Obscure Pregnancy Interventions: Much More Than You Wanted To Know

This is intended as a sequel to my old Biodeterminist’s Guide To Parenting. It’s less ambitious, in that it focuses only on pregnancy; but also more ambitious, in that it tries to be right. I wrote Biodeterminist’s Guide in 2012, before the replication crisis was well understood, and I had too low a bar for including random crazy hypotheses.

On the other hand, everyone else has too high a bar for including random crazy hypotheses! If you look at standard pregnancy advice, it’s all stuff like “take prenatal vitamins” and “avoid alcohol” and “don’t strike your abdomen repeatedly with blunt objects”. It’s fine , but it’s the equivalent of college counselors who say “get good grades and try hard on the SAT.” Meanwhile, there are tiger mothers who are making their kids play oboe 10 hours/day because they heard the Harvard music department has clout with Admissions and is short on oboists. What’s the pregnancy-advice version of that?

That’s what we’re doing here. Don’t take this as a list of things that you have to do, or (God forbid) that you should feel guilty for not doing. Take it as a list of the most extreme things you could do if you were neurotic and had no sense of proportion.

Here are my headline findings:

Going in order:

All The Normal Stuff (Tier 1)

This is a post on obscure pregnancy interventions. So I’ll be skipping over all the standard advice that OB/GYNs give: folate, iodine, alcohol, caffeine, cheese, whatever. That doesn’t mean you can skip it! The normal stuff is much more important than any of the obscure things on this list. Don’t even think about my recommendations until you’re doing all the normal stuff right.

I strongly recommend Emily Oster’s Expecting Better as a really good guide to the normal advice, including how much of it is really evidence-based vs. how much can be safely ignored.

Avoid Stress (Tier 1)

A pregnant woman’s stress is generally considered to have negative effects on the fetus.

The stress hormone cortisol can pass the placenta. Although the placenta usually tries to keep fetal cortisol exposure low, high enough levels can overwhelm this mechanism. See this page on maternal-fetal stress transfer for details. The most interesting study is Gitau et al, which looks at maternal and fetal cortisol levels during various scary medical procedures, and finds that even procedures that don’t affect the fetus cause elevations in fetal cortisol, presumably because they caused elevations in maternal cortisol and some of it crossed over.

Does this necessarily hurt fetal development? There are many studies showing it does, but before we get to them, three caveats.

First caveat: almost every topic we investigate, including this one, will be confounded by poverty. Poor mothers have more of most risk factors. They’re more exposed to toxic pollutants. They eat worse diets and take fewer supplements. They’re less likely to follow the latest fad health advice. And poor babies usually have worse outcomes: worse health, more behavioral problems, lower IQ. So if you ask “does this risk factor correlate with worse outcomes”, the answer is almost always yes (sometimes statisticians try to adjust away poverty and other confounding variables, but this never works). This is why only randomized controlled trials, or other studies that come up with clever ways around this problem, can be truly convincing.

Second caveat: almost every topic we investigate, including this one, will be confounded by genetics. Pregnant mothers will do something, and then their child will be a certain way, and people will want to say it was because they did the thing, but it might just be genetic. For example, consider the claim that maternal stress during pregnancy makes children develop anxiety disorders. You survey a thousand mothers, you see which ones are stressed during pregnancy, then thirty years later you check if those mothers’ kids have more anxiety disorders. They will, but anxiety disorders are genetic. If your mother was stressed during pregnancy, maybe it’s because she has a genetic tendency towards stress, which you inherit, and then you’re stressed all the time too. This can be more subtle: for example, what if we find that maternal stress decreases child IQ? It could be causal. Or it could be that low-IQ people make worse decisions, that means they end up in more stressful situations, and then pass those low-IQ genes on to their kids.

Third, closely related caveat: this whole field gets very political. You can use maternal stress to support “cycle of poverty” narratives where children in poor families “never had a chance”; their mothers were so stressed during pregnancy that their brains developed wrong, meaning they can’t be expected to succeed like other people. A lot of people are really attached to this idea, that makes them less willing to challenge studies that support it, and a lot of unusually bad ones get through.

With those three caveats in mind: sure, there are lots of studies showing that stress hurts fetal development. Probably the biggest is this study of 10,000 kids, which finds that maternal stress during pregnancy is correlated with increased likelihood that a kid will get ADHD. Could that just be the kind of confounders we talked about a second ago? Yeah, definitely.

But we also have causal studies. In 1998, there was a catastrophic blizzard in Quebec. People were left without electricity for weeks, roads were impassable, it all sounds very stressful. Scientists saw this as an opportunity, and this study compared outcomes for women who were pregnant during the blizzard with women who were pregnant a bit earlier or later. Five years later, they found that blizzard children had somewhat lower IQs. This seemed to depend on “objective stress” (ie how hard the blizzard hit them) and not on “subjective stress” (ie how much they were fretting about the blizzard) - which I guess leaves open the possibility that other blizzard-related problems (like food shortages) contributed.

In 2021, a Danish team compared mothers who had suffered bereavement during pregnancy to those who hadn’t. They found that the (presumably stressed) former group had a higher rate of intellectual disability among their offspring. This doesn’t perfectly screen out confounders: you can imagine that (for example) poorer mothers are more likely to have relatives with low life expectancy (or something). But I’m having trouble coming up with a great story for how this went wrong, and the sample size (two million people; they reviewed practically all births in Denmark over several decades) is very impressive.

Finally, there are various animal studies where researchers randomly inflict prenatal stress on rats and see what happens to their offspring. Usually the offspring do worse in some way. While animal studies don’t always directly translate into humans, this boosts my confidence that the potentially-confounded studies above are finding real effects.

I was on the fence about whether to rate this as Tier 1 or Tier 2. I decided on Tier 1 so I could start out with it, and you could start out with a warning that stressing out too much over little things can be counterproductive. Please keep that in mind as you continue to read this document.

Stay Away From CMV And Toxoplasma (Tier 1)

The number one cause of birth defects in developed countries is cytomegalovirus. About 50% of Americans are chronically infected, but the body eventually adjusts and this is low risk: the biggest danger comes if you get a new infection during pregnancy. The CDC says about 1/200 US babies are born with CMV, and about 1/5 of those will have a birth defect; I would be concerned that the others might also get subtle damage.

Cytomegalovirus is spread in bodily fluids, and you can avoid it by not exchanging bodily fluids with new people during pregnancy. That means kissing (though it’s probably fine to kiss your long-term monogamous partner - if they had it, you would have gotten it already) and unsanitary food-sharing. Young children are known to be terrible at keeping their bodily fluids to themselves, and daycares are known CMV hot spots. Practice good sanitary precautions when interacting with children and wash your hands regularly.

Toxoplasma is another chronic pathogen; about 20% of Americans have it at any given time. Like CMV, it is less dangerous if you have it long-term, but more dangerous if you’re first infected during pregnancy, so try to avoid that. A common route of transmission is cat feces; if you have a cat, try to keep it more indoors while you’re pregnant (so it has fewer chances to get the disease) and make someone else change the litterbox. Other risky behaviors are gardening (if you do, wear gloves) and eating undercooked meat. About 1/1,000 to 1/10,000 babies are born with obvious toxoplasma-related defects; I can’t tell whether this number leaves open the possibility that many more have subtler problems.

Embryo Selection (Tier 1)

During a typical course of in vitro fertilization, doctors give a woman hormones that cause her to make lots of eggs. Then they extract the eggs, fertilize them with sperm, pick one of the resulting embryos, and implant it in the uterus.

Which embryo do they pick? For a long time, the answer was “whichever looks good”; doctors would examine the embryos under a microscope and eyeball whether one looked healthier than another. It’s not clear how well this works.

More recently, scientists have learned to genotype embryos, the same way that eg 23andMe can genotype adult humans. If you have ten embryos and you need to implant one of them, you might as well pick the one with the best genes.

“Best genes” in what sense? If there’s a specific thing you’re trying to do - for example, your family has a history of breast cancer, and you want to avoid that - you can get the best genes relevant to that specific thing (ie lowest breast cancer risk). Otherwise you can use a weighted algorithm that just tries to give you the overall lowest risk of various bad things in proportion to how bad they are.

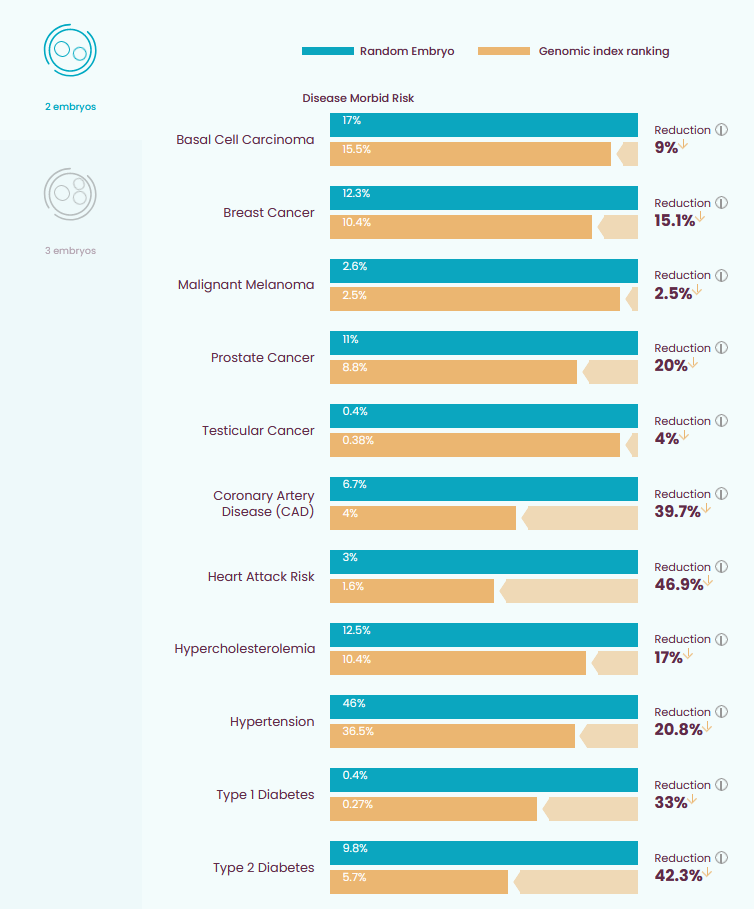

The image below (source: the embryo selection company Genomic Prediction) calculates the reduction in disease risk if you use the weighted algorithm on two embryos:

Embryo selection companies do not explicitly work with IQ, but some work with “risk of cognitive disability”, which I think is a different phrase pointing to the same concept (cognitive disability is just IQ below a certain threshold; your predicted risk of being below that threshold is just predicted IQ plus a confidence interval). Ability to detect embryo IQ is limited, and optimizing for this in particular will probably only gain you <1 - 3 IQ points (higher numbers for more embryos).

This technology hasn’t been tested yet, in the sense that it’s too new to collect data from any embryo-selected children. But it’s been tested in the sense of testing whether it can determine which of two already-born siblings was more likely to have had heart attacks, cancers, etc - and seems to work well. All of the science here is straightforward enough that I’m not even really sure what it would mean for this not to work.

Supplement Choline (Tier 2)

Choline is a nutrient found in eggs, meat, fish, soy, wheat, and certain vegetables. The body uses it to produce cell membranes, the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, and various other useful chemicals. Choline is an important building block of the prenatal nervous system, and studies have found that maternal choline levels correlate with offspring IQ.

Prenatal vitamins either don’t have choline, or have woefully inadequate amounts. Official recommendations say pregnant women get 450 mg choline/day, but the average woman only gets about 278 mg/day. According to the National Institute of Health, “approximately 90%–95% of pregnant women consume less choline than the AI.”

(here AI means “adequate intake” - this isn’t another one of those posts about the machines outcompeting us)

But it’s worse than this: I think the official recommendations are way too low. Studies suggest that the optimal amount of choline for pregnant women is around 930 mg/day.

Luckily, choline supplementation is simple and ethical, which means we can run randomized controlled trials. You can find a list of them in Table 1 of Korsmo:

Of these, the one I want to focus on is Caudill 2018. They give women either 480 or 930 mg choline during the third trimester, and find a significant effect (p = 0.02 - 0.03) on reaction time, sometimes used as a measure of infant cognitive development. This is a very small study (n = 26), but their results are consistent and it doesn’t look like they’re dredging for positives.

But also: when the body has extra choline, it converts it into a related useful molecule called betaine. During pregnancy, women have less betaine than usual, probably because they need choline so much that their body doesn’t have any to spare. So one clever way to check how much choline pregnant women need is to see how much you can give them before they start producing normal amounts of betaine again. Yan 2013 tries this, and finds that 480 mg isn’t enough but 930 mg is.

There are a couple of other weaker signs that 930 mg of choline is better than 480, which you can find scattered throughout the Korsmo review.

Why do all these studies use 480 and 930? I’m not sure. Could you do even better by supplementing more than 930? I don’t know. This study on whether choline protects against fetal alcohol exposure gave mothers 2g, with apparently impressive effects, including on followup four years later. There is no way to know whether this was a generic benefit of choline, a benefit of choline against fetal alcohol in particular, or whether the 2g did anything more than 930 mg would have. Daily doses of 3.5 grams or more are considered unsafe and seem to cause nausea, vomiting, sweating, “fishy body odor”, and production of a cardiotoxic chemical called TMAO.

How should you supplement choline? Most studies used choline chloride, which is not really available to civilian populations. Normal choline supplements can be choline bitartrate, phosphatidylcholine, alpha-GDP choline, and citicholine. The nootropics community is unanimous that alpha-GDP and citicholine are more appropriate for nootropics usage than the other types, but I can’t find a good technical explanation of why (“they get to the brain better” doesn’t count as technical). My guess is whatever’s going on there doesn’t matter in pregnancy, where you don’t necessarily want the choline going immediately to the (mother’s) brain. Most pregnancy vitamins that include choline use choline bitartrate, and this seems the most chemically similar to the choline chloride used in the studies, so probably this is safest.

A bunch of people (eg WebMD) say you should “avoid using citicholine” during pregnancy. This makes no sense to me and I’m guessing they don’t know what they’re talking about, but by Chesterton’s Fence maybe you should avoid this form.

I think the safest thing to do here is take somewhere between 900 and 2000 mg of choline bitatrate per day during pregnancy. Most studies focus on the late second and third trimesters, when the nervous system is forming.

Don’t Eat Too Much Licorice (Tier 2)

Licorice contains the dangerous-sounding chemical glycyrrhizin. Glycyrrhizin turns off the placental enzymes that limit the amount of maternal stress hormones that pass to the developing fetus. A study shows that mothers who eat lots of licorice during pregnancy have children with 7 points lower IQ (on average) than mothers with more restraint in their licorice consumption. Others studies show increased maternal blood pressure, increased risk of preterm birth. There are relatively few studies here compared to some other interventions, but the studies seem strong, the mechanism seems plausible, and there are fewer possible confounders than usual.

The study found effects at 500 mg glycyrrhizin per week, which corresponds to eating about two or three sticks of licorice per day for an entire pregnancy. Who does this? Finns, that’s who. All of these studies have been done in Finland, which is apparently a country of disgusting licorice junkies. I blame Santa Claus.

Still, there may be scattered non-Finns who eat this amount, or there may be subthreshold effects that the studies weren’t powered to measure. I suggest abstaining.

Only the sinister foreign “black licorice” contains glycyrrhizin. The red licorice eaten by normal red-blooded Americans is (as per American tradition) made out of corn syrup derivatives with no real licorice whatsoever, and should be fine.

Avoid Painkillers, Including Tylenol (Tier 2)

Doctors have been gradually chipping away at pregnant women’s ability to use pain medication. First it was “don’t use opioids, your baby could have birth defects”. Then it was “and don’t use ibuprofen, your baby could have kidney problems”. Then it was “and don’t use too much aspirin either, your baby could get cardiovascular problems”. That left Tylenol (aka Panadol, paracetamol, acetaminophen, etc) as the only pregnancy-safe pain reliever. Well, bad news…

Last year, Nature Reviews Endocrinology published Consensus Statement: Paracetamol Use In Pregnancy - A Call For Precautionary Action, by ninety-one leading scientists. It argued that Tylenol use during pregnancy might cause neurodevelopmental and urogenital disorders in children. They argue that Tylenol babies have higher risk of abnormal hormone profiles, abnormal urinary tract development, and ADHD. What’s their evidence?

Many rat studies have shown negative effects of prenatal Tylenol, usually at levels much higher than a human would take (eg 1, 2, 3). Most of these studies are small and weak - and did you know that Tylenol is a deadly poison to cats? Doesn’t really bode well for inter-animal transferability of results. Still, these studies exist and are numerous.

Other studies ask women how much Tylenol they took when they were pregnant, then try to correlate it with offspring outcomes. The Consensus Statement lists 29 of these studies, and says 26 / 29 found evidence of harm. A typical study is Chen 2018, where researchers identify 950 kids with ADHD and 3800 kids without, and compare (using health system records) how likely their mothers were to have used Tylenol (finding that the ADHD moms were about 25% more likely). Even more sophisticated is Ji 2020, which found that “[umbilical] cord biomarkers of fetal exposure to acetaminophen were associated with significantly increased risk of childhood ADHD and ASD in a dose-response fashion.”

ADHD is very genetic, so we should be alert for possible confounders like “ADHD moms get more stressed, have more headaches, and so use more Tylenol, and then their kids inherit their ADHD”. But we have two signs that this isn’t what’s going on here. First, a (relatively weak) finding that mothers who took the alternate headache medication ibuprofen did not have kids with more ADHD. And second, two studies (1, 2) finding that taking Tylenol immediately after or immediately before pregnancy has no effect - if it was just a proxy for class or ADHD you’d expect the same correlation regardless of the woman’s pregnancy status. All of this makes the effect look real.

What about: people often use Tylenol for fevers, and having a fever (usually indicating infection) during pregnancy sounds pretty bad. Are we sure that the Tylenol isn’t just a marker, and it’s the fever/infection causing the ADHD? These people claim to have ruled that out - they say they asked why people used Tylenol, and the people using it for pain had the same increased risk as the people using it for fever - but it seems like kind of an afterthought for them and they don’t really show their work. I would like to see someone do a study focusing on this; it ought to be easy, and might be very important.

One study does find some evidence that the effect is due to confounders. It looks at mothers with two children who used Tylenol during one of their pregnancies but not the other. Both children had usually high levels of ADHD, suggesting that Tylenol is standing in for some other confounding factor. This seems to directly contradict the early studies showing that Tylenol use before or after pregnancy has no effect, since “during your sibling’s pregnancy” is just an extreme version of before vs. after your own. I have no good explanation for this.

Emily Oster reviewed this literature and called it “a grey area”. I agree. I don’t think you’re a monster if you decide to use Tylenol during your pregnancy, but I don’t think you’d be insane not to, either.

Of note, several studies find that short-term Tylenol use during pregnancy (< 8 days) is fine. One study even found mildly beneficial effects (it suggests that maybe people who use a little Tylenol are being proactive against treating fevers). You can do what you want with this information.

But remember: all the other painkillers, eg ibuprofen, are even worse. So what if you have pain during pregnancy?

| [](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fea5dba0a-765e-43bc-aeec-e18588d037f5_800x450.jpeg) |

Eat Fish (Tier 3)

The FDA recommends that pregnant women eat at least 8 ounces of fish per week in order to get omega-3 fats, which seem important in building the fetal nervous system. There’s good theoretical science behind this, and lots of observational studies like this one, which follows 12,000 women and finds that those who ate more than 340g of fish per week had smarter babies.

But randomized controlled trials of omega-3 supplementation continually come up short. This meta-analysis claims that zero of 25 trials found a positive result. My literature review wasn’t quite that disappointing - for example, these people are able to find obviously fake positive results after doing enough p-hacking - but I agree the field looks pretty dismal.

There are two possibilities. First, the observational studies are confounded - most likely, richer people eat more fish, and their attempts to control for poverty fail. But also, all the observational trials ask about eating fish, and all the randomized trials supplement with fish oil. So a second possibility is that real fish is good for you but fish oil isn’t. This isn’t quite as much of a stretch as you might think; sometimes foods have complicated profiles of nutrients which support one another’s absorption, or the beneficial nutrient isn’t the one we think, or something. But it is kind of a stretch, especially when we already know how frequently confounded these kinds of studies are.

Here’s a hot take which as far as I know nobody’s ever made before: maybe fish are good because of choline. We already know choline is important to fetal development and undersupplied in the typical maternal diet. And fish are loaded with choline. This would neatly explain why fish are good for you but omega-3 supplementation isn’t. Hopefully you’re already supplementing choline (see above), so fish wouldn’t be especially important after that.

I’m still giving this Tier 3, because a lot of smart people think it’s important, because I’m not 100% sure of the above, and because whatever, it’s just fish. Make sure to eat the species with less mercury; Emily Oster’s book will give you the details.

Air Filter (Tier 3)

One recent theme in public health has been “air pollution is really bad for you”. Whenever people test to see if air pollution has some bad outcome, the answer is always yes. Sometimes this is suspicious: does putting an air filter in a classroom really raise grades as much as halving the class size? Does putting an air purifier in a sociology laboratory really raise interpersonal trust on prisoners’ dilemma games? Does putting an air purifier in a church really make parishioners half again as likely to go to Heaven? This has to be one of those annoying science fads like stereotype threat or priming, right?

Still, studies show air pollution is bad for pregnant women. Here’s an observational study linking prenatal air pollution exposure to offspring cognitive and behavioral issues. Could this be confounded by poverty? Obviously yes, poor people are forced to live in worse neighborhoods with more pollution.

There’s only one controlled trial here: researchers in the important science hub of Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia randomized pregnant women to receive / not receive free air purifiers, then waited to check the birth weights of their babies (higher birth weights usually = healthier). The results were confusing; the women who got the air purifiers were more likely to have pre-term births, pre-term births are always lower birth weight, but among women who gave birth at term, the ones who got the air purifiers had heavier (= healthier?) babies.

The researchers speculated that the air purifiers made the women and fetuses healthier, which meant that some unusually sick fetuses who would have been miscarried in the control group survived in the experimental group and were born pre-term instead. Counting all fetuses including the dead ones, the experimental group was healthier; counting only living fetuses, there was no difference. I think it’s fair to count death as a bad outcome, so I will reluctantly accept this as a positive study. It’s still the only one, though.

The study also found that two air purifiers were (nonsignificantly) better than one, so feel free to go wild and surround yourself with a ring of air-purifiers, like some kind of demonological warding circle.

See also this Less Wrong post on the study mentioned above.

High Fruit Diet / Supplement Carotenoids (Tier 3)

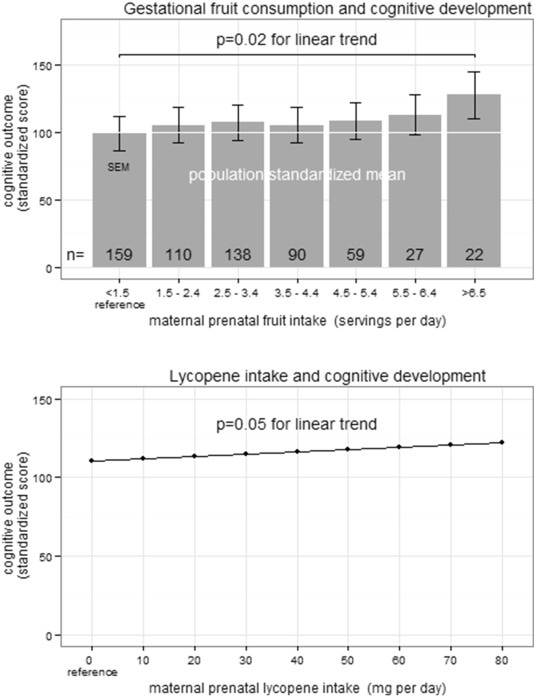

Getting bored? Don’t. Bolduc 2016 found that women who ate more than seven servings of fruit a day while pregnant had offspring with +5 IQ points.

This graph is even more extreme than my statement above - I don’t know why the discrepancy - and seems to imply that eating 80 mg lycopene per day takes your kid from completely normal all the way to Ivy League material.

This graph is even more extreme than my statement above - I don’t know why the discrepancy - and seems to imply that eating 80 mg lycopene per day takes your kid from completely normal all the way to Ivy League material.

So, this has to be false, right? I would be shocked if it wasn’t. The usual way for things like this to be false is as covert class markers: rich people eat more fruit, and also have lots of other advantages, and so their kids turn out smarter. But the study finds fruit is actually much more important than social class (the average rich person isn’t Ivy League material, but the average 80-mg-lycopene-eater is). If we believe this study, maybe being rich only contributes to success insofar as it makes you eat more fruit!

The authors seem suitably weirded out by their results, and try an animal experiment on fruit flies (come on, fruit flies? is that cheating?) They find that if they give pregnant fruit flies lots of fruit, their offspring do better at whatever the fruit fly equivalent of an IQ test is. They suggest a mechanism vaguely based on lycopene → something something cAMP → cognitive development.

The closest I can find to a replication is Mahmassani 2021. Instead of lycopene, it focuses on two closely related nutrients in fruit called lutein and zeaxanthin. They find women in the top quartile of L&Z intake have offspring about 3 IQ points higher than in the lowest - which, they note, is the same difference as breast- vs. bottle-fed infants. One strength of their study was that everyone involved was socioeconomically advantaged (they were in a wealthy area), so there’s less room for fruit to be a class marker. Still, this is a weak study design and I’m still really concerned about this confounder.

There are various scientific reasons to think carotenoids like lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin should be beneficial to developing nervous systems. Some dubious studies have found they help cognition in the elderly. There is some evidence that pregnancy depletes maternal stores of lutein and zeaxanthin (though not lycopene) in a way that implies the mother’s body is putting a lot of effort into getting them into the baby.

Overall this is a spectacularly large result, but it’s based on 1-2 observational studies without good defenses against confounding. I think it probably won’t be true in the end, but you might as well eat lots of fruit and supplement with lutein/zeaxanthin, which are safe and easily available.

Birth Month Selection (Tier 3)

Some studies find effects of birth month on various traits, but they disagree in which direction.

Before we go over evidence, why would this possibly be true? There are at least two reasons. First, winter is flu season, and more generically the season for almost every infectious disease. Prenatal infections can be bad for kids, and maybe getting them at one part of pregnancy instead of another can be especially bad. Second, a lot of places have school cutoff dates: if you’re born just before the cutoff, you’re the youngest kid in your class, but if you’re born just after the cutoff, you’re the oldest. There might be advantages to being the oldest or youngest kid in your class, and usually being bigger/smaller/faster/slower than everyone you know.

But the evidence here is pretty confusing.

— It’s well-established that schizophrenia risk varies with birth month, reaching its minimum in September and rising to a peak 10 - 20% higher in March (this and all further data in this section will be for the Northern Hemisphere only). Scientists have investigated a number of causes including Vitamin D levels, but I’m pretty convinced it’s infection risk.

— The literature on autism is much less clear, but preliminarily shows the opposite (1, 2, 3) - lowest risk in March, highest in September. I have to admit I am really surprised by this, although I guess it’s consistent with the laundry list of weird opposites between autism and schizophrenia.

— Large studies of IQ (1, 2) tend to find it’s about one point lower in winter-spring babies than summer-fall. At least half of this, and maybe all of it, is confounding where less intelligent mothers are more likely to give birth in winter (why? there’s a slightly tendency among women who plan their pregnancies to want babies in summer; maybe smarter women are better at planning?)

— Extremely famous and accomplished people are significantly more likely to be born in summer. See for example this graph of Nobelists (source):

. . . or this graph of other geniuses (source):

N is a different set of Nobelists, F is Fields Medalists (ie great mathematicians), T is a Time Magazine list of famous people, and M is a group of great musicians.

N is a different set of Nobelists, F is Fields Medalists (ie great mathematicians), T is a Time Magazine list of famous people, and M is a group of great musicians.

These effects usually hover on the border of significance; I am tempted to round them up because they should be using time trends rather than point estimates, and because you can add up different groups to get a bigger sample size.

This kind of weird paper that doesn’t do a great job listing sources says that Hans Eysenck looked through all people featured in Encyclopedia Britannica and found excess births in winter ; it then posits (kind of reflecting the graph above) that creative geniuses are more likely to be born in winter, and scientific geniuses in summer.

I realize this sounds like the most outrageous astrology, but I kind of buy it. It’s very well established that schizophrenics are more often born in winter, and the research is leaning pretty hard toward autistic people being more often born in summer. This matches the strong tendency in an otherwise boring graph for great musicians to be born in winter and great mathematicians to be born in summer. Weak research suggests that left-handers are more often born in spring, and right-handers in fall, and left-handedness is correlated with schizophrenia and rumored (though studies are poor) to be correlated with creativity.

My guess is that increased infection risk during winter causes babies born during those months to have slightly less “normal” brains, which makes them a bit less likely to excel at science and more likely to excel at creative pursuits. I expect this effect is very, very small, probably less than d = 0.1.

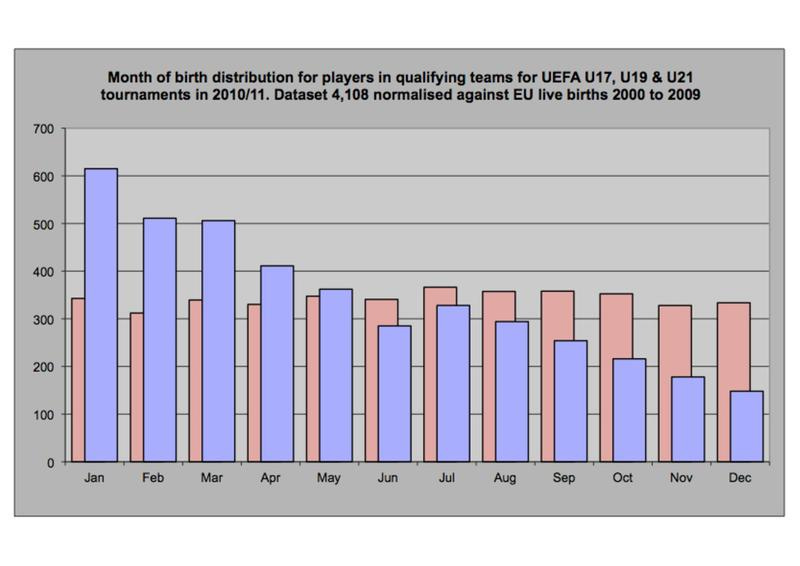

— Children born just after a school/league age cutoff do better at sports. This is a large effect, see eg this graph (source):

This is the age distribution of 10 year old soccer tournament players (blue) vs. all 10 year olds (red). Kids born in January are 4x likelier to play soccer at this relatively high level than kids born in December. Presumably if you start soccer at 6 years old, the kids who are 6.99 are a lot better than the kids who are 6.01, and so more likely to stick around and develop good soccer-related self-esteem. I’m not sure this graph (age 10) is about soccer-related self-esteem and stick-to-it-ness vs. it’s still better to be 10.99 than 10.01, but it sure is a big effect.

Studies generally find this still applies at the professional level, though there are some confusing details. I previously cited this piece, which shows the National Hockey League has twice as many players born in the first half of the year than the second, but this study suggests that’s since declined to only about 30% more; professional soccer seems to have about the same effect size. Some sources say that the effect disappears or even reverses at the very highest level, and may not exist at all in women’s sports.

— You might expect a similar effect in intellectual activities: a 6.99 year old child might be the smartest person in their class, and be encouraged to continue learning. This seems at least partly true. Here’s the birth month of a set of Oxford graduates (source):

Needless to say, the British academic year cutoff is between August and September.

(could this explain the Nobel Prize results? I don’t think so. Look at the Nobelist graph above. There’s basically no difference between August and September - which is pretty surprising, given that you’d expect graduating Oxford to be a useful step on the path to a Nobel)

(could this explain the IQ results? No, the authors looked for this effect, didn’t find it, and were pretty sure it was mostly maternal confounding)

— Looking at income, there are a lot of effects that all cancel out. This study finds later-borns do worse their first year on the labor market, for much the same reason later-born soccer players and Oxford students do worse. But they have an extra year on the labor market compared to earlier-borns, meaning they get more experience by the same age. Over the course of a lifetime there is no significant difference.

Overall conclusion for this section: if you want your kid to do well in professional sports, arrange for them to be born just after the cutoff (probably New Years). You can slightly improve your kid’s likelihood of getting into a good college by arranging them to be born just after the academic year cutoff (it varies; check your local school rules). You can probably shift your kid’s likelihood of schizophrenia and artistic achievement vs. autism and scientific achievement very slightly by arranging for them to be born in winter or summer, respectively. None of these interventions really seem worthwhile unless you have a family history of something or very specific preferences.

Activated Alumina Water Filter (Tier 3)

Fluoride is a chemical which is added to water to promote Commun . . . sorry, to protect against tooth decay. Very high levels of fluoride are clearly toxic; this is most commonly observed in rural China and India, which have a combination of naturally high fluoride groundwater and various bad practices. In India, severe fluoride excess can present as bone problems.

Studies show fluoride causes brain damage in rats, but these studies are generally at 10-100x normal human doses, with studies closer to normal human levels not showing a clear effect.

Some studies from India and China suggest children prenatally exposed to high fluoride levels have lower IQ, with a Chinese meta-analysis of 27 studies finding a 0.5 IQ point difference between the most and least exposed regions.

Can fluoride decrease IQ at the relatively low levels seen in developed world water systems? A Mexican study, Chinese study, and Canadian study all say yes, usually finding an effect of 1-2 IQ points between fluoridated and unfluoridated regions (usually they don’t compare this directly, but they give urinary fluoride curves we can use to calculate this).

I am really skeptical of all these. The Chinese study finds the effect is mediated by single genes in exactly the way that nothing ever is in real life. The Canadian study is done by a team who do a lot of fluoride studies and sometimes find results so large that they’re basically impossible - like this one finding a 6 to 9 IQ point decrease. Under some plausible assumptions, this explains more environmental IQ variance than actually exists!

Many of these studies were done by the same Canadian team, and lots of other people don’t like those people. You can read about “the fluoride wars” here.

Some economists did a very economist-y study where they looked at everyone in Sweden, tried to calculate how much fluoride they’d been exposed to over their lives, and correlated that with their lifetime income. They find no effect, but they weren’t looking at prenatal fluoride, so it probably doesn’t address our question very well.

Overall I am skeptical of these results, but more on a hunch than because I can pinpoint the exact flaw in the study. If we were to take them seriously, what would we do? It looks like activated alumina water filters like this one remove most fluoride, so filtering water when pregnant might be a reasonable step.

Avoid Early Induction (Tier 3)

From the subreddit: An Alternate Approach To Improve Your Child’s IQ.

“Wackademic” says that preterm birth is bad for children’s future health, developmental milestones, and - yes - IQ. But is birth early in term (eg week 37) worse than birth later in term (eg week 40)?

Yang 2010 says yes! IQ (at least as measured in 6 year old Belarussian children) peaks in children born between 39-41 weeks; they’re 1.7 points smarter than kids born at 37 weeks, and 0.4 points (nonsignificant) smarter than kids born at 38. After 41 weeks, the kids start getting less smart again, probably because a pregnancy lasting this long means something has gone wrong. This review confirms Yang’s findings.

So how do you ensure a 40 (rather than 37) week pregnancy? Wackademic suggests progesterone therapy and cervical cerclage (where you sew the cervix shut), both of which have some studies in support.

But, hapea, a real OB/GYN, comments:

I’m familiar with the literature about cognitive outcomes in early term. However, thus is still a very niche subject without honestly high quality trials and a low effect size. I wish I could find the paper right now and I’ll update if I do but there is some quite convincing literature that in terms of risk of death in utero vs death in the neonatal period the best time to deliver is 38-39 weeks. The ARRIVE TRIAL is a landmark trial as well regarding induction at 39 week which has led to more OBs offering 39 week elective inductions, when previous praxis was to wait until 41-42. You’ll note that even at 40 weeks gestation, you have a relative risk of 1.5 of fetal death compared to 39 weeks.

OK, on to preventing preterm labor. None of these things you listed are really going to effectively prevent preterm labor in low risk women. In terms of progesterone- there are two types, IM and vaginal. At the beginning of my training we offered IM progesterone to everyone with a history of preterm delivery. We did this because the initial data had been promising, however when they did larger quality studies they basically found it has no effect. Vaginal progesterone is still used to recent preterm birth in women with short cervixes, but even there its efficacy may be overstated.

In terms of cerclage, we reserve this intervention for the women at highest risk of preterm birth (usually history of preterm delivery <34 weeks and other criteria because of the high risk of complications associated. You have anesthetic complications, risk of membrane rupture, bleeding, even risk of fetal death. Overall it can actually be helpful in preventing preterm birth but only in high risk women. This is the relevant Cochrane review. It’s a fairly major procedure and should not be undertaken lightly.

So I think we’re currently at the point where, although there’s weak evidence that birth at full term is slightly better than birth at early term, there aren’t safe enough birth-delaying technologies for it to be worth trying.

Also, these studies are correlational, which means we don’t know whether forcing a child that “wants” to come out at 37 weeks to instead come out at 40 helps, hurts, or does nothing. I don’t have a good sense how the body decides to give birth at one time rather than another, but I’d be nervous about messing with it.

I think the main takeaway here is that if a doctor asks if you want early induction, you’re trading off a slightly lower risk of fetal death for a couple of IQ points, and you can make that decision based on your own fetal death risk and values. Inducing earlier than 38 weeks seems like a bad idea unless there’s a specific reason, and waiting longer than 40 weeks doesn’t seem to have any further benefits.

Be Careful With Plastics/Reciepts (Tier 3)

Endocrine disruptors are a broad class of chemicals with scary names like “phthalates” and “perfluoroalkyl substance” that alter natural hormones. Many are found in plastic, and absorbed when people eat food that has been in close contact with plastic packaging. There is some evidence that exposure during pregnancy is bad for the fetus. Braun 2017 reviews several classes of these chemicals. For example:

Six publications from four prospective cohort studies report that prenatal exposure to several different phthalates is associated with ADHD behaviors,59,60,93,94 autistic behaviors,61 reduced mental and psychomotor development,60,62 emotional problems,60 and reduced IQ.63 In a prospective cohort of 328 mothers, the reductions in child IQ associated with increasing maternal urinary phthalate concentrations were as large as or larger than the cognitive decrements observed with childhood lead exposure (5th vs. 1st quintile: 7-points; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2, 11).3,63 It is important to note that three other publications did not find associations between prenatal phthalate exposure and child neurobehavior.64–66

These have the usual problems with confounders - for example, might poor people eat more plastic-packaged food, or live closer to polluting plastic factories? They also have some extra problems: most people get “bundled” exposure to a variety of plastic-related pollutants, making it hard to figure out if any individual chemical is worse than any other.

Still, it is probably fair to want to limit exposure to these substances. Braun suggests:

Presently, there are no evidence-based methods for reducing EDC exposures, but there are some general recommendations that clinicians could give to concerned patients. For EDCs found in the diet (e.g., BPA, DEHP, and PFAS), eating a balanced diet may be one way to avoid exposure from any one foodstuff, but this advice has not been empirically evaluated. Intervention studies show that decreasing or eliminating canned or packaged food consumption is effective at reducing BPA and DEHP exposure.73,100 An intervention study showed that handling BPA-containing thermal receipts was an important route of exposure and that wearing gloves could reduce BPA exposure from this route.102 Another study found some evidence that children who have handle thermal receipts may have higher BPA exposure.109

Individuals may be able to reduce their exposure to DEP and DnBP by reducing or eliminating the use of some lotions, cosmetics, and colognes/perfumes.76,212 However, there are no requirements for personal care products to include these phthalates in their ingredient list, making it difficult to avoid this source of exposure. Individuals can reduce triclosan exposure by avoiding triclosan-containing toothpastes. However, because triclosan-containing toothpastes are clinically indicated for some individuals, the benefits and risk of continued use should consider the specific conditions and susceptibilities of the individual (e.g., pregnancy). Finally, granular activated carbon water filtration systems may be effective at reducing PFAS exposure when consuming PFAS contaminated water,213 but this may have a minimal effect on total PFAS body burden when diet is the predominant source of PFAS exposure.214

So: eat a balanced diet, avoid plastic-packaged and canned food, avoid some lotions and toothpastes, filter your water, and . . . avoid touching receipts? Apparently, yes. Receipts contain an endocrine disruptor called bisphenol A.

Do people actually get meaningful amounts of this through receipt-touching? Ehrlich 2014 says yes, but subjects were asked to handle receipts “continuously for 2 hours” (!). This sure did increase their urinary BPA concentration:

. . . but this level of receipt handling sounds more typical of cashiers than ordinary customers.

Stacy 2016 finds a marginal effect on the border of significance in children, comparing those who did vs. didn’t handle receipts in the past 24 hours, which is surprising since I would expect people to do a bad job self-reporting that.

Bernier 2017 examines receipt-holding in the wild and estimates that it would cause the absorption of “51 ng/kg/day”, a number which means as much to me as it does to you. Notably, they find that their subjects hold the receipt for an average of 11 minutes, probably because they are waiting in line on a cafeteria.

Hormann 2014 finds that under some assumptions, BPA can reach levels potentially associated with toxicity from receipt-holding alone; their subjects held the receipt for 4 minutes.

I think it’s reasonable to be cautious about receipt-holding, but I was surprised by how long everyone in these studies held receipts for. Who (besides cashiers) does anything except touch it long enough to put it in a pocket, and then long enough to transfer it from a pocket to a trash can? As yet there is no evidence either way about whether this kind of very casual touching is dangerous.

Supplement Vitamin D (Tier 4)

Various studies (eg Melough 2021) find that higher maternal vitamin D levels are associated with better neurocognitive development. Nobody has done anything even close to the effort it would take to determine if this were causal, and I’m pretty sure it isn’t.

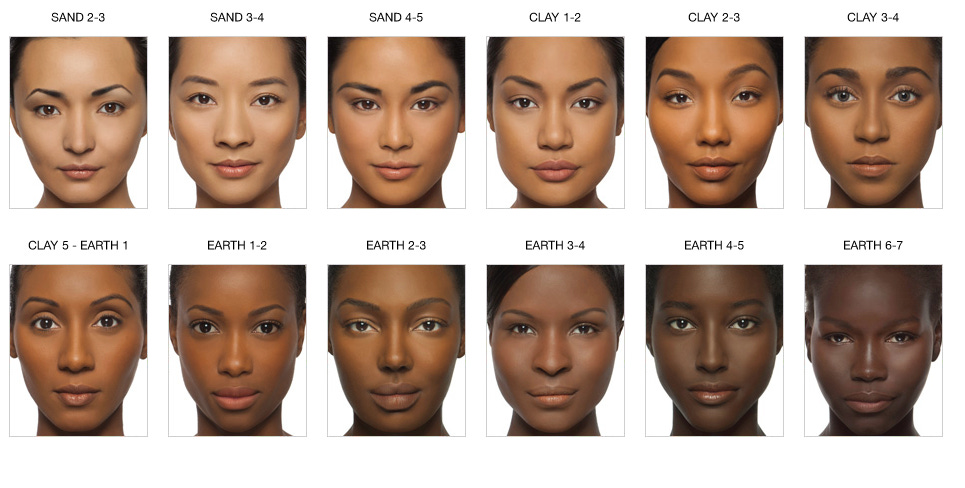

Remember, all of these are confounded by poverty: richer children are more likely to be healthy and have high educational attainment. White people are generally richer than black people, and have much higher vitamin D levels (the whole point of white skin is to allow enough sunlight through to produce vitamin D in colder climes). So this is just finding that white children do better than black children in various ways, which shouldn’t come as a surprise.

But don’t these studies control for race? Yes - they ask people to identify as “white” or “black”, then control for that. That’s totally inadequate:

Different white and black people have different shades of white and black skin. And sociologists have pretty conclusively shown that even within a racial category, people with darker skin encounter more prejudice and have worse outcomes (“colorism”). Another way to think of this is that most black people are part white, and the higher their white fraction, the lighter their skin, the higher their vitamin D and the closer their outcomes are to white people’s.

I can’t find any exploration of prenatal vitamin D that avoids this pitfall. I’m sure that clinical vitamin D deficiency (very rare) is bad for everyone, including developing fetuses. I’m less convinced that the kind of variation you’ll see in a normal population will have much effect. Still, vitamins are good for you and you might as well take more. So fine, take vitamin D when you’re pregnant. It’ll probably be in your prenatal vitamins anyway.

Paternal Interventions (Tier 4)

Is there anything fathers can do to have better sperm?

Yes: they can be young. The paternal age effect says that children of older fathers do worse in various ways. They have (slightly) higher risk of psychiatric disease and worse health outcomes.

This makes sense. Every year, our cells divide a bunch of times. Most of those divisions go well, but a few of them introduce new copy errors (mutations) into the genome. An older person has more time to accumulate mutations, so their DNA will be “worse”. Worse DNA can cause many different diseases, but is especially likely to cause psychiatric disease since there are so many genes involved in brain function.

The most replicated finding is autism, where (according to UpToDate):

A small but statistically significant association between advancing paternal age and risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has also been observed [101-106]. As an example, a dose-response meta-analysis of 27 observational studies reported that a 10-year increase in paternal age resulted in a 21 percent increased risk of autism in the child [107]. A study of over 14,000 Dutch patients reported that, compared with fathers under age 20, males over age 40 who father children were 3.3 times as likely to have a child affected with ASD [108]. Another study in Israel, which drew data from over 130,000 couples, reported that, compared with fathers under age 30, males over the age of 40 were 5.75 times as likely to have an offspring with ASD [101]. This may be related to de novo spontaneous mutations and/or alterations in genetic imprinting.

And schizophrenia:

Multiple studies have reported an increased risk of schizophrenia in children conceived by fathers of advanced paternal age [46,91-94]. Older paternal age has also been associated with younger age of symptom onset in affected children [95,96]. The risk appears to be transcultural [97]. The causal mechanism is hypothesized to involve mutational errors during spermatogenesis [98]. However, the overall incidence of schizophrenia is low, at approximately 1.5 per 10,000 people [99]. Thus, even in families with a family history of psychiatric disorder, the overall increased risk from advanced paternal age is negligible.

In one study, the relative risk of schizophrenia in children of older fathers compared with those younger than age 25 increased in each five-year age group, reaching 2.02 (95% CI 1.17-3.51) and 2.96 (95% CI 1.60-5.47) in offspring of males ages 45 to 49 and ≥50 years, respectively [91]. The actual incidence of schizophrenia in offspring at age 21 according to the fathers’ age at their birth was: age <25 years (2.5 per 1000), 25 to 29 (3.5 per 1000), 30 to 34 (3.7 per 1000), 35 to 39 (4.4 per 1000), 40 to 44 (4.6 per 1000), 45 to 49 (5 per 1000), and ≥50 years (11.4 per 1000). For comparison, the baseline incidence of schizophrenia ranges from 10.2 to 22 per 100,000 people per year [100]. In another series, the overall hazard ratio for each 10-year increase in paternal age was 1.47 (95% CI 1.23-1.76)

Effects on IQ are less clear:

There is limited information on the relationship between advanced paternal age neurocognitive ability in offspring, and the available data conflict, which makes counseling patients challenging. In a study of over 33,000 children from the United States Collaborative Perinatal Project, advanced paternal age was associated with modest negative effects on neurocognitive function, as assessed by Bayley scales (except the Bayley Motor score), Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale, Graham-Ernhart Block Sort Test, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, and Wide Range Achievement Test [88]. In the same study, advanced maternal age was generally associated with better scores on these tests. Of note, these tests were administered to children at ages eight months, four years, and seven years. In contrast, a population-based study of over 565,000 Swedish brothers whose IQ was measured during conscription examinations (ages 17 to 20), advanced paternal age did not impact offspring IQ, but advanced maternal age was associated with a slight worsening of IQ [89]. For specific learning differences, one report linked advanced paternal age and dyslexia in male offspring [90]. Further studies using consistent methodologies and neurocognitive tests are needed to address this issue.

Might these effects be because unhealthy or mentally ill men take longer to find mates, and so are older when they have children (who presumably inherit those traits)? Yes, this probably explains part of the effect. Gratten et al argue that Risk of psychiatric illness from advanced paternal age is not predominantly from de novo mutations; buried in the paper is a claim that, on certain models and for certain conditions, the mutations only cause about 10-20% of the observed effect. Can we throw out the caveats and take “10 - 20%” as our headline number? Not really. For some diseases that we know are because of de novo mutations, they might be 100% of the effect; for other diseases with lots of different causes, they might be very low. Some diseases might have multiple causes: usually severe autism is caused by de novo mutations, and mild autism is caused by inherited SNPs. For IQ in particular, smarter fathers usually wait longer to have children, so the estimate of the paternal age effect is biased down. Realistically all of this is pretty minimal on an individual level, although on the population level it probably adds a few percent to prevalence of all of these things.

Given that you can’t get younger, what can you do about this?

David Sinclair claims that nicotinamide mononucleotide supplementation can rewind the epigenetic clock. Would this reverse paternal age effects? I think no, for two reasons. First, paternal age effects are more likely to be because of genetic damage than epigenetic damage. Second, in the one mouse experiment where they tried this, NMN “reduced sperm count, vitality and increased sperm oxidative DNA damage, which was associated with increased NAD+ in testes”, though not consistently.

Is there anything else fathers can do? I would be surprised if there was: the fertilized egg usually undergoes a pretty complete epigenetic reset. Here is a very unconvincing mouse study suggesting that paternal low-protein diet is bad for children. Here is another study showing that paternal low folate increases the risk of birth defects. I’m very skeptical of all of this, but fathers might want to be generally healthy just in case.

There is a large literature on what increases sperm count, sperm motility, etc, but I haven’t been able to find good evidence that this affects offspring characteristics, as opposed to just chance of getting a mate pregnant.

Older mothers don’t get the same type of de novo mutations in their gametes, but they seem to do badly in other ways, especially a higher risk of aneuploidies (eg Down’s syndrome).

Abdominal Decompression (Tier 4)

During pregnancy, the growing fetus compresses the maternal abdomen and is compressed in turn. South African doctor O. S. Heynes invented a suction machine that would suck the abdomen outwards, making it larger and roomier.

(source)

(source)

The original plan was to use it to ease labor pains, but Heynes thought it might also help with backache and some complications of late pregnancy, so he encouraged women to take the machine home and use it for about 30 minutes daily during the last few weeks of pregnancy. This caught on, and in its heyday in the late 1960s and early 1970s, about 10,000 women - mostly in South Africa - used decompression machines.

Rumor in South African maternity wards was that these women’s children developed extraordinarily fast. This reached the attention of Arthur Jensen, who included it in his pioneering work on prospects for intelligence enhancement:

Heyns has now used the procedure on over 400 women. Their children, when compared with appropriate control groups who have not received the treatment, show more rapid development in the first years of life and manifest overall superiority in tests of perceptual -motor development – tests of the kind that measure infant “intelligence.” The children sit up earlier, walk earlier, talk earlier, and seem generally more precocious than their siblings or other control children whose mothers have not been so treated. We do not yet know if this general superiority persists into later childhood or adulthood, but there is good reason to believe that some substantial overall gain should persist. At two years of age the children in Heyns’s experiment had developmental quotients some 30 points higher

than the control children (with a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15).The explanation for the effects of abdominal decompression on early development, according to Heyns, is that the reduction of intrauterine pressure results in a more optimal blood supply to the fetal brain and also lessens the chances of brain damage during labor. The pressure on the infant’s head is reduced from about 22 pounds to about 8 pounds. The obvious potential importance of this work warrants much further research on the postnatal psychological effects of abdominal decompression.

What happened when these children grew up? Depends who you ask.

If you ask the children themselves, they are definitely unique geniuses - or at least this is the impression I get from decompressionbaby.com, the website where they discuss their experiences. Some typical comments:

I am a decompression baby (born in 1965) and I have very unusual abilities/talents as well as disabilities…I would like to find out whether other babies who were part of the South African study group have similar issues.

I am also a decompression baby. I was born in 1968 and am markedly different from my three siblings who were not decompressed during my mother’s pregnancy with them. My mother tells me that I started acting very differently to my siblings from 2-3 years of age. I do have a higher than average IQ and and am very inventive, but have found it hard to fit in with other ‘normal’ people. I am still unsure if this is a blessing or a curse.

But if you ask scientists, there are no effects.

In 1968, Liddicoat studied 168 babies in a Johannesburg hospital, and found no effect of abdominal decompression on IQ.

In 1974, Griesel studied the visual evoked response (sometimes considered a useful measure of infant intelligence) in 41 decompression babies in Johannesburg and Pretoria, and found no difference from a matched control.

A 2012 Cochrane Review examined these and other studies and concluded there was no role for abdominal decompression in normal pregnancy, although it might be helpful for certain rare conditions associated with elevated abdominal pressure.

These studies seem unanimous, and Cochrane is usually excellent, so I can’t recommend decompression. I do have one tiny remaining note of uncertainty, which is: all of this abdominal decompression research was done in Johannesburg and Pretoria between 1968 and 1974. Elon Musk was born in Pretoria in 1971. I’ve tried to find information on whether or not his mother was a test subject, but come up blank. I assume someone would have mentioned it if she were.

Must be one of those coincidences.

Summary

Here’s a very fast and low-confidence attempt at estimating some numbers - please, I can’t stress this enough , don’t take it too seriously:

“% true” is my personal credence that any given result represents a real phenomenon. Most are lower than 50%. This is intentional - I assume most of this field won’t replicate.

“% relevant” is my totally unfounded guess at what percent of the population any given finding will be relevant for - for example, “don’t eat licorice” is only relevant for people who would otherwise eat a lot of licorice.

“IQ equiv” is how many IQ points this intervention saved in the studies. If it wasn’t measured in IQ points, I tried to figure out how many IQ point loss seemed equally bad compared to whatever it was measuring, which is obviously a total guess. I can’t stress enough how rough these numbers are.

By this very rough estimate, doing everything in this guide would be a gain equivalent to (not of!) ~2 IQ points. I didn’t include embryo selection in the estimate, because that lowers risk of many serious diseases by a lot, and this is both hard to translate into IQ points - and, if translated into IQ points, would probably overwhelm everything else on here, making everything else look kind of irrelevant.

I published the first edition of this guide in 2012, before the replication crisis. I was young and stupid, believed all the studies, and estimated that you would gain the equivalent of 17 IQ points by following a similar package of interventions. Now I’m older, wiser, and more pessimistic. I’m still not at all sure it’s pessimistic enough.