Non-Cognitive Skills For Educational Attainment Suggest Benefits Of Mental Illness Genes

Suppose you want to study the genetics of intelligence. You probably want a sample size in the six digits, and you can’t make a six digit number of people sit down and take IQ tests. Also, whenever you say “genetics” and “intelligence” in the same sentence, an angry mob shows up at your door. One solution is to switch to a more popular / less stressful line of work, like Mafia snitch or al-Qaeda second-in-command. But another solution is to use educational attainment.

“Educational attainment” means how far you got in school - did you graduate high school? Get halfway through college? Go to grad school? It’s a nice simple number that everyone already knows, and studies show it’s closely correlated with intelligence. This is the most common way people investigate cognitive genetics, and if you hear someone talk offhanded about finding “genes for intelligence”, they probably found genes for educational attainment.

Educational attainment is closely correlated with intelligence, but not perfectly correlated. How far you go in school depends not just on your IQ, but on other skills: how hard-working and motivated you are, how well you can cope with adversity - and arguably also less desirable qualities, like whether you so desperately seek societal approval that you’re willing to throw away your entire twenties on a PhD with no job prospects at the end of it. “Genes for educational attainment” will be a combination of genes for intelligence, and genes for this other stuff.

At some point, some geneticists just did the hard thing and found some actual genes for actual intelligence, separate from educational attainment. And if you have both the educational attainment genes and the intelligence genes, you can subtract the one from the other to find the non-intelligence-related genes that affect educational attainment in other ways. That’s the thought process behind Investigating the genetic architecture of noncognitive skills using GWAS-by-subtraction, by Demange et al (the “al” includes some researchers whose work has featured here before, like Paige Harden, Elliot Tucker-Drob, and Abdel Abdellaoiu).

They admit not doing a perfect job. Their genetic measure of non-cognitive skills (ie factors that affect educational attainment other than intelligence) was still correlated at r = 0.31 with IQ (higher than most things in social sciences ever correlate with anything). So take their results as directionally rather than exactly true. Still, what did they find?

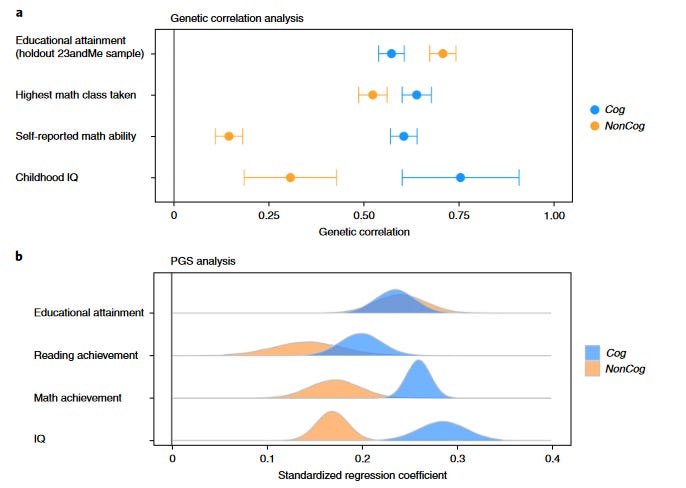

Unsurprisingly, both sets of skills contribute to educational attainment (that’s the point), and cognitive skills contribute more to IQ (that’s also the point). I was pretty surprised by how much more specifically “self-reported math ability” isolates cognitive ability compared to “highest math class taken”, but I guess people are good at self-assessment.

But the real fun is Figure 4:

EA FDR correction tries to impute the results from the main timeline, where Roosevelt was an effective altruist and diverted the resources of the Depression-era US into curing all diseases.

EA FDR correction tries to impute the results from the main timeline, where Roosevelt was an effective altruist and diverted the resources of the Depression-era US into curing all diseases.

This is correlation between the genes for cognitive/non-cognitive skills related to educational attainment, and the genes for something else (eg household income). Note that these are genetic correlations, so they’re not looking at your actual household income, they’re looking at the genes that would cause you to have a high household income. This is probably better since it avoids lots of possible confounders.

Both cognitive and non-cognitive skills increase your income a lot, no surprise there. Both sets of skills improve your lifespan (probably more educated people are better at judging health advice - get your COVID vaccine!) and prevent you from making bad decisions like teenage pregnancy, smoking, or excessive drinking.

The Big 5 personality factors are yet more evidence for stereotype accuracy: the intelligent people are more introverted, more disagreeable, and less conscientious; the people who do well for reasons other than intelligence are more likely to be extraverted, agreeable, and diligent. Both cognitive and non-cognitive skills are negatively correlated with neuroticism, which is not what I would have expected.

And then there’s mental illness.

I have been saying for years that I think some of the genes for some mental illnesses must have compensatory benefits. Everyone else said that was dumb, they’re mostly selected against and decrease IQ. But here we get a pretty clear picture of where this is and isn’t true.

Depression is just bad. I strongly recommend not having it. Don’t even have any risk genes, if you can avoid it. All of you people trying to come up with clever evolutionary benefits for depression, I still think you’re wrong, and so does the genetic correlation with cognitive and non-cognitive aspects of educational attainment.

ADHD is also just bad here. This doesn’t entirely match my previous beliefs; I think it’s helpful with a certain kind of high-stress task switching. But we can’t blame this study for not picking that up; it’s just using the giant bucket “non-cognitive skills that affect your ability to stay in school”, of which ADHD is definitely one and definitely net bad. I suspect that there are different forms of the syndrome that are vs. aren’t associated with low intelligence (and maybe some associated with high intelligence), but this is total speculation and this study tells us nothing about this one way or the other, except that it’s correlated with lower intelligence on net.

But genes for some other conditions increase non-cognitive skills related to educational attainment. Bipolar disorder, fine, something something manic creativity hard work. OCD, fine, it’s probably on a spectrum with OCPD which is on a spectrum with regular perfectionism. Autism, fine, probably a lot of Math PhDs.

But the big shock here is schizophrenia. As of last time I checked, the leading hypothesis was that schizophrenia genes were just really bad, evolutionary detritus that we hadn’t quite managed to weed out. And although they definitely decrease IQ, they seem to be good in other ways. Not with certainty: the correction for false discovery rate kills a lot of the effect (though this is the question I would have been most interested in before reading these results, so maybe I can ignore that?). But there’s at least a faint signal here.

I may write some future posts going down the very weird rabbit holes this result opens up.