Ontology Of Psychiatric Conditions: Taxometrics

[reposted fromhere, with edits]

I.

Taxometrics is the study of whether psychiatric conditions are categorical or dimensional.

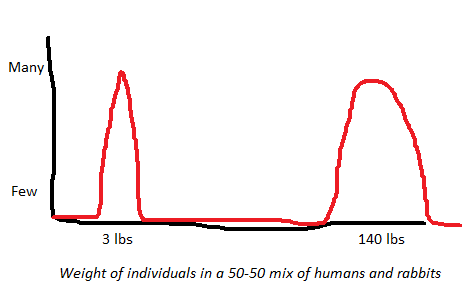

Something is categorical if it neatly, objectively separates into different groups. For example, consider humans and rabbits. If we take a mixed group containing some humans and some rabbits, and graph them along some variable like weight, it would probably look like this:

There’s one big obvious group around 3 lbs (weight of the average rabbit) and another around 140 lbs (weight of the average human). Not a lot of subtletly here. If we used some other graphable variable – height, lifespan, IQ – we’d probably get something similar.

Maybe the biggest rabbit in the world is bigger than the smallest human. That doesn’t mean they’re not two obvious categories. It just means they’re two obvious categories with a tiny overlap. It happens.

If we wanted to be clever, we could create a multivariate distance measure that combines weight, height, lifespan, IQ, and lots of other ways humans and rabbits could differ, into a 0 – 1 variable where 0 is “most rabbity” and 1 is “most humanish”. Probably these scores wouldn’t overlap at all – if they did, it would mean there’s some human who’s more like a rabbit than some rabbit is, which would be pretty surprising. But even if this were true, it wouldn’t change the fundamental finding that humans and rabbits are pretty different. Or to put it some other way, there’s a fundamental hidden generator producing differences between humans and rabbits (in this case, the species difference).

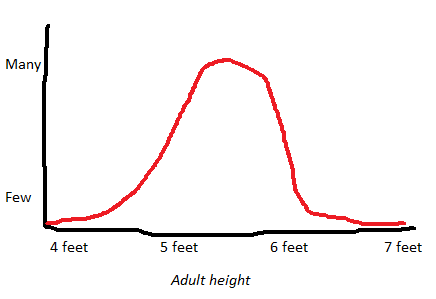

By contrast, something is dimensional if it’s just a spectrum and there’s no obvious place to separate it into different groups. For example, consider tall people vs. short people. We take a general cross-section of the population, and graph them by height, and it would probably look like this:

There’s no clear point where short people stop and tall people begin. Some people are a little taller than others, and other people taller still, and so on until you’re at Yao Ming.

This doesn’t mean “height doesn’t exist” or “height is just a social construct” or anything like that. It doesn’t even mean you can’t talk sensibly about “tall people” vs. “short people”. It just means that Nature doesn’t immediately present you with two distinct categories and a natural cut-off point in between.

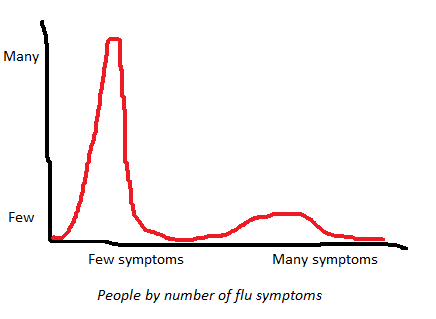

What about well-understood physical diseases? Something like the flu is pretty categorical – either you’re infected with an influenza virus, or you’re not. But suppose we don’t have any high-tech flu tests available. Instead, we must ask people if they have various flu symptoms, score their answers, and sum up the total. We might end up getting something that looks like this (not to scale):

The big peak on the left represents the large majority of people, who don’t have flus. It’s sharp but not infinitely sharp, because some people without flus will still have a few flu symptoms – maybe they have allergies or something. It’s asymmetrical because there are more ways to have more flu symptoms than average than to have fewer flu symptoms than average (especially if the average number of flu symptoms is zero or otherwise very low).

The small hill on the right represents people with the flu. It’s much smaller than the left peak, because people with the flu at any given moment are much less common than healthy people. It’s also much wider, because flu can strike at many different levels of severity, so some flu patients will barely have any more flu symptoms than the average person, and others will be very sick.

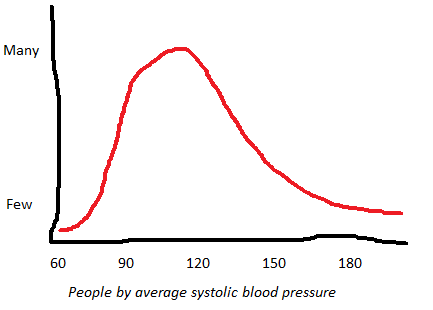

Something like hypertension is more dimensional. A graph of how many people have what blood pressures might look like this:

This doesn’t obviously separate into two groups, “hypertensive” and “non-hypertensive”. We just arbitrarily decide on a cutoff (in the case of hypertension, 130 mm Hg systolic) and call the people above it “hypertensive” and the people below it “not-hypertensive”.

In the flu case, we can ask the additional question “This person has few flu symptoms, but is it possible that’s deceptive and they actually do have the flu?” In the case of hypertension, you cannot ask “This person has a low blood pressure, but is it possible that’s deceptive and they actually have hypertension?” It just doesn’t make sense! In the flu case, we’re using the thing we measure as a proxy for some underlying fundamental difference (whether they’re infected with an influenza virus or not). In the hypertension case, we’re just grading the level of what we’re measuring.

So taxometrics is the study of whether psychiatric disorders work more like the flu, or more like hypertension.

For example, take generalized anxiety disorder. One possibility is that some people have some weird brain quirk called “generalized anxiety disorder” and the rest of us don’t, and we measure anxiety level to try to identify the people with that particular brain quirk. Another possibility is that people just have different anxiety levels, and for some people that anxiety level is so high that it bothers them, and we call that “generalized anxiety disorder”.

If we wanted to determine which one of those was true, we might try giving people a bunch of questions about how anxious they are, then graphing the answers on a plot like the one above. We already have good tests for how anxious people are – things like the GAD-7. So we can just graph GAD-7 scores and then we…

…in fact, this doesn’t work. Let’s look at the flu graph above again.

I admitted above that it wasn’t to scale. If we made it more to scale, it might look like this (seen separately and color-coded on the left, combined on the right):

Because the “has flu” category is so small and so spread-out, it’s actually really hard to notice the tiny secondary bump representing its existence as a separate ontological category. If we tried to just eyeball the distribution of answers on a flu-symptom-questionnaire, we would end up pretty doubtful that the flu was a real thing. Add in the inevitable measurement error, and this just isn’t going to be helpful.

So actual taxometricians use more complicated statistical methods. Theodore Beauchaine describes three of them here, of which I’ll try to very briefly explain one of the simplest, MAXCOV.

Suppose a category is real and involves at least three correlated traits. For example, human vs. rabbit involves weight, lifespan, and IQ; healthy vs. flu involves cough, fever, and muscle pain. Pick one trait – let’s say cough. If the flu is a real category, then as we go from lowest-cough-level to highest-cough-level, the people we’re looking at should gradually go from mostly-not-having-the-flu to 50-50 to mostly-having-the-flu.

In a a group of people who are 100% healthy, 0% flu, fever and muscle pain should correlate at some level. In a group of people who are 0% healthy, 100% flu, fever and muscle pain should correlate at some other level. In a group that’s 50-50, the correlation should be higher than either of these! That’s because level of fever gives you a clue to who has the flu, which in turn gives you a clue about who has muscle pain. In both the 100-0 and 0-100 groups, level of fever doesn’t tell you anything about who has the flu (everyone has the same flu status), so the existence of flu doesn’t give you any useful information. That means that if a categorical difference exists, you should expect the correlation between fever and muscle pain to peak at the level of cough that most effectively divides flu patients from non-flu patients.

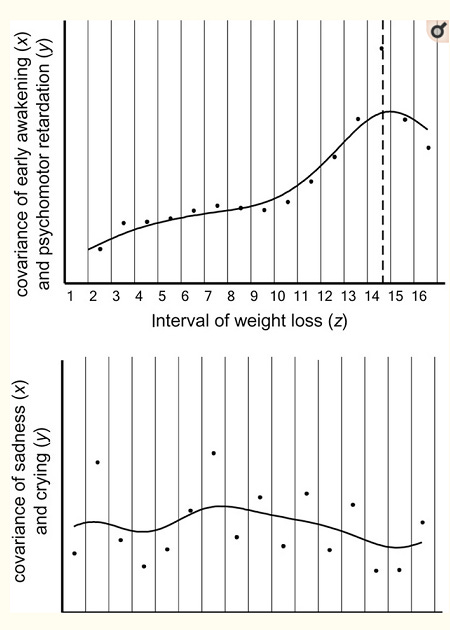

This is Figure 3 from the Beauchaine paper linked above. The first graph depicts an objectively-existing-categorical depression that works like species or influenza. As you increase the level of one depression symptom (unintended weight loss), the correlation between two other depression symptoms (early morning awakening and psychomotor retardation) gradually goes up, peaks at 14, and then starts going down. This suggests that in this case, depression is a real category, like the flu, and the best cutoff to separate depressed from non-depressed people is at 14 of whatever this variable is.

The second graph depicts a dimensional depression that works like height or wealth. As you increase the level of one depression symptom (insomnia), the correlation between other depression symptoms (sadness and crying) stays about the same. This seems a bit off to me – sadness and crying seem like a uniquely bad pair of symptoms to theorize are correlated mostly because of the construct of depression – but whatever, it’s just an example.

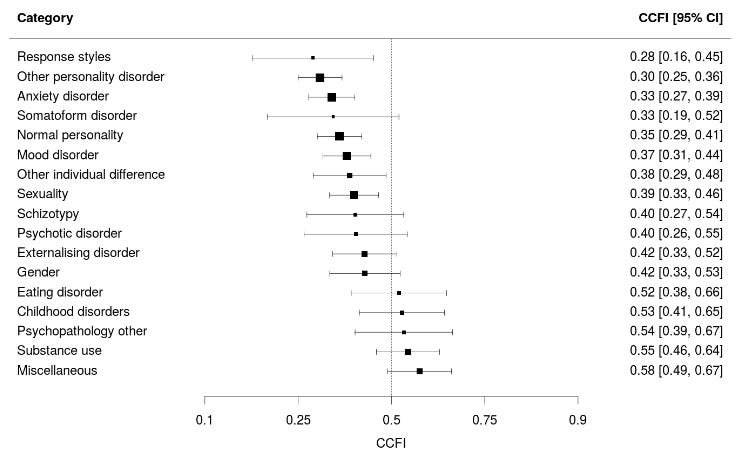

Clear as mud? Don’t worry, this isn’t really what most taxometricians use. They use things that are much more complicated. Any statisticians reading this might enjoy this paper on using the comparison curve fit index in taxometric analyses; no guarantees about anyone else.

II.

In the Brief Taxometrics Primer I’ve been trying to loosely follow in this post, Beauchaine strongly suggests, though doesn’t say outright, that most psychiatric disorders are dimensional, like height and wealth. But a few may be objective distinct categories, especially schizophrenia, narcissistic personality, and endogenous depression (a subtype of depression that happens for no reason, as opposed to the kind of depression you get when something bad happens). This is a completely reasonable set of findings which match my intuition and the intuitions of most other psychiatrists.

But the past two decades of research have treated it poorly. The most up-to-date and comprehensive meta-analysis of taxometric research I can find is Haslam, McGrath, and Kuppens from 2020 . It strongly agrees with (my read of) Beauchaine that most psychiatric conditions are dimensional like height or wealth. It is able to find only hints of exceptions, nothing that it can confidently state is a true category. But its list of exceptions is completely different from Beauchaine’s, and much less sensible. It points to pedophilia, addictions (including gambling addiction!), autism, and intermittent explosive disorder as the most likely candidates for taxonicity (their fancy word for being a true categorical distinction like species or flu).

I’ll grant them pedophilia – it really does seem like people either are or aren’t pedophiles and there’s something weird and specific going on there.

Addictions (they specifically name alcoholism, nicotine addiction, and pathological gambling) are more surprising – doesn’t alcoholism progress pretty gradually from teetotalers to social drinkers to heavy drinkers to raging alcoholics? Doesn’t smoking go from the occasional smoker to pack-a-day smokers to extremely heavy smokers? I haven’t hunted down all their individual studies, but I suspect this is a sort of artifact of how people respond to their addictions. For example, people who have lots of problems with tobacco either successfully quit and become nonsmokers, or don’t quit and become heavy smokers. So there might be an artificial divide where the only people who smoke are the people who do it socially and enjoy it and feel no reason to quit, and the people who are so addicted they can’t possibly quit.

Autism is such an annoying thing to have on this list – just when everyone finally agreed there was an “autism spectrum” and no clear difference between neurotypical-people-with-some-autistic-traits and high-functioning-autistics, along comes this meta-analysis to say nope, it’s a taxon, neurotypicals and autistics are two clear objectively separate categories. I did hunt down the studies here and they actually seemed pretty good. But none of these results are strong enough to be more than suggestive, so I am going to keep believing in an autism spectrum until more research comes in.

And intermittent explosive disorder! This is the fake disorder we made up so that we had something to diagnose angry people with! I don’t think anyone thought this one was real, not even the psychiatrists who invented it and stuck it in the DSM! But here come the taxometricians, saying that schizophrenia and bipolar and whatever are mere dimensional variation, but IED (yes, that’s really the acronym) is an honest-to-goodness crisply-defined category based on objective reality? What gives?

And look what isn’t on here – schizophrenia, which is just a really obvious separate taxon. You know, the condition where sometimes between ages 18 and 25 for men and ages 25 to 35 or so for women, over the course of a few weeks, seemingly normal people start getting extreme hallucinations and eventually devolve into a state where they often can’t live a normal life or even speak meaningful sentences? The taxometricians are saying ah, whatever, it happens to all of us, they’re just the people who it happens to more than average? Is that really what they’re saying? I think they may have bungled this one, maybe by over-focusing on studies of negative symptoms, or of psychosis more generally, but I haven’t looked into it enough to be sure.

Overall this is just a really enraging meta-analysis, and even though their methods look good and they did a lot of work to double-check their results, I have trouble trusting them. To their credit, they are pretty careful about what claims they make, and only say that the data is suggestive of most of their categoricity claims.

Maybe instead of focusing on these few tenuous exceptions, we should focus on the headline result: 75% of findings were “unambiguously non-taxonic”, 17% were “unambiguously taxonic”, and 8% were “ambiguous”. In other words, the field as a whole pretty strongly suggests that most psychiatric disorders are just the tail end of normal variation, like “tall person” or “rich person”, and not a separate category like “rabbit” or “has the flu”. Among the conditions that were very strongly found to be dimensional only were depression, anxiety, and ADHD.

In more depth:

This is a forest plot of CCFI, the more complicated taxometry statistic I linked before. CCFI below 0.5 suggests dimensional variation like height or wealth; above 0.5 suggests true categories like species or having-the-flu. This plot is using much broader categories than the individual conditions I mentioned before, but we can see that eating disorders (like anorexia), childhood disorders (like autism), substance use (like alcoholism), and a bunch of grab bag categories (including things like dementia) are most likely to look taxonic.

A few other things stand out here. Just for fun, the authors included some normal personality traits and psychological variables, like “religious fundamentalism” and “interest in science”. I think (though they don’t say so explicitly) that Big Five traits like extraversion and so on are also in there. They predictably find low CCFI for these, meaning they’re just dimensional normal variation. These are honestly around the same CCFI as anxiety and mood disorders, meaning that “depression” behaves in as trait-like a way as “interest in science”, and vice versa. If you weren’t planning on coming up with some separate category of “science-lovers” and demanding everyone classify themselves as in it or out of it, you probably shouldn’t do the same with depression.

They also have a category called “gender”. They say they included measures like “femininity” and “sex-stereotyped activities” in there – I can’t find more specifics. It has a CCFI of 0.42 with confidence interval including 0.5, so looks slightly more dimensional, but can’t quite rule out it being slightly more categorical. If anyone ever demands you have an opinion on the question “is binary gender real?”, I think the most scientifically-supported answer would be “it has a Comparative Curve Fit Index of 0.42 plus or minus 0.1, which means it trends towards dimensionality but taxonicity cannot be ruled out”. There’s also a “sexuality” category on here, but it’s such a grab bag of different things (sexual orientation, how promiscuous you are, etc) that I’m not sure you can get much out of it; look at the individual studies if you want to know more.

III.

Does this mean that, contra all those public awareness campaigns, “depression is just normal sadness” or whatever?

I’m not sure clinical depression is even kind of the same sort of thing as sadness. Lots of aspects of depression - like its tendency to occur in episodes lasting on average six months to a year - don’t seem like jacked-up aspects of normal sadness. So maybe this a bad example. But we can probably come up with equally awkward questions about other conditions. Is Generalized Anxiety Disorder just normal anxiety? Is ADHD just normal absent-mindedness?

Not necessarily normal. As the old saying goes, quantity has a quality all its own. Just because something is on a continuum with something else, doesn’t mean it has to be close to it.

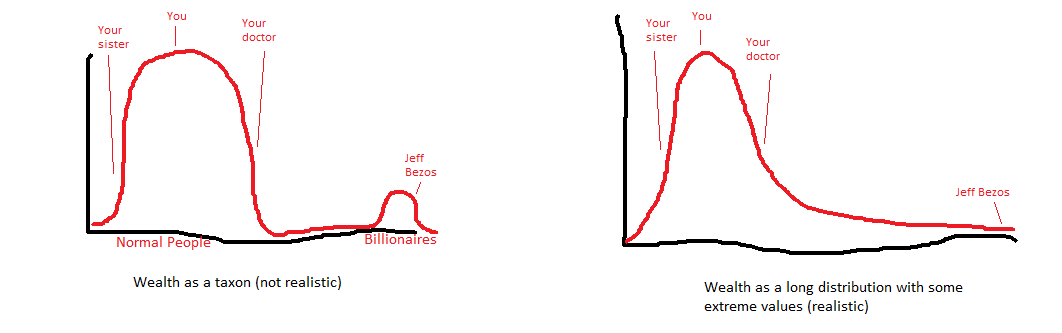

Suppose you make the US median income of $36,000/year. You live in an average American town where you see people of various social strata. Your doctor makes $200,000/year and drives a Tesla. Your sister is a single mother making $20,000/year, and needs food stamps to make ends meet. You probably think you have a good sense of class distinctions.

What about Jeff Bezos? Is Bezos’ fortune “just normal wealth”?

Taxometrically: yes. Jeff Bezos falls on the same continuum as everyone else. You can add one dollar to your own net worth, and keep doing that, and eventually end up at Jeff Bezos’ net worth. At every point in between - a few hundred thousand, a few million, a few tens of millions - there will be some people at that point. There’s no clear distinction into two disjoint groups, where you’re in one and Jeff Bezos is in the other.

Practically: no. Practically , Jeff Bezos might as well be a different species. If your idea of wealth is a doctor who makes $200,000 a year, you’re totally unprepared to think about Jeff Bezos. Your whole economic world between the poor single mother and the rich doctor occupies one order of magnitude; Jeff Bezos is five orders of magnitude beyond it.

In Nassim Taleb’s language, Jeff Bezos lives in Extremistan. If you’re expecting a normal distribution, Bezos is way outside of it and looks like a different species. But really he’s just at the tail end of a distribution with much longer tails than you expected.

If this is true, I think it’s fair to think of severe ADHD as having the same relationship to normal absent-mindedness that Jeff Bezos has a to a guy making a little above median income. They’re the same sort of thing on the same distribution. But one is so much further out than our normal vocabulary for talking about these kinds of differences that it’s okay to have a different word for it and different intuitions around it.

IV.

If most mental disorders are dimensional variation rather than taxa, that kind of makes the DSM look pretty silly, doesn’t it?

Remember, the DSM is fundamentally a diagnostic guide. It’s a list of criteria to determine who has eg depression. To oversimplify just a little, if a patient has five or more of their depression criteria, then they “really have” depression, and a psychiatrist should diagnose them. If they only meet four or fewer, they don’t have depression, and should not get the diagnosis. All of this is predicated on the idea that there’s a specific thing called depression that you either do or don’t have.

Dimensional variation doesn’t work that way. Let’s return to our wealth analogy. Imagine a manual which let you diagnose someone as “rich” only if they meet at least three of the following criteria:

1. Owns five or more cars

2. Has a house in a gated community

3. Has an income of $1,000,000 a year or above

4. Takes first-class flights at least three times a year

5. Engages in rich-person activities (horseback-riding, golfing, reading the New Yorker) at least twice a month

…and then every few years economists get into huge fights about whether maybe we should change this and say you have to own six or more cars, or whether there should be an exemption for people who own fewer cars but do have a private jet, and they all take it really really seriously.

The problem isn’t that the criteria are wrong. All of these are perfectly reasonable characteristics to correlate with richness. The problem is that your project of dividing the world into “rich” and “not rich” is fundamentally not a scientific one, and is more likely to confuse than to enlighten. Someone with an income of $999,999 isn’t interestingly different from someone with an income of $1,000,001; owning four cars blends seamlessly into owning five.

This isn’t to say you never want to do something like this. Suppose Bernie Sanders wants to increase taxes on the rich, but not on everyone else. He needs some regulation about who the increased taxes hit, and maybe something like this checklist (or more realistically just the income cutoff at $1,000,000) is the way to go. It’s fine if he wants to set something up like that – as long as economists don’t look at his division of people into two bins and mistake it for the discovery of an underlying cosmic secret that there are two types of people, rich and non-rich, separated by the $1,000,000-a-year mark.

Are psychiatrists mistaking moderately useful bins for underlying cosmic secrets? It’s hard for me to tell exactly how many people make this mistake; the people who understand what’s going on and are just using the categories as rules-of-thumb tend to sound a lot like the people who don’t. My guess is most professionals, and an overwhelming majority of laymen, are actually confused on this point, and this messes them up in a lot of ways.

An economist or sociologist looking for the causes of wealth or poverty understands that they’re doing a pretty complicated thing. In the complex system that is human economic behavior, they will probably find that all sorts of factors like upbringing, education, genetics, health, discrimination, and luck interact to determine how much money you have. On the other hand, a microbiologist looking for the cause of the flu will be hoping to find a single specific thing – one virus that all flu patients have and all healthy people don’t. I think a lot of people still want psychiatry to deliver the single specific thing. It’s not going to be able to do that. If you hold out hope, you’ll either end up overmedicalizing everything, or you’ll get disillusioned and radicalized and start saying all psychiatry is fake. I think either would be a mistake.

In my practice, I’ve moved away from asking questions like “does this patient really have ADHD”? Those kinds of questions make me feel like I’m trying to decode their symptoms to uncover some secret variable that could be either 0 or 1. But there is no such variable. Instead, I ask “how much trouble does this person have with paying attention?”. This is usually pretty easy to figure out; the patient will just tell me if I ask!

Likewise, I’ve moved away from thought processes like “If this person has ADHD, they genuinely need a stimulant; if not, they’re just faking”. Instead, I try to think of how much the patient’s symptoms are disabling them, whether a stimulant would relieve some of those symptoms, how likely the symptoms are to go away without an stimulant, and, based on all this, whether the benefits of a stimulant outweigh the risks.

(this has another implication: stimulants shouldn’t be thought of as magic bullets that “cure” “ADHD” by fixing the underlying cause, in the same way that Tamiflu cures the flu by blocking flu viruses. They should be thought of as things that affect the underlying stew of variables that cause ADHD in some helpful way. By comparison, giving someone a college scholarship might help them become richer, but it’s not “curing” “the” “cause” of “poverty” in a way that flips them from a “not rich” to a “rich” status.)

Also, this is why I don’t like the pressure to use person-centered-language (eg instead of “autistic person”, you should say “person with autism”). This sends exactly the wrong signal. If autism is dimensional, we should think of it the same way we do height and wealth – and we say “tall person” and “rich person”. Saying “person with Height” or “Person with Richness” is strongly suggestive of “person with the flu” – it implies a binary class that you either fall into, or don’t. But that’s the opposite of what most research suggests, and the opposite of the thought process that will help you think about these conditions sensibly.