Nobody Knows How Well Homework Works

Yesterday I wrote about bottlenecks to learning. I wanted to discuss the effectiveness of homework. If it works well, that would suggest students are bottlenecked on examples and repetition. If it works poorly, it would have to be something else.

Unfortunately, all the research on this (showcased in eg Cooper 2006) is terrible.

Most studies cited by both sides use “time spent doing homework” as the independent variable, then correlate it with test scores or grades. If students who do more time on homework get better test scores, they conclude homework works; otherwise, that it doesn’t.

One minor complaint about this methodology is that we don’t really know if anyone is reporting time spent on homework accurately. Cooper cites some studies showing that student-reported time-spent-on-homework correlates with test scores at a respectable r = 0.25. But in the same sample, parent-reported time-spent-on-homework correlates at close to zero. Cooper speculates that the students’ estimates are better than the parents’, and I think this makes sense - it’s easier to reduce a correlation by adding noise than to increase it - but in the end we don’t know. According to a Washington Post article, students in two very similar datasets reported very different amounts of time spent on homework - maybe because of the way they asked the question? I don’t know, self-report from schoolchildren seems fraught.

But this is the least of our problems. This methodology assumes that time spent on homework is a safe proxy for amount of homework. It isn’t. Students may spend less time on homework because they’re smart, find it easy, and can finish it very quickly. Or they might spend more time on homework because they love learning and care about the subject matter a lot. Or they might spend more time because they’re second-generation Asian immigrants with taskmaster parents who insist on it being perfect. Or they might spend less time because they’re in some kind of horrible living environment not conducive to sitting at a desk quietly. All of these make “time spent doing homework” a poor proxy for “amount of homework that teacher assigned” in a way that directly confounds a homework-test scores correlation. Most studies don’t bother to adjust for these factors. The ones that do choose a few of them haphazardly, make wild guesses about what model to use, and then come up with basically random results.

Both homework proponents (Harris Cooper) and opponents (Alfie Kohn) briefly nod to this problem, then take these studies seriously anyway. If you do that, you find that probably homework isn’t helpful in elementary school, but might be helpful during high school (though some people disagree with either half of that statement). But why would you take these seriously?

Are there any real randomized studies? Cooper finds six for his review article (page 17), none of which are published or peer-reviewed. Only one is randomized by students, and it contradicts itself about how random it actually was; the other five are cluster-randomized by classroom (which means they have very low effective sample size). Several are bungled in confusing ways. Still, these pretty consistently show a positive effect of homework with medium-to-high effect size. The one that might have been randomized by students (and so might possibly be okay) had an effect size of 0.39. Some of the cluster randomized ones that weren’t bungled too badly had effect sizes in the 0.9 range; the cluster randomization makes it hard to call this significant, but unofficially it seems impressive.

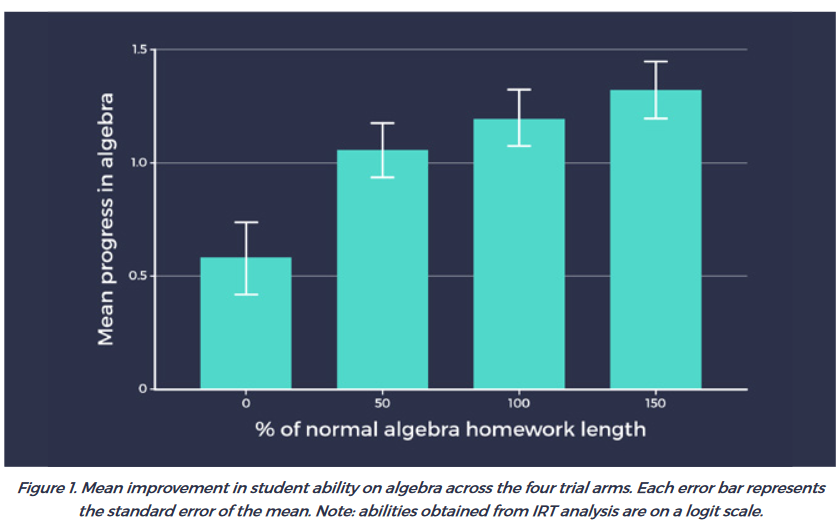

Since Cooper wrote his 2006 review, I was able to find one actually good, individually randomized study of homework, Nawaz and Welbourne. They took 368 students taking algebra classes using a digital platform, and randomly assigned them either 0%, 50%, 100%, or 150% of the ordinary homework load (corresponding to 0, 15, 30, or 45 minutes/night). Results:

The students with more homework did better, p < 0.0001. Looks solid. Probably 9th grade algebra homework is useful. But everyone already expected high school homework to be more useful than elementary school, and math homework to be more useful than other subjects. So it’s unclear if eg 4th grade reading homework would follow the same pattern.

Still, this is the one firm fact about homework which we have managed to produce in several million child-years of assigning it. For everything else, just go with your priors, I guess.