes true for things like drugs and gambling. or there are overwhelming externalities. Or there are externalities, which can range from the very simple like pollution to the very complicated, like whether your working for a low wage has externalities because it forces me to compete with you. I think figuring out where to draw the lines here is really hard - but if you want to convince me, this would be more fruitful than the umpteenth essay about how the First Amendment only applies to government)

Even beyond politics, I think this predicts a sort of ethos of what I like and what I don’t like. The quickest way to enrage me is to criticize some group of weird people doing their own thing without harming anyone - to try to browbeat them into doing the same thing as everyone else. That group might be just a tiny bit of slack away from creating something amazing!