Pascalian Medicine

I.

When I reviewed Vitamin D, I said I was about 75% sure it didn’t work against COVID. When I reviewed ivermectin, I said I was about 90% sure.

Another way of looking at this is that I must think there’s a 25% chance Vitamin D works, and a 10% chance ivermectin does. Both substances are generally safe with few side effects. So (as many commenters brought up) there’s a Pascal’s Wager like argument that someone with COVID should take both. The downside is some mild inconvenience and cost (both drugs together probably cost $20 for a week-long course). The upside is a well-below-50% but still pretty substantial probability that they could save my life.

(Alexandros Marinos has also been thinking about this, and calls it Omura’s Wager)

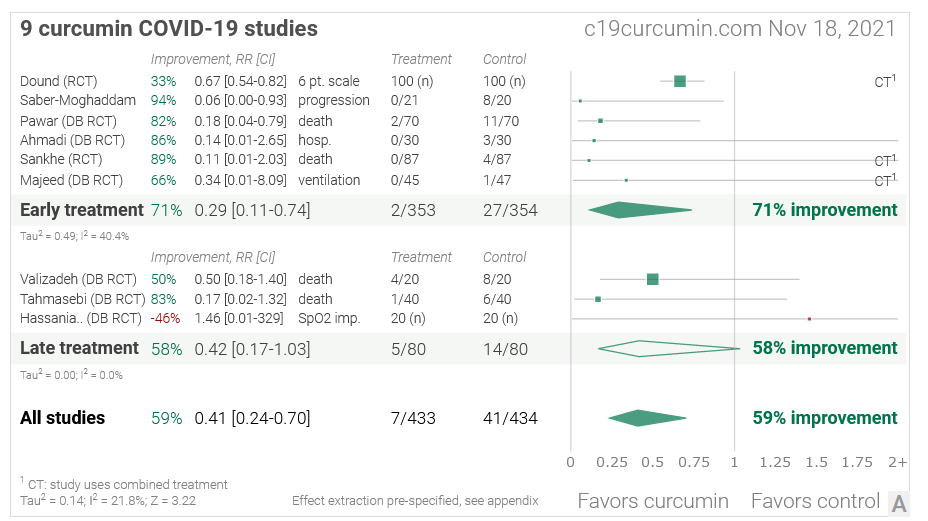

We can go further. The same people behind ivmmeta.com have posted this “meta-analysis” of curcumin, a common spice and oft-mooted panacea:

(source)

(source)

I’m going to guess it’s not true, because I’ve become pretty critical of these people’s methodology since doing the ivermectin review. Also, curcumin is a PAIN (pan-assay interference compound, ie a substance with weird chemical properties that make every test seem positive, so if you do chemical tests to see whether it activates eg coronavirus-fighting immune cells, it will always say yes). This means people are always publishing exciting papers about it and alternative medicine people are always getting really enthusiastic about it and suggesting it as the cure for everything (eg depression).

Still, I don’t have enough time and energy to review this evidence base thoroughly. And here I am, being told that nine studies found highly positive effects. With nine studies finding highly positive effects in favor, and just my vague ungrounded skepticism against - and given that people’s naive probability estimates are usually overconfident - can I really say that I’m 95% sure this doesn’t work? And if I’m not 95% sure this doesn’t work, doesn’t that mean there’s a 5% chance it does work? And since a course of curcumin costs about $10 and is harmless, if there’s a 5% chance that it thing reduces COVID mortality by 70%, shouldn’t I use it? In fact, shouldn’t I be working as hard as I can to make every hospital, doctor, and patient in the world use it?

But what’s true of curcumin is equally true of lots of other different compounds: zinc, hydroxychloroquine, quercetin, nigella sativa, melatonin…just going off the ones on the sidebar of ivmmeta.com, there are about thirty different things that have this same level of very early, very dubious super-promising COVID results. Some are expensive and some are dangerous, but I think about twenty of them are cheap and safe.

The establishment medical position is that you shouldn’t take any of these, because they haven’t been proven to work. The Insanity Wolf position is: maybe you should take all twenty, because you won’t have lost very much, and if even one of them works, it’s worth it.

In fact, Insanity Wolf has a strong argument here: one chemical in this class is fluvoxamine. Six months ago, it was just like all these others: something with a clever story of why it might work and a few weak preliminary studies, but only the sort that never pan out in real life. Then a really big, excellent randomized trial seemed to find it worked, and the current scientific consensus agrees this is probably true. So if you’d done the Insanity Wolf thing six months ago and taken twenty untested compounds, at least one of them would have worked and cut your COVID mortality by 30% (our current guess at fluvoxamine’s effect size).

But why stop there? Sure, take twenty untested chemicals for COVID. But there are almost as many poorly-tested supplements that purport to treat depression. The cold! The flu! Diabetes! Some of these have known side effects, but others are about as safe as we can ever prove anything to be. Maybe we should be taking twenty untested supplements for every condition!

II.

So what’s the counterargument?

Is anything ever truly safe? There’s a species of parasitic worm called Loa loa. Usually it hides from the immune system. But if you take ivermectin for some unrelated reason, the loa loa dies en masse , the immune system notices the corpses, it freaks out and massively overreacts, and sometimes your brain gets fried in the crossfire. If you get this, kudos - it’s one of the most esoteric ways to die, and any medical professionals in the vicinity will be impressed. But my point is, “this drug has no side effects” is a fraught statement. In principle ivermectin is perfectly safe; in practice, the world is full of weird stuff that can make harmless drugs kill you unexpectedly.

And: sometimes people give older people ivermectin to treat scabies. A few decades ago, a study suggested this increased mortality pretty significantly, suggesting that ivermectin is dangerous in the elderly. IIRC later studies couldn’t replicate this, and I think the current consensus is that it’s fine. But if we’re talking about “maybe our interpretation of the studies is wrong” and “but there’s still a small chance”, we’ve got to apply this on the negative side as well as the positive.

But I have to admit that given everything I know about ivermectin - and Vitamin D, melatonin, etc - I still think on net the very small chance that this stuff helps you is higher than the extremely small chance it kills you. Even if the latter isn’t quite zero.

What about unknown unknowns? This is a two-way street: these chemicals might have unexpected risks, but also unexpected benefits. Vitamin D can contribute to kidney stones in vulnerable individuals, but it also helps bone health, and there are various (probably false) claims that it prevents cancer, helps depression, etc. But as a corollary of Algernon’s Law (your body is already mostly optimal, so adding more things is unlikely to have large positive effects unless there’s some really good reason), probably we’re more likely to discover unexpected risks than unexpected benefits.

Still, varying the value of the “unknown unknowns” term until it says whatever justifies our pre-existing intuitions is the coward’s way out. We don’t fret over the unknown unknowns of Benadryl or Tylenol or whatever, even though we know their benefits are minor. Ivermectin, Vitamin D, etc are well-studied chemicals, and even though there’s always some chance everything is bad, at some point that chance becomes low and we can still say that on net the benefits outweigh the risks.

Should we worry that even if each drug individually is net positive, giving someone twenty medications will lead to some crazy interaction? I’m not too concerned about this; clinically significant drug interactions are rarer than most laypeople think, and usually pretty predictable. Still, giving twenty different medications at once is almost unexplored territory, and something like this might be true.

(but if it is, maybe it’s an argument for just giving the one or two most promising unlikely treatments, instead of all twenty)

Even if Pascalian medicine is an individually reasonable choice, might it be bad at the level of society? No individual drug or supplement we’ve talked about so far costs very much money. But giving twenty inexpensive things to everyone with every disease quickly becomes expensive. On the other hand, the US medical system gave up on caring about costs long ago, and it’s not clear this would cost any more than eg Aduhelm or several other bad decisions we’ve already made.

Maybe more important: patients already don’t take about a quarter of the drugs they’re prescribed. People on the Internet demanding that new drugs be made available are a pretty unrepresentative sample of normal humans, who generally hate medications and will not take them even when doctors say it is very important. These people will never take twenty different pills (and combining these into a 20-way combination pill would be tough for many practical and legal reasons). If you ask them to do this, they will just take none of them, including the one pill that we know works and is very important.

If it became generally accepted to prescribe lots of pills that probably didn’t work, and patients knew this, it might decrease trust in all medications. Even if your doctor said “this is one of the ones that definitely works”, some people wouldn’t believe them. And there’s no bright line between the ones that have a 99.9% chance of working, 99% chance of working, 90% chance, 50% chance, and 5% chance (which are antidepressants? I would say closest to 90% chance of working in theory, 50% for an individual patient - but I’m not sure!) This could water down patient perception of every medication from “effective cure” to “shot in the dark”.

Still, if this is true, you might conclude that it just means doctors shouldn’t universally recommend Pascalian medicine. It could still be rational to set up a course of it on your own.

I think this would be equally fraught. If doctors are setting this up, you can at least be confident that they’re picking the medications that actually have very few side effects. If you’re doing it on your own, you’d better hope you’re good at doing your own research - better than all the people who did their own research during COVID and concluded all sorts of totally false things. At the very least, you’d have to add a term for “this actually has lots of well-known side effects but I am missing them”.

There’s a potential compromise solution, where smart doctors come up with Pascalian medicine protocols for the few patients who would actually want them. But this would be a weird enough thing for a doctor to do that it would run into the “I wouldn’t trust any club that would accept me as a member” problem.

III.

Here’s the counterargument that bothers me the most:

I think ivermectin doesn’t work. I think that it looks like it works, because it has lots of positive studies and a few big-name endorsements. But our current scientific method is so weak and error-prone that any chemical which gets raised to researchers’ attentions and studied in depth will get approximately this amount of positive results and buzz. Look through the thirty different chemicals featured on the sidebar of the ivmmeta site if you don’t believe me.

So if you’re an onion farmer, and you have a bunch of extra onions you can’t sell one year, all you have to do is ask some scientist friends to study whether onions cure cancer. There will be a bunch of studies, lots of them will be sloppy and say yes, people like me will see a bunch of positive studies and say “Can I really be more than 99% sure this is false? and if there’s even a 1% chance onions cure cancer, then - given how safe they are - isn’t it worth trying?” And then doctors will make every cancer patient take concentrated onion extract every day. Then eggplant farmers will want in on the money-printing-license, and then pumpkin farmers, and soon we’re up to 100 pills a day instead of just twenty. And then we’ll wish we’d stopped Pascal’s Wager-ing drug decisions at some earlier point. And maybe the right point to stop is now.

I’m nervous about this scenario because it violates the Law Of Conservation Of Expected Evidence - if I “know” that onion farmers doing studies will convince me that onions have a 5% chance of curing cancer, I should just believe there’s a 5% chance onions cure cancer now. So I must be doing something wrong here. Probably what I’m doing wrong here is saying that ivermectin having some decent studies raises its probability of working to 5%. I should just say 0.1% or 0.01% or whatever my prior on a randomly-selected medication treating a randomly-selected disease is (higher than you’d think, based on the argument from antibiotics).

From the Outside View, this argument seems strong. From the Inside View, I have a lot of trouble looking at a bunch of studies apparently supporting a thing, and no contrary evidence against the thing besides my own skepticism, and saying there’s a less than 1% chance that thing is true.

But as long as I can’t make that leap, I can be money-pumped by onion farmers. Reconciling Inside And Outside Views Remains Hard, More At 11.

IV.

Does Pascalian medicine beat our current strategy of only using drugs that are proven to work? I don’t know. I think the current strategy makes sense on a social level, but I’m not sure that the Pascalian strategy wouldn’t work for an individual. At least an individual who is able to reliably identify which low-but-nonzero-probability-of-benefit drugs really do have very few potential side effects (if you didn’t already know about loa loa encephalopathy, consider that this might not be you; I am very much not-recommending that any reader here do this on their own).

I know of only one person who takes the Pascalian argument completely seriously. Futurist Ray Kurzweil used to take 250 different supplements every day - but after realizing this was excessive, cut it down to only 100. I would love to hear from him, or anyone else who does this - but I assume he’s too busy taking pills to comment.