On Cerebralab On Nutt/Carhart-Harris On Serotonin

[epistemic status: extremely speculative]

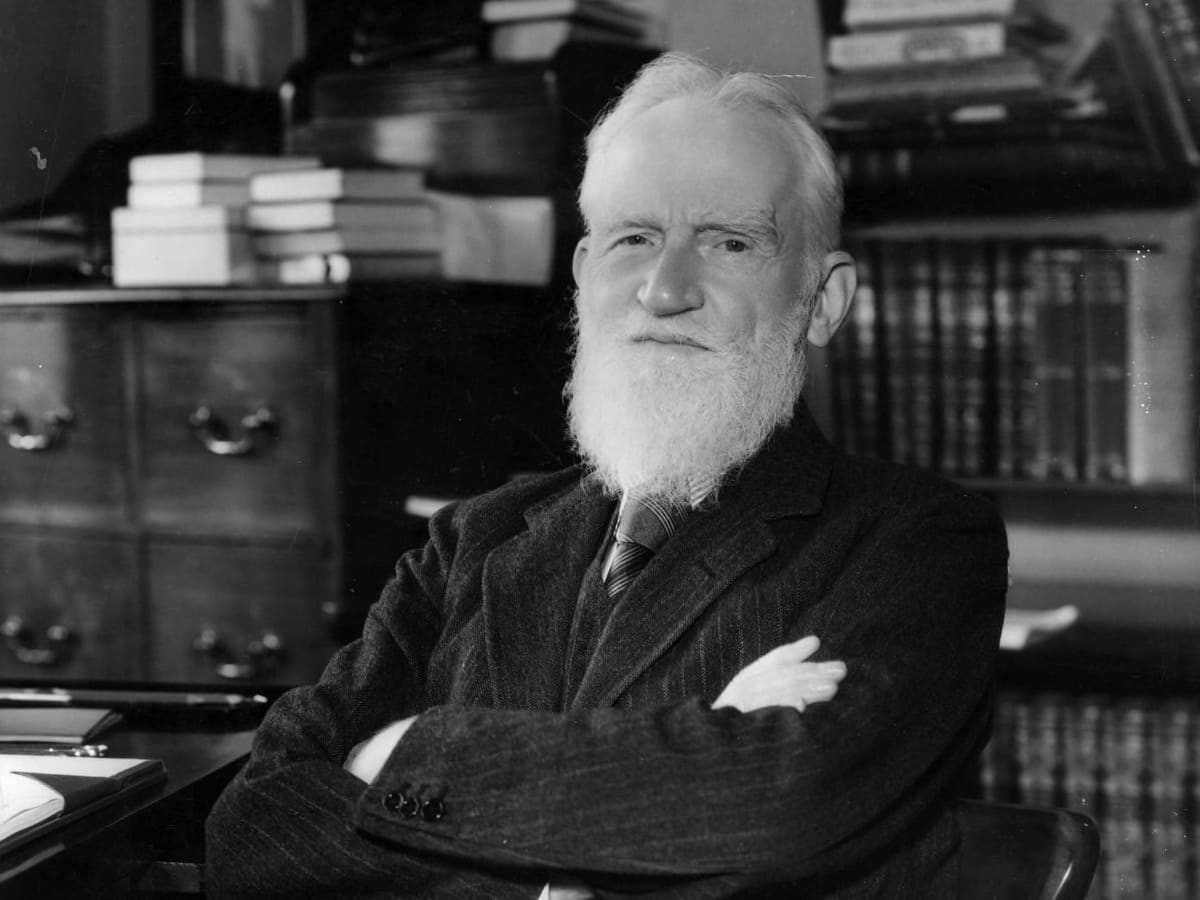

George at CerebraLab has a new review of Nutt and Carhart-Harris’s paper on serotonin receptors (I previously reviewed it here). Two points stood out that I had previously missed:

First of all - predictive coding identifies suffering with prediction error. This conflicts with common sense. Suppose I tell you I’m going to stab you in the arm, you agree that I’m going to stab you in the arm, and then I stab you in the arm, and it hurts a lot. You predicted what would happen correctly, but you still suffered. The theory resolves this with a distinction between common-sense-level and neurological predictions: your brain is “set” to expect normal neurological feedback from your arm, and when it gets pain signals instead, that’s a violated prediction, and this is the level on which prediction error = suffering. But there are other cases where the common-sense and neurological sense of predictions are more congruent. When you first step into a cold shower, you feel suffering, but after you’ve been in it a while you adjust your “predictions” and it’s no longer as unpleasant. If you unexpectedly lost $25,000 it would come as an extremely unpleasant shock, but when you predictably have to pay the taxman $25,000 each year you grumblingly put up with it.

The theory of “active inference” adds another layer of complexity here; it posits that sometimes your brain automatically resolves prediction error through action. If you were expecting to be well-balanced, but actually you’re off-balance, you’ll reflexively right yourself until you’re where you expected to be. At its limit, this theory says that all action takes place through the creation and resolution of prediction errors - I stand up by “predicting” on a neurological level that I will stand up, and then my motor cortex tries to resolve the “error” by making me actually stand.

(one remaining problem here is why and how some prediction errors get interpreted as rewards. If you get $1 million one day because you’re a CEO and it’s payday and that’s how much you make every payday, you will not be especially happy. If you get $1 million because you’re an ordinary middle-class person and a crypto billionaire semi-randomly decides to give you $1 million one day, you will be very happy. This has been traced to reward being dopamine-based prediction error in the nucleus accumbens, and the CEO was predicting his windfall while the gift recipient wasn’t. This suggests there’s still something we don’t understand about prediction error and suffering).

So one question is: for some given prediction error, how much do I suffer vs. adjust my predictions and stop feeling it vs. take action to resolve it?

George’s take on Carhart-Harris & Nutt is that this is influenced by the balance of 5-HT1A vs. 5-HT2A receptors - two different kinds of serotonin receptor. 5-HT1A is (to vastly oversimplify) the main target of antidepressants. The more strongly it’s stimulated, the more likely you are to resolve prediction error by adjusting your predictions - the equivalent of stepping into a freezing shower, but then acclimating so that it feels okay. Suppose you’re depressed/anxious/upset because your boss keeps yelling at you. With enough 5-HT1A activation, you’re better able to - on a neurological level - adjust your world-model to include a prediction that your boss will yell at you. Then when your boss does yell at you, there’s less prediction error and less suffering. This is good insofar as you’re suffering less, but bad insofar as you’ve adjusted to stop caring about a bad thing or thinking of it as something that needs solving - though it’s more complicated than this, since suffering less can make you less depressed and being less depressed can put you in a more solution-oriented frame of mind.

5-HT2A receptors are (to vastly oversimplify) the main target of psychedelics. The more strongly it’s stimulated, the more active your inference gets. George argues that this means psychedelics are more likely to get you to try to solve your problems. But is this really true? The average person on shrooms doesn’t spend their trip contacting HR and reporting their abusive boss, they spend it staring at a flower marveling at how delicate the petals are or something. What problem is this solving? I think Carhart-Harris, Nutt, and maybe George think that this “active coping” isn’t necessarily physical action per se, it’s rejiggering your world model on a deeper level so that it’s more creative and risky in generating strategies. It’s a bias towards thinking of problems as solveable. This could potentially fit with the thing where people who do too much LSD become yogis or transhumanists or whatever; they’re biased towards believing all problems are solveable, even the tough ones like suffering and mortality.

(this mostly, but not completely, meshes with Carhart-Harris’ other work on psychedelics as relaxed beliefs under uncertainty)

All of this was in the paper and my review, but I like the way George ties it together with problems of active inference and the adjusting-predictions vs. changing-the-world tradeoff. If true, this should be testable on the very small scale, with predictions around perception and movement.

[infohazard warning: this next section posits some things that it might be dangerous to think about while on LSD. If you expect to do LSD and obsess over not wanting to think about those things, don’t read further]

The second interesting thing George says is this:

I think for most people it’s pretty obvious why H1A activity can be bad. But why can H2A activity harm? I point back to the diagram above:

- Optimism

- Plasticity

- Sensitivity to stimuli

- Ease of learning

These in of themselves are not things that solve problems, they are things that put you in a problem-solving mindset, looking at the world with fresh eyes, openness, and renewed energy.

This actually seems to reinforce an old bias of mine that people take psychedelics for the wrong reasons, i.e. they take psychedelics to solve “existential” problems that have no real solution other than some form of “accepting”, when instead psychedelics are particularly good for solving a hands-on problem like studying the behaviour of ants, figuring out how your mind works or learning to play an instrument.

I found it curious that people who take psychedelics for introspection usually end up as religious cranks or burnouts. While people that take psychedelics because “they are fun” don’t seem to experience many negative side effects. Under this framework, it makes perfect sense, activate highly conceptual functions in the cortex and tell them to solve an intrinsic and emotional, you’ll end up with some very weird conceptual scaffolding.

I keep wondering how early psychedelicists got so weird - but, equally importantly, how come the 10% of Americans who use psychedelics mostly don’t end out as weird as they did. I’d previously assumed the answer was dosing (though I haven’t done the research into what kind of doses the early pioneers used) or confusion/surprise (since nobody had done LSD before, they didn’t know what to expect and so were more weirded out by the results). But maybe the problem is that the early pioneers were psychologists doing research on themselves, and probably doing a lot of really careful introspection. Maybe these are the people who do worse, and just dropping acid for fun when you go to a dance party is less dangerous than trying to understand your own LSD-addled brain.

Thanks again to George for a new perspective on this interesting paper.