My Left Kidney

A person has two kidneys; one advises him to do good and one advises him to do evil. And it stands to reason that the one advising him to do good is to his right and the one that advises him to do evil is to his left.

— Talmud (Berakhot 61a)

I.

As I left the Uber, I saw with horror the growing wet spot around my crotch. “It’s not urine!”, I almost blurted to the driver, before considering that 1) this would just call attention to it and 2) it was urine. “It’s not my urine,” was my brain’s next proposal - but no, that was also false. “It is urine, and it is mine, but just because it’s pooling around my crotch doesn’t mean I peed myself; that’s just a coincidence!” That one would have been true, but by the time I thought of it he had driven away.

Like most such situations, it began with a Vox article.

II.

I make fun of Vox journalists a lot, but I want to give them credit where credit is due: they contain valuable organs, which can be harvested and given to others.

I thought about this when reading Dylan Matthews’ Why I Gave My Kidney To A Stranger - And Why You Should Consider Doing It Too. Six years ago, Matthews donated a kidney. Not to any particular friend or family member. He just thought about it, realized he had two kidneys, realized there were thousands of people dying from kidney disease, and felt like he should help. He contacted his local hospital, who found a suitable recipient and performed the surgery. He described it as “the most rewarding experience of my life”:

As I’m no doubt the first person to notice, being an adult is hard. You are consistently faced with choices — about your career, about your friendships, about your romantic life, about your family — that have deep moral consequences, and even when you try the best you can, you’re going to get a lot of those choices wrong. And you more often than not won’t know if you got them wrong or right. Maybe you should’ve picked another job, where you could do more good. Maybe you should’ve gone to grad school. Maybe you shouldn’t have moved to a new city.

So I was selfishly, deeply gratified to have made at least one choice in my life that I know beyond a shadow of a doubt was the right one.

Something about that last line struck a chord in me. Still, making decisions about internal organs based on a Vox article sounded like the worst idea. This was going to require more research.

III.

Matthews says kidney donation is fantastically low-risk:

The risk of death in surgery is 3.1 in 10,000, or 1.3 in 10,000 if (like me) you don’t suffer from hypertension. For comparison, that’s a little higher and a little lower, respectively, than the risk of pregnancy-related death in the US1. The risk isn’t zero (this is still major surgery), but death is extraordinarily rare. Indeed, there’s no good evidence that donating reduces your life expectancy at all […]

The procedure does increase your risk of kidney failure — but the average donor still has only a 1 to 2 percent chance of that happening. The vast majority of donors, 98 to 99 percent, don’t have kidney failure later on. And those who do get bumped up to the top of the waiting list due to their donation.

I checked the same resources Matthews probably had, and I agreed.

It was my girlfriend (at the time) who figured out the flaw in our calculation. She was both brilliant and pathologically anxious, which can be a powerful combination: her zeal to justify her neuroses gave her above-genius-level ability to ferret out medical risks that doctors and journalists had missed. She made it her project to dissuade me from donating, did a few hours’ research, and reported back that although the risk of dying from the surgery was indeed 1/10,000, the risk of dying from the screening exam was 1/660 .

I regret to inform you she may be right. The screening exam involves a “multiphase abdominal CT”, a CAT scan that looks at the kidneys and their associated blood vessels and checks if they’re all in the right place. This involves a radiation dose of about 30 milli-Sieverts. The usual rule of thumb is that one extra Sievert = 5% higher risk of dying from cancer, so a 30 mS dose increases death risk about one part in 660. There are about two nonfatal cases of cancer for every fatal case, so the total cancer risk from the exam could be as high as 1/2202. I’m not a radiologist, maybe I’m totally wrong here, but the numbers seemed to check out.

I discussed this concern with transplant doctors at UCSF and the National Kidney Foundation, who seemed very surprised to hear it, but couldn’t really come up with any evidence against. I asked if they could do the kidney scan with an MRI (non-radioactive) instead of a CT. They agreed3.

The short-term risks taken care of, my girlfriend and I moved on to arguing about the longer-term ones. One kidney starts out with half the GFR (glomerular filtration rate, a measure of the kidneys’ filtering ability) of two kidneys. After a few months, it grows a little to pick up the slack, stabilizing at about 70% of your pre-donation GFR. 70% of a normal healthy person’s GFR is more than enough.

But you lose GFR as you age. Most people never lose enough GFR to matter; they die of something else first. But some people lose GFR faster than normal and end up with chronic kidney disease, which can cause fatigue and increase your chance of other problems like heart attacks and strokes. If you donate one kidney, and so start with only 70% of normal GFR, you have a slightly higher chance of being in this group whose GFR decline eventually becomes a problem. How much of a chance? According to Matthews, “1 to 2 percent”.

The studies showing this are a bit of a mess. Non-controlled studies find that kidney donors have lower lifetime risk of kidney disease than the general population. But this is because kidney donors are screened for good kidney health. It’s good to know that donation is so low-risk that it doesn’t overcome this pre-existing advantage. But in order to quantify the risk exactly, we need to find a better control group.

Two large studies tried to compare kidney donors to other people who would have passed the kidney donation screening if they had applied, and who therefore were valid controls. An American study of 347 donors found no increased mortality after an average followup of 6 years. A much bigger and better Norwegian study of 1901 donors found there was increased mortality after 25 years - so much so that the donors had an extra 5% chance of dying during that period (ie absolute risk increase). But looking more closely at the increased deaths, they were mostly from autoimmune diseases that couldn’t plausibly be related to their donations. The researchers realized that most kidney donors give to family members. If your family member needs a kidney donation, it probably means they have some disease that harms the kidneys. Lots of diseases are genetic, so if your family members have them, you might have them too. They suspected that the increase in mortality was mostly because of genetic diseases which these donors shared with their kidney-needing relatives - diseases which may not have shown up during the screening process.

Muzaale et al investigate this possibility in a sample of 96,217 donors. They were only able to follow for an average 7 years, but used curves derived from other samples to project up to 15 years. They found 34 extra cases of ESRD (end-stage renal disease, the most severe form of kidney disease) per 10,000 donors who were related to their recipients, compared to 15 cases per 10,000 for donors who weren’t (the difference wasn’t statistically significant, but I think it’s still correct for unrelated donors to use the unrelated donor number). They estimated a total increased risk of 78/10,000 per lifetime; although I can’t prove it, I think by analogy to the earlier statistic this number should plausibly be ~halved for unrelated donors. So I think that if anything, Matthews is overestimating how worried to be - the real number could be as low as an 0.5 - 1% increase.

On the other hand, I discussed this with my uncle, a nephrologist (kidney doctor), who says he sees suspiciously many patients who donated kidneys 30+ years ago and now have serious kidney disease. None of these studies have followed subjects for 30+ years, and although they can statistically extend their projections, something weird might happen after many decades that deviates from what you would get by just extrapolating the earlier trend. I was eventually able to find Ibrahim et al, which follows some kidney donors for as long as 30-40 years. They find no negative deviation from trend after the 20 year mark. Even up to 35-40 years, donors continue to have less kidney disease than the average non-donor.

This isn’t controlling for selection bias - but neither was my uncle’s anecdotal observation. So although it does make me slightly nervous, I’m not going to treat it as actionable evidence.

Still, my girlfriend ending up begging me not to donate, and I caved. But we broke up in 2019. The next few years were bumpy, but by 2022 my life was in a more stable place and I started thinking about kidneys again. By then I was married. I discussed the risks with my wife and she decided to let me go ahead. So in early November 2022, for the second time, I sent a form to the University of California San Francisco Medical Center saying I wanted to donate a kidney.

IV.

Something else happened that month. On November 11, FTX fell apart and was revealed as a giant scam. Suddenly everyone hated effective altruists. Publications that had been feting us a few months before pivoted to saying they knew we were evil all along. I practiced rehearsing the words “I have never donated to charity, and if I did, I certainly wouldn’t care whether it was effective or not”.

But during the flurry of intakes, screenings, and evaluations that UCSF gave me that month, the doctors asked “so what made you want to donate?” And I hadn’t rehearsed an answer to this one, so I blurted out “Have you heard of effective altruism?” I expected the worst. But the usual response was “Oh! Those people! Great, no further explanation needed.” When everyone else abandoned us, the organ banks still thought of us as those nice people who were always giving them free kidneys.

We were giving them a lot of free kidneys. When I talked to my family and non-EA friends about wanting to donate, the usual reaction was “You want to what?!” and then trying to convince me this was unfair to my wife or my potential future children or whatever. When I talked to my EA friends, the reaction was at least “Cool!”. But pretty often it was “Oh yeah, I donated two years ago, want to see my scar?” Most people don’t do interesting things unless they’re in a community where those things have been normalized. I was blessed with a community where this was so normal that I could read a Vox article about it and not vomit it back out.

This is surprising, because kidney donation is only medium effective, as far as altruisms go4. The average donation buys the recipient about 5 - 7 extra years of life (beyond the counterfactual of dialysis). It also improves quality of life from about 70% of the healthy average to about 90%. Non-directed kidney donations can also help the organ bank solve allocation problems around matching donors and recipients of different blood types. Most sources say that an average donated kidney creates a “chain” of about five other donations, but most of these other donations would have happened anyway; the value over counterfactual is about 0.5 to 1 extra transplant completed before the intended recipient dies from waiting too long. So in total, a donation produces about 10 - 20 extra quality-adjusted life years.

This is great - my grandfather died of kidney disease, and 10 - 20 more years with him would have meant a lot. But it only costs about $5,000 - $10,000 to produce this many QALYs through bog-standard effective altruist interventions, like buying mosquito nets for malarial regions in Africa. In a Philosophy 101 Thought Experiment sense, if you’re going to miss a lot of work recovering from your surgery, you might as well skip the surgery, do the work, and donate the extra money to Against Malaria Foundation instead5.

Obviously this kind of thing is why everyone hates effective altruists. People got so mad at some British EAs who used donor money to “buy a castle”. I read the Brits’ arguments: they’d been running lots of conferences with policy-makers, researchers, etc; those conferences have gone really well and produced some of the systemic change everyone keeps wanting. But conference venues kept ripping them off, having a nice venue of their own would be cheaper in the long run, and after looking at many options, the “castle” was the cheapest. Their math checked out, and I believe them when they say this was the most effective use for that money. For their work, they got a million sneering thinkpieces on how “EA just takes people’s money to buy castles, then sit in them wearing crowns and waving scepters and laughing at poor people”. I respect the British organizers’ willingness to sacrifice their reputation on the altar of doing what was actually good instead of just good-looking.

I worry that people use suffering as a heuristic for goodness. Mother Teresa becomes a hero because living with lepers in the Calcutta slums sounds horrible - so anyone who does it must be really charitable (regardless of whether or not the lepers get helped). Owning a castle is the opposite of suffering - it sounds great - therefore it is fake charity (no matter how much good you do with the castle).

This heuristic isn’t terrible. If you’re suffering for your charity, then it must seem important to you, and you’re obviously not doing it for personal gain. If you do charity in a way that benefits you (like gets you a castle), then the personal gain aspect starts looking suspicious. The problem is the people who elevate it from a suspicion to an automatic condemnation. It seems like such a natural thing to do. And it encourages people to be masochists, sacrificing themselves pointlessly in photogenic ways, instead of thinking about what will actually help others.

But getting back to the point: kidney donation has an unusually high ratio of photogenic suffering to altruistic gains. So why do EAs keep doing it? I can’t speak for anyone else, but I’ll speak for myself.

It starts with wanting, just once, do a good thing that will make people like you more instead of less. It would be morally fraught to do this with money, since any money you spent on improving your self-image would be denied to the people in malarial regions of Africa who need it the most. But it’s not like there’s anything else you can do with that spare kidney.

Still, it’s not just about that. All of this calculating and funging takes a psychic toll. Your brain uses the same emotional heuristics as everyone else’s. No matter how contrarian you pretend to be, deep down it’s hard to make your emotions track what you know is right and not what the rest of the world is telling you. The last Guardian opinion columnist who must be defeated is the Guardian opinion columnist inside your own heart. You want to do just one good thing that you’ll feel unreservedly good about, and where you know somebody’s going to be directly happy at the end of it in a way that doesn’t depend on a giant rickety tower of assumptions.

Dylan Matthews wrote:

As I’m no doubt the first person to notice, being an adult is hard. You are consistently faced with choices — about your career, about your friendships, about your romantic life, about your family — that have deep moral consequences, and even when you try the best you can, you’re going to get a lot of those choices wrong. And you more often than not won’t know if you got them wrong or right. Maybe you should’ve picked another job, where you could do more good. Maybe you should’ve gone to grad school. Maybe you shouldn’t have moved to a new city.

So I was selfishly, deeply gratified to have made at least one choice in my life that I know beyond a shadow of a doubt was the right one.

…and it really resonated. Everything else I try to do, there’s a little voice inside of me which says “Maybe the haters are right, maybe you’re stupid, maybe you’re just doing the easy things. Maybe you’re no good after all, maybe you’ll never be able to figure any of this out. Maybe you should just give up.”

The Talmud is very clear: that voice is called the evil inclination, and it dwells in the left kidney. There is only one way to shut it off forever. I was ready.

V.

You might not be a masochist. But hospitals are sadists. They want to hear you beg.

After I submitted the donation form, I was evaluated by a horde of indistinguishable women. They all had titles like “Transplant Coordinator”, “Financial Coordinator”, and “Patient Care Representative”. Several were social workers; one was a psychiatrist. They would see me through a buggy version of Zoom that caused various parts of their body to suddenly turn into the UCSF logo, and they all had questions like “Are you sure you want to do this?” and “Are you going to regret this later?” and “Is anyone pressuring you to do this?” and “Are you sure you want to do this?”

After clearing that gauntlet came the tests. Blood tests - I think I must have given between 20 and 50 vials of blood throughout the screening process. Urine tests - both the normal kind where you pee in a cup, and a more involved kind where you have to store all your urine for 24 hours in a big jug, then take it to the lab. “Urinate into a jug” ought to be the easiest thing in the world, but some of the labs have overly complicated jugs that I, with my mere MD, couldn’t always get right - hence my experience accidentally pouring urine on myself in an Uber.

Then came the big guns. Echocardiogram. MRI. One of my urine tests was slightly off, so I also got a nuclear kidney scan, where they injected radioactive liquid in me and monitored how long it took to come out the other end (I remember asking a friend “Can I use your bathroom? My urine might be slightly radioactive today, but it shouldn’t be enough to matter.”)

Finally, five months after I originally applied, I got a phone call from the Transplant Coordinator. The test results were in, and . . . I had been rejected because I’d had mild childhood OCD.

This was something I’d mentioned offhandedly during one of the psych evaluations. As a child, I used to touch objects in odd patterns that only made sense to me. I got diagnosed with OCD, put on SSRIs for a while, finally did therapy at age 15, hadn’t had any problems since. I still go back on SSRIs sometimes when I’m really stressed, and will grudgingly admit to the occasional odd-pattern-touching when no one’s looking.

But it’s nothing anyone would know about if I didn’t tell them! It was mild even at age 15, and it’s been close-to-nonexistent for the past twenty years! Now I’m a successful psychiatrist who owns his own psychiatry practice and helps other people with the condition! I told them all this. They didn’t care.

I asked them if there was anything I could do. They said maybe I could go to therapy for six months, then apply again.

I asked them what kind of therapy was indicated for mild OCD that’s been in remission for twenty years. They sounded kind of surprised to learn there were different types of therapy and said whatever, just talk to someone or something.

I asked them how frequent they thought the therapy needed to be. They sounded kind of surprised to learn that therapy could have different frequencies, and said, you know, therapy , the thing where you talk to someone.

I asked them if they actually knew anything about OCD, psychotherapy, or mental health in general, or if they had just vaguely heard rumors that some people were bad and crazy and shouldn’t be allowed to make their own decisions, and that a ritual called “therapy” could absolve one of this impurity. They responded as politely as possible under the circumstances, but didn’t change their mind.

I wasn’t going to waste an hour a week for six months, and spend thousands of dollars of my own extremely-not-reimbursed-by-UCSF money, to see a randomly-selected therapist for a condition I’d gotten over twenty years ago, just so I could apply again and get rejected a second time.

This was one of the most infuriating and humiliating things that’s ever happened to me. We throw around a lot of terms like “stigma” and “paternalism”, and I’ve worked with patients who have dealt with all these issues (it’s UCSF in particular a surprising amount of the time!). But I was still surprised how much it hurt when it happened to me. Being denied the right to control your own body because of some meaningless diagnosis on a chart somewhere is surprisingly frustrating, even compared to things that should objectively be worse. I thought I was going to be able to do a good deed that I’d been fantasizing about for years, and some jerk administrator torpedoed my dreams because I had once, long ago, had mild mental health issues.

So I gave up.

I spent the next few weeks unleashing torrents of anti-UCSF abuse at anyone who would listen. This turned out to be very productive! When I was unleashing a torrent of anti-UCSF abuse to Josh Morrison of WaitlistZero, he asked if I’d tried other hospitals.

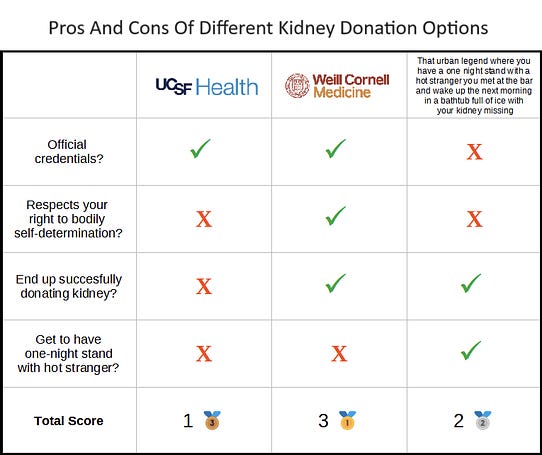

I hadn’t. I’d assumed they were all in cahoots. But Josh said no, each hospital had their own evaluation process. Weill Cornell, a hospital in NYC, was one of the best transplant centers in the country, and had a reputation for fair and thoughtful pre-donor screening. Why didn’t I talk to them?

NYC was far away, and I hate to travel, but I was just angry enough to accept. At this point I’d forgotten whatever good altruistic motivations I might have originally had and was fueled entirely by spite. Getting my kidney taken out somewhere else felt like it would be a sort of victory over UCSF. So I went for it.

Cornell was lovely. They tried to do as much of the process as they could via Californian intermediaries, so that I only had to fly to New York twice. Their psychiatrist evaluated me, listened to me explain my weak history of OCD, then treated me like a reasonable adult who tells the truth and can handle his own medical decisions. They were concerned that I sometimes self-prescribed Lexapro to deal with anxiety. But we agreed on a compromise: I found another psychiatrist, let her give me the exact same prescription of Lexapro at a much higher cost to my insurance, and that resolved the problem.

So in late September 2023 - ten months after I started the process - I finally got fully cleared to donate, surgery set for October 12.

VI.

I knew, in theory, that anaesthetics existed. Still, it’s weird. One moment you’re lying on a table in the OR, steeling yourself up for one of the big ordeals of your life. The next, you’re in a bed in the recovery room, feeling fine. The operation - this thing you’ve been thinking about and dreading for months - exists only as a lacuna in your memory. Not even some kind of fancy lacuna, where you remember the darkness closing in on you beforehand, or have to claw yourself back into consciousness afterwards. The most ordinary of lacunas, like a good night sleep.

There was no pain, not at first. The painkillers and nerve blocks lasted about a day after the surgery. By the time they wore off, it was more of a dull ache. The hospital offered me Tylenol, and I wanted to protest - really? Tylenol? After major surgery? But the Tylenol worked.

Some people will have small complications (I am a doctor, pretty jaded, and my definition of “small” may be different from yours). Dylan Matthews wrote about an issue where his scrotum briefly inflated like a balloon (probably this is one of the ones that doesn’t feel small when it’s happening to you). I missed out on that particular pleasure, but got others in exchange. I had an unusually hard time with the catheter - the nurse taking it out frowned and said the team that put it in had “gone too deep”, as if my urinary tract was the f@#king Mines of Moria - but that was fifteen seconds of intense pain. Then a week afterwards, just when I thought I’d recovered fully, I got bowled over by a UTI which knocked me out for a few days. But overall, I was surprised by the speed and ease of my recovery.

A few hours after the surgery, I walked a few steps. After a day, I got the catheter out and could urinate normally again. After two days, I was eating “SmartGel”, a food substitute that has mysteriously failed to catch on outside of the immobilized-hospital-patient market. After three, I was out of the hospital. After four, I started easing myself back into (remote) work. After a week, I flew cross-country.

. . . and then I got the UTI. If this section sounds schizophrenic, it’s because it’s a compromise between an original draft where I said nothing went wrong and it was amazing, and a later draft written after a haze of bladder pain. Just don’t develop complications, that’s my advice.

Still, I recently heard from the surgeon that my recipient’s side of the surgery was a success, that my kidney was in them and going fine - and that put things back into perspective. To a first approximation , compared to the inherent gravity of taking an organ out of one person and putting it in a second person and saving their life - it was all easy and everything went well. When I look back on this in a decade, I’ll remember it as everything being easy and going well. Even now, with some lingering bladder pain, modern medicine still feels like a miracle.

VII.

In polls, 25 - 50% of Americans say they would donate a kidney to a stranger in need.

This sentence fascinates me because of the hanging “would”. Would , if what? A natural reading is “would if someone needs it”. But there are 100,000 strangers on the waiting list for kidney transplants. Between 5,000 and 40,000 people die each year for lack of sufficient kidneys to transplant. Someone definitely needs it. Yet only about 200 people (0.0001%) donate kidneys to strangers per year. Why the gap between 25-50% and 0.0001%?

Some of you will suspect respondents are lying to look good. But these are anonymous surveys. Lying to themselves to feel good, then? Maybe. But I think about myself at age 20, a young philosophy major studying utilitarianism. If someone had asked me a hypothetical about whether I would donate a kidney to a stranger in need, I probably would have said yes. Then I would have continued going about my business, never thinking of it as a thing real-life people could do. Part of this would have been logistics. I wouldn’t have known where to start. Do you need to have special contacts in the surgery industry? Seek out a would-be recipient on your own? Where would you find them? But more of it would have been psychological: it just wasn’t something that the people I knew did, and it would be weird and alienating for me to be the only one.

This is going to be the preachy “and you should donate too!” section you were dreading all along, but I’m not going to make a lot of positive arguments. If 90% of the people who answer yes on those surveys are lying to feel good, then only 3 - 5% really want to donate. But bringing the donation rate from 0.0001% of people to 3 - 5% of people would solve the kidney shortage many times over. The point isn’t to drag anti-donation-extremists kicking and screaming to the operating table. The point is to reach the people who already want to do it, and make them feel comfortable starting the process.

20-year-old me was in that category. The process of making him feel comfortable involved fifteen years of meeting people who already done it. During residency, I met a fellow student doctor who had donated. Later, I got involved in effective altruism, and learned that movement leader Alexander Berger - a guy who can easily direct millions of dollars at whatever cause he wants - had donated his personal kidney as well. Some online friends. Some people I met at conferences. And Dylan Matthews, who I kept crossing paths with (most recently at the Manifest journalism panel). After enough of these people, it no longer felt like something that nobody does, and then I felt like I had psychological permission to do it.

(obviously saints can do good things without needing psychological permission first, but not everyone has to be in that category, and I found it easier to get the psychological permission than to self-modify into a saint6.)

So I’m mostly not going to argue besides saying: this is a thing I did, it’s a thing hundreds of other people do each year, getting started is as simple as filling out a form , and if it works for you, you should go for it7.

When I woke up in the recovery room after surgery, I felt great. Amazing. Content, peaceful, proud of myself. Mostly this was because I was on enough opioids to supply a San Francisco homeless encampment for a month. But probably some of it was also the warm glow of having made a difference or something. That could be you!

VIII.

The ten of you who will listen to this and donate are great. That brings the kidney shortage down from 40,000 to 39,990/year.

Everyone knows we need a systemic solution, and everyone knows what that solution will eventually have to be: financial compensation for kidney donors. But so far they haven’t been able to get together enough of a coalition to overcome the usual cabal of evil bioethicists who thwart every medical advance.

My kidney donation “mentor”8 Ned Brooks is starting a new push - the Coalition To Modify NOTA - which proposes a $100,000 refundable tax credit - $10,000 per year for 10 years - for kidney donors. There would be a waiting period and you’d have to get evaluated first, so junkies couldn’t walk in off the street and get $100K to spend on fentanyl. No intermediate company would “profit” off the transaction, and rich people wouldn’t be able to pay directly to jump in line. It would be the same kidney donation system we have now, except the donors get $100,000 back after saving the government $1MM+.

(the libertarian in me would normally prefer a free market, but “avoid taxes by selling your organs” also has a certain libertarian appeal)

This came up often when I talked to other donors. They all had various motivations, but one of the things they cared about was being able to advocate for these kinds of systemic changes more effectively. I personally have been wanting to push this in an essay here for a while, but it seemed hypocritical to play up the desperate kidney shortage while I still had two kidneys. Now I can support NOTA modification whole-heartedly . . . full-throatedly? . . . it’s weird how many of these adverbs involve claims to still have all of your organs.

This is also one of the answers to the question I asked in section IV: how do you balance acts of heroic altruism that everyone will love you for vs. acts of boring autistic altruism that will make everyone hate you, but which will accomplish more good in the end?) Coalition To Modify NOTA is full of previous living kidney donors, who are using the moral clout and recognition they’ve gotten to get attention and change the system in an unglamorous way. I find this an admirable way of squaring the circle: do the flashy heroic things to gain social capital, then spend the social capital on whatever’s ultimately most important.

If you get one takeaway from this, let it be that those guys who bought the castle were good guys. Two takeaways, and it’s that plus modify NOTA. Three takeaways, and you should feel permission to (if you want) donate a kidney. You can sign up here.9 Feel free to email me at scott@slatestarcodex.com if you have questions about the process.

-

You shouldn’t have to pay much money. If, like me, you need to travel (eg to New York), kidney related charities will reimburse your travel costs (in theory, I haven’t yet proven this, and a few costs were illegible and I decided not to submit them).

-

You shouldn’t have to lose too much money from work. Kidney-related charities will pay for lost wages during recovery, again read the small print before trusting this 100%.

-

You don’t need to worry about not having a kidney when a friend or family member needs one. When you donate, you can give the organ bank the names of up to five friends or family members who you’re worried might end up in this situation. In exchange for your donation, they will make sure those people get to the top of the list if they ever need a transplant themselves.

-

95% of donors say if they could do it all over, they would donate again. My impression is the most common reasons people wouldn’t is because they donated to a family member and it made things awkward (not a problem for nondirected donations), or because they learned that the recipient died from the procedure and that was too depressing. I asked that I not be told how my recipient did - most likely everything would go well, I was happy to keep assuming this, and more information could only make things worse. This request didn’t get communicated to the surgeon and he told me anyway - but luckily everything did go well.

-

My ex-girlfriend, who helped me figure out to ask for an MRI instead of a CT.

-

My wife, who was amazing through the whole process and didn’t freak out at all.

-

My parents, who freaked out somewhat less than they could have, all things considered. My father in particular, for giving good medical advice during my recovery.

-

My cousin Harvey and his wife Pam, who let me stay at their house on Long Island while I recovered, and their son Will, for visiting me in the hospital.

-

My uncle Mark for a quick nephrology consult.

-

Clara Collier, Georgia Ray, Taymon Beal, and Sam Rosen, for various forms of emotional support and offering to visit/stay with me in the hospital.

-

Elissa F, Miranda G, and especially Dylan Matthews, for talking to me about altruistic kidney donation, providing social proof of its acceptability, and letting me know the option existed. Probably there are other people in this category, sorry if I forgot you.

-

Fellow psychiatrist and ACX reader Dr. Brown, who covered my patients while I was away.

-

Josh Morrison of WaitlistZero (now of 1DaySooner), who encouraged me and gave me good advice.

-

The doctors, nurses, social workers, etc at Weill Cornell who did the actual work. You were all great. Except the guy who said getting my catheter out “won’t be bad, I promise”, I’m still mad at you.

-

The subset of doctors, nurses, social workers, etc at UCSF who were helpful during the intake process there and weren’t responsible for their final decision not to accept me.

-

Everyone who expected me to do things for them this past month and hasn’t made a fuss about me being out of commission for a few weeks. That includes all of you blog readers; sorry for the recent lack of articles. Normal business resumes next week, situation permitting.

-

Further perspective: I’m 38, which gives me a 2/million total chance of dying per day. So the likelihood that I would die during my kidney operation equals the likelihood that I would die during a randomly chosen two months of everyday life.

-

Maybe, kind of. Our knowledge of how radiation causes cancer comes primarily from Hiroshima and Nagasaki; we can follow survivors who were one mile, two miles, etc, from the center of the blast, calculate how much radiation exposure they sustained, and see how much cancer they got years later. But by the time we’re dealing with CAT scan levels of radiation, cancer levels are so close to background that it’s hard to adjust for possible confounders. So the first scientists to study the problem just drew a line through their high-radiation data points and extended it to the low radiation levels - ie if 1 Sievert caused one thousand extra cancers, probably 1 milli-Sievert would cause one extra cancer. This is called the Linear Dose No Threshold (LDNT) model, and has become a subject of intense and acrimonious debate. Some people think that at some very small dose, radiation stops being bad for you at all. Other people think maybe at low enough doses radiation is good for you - see this claim that the atomic bomb “elongated lifespan” in survivors far enough away from the blast. If this were true, CTs probably wouldn’t increase cancer risk at all. I didn’t consider myself knowledgeable enough to take a firm position, and I noticed eminent scientists on both sides, so I am using the more cautious estimate here.

-

I told them I had an aunt who died of radiation-induced cancer. It’s true, but I feel grubby for bringing her into this; I thought doctors would be more likely to listen to an emotional story than cold logic.

-

EAs have been debating the exact effectiveness of kidney donations for a long time. You can find good skeptical arguments by Jeff Kaufman and Derek Shiller, and good arguments in favor by Alexander Berger and Tom Ash.

-

Outside of Philosophy 101 thought experiments, there’s a nonprofit that will often reimburse you for lost wages from your donation.

-

Self-modifying into a person who can act boldly without social permission is a more general solution and has many other advantages. But the long version involves living a full life of accumulating moral wisdom, and the short version starts with removing guardrails that are there for good reasons.

-

But here are some practical points you might not already appreciate:

-

What’s a kidney donation mentor? I still don’t really know: I was told that I was assigned him as a mentor, and every so often he called me and asked if I was doing okay. I appreciate it, but hope it didn’t take him away from more important work.

-

Kidney donation is a complicated and exhausting process, and I couldn’t have done it without the help of many other people. Thanking them in no particular order: