Peer Review Request: Depression

I’m trying to build up a database of mental health resources on my other website, Lorien Psychiatry. Every time I post something, people here have made good comments, so I want to try using you all as peer review.

This is a rough draft of my page on depression. I’m interested in any feedback you can give, including:

1. Typos

2. Places where you disagree with my recommendations / assessment of the evidence

3. Extra things you think I should add

4. Your personal stories about what things have or haven’t helped, or any extra insight that your experience with depression has given you

5. Comments on the organization of the piece. I don’t know how to balance wanting this to be accessible and easy-to-read with having it be thorough and convincing. Right now I’ve gone for a kind of FAQ format where you can only read the parts you want, but I’m doubtful about this choice.

6. Comments on the level of scientific formality. I tried to get somewhere in between “so evidence-based that I won’t admit parachutes prevent injury without an RCT” and “here’s some random stuff that came to me in a dream”, and signal which part was which, but tell me if I fell too far to one side or the other.

Ignore the minor formatting issues inevitable in trying to copy-paste things into Substack, including the headings being too small and the spacing between words and before paragraphs being weird. In the real page, the table of contents will link to the subsections; I don’t know how to do that here so it might be harder to read.

Here’s the page:

Depression

The short version: Depression has a combination of biological, psychological, and social causes. You can address the social causes by changing your life circumstances (and research suggests people underestimate the potential benefits of making major life changes). You can address the psychological causes with therapy; possible therapies are diverse and complicated but I especially recommend “behavioral activation” therapy (where you try to keep a schedule and also do new, interesting things) and David Burns’ book Feeling Good. You can address the biological causes with a combination of lifestyle changes, medications, and supplements. Consider exercising more and adapting a modified Mediterranean diet. Consider taking antidepressants like escitalopram and bupropion, and supplements like l-methylfolate. Other non-chemical biological options include light therapy (safe and easy), transcranial magnetic stimulation (more complicated), and electroconvulsive therapy (difficult but extremely effective last-ditch solution). If something treats your depression, continue it for some length of time depending on the type of intervention, then consider withdrawing it to see if you can maintain your mood without it.

The long version:

1. What is depression?

1.1: Is depression caused by biochemistry or life events?

1.2. How can I tell if I have depression?

1.2.1. How do I know if I have depression vs. something else?

2. How do you treat depression?

2.1. What kind of lifestyle changes help with depression?

2.1.1: What do you mean by getting away from the depressing thing?

2.1.2: What kind of diet helps with depression?

2.1.2.1: What if I have special dietary needs (vegetarian/vegan/paleo/gluten-free/etc)?

2.1.3: What kind of exercise helps with depression?

2.1.4: What’s the role of sunlight in treating depression?

2.1.5: What’s the role of hygiene, routine, and behavioral activation in treating depression?

2.2. What kind of therapies help with depression?

2.2.1. How can I get a therapist?

2.2.2. How can I get therapy without a therapist?

2.3. What kind of medications help with depression?

2.4. What kind of supplements help with depression?

2.5. What else treats depression?

2.6. What should I try to treat my depression?

2.7. If something helps treat my depression, how long do I have to do it for?

1. What is depression?

Depression is a condition marked by low mood, low motivation, persistent negative self-talk, and countless similar and related issues.

Although it’s fair to call it a “mental illness” as a heuristic, it isn’t “just” “in your head”. Severe depression sometimes affects the psychomotor system as well, producing unusually slow movements and decreased muscle strength. Some depressed people feel like their limbs “have lead weights tied to them”, and this feeling is “real” – it’s the extra work it takes to maintain a posture despite decreased ability to exert muscle force. It’s linked to decreased efficiency in almost every part of the body, including the immune system, the cardiovascular system, and (especially) the gastrointestinal system. Chronically depressed people live almost a decade less than non-depressed people, and there’s increasing evidence that this isn’t just because they’re too depressed to eat right and exercise, it’s also because the same neurological processes affecting their emotional system are affecting the nerves that regulate the heart, lungs, stomach, etc. The emotional / psychological symptoms of depression are so striking that they trick us into thinking depression is “just” an emotion – but even if you could eliminate every emotional symptom tomorrow, depression would still be a serious disease of dysregulated bodily systems.

We don’t understand exactly what depression is, but we have clues about how it works on a neurological, biochemical, and cognitive levels. The following is extremely speculative but (I think) the best picture we can draw from the evidence so far.

On the neurological level, one line of research suggests depression involves neurons forming fewer synapses, especially in the hippocampus region of the brain. Remember, neurons are the type of brain cells which carry thoughts and information; each cell sends its information to thousands or millions of other cells through branching wires called synapses. A healthy brain carefully regulates the number and strength of synapses, which lets you maintain what feels like a normal train of thought – each idea leads to other ideas; unmet needs lead to desires, plans, and goals; urges lead to movements; et cetera. The depressed brain forms fewer and weaker synapses than usual. Each thought or need or urge is a stone thrown into a deep lake, producing no ripples. Communication between brain areas becomes weak and muffled. This is true for the very basic brain areas that (for example) regulate stomach contraction as much as for the very advanced brain areas that regulate your emotion, which is why sadness and stomach problems are both depression symptoms.

On the biochemical level, depression seems to often involve shortages of a chemical called BDNF – brain-derived neurotrophic factor. A neurotrophic factor, or nerve growth factor, tells neurons to form more synapses; if depression is related to decreased synapse number, it makes sense that this chemical would be missing. Unfortunately, BDNF is a complicated and unstable molecule, and there’s no easy way to get it into your brain except by drilling a hole in your skull and injecting it directly – something which cures depression reliably when scientists do it to rats. Since we don’t want to do that to most patients, we’re reduced to fiddling with other chemicals that seem to be upstream of BDNF or able to increase its production – one of which is serotonin.

On the cognitive level, depression is a global prior on negative stimuli. A prior is like an assumption, bias, or context, in the sense “you have to take that in context”. Your brain is constantly applying priors to all its perceptions to try to wring as much extra meaning out of them as possible – you can see some examples here. A global prior on negative stimuli means that the brain interprets everything it sees in the context of an assumption that it’s probably bad. A depressed person who goes on a date is likely to focus on all the worst and most embarrassing things they said, all the subtle signs that the other person didn’t like them, and then conclude that they’re forever unloveable (when a healthy person might have thought it went perfectly fine). But it’s broader than this: a depressed person will systematically overlook good things and hyperscrutinize bad things in every area of their lives. Every psychotherapist is familiar with patients who have high-paying prestigious socially-useful jobs, happy families, are beloved by everyone in their community – and who sit down on the couch and say “I guess I’m a total failure, I haven’t accomplished anything with my life and nobody likes me”. If you bring up any of the many positive things about them, they’ll come up with arguments for why those don’t count. This produces the flashy emotional and psychological symptoms of depression, but it’s deeper than this – depressed people are worse at simple sensory processing tasks involving happy faces.

I don’t understand why the neurological problems with synapse formation and the chemical problem with BDNF levels cause the cognitive problem with a negative prior. It seems like this is inconsistent among depressed people; some report feeling intense negative emotions, but others report feeling no emotions at all. Still, the negativity is a pretty classic symptom, and the first one a lot of people notice.

I am very non-confident about all the specifics of this model, but very confident in the underlying point that depression is a complicated neurological disease that happens to have some easy-to-notice emotional symptoms, and not just another word for feeling negative emotions.

1.1: Is depression caused by biochemistry or life events?

Either is possible, and most often it’s both.

I know patients whose depression is clearly based on life events – for example, one person who consistently gets depressed every time she breaks up with a partner. I know other patients whose depression strikes seemingly at random, when everything in their life is going fine. Still other patients get depressed based on a specific trigger, like the time of year.

Along with the neurological, biochemical, and cognitive levels mentioned above, there’s a fourth level on which you can try to understand depression – a mathematical level. On the mathematical level, depression is an attractor state in a dynamical system. It looks like that dynamical system takes both life events and biochemical factors as inputs, and based on the different weights of the edges of the graph in different people (probably at least partly genetically determined), either or both of those can shift it into the new depressed attractor state.

How do life events interact with biochemistry? One oft-studied route is the stress hormone cortisol, which very clearly interferes with synaptic growth and is probably a key link between the neurological, biochemical, and life-history aspects of depression. Another is “overlearning”: the brain tries to learn from events – if you lose every baseball game you play, eventually it will figure out you’re not very good at baseball (ie develop a negative prior on baseball skill). But in some situations it can “overlearn” – for example, if you lose one baseball game, conclude that you’re no good at anything and never will be. If some factors (maybe neurological or biochemical) make negative overlearning more likely, potentially a major negative event could shift you into a strong global negative prior.

If you have a really good reason to be sad, does that mean you’re not depressed? Different authorities differ, but the most recent DSM says that as long as you have a full set of depression symptoms, you qualify for a depression diagnosis, no matter how awful your life is. Antidepressants will treat good-reason-based depression as effectively as they treat any other kind of depression.

1.2. How can I tell if I have depression?

The traditional nine symptoms of depression are:

1a. Low mood (could be that you feel sad all the time, but could also be that you don’t feel anything at all)

1b. Anhedonia (it’s hard to feel pleasure even when doing things that used to be pleasurable)

2. Sleep problems (could be anything from having unusual trouble falling asleep, to waking up too early, to sleeping too long)

3. Loss of interest in activities (you no longer enjoy pasttimes/hobbies you used to find fun)

4. Guilt (or rumination about how bad you are, or low self-esteem, or excessive anxiety that you’re failing people / letting them down)

5. Lack of energy (you can’t get out of bed, you can’t make yourself work hard or pursue goals)

6. Concentration problems

7. Appetite problems (could be either that you’ve lost all appetite, or that you eat more than normal – especially common with junk food)

8. Psychomotor retardation (you move more slowly than normal – kind of a rare symptom and hard to notice, don’t worry if you don’t have it)

9. Suicidal thoughts

The DSM-5 says you qualify for a diagnosis of depression if you have 1a/1b and any other four of these symptoms. Realistically, most people know if they’re depressed or not and don’t need to go through a checklist to figure it out. On the other hand, if you really like going through checklists to figure out if you’re depressed, you can take the HAM-D, a very official depression test used in studies, and it will tell you exactly how depressed you are.

1.2.1. How do I know if I have depression vs. something else?

I think it’s barely worth clearing up confusion between depression and anxiety. About half of people with either depression or anxiety will also have the other. They seem to be closely related psychological processes, and most of the treatments for one will also treat the other. If you’re worrying about whether you have more depression or more anxiety, please stop worrying about this and get your depression-anxiety treated. OCD and panic disorder are also in this cluster of things.

Trauma and PTSD can cause depression, and it can be mildly helpful to work on the depression directly, but it’s probably more helpful to work on the trauma. If you suspect that your depression is related to stress over a trauma you’re having trouble processing, I would recommend worrying about the depression only long enough to make sure you’re stable, and otherwise putting your effort into pursuing therapy for trauma.

Some illnesses cause depression as a side effect. The most typical are thyroid deficiency and anemia. Signs of thyroid deficiency include feeling cold all the time, cold dry skin, gaining weight very easily, constipation, and muscle cramps. Signs of anemia include being very pale, very tired, and being in some demographic with high anemia risk (for example, vegetarians with iron deficiency or women with heavy periods). A few people with anemia also feel compelled to eat weird things like dirt or ice. If you have some of these symptoms, mention them to your doctor, who can do a simple blood test to diagnose either problem. Any other major illness, from cancer to multiple sclerosis to arthritis, can contribute to depression too – not just because being sick is depressing, but through poorly understood inflammatory pathways.

The most important other condition that resembles depression is bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is a combination of occasional depression with occasional hypomania/mania. Hypomania/mania is the “opposite” of depression – periods lasting a few days to a few weeks when you have much more energy than normal, feel better about yourself than normal, barely sleep but don’t feel tired, are more likely to start ambitious projects, and are more likely to make impulsive decisions about things like drugs / sex / wild parties. Some people’s hypomania is less fun and just feels like being amped up / on edge / really angry all the time. Some people become psychotic during mania and start hearing voices, believing they’re God, or acting in bizarre ways; other people will never experience anything like this.

Although bipolar people have depressive episodes, it’s important to distinguish that from normal depression. For one thing, different treatments work (including different medication). For another thing, a lot of depression treatments will push you into hypomania/mania, so it’s very important to avoid them or at least be extra careful.

If you’re not sure if you’re bipolar, talk to a psychiatrist about it before trying anything on this page.

2. How do you treat depression?

Lifestyle changes are very effective for depression, but they’re hard to do – part of being depressed is not having enough energy to make big changes to your routine and stick with them. So sometimes it’s helpful to start with something else and add in lifestyle changes as you start to feel up for them.

Psychotherapy and medication are both about equally effective at treating depression on average , but one or the other might work better for specific people. Both together work better than either one alone. Some people will find medication has intolerable side effects, and others will find psychotherapy is boring, unproductive, or hard to get to, so nobody should feel obligated to try any modality that doesn’t feel like a good fit for them.

If lifestyle changes, medication, and psychotherapy don’t work, there are some more-involved but very powerful strategies for dealing with treatment-resistant depression, including wake therapy, ketamine, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and electroconvulsive therapy.

To skip to more specific advice on regimens for treating depression, go to section 2.6.

2.1. What kind of lifestyle changes help with depression?

By far the most powerful treatment for depression is GETTING AWAY FROM THE DEPRESSING THING. After that: diet, exercise, sunlight, and hygiene/routine/behavioral activation.

2.1.1: What do you mean by getting away from the depressing thing?

Some people know exactly why they’re depressed. The most common are depressing jobs, depressing relationships, and (surprisingly often) depressing grad school programs. Their first priority should be to escape the situation. I realize this is easier said than done, and that if they’re still in the situation it’s probably because they have to be. Some people need to keep their depressing jobs to support themselves; other people want to stay in depressing relationships for the sake of the kids; other people stay in depressing grad school because they’re really close to getting a degree they want. I cannot second-guess your life choices.

But I will say this from having worked with many patients in similar situations – they are usually surprised by how much of their depression goes away after they get out of the situation. And more important, they usually overestimate how hard it would be to get out of the situation – remember, depressed people are pessimists, so the person who’s depressed because of their terrible job will naturally think they could never get another job, or that all jobs would be equally bad. Please, please, please don’t let your depressive bias keep you in your depressing situation.

One of my all-time favorite studies is Steven Levitt’s Heads Or Tails: The Impact Of A Coin Toss On Major Life Decisions And Subsequent Happiness. A researcher got subjects who were unsure whether or not they wanted to make a big change in their lives to decide by flipping a coin. The people who randomly ended up in the “do make the change” group ended up much happier six months later. (2 points on a 1-10 scale). This was especially true when the subject was considering breaking up (2.7 points happier) or quitting a job (5.2 points happier). This doesn’t mean everyone should break up with their partner and quit their job! But it does mean that if you really want to do that, and you’ve been holding off out of fear, you should consider not holding off.

2.1.2: What kind of diet helps with depression?

Most of the depression-fighting gains from diet don’t come from anything secret or fancy. They come from normal healthy eating. Less processed food, junk food, and soda; more whole foods, nutritious foods, vegetables, and water.

But if you want secret/fancy things, the best evidence is for the Modified Mediterranean Diet (“ModiMed Diet”) studied eg here. The study shows it having an effect size of 1.2, which if taken seriously would imply it’s three to four times as effective as the average antidepressant. I’m not completely convinced about that exact number – it’s hard to placebo-control a diet experiment (since people know if they’re eating better or not), and poorly-placebo-controlled antidepressant trials also appear three to four times more effective than the average antidepressant – but the evidence is certainly compatible with it having very impressive effects.

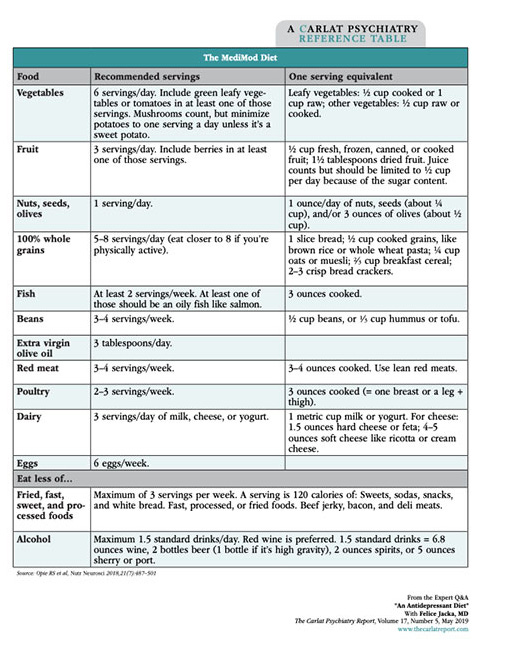

Here’s the diet the study used (source is here, but you won’t be able to read it without a Carlat Report subscription):

We still don’t know much about nutrition, and probably there are a lot of superfluous things in this diet, or a lot of potentially helpful things missing. We just don’t know what they are, and this diet is a decent guideline until we know more. The studies suggest it will start working at least within three months; it might work faster than that, but the researchers didn’t check.

See also the (free) Mediterranean Diet cookbook and the (non-free) book by Professor Felice Jacka on using modified Mediterranean diets in depression This is a slightly altered version of the Mediterranean diet, which is also recommended by cardiologists, endocrinologists, etc – see here for more about the general medical context.

2.1.2.1: What if I have special dietary needs (vegetarian/vegan/paleo/gluten-free/etc)?

You can probably find versions of the Mediterranean diet suitable for your situation:

– Mediterranean diet for vegetarians

– Mediterranean diet for vegans

– Mediterranean diet for paleo (see also here)

– Mediterranean diet for gluten-free eaters

In general, if you’re already following a healthy diet (eg a careful, health-conscious version of paleo), I’m not sure you have to worry too much about doing the Mediterranean diet in particular. It’s just one of many places you can start if you’re wondering how to eat healthy.

But also:

Vegans/vegetarians need to make sure they’re eating enough complete protein. Insufficient protein can cause various health problems, including mental health. You can find a list of good vegan protein sources here. You should also supplement with at least B12, iron, and creatine unless you’re taking a lot of care to make sure you get enough of these in your diet.

52% of vegans are B12 deficient (compared to 7% of vegetarians and almost no omnivores). B12 deficiency can cause fatigue and cognitive problems which can look like depression or make existing depression worse. There is some weak correlational evidence linking low B12 with depression. This is a reasonable B12 supplement to buy.

In a study in India, , 40% of vegetarian women vs. 7% of omnivorous women had moderate anemia, a common consequence of iron deficiency (anemia is much more common in women, but some men can get it too). Symptoms of anemia include looking pale, feeling easily exhausted, feeling an urge to eat weird things like ice or dirt, and – yes – depression. This is a reasonable iron supplement to buy.

Creatine is a chemical related to protein which is involved in muscles and energy production. There are no clear statistics on creatine deficiency, but vegans and vegetarians have about 25% to 50% less creatine than omnivores. Supplementation in vegetarians may increase memory and other aspects of cognitive function. There is weak preliminary evidence that creatine deficiency might be a risk factor for depression.

If you don’t eat fish, you might not get enough omega-3s. Omega-3s seem vaguely linked to all kinds of mental health issues, although it’s been hard to establish with certainty that supplementing these is helpful. Non-fish-eaters might still want to consider eating non-fish sources of omega-3s, like flax seeds or walnuts, or taking supplements. Most studies that found supplementation helped got effects only from very high doses (around 2 g daily), more than you could realistically get from capsules – so if you are supplementing for this purpose you should consider liquid oil. You will need to store these in the refridgerator to keep them from spoiling. This is a reasonable brand, or if you are vegetarian you can get an algae-derived version

2.1.3: What kind of exercise helps with depression?

Again, the most important answer is “whatever kind you will actually do”. Almost all benefits come from exercising at all; getting the kind of exercise exactly right is less important. Some people even suspect that most of the benefits of exercise come from doing something, feeling a sense of accomplishment, and getting out of the house, as opposed to any particular biological effect of the exertion itself.

The research beyond that is low-quality and contradictory. Cochrane Review finds a faint signal that maybe resistance exercise helps more than aerobic exercise, but Doyne et al finds they work about the same, and Pennix et al say that aerobic exercise works better, at least in the elderly. Nobody is really able to confidently demonstrate even simple principles like “more exercise works better than less exercise”, or even that exercise is better than stretching. This is one reason I continue to wonder if the sense of accomplishment and getting outside is as important / more important than the exercise itself.

Do some kind of exercise that lets you have a routine and makes you feel accomplished when you finish it. Beyond that, who knows?

2.1.4: What’s the role of sunlight in treating depression?

It’s complicated.

Sunlight is required to set circadian rhythm. If there are too few or too many hours of sunlight for days at a time, your circadian rhythm becomes confused, and you risk becoming depressed. This is typical seasonal affective disorder, aka “winter depression”.

But also, sunlight seems immediately helpful for a lot of people. You might feel happier after a day at the beach than a day in a dark room. This might be related to serotonin – some studies have shown people have higher serotonin levels on sunny days. Beyond that, there’s a long list of chemicals – most famously Vitamin D, but also nitric oxide and others – that you need sunlight in general, or ultraviolet light in particular, to produce.

If you have seasonal affective disorder, you might find bright light therapy helpful. We understand bright light therapy and seasonal depression pretty well, and can make confident recommendations about how much you need and how to get it. But even if you don’t have a seasonal depression (or in addition to bright light therapy even if you do) consider going outside more and getting more sunlight.

2.1.5: What’s the role of hygiene, routine, and behavioral activation in treating depression?

Depression manifests as aberrant learning. For some reason, your brain has “learned” that you’re bad, useless, worthless, incompetent, et cetera – ie it has a prior on all of these things. Treating depression partly involves fixing the aberrant learning by tuning various chemical parameters. But it will go faster if you actively “unlearn” this by doing things which make you feel better about yourself.

One important way to do this is hygiene. It only takes a few minutes to brush your teeth, shower, shave, etc, but it’s a powerful signal that you’re able to accomplish some minimum level of daily living. I don’t want to trivialize how hard it is for some depressed people to accomplish this – but that’s exactly why doing it anyway is a powerful signal that you’re working on escaping depression.

The same is true of otherwise keeping a daily routine. Don’t push yourself or try to make yourself do things you know you’ll fail at. But things as simple as “eating three meals a day, at normal meal times” or “going to bed at the time you want” or “taking a walk every morning” are powerful cues for normality that will help fight depressive cognitions. Expose yourself to situations where you will win small successes, and try to avoid ones that will go badly and make you feel worse. If you can’t do this, redefine “success” until you can.

I once read an account by someone who said their mood was correlated with how many rooms they had been in that day. If they spent the whole day in their bedroom, by the end of the day they’d feel terrible. If they made it to their kitchen, they’d feel a little better. The local cafe, better still. They seemed to feel some direct treatment effect from “novelty”, even the novelty of a different room in their house. I have never forgotten this and it strikes me as borne out by my own experience and that of my patients.

This is one of the reasons I think exercise works for depression – it’s a way of getting a small, controlled success that will make you feel like you’re accomplishing something. Also it sometimes brings you outside, or at least creates some kind of novelty in the sense of feeling weird because you’re sore or exhausted or something.

There’s an interesting finding that depressed people tend to listen to sad music. I am tempted to tie this into a general tendency for depressed people to stay in bed, keep the windows shut, avoid other people, and think about the worst things they’ve ever done – all of these suggest that the depression is somehow in control, trying to maintain itself. It’s surprisingly productive to take your depressed instincts as a guide for what not to do. Listen to happy music, go to interesting places, keep the windows open with sunlight streaming in, see your friends, think about happy things. All of this will “feel wrong” and your instincts will be pushing against it. You should try your hardest to do it anyway

This is called “behavioral activation”, and extensive studies have shown it to be as effective as medication and more effective than some complicated therapies. If you want to learn more, there’s a guide available here.

One caveat: please don’t let your depression use behavioral activation as another weapon against you! A common thought pattern is “I should use behavioral activation” -> “I’ll go do ALL THE THINGS!” -> “Oh no, I didn’t manage to do all (or any) of the things I wanted to do” -> “My depression is my own fault because I’m too worthless to do this easy cure, and I’m a bad person”. This is one reason I try to stress that all of these techniques are willpower dependent, and should be pursued only proportional to how much willpower you have. Think of it as investing – you start with a little willpower, you invest it in strategies that help treat depression, you get a little more willpower back, you invest that in more strategies, and so on. If you try to spend more than you have, it won’t work; that’s not your fault, it just means your depression is very bad. If you have zero willpower, not enough enough to be the seed for a tiny investment, then you should start with medication and only pursue willpower-requiring strategies if the medication give you that first little seed of willpower.

2.2. What kind of therapies help with depression?

As usual, it’s hard to study therapies, and the two most common results are “all therapies seem pretty okay” and “whatever kind of therapy the person running the study likes is great”. This happens often enough to make people skeptical of ranking therapies, and the usual advice for depression is to go with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), probably the best-studied and most common therapy style. Nobody can say with confidence that CBT is “the best”, but it’s a reputable and accessible form of therapy, and there’s no evidence that any other form works better.

Almost every therapist is somewhat influenced by CBT and will offer “CBT-style”; fewer therapists offer pure by-the-book CBT (sometimes called “manualized CBT”). There is not much evidence that manualized CBT is any better than CBT-style therapies, although as usual some individuals might find one form better than the other.

The cognitive part of CBT involves monitoring and challenging your thoughts. Depressed people have specific patterns of distorted thinking – a minor setback can become “I never do anything right”, or a bad day can be “everything always goes wrong for me, so it’s hopeless”. Cognitive therapy involves ruthlessly watching for and challenging those thoughts. It’s not about wearing rose-colored glasses and being a moron – if your thought is “I’m bad at social skills” and you are bad at social skills, you don’t need to pretend you’re super-popular. It’s about recognizing filters that are distorting your thoughts – preventing “I’m bad at social skills” from becoming “nobody likes me and I’m inherently unloveable and they’re right not to love me and I should die”. This sounds easy but is actually hard.

The behavioral part is mostly behavioral activation, as mentioned above. Figure out things that make you happy, then do them. Exercise routines, visiting friends, eating healthy, or even just watching a TV show you like. Respond to a bad mood by doing things that make your mood better, not worse. This also sounds easy while being hard.

Every part of cognitive behavioral therapy sounds and feels obvious. Partly this is because CBT is the ancestor of most of today’s psycho-babble and self-help, so its advice has become cliched. But another part of it is that knowing things isn’t enough. I know that if I lifted weights every day I could become very strong, I even know some more complicated body-building advice, but the advice itself is nothing; the practice is everything. Cognitive behavioral therapy blurs the line between knowledge and practice; it involves practicing knowing things and thinking things. The number one misstep people make is believing that since they already know the thing, they don’t need to practice. This is wrong, and a good CBT therapy or course will be as much about building a routine to practice the skills as it is teaching you what you need to know.

Other forms of therapy for depression are harder to find and of more variable quality, but if you really want them, you should go for it. Studies show that how excited a patient is about a therapy, and how much they believe in it, is an important factor in how well it works. If there’s some other therapy you’re more excited about than CBT, go for it. But if it fails, CBT is a nice dependable workhorse.

2.2.1. How can I get a therapist?

It’s always easier to find someone through your local network than to do it blindly. If you have a primary care doctor or a psychiatrist, ask them if they have therapists they like. Otherwise, if you feel comfortable, ask your friends.

If that comes up dry, and you’re in the US, the most straightforward way is to go on https://www.psychologytoday.com and use their therapist search tool to look for providers in your area. You can filter for what kind of conditions the therapists specialize in (everyone will say they specialize in depression), what kind of therapy they do (if you don’t have any other preference, try CBT), and whether or not they accept your insurance. Many therapists, including many of the best, don’t accept any insurance and will be expensive ($100 – $200+ per session, expect to need at least 10+ sessions). Also, many therapists on there will be full and not accepting new patients, and there will be no sign of this until you call them and ask for an appointment. You may have to go through a lot of them before you find someone you like who has availabilities.

2.2.2. How can I get therapy without a therapist?

Good news; several studies have found that therapy from a book, or off an app, or via some other kind of course, is just as effective as therapy from a professional therapist. It’s also cheaper and, for a lot of people, easier. I’m going to mention some of my favorite products below, but I haven’t tried out that many and I encourage you to explore further and let me know if you find anything good.

David Burns is one of the gurus of cognitive behavioral therapy. His book Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy is the canonical guide for do-it-yourself-CBT. I understand he has just put out an updated book, Feeling Great – I have not read this one and can’t confirm it is as good, but the title seems promising.

Intellicare is a series of CBT apps; you can download it for free as “Intellicare Hub” here or on the Google or Apple stores. I have never tried it, but the Carlat Report says nice things about it, and it has several successful studies under its belt.

2.3. What kind of medications help with depression?

Different medications will work for different people, and you should consult with your doctor. But here’s the algorithm I tend to use:

Most patients will want either escitalopram or bupropion as first-line treatment. These medications are easy to use and have fewer side effects than most others.

Advantages of escitalopram: it’s slightly better at dealing with anxiety, rumination, and obsessive thoughts, although some studies have challenged this. Disadvantages of escitalopram: it frequently decreases sex drive/ability/performance, and occasionally causes tiredness, weight gain, or emotional flatness. Read more at my page on SSRIs.

Advantages of bupropion: it gives you more energy and makes it easier to do things. It sometimes makes you lose weight. Disadvantages of bupropion: it sometimes makes anxiety worse, although some studies have challenged this. It can sometimes stimulate you too much and make it hard to sleep.

If one of these doesn’t work, try the other. If neither of them work, and you’re feeling optimistic, you might want to try a different SSRI, maybe sertraline. If that doesn’t work, move on to second-line treatments. Some of the better second-line treatments are duloxetine, mirtazapine, and amitriptyline.

Duloxetine is an SNRI, which supposedly means it might have some advantages over SSRIs, although studies are not completely clear. It might be better for patients with chronic pain, since it sometimes helps this also. I tend to avoid the other popular SNRI, venlafaxine, because it has very difficult withdrawal and no obvious advantages over duloxetine.

Mirtazapine is a mediocre antidepressant which is very good at making people hungry and sleepy. If you don’t want to be hungry and sleepy, this is definitely not the antidepressant for you. If you do want to be hungry and sleepy, maybe because your symptoms include insomnia and loss of appetite, mirtazapine is great. Most people are able to take it at night, get a normal night of sleep, and not be excessively sleepy when they wake up in the morning, but if that’s not you then you might have to switch to something else.

Amitriptyline is my preferred tricyclic, a large and sprawling class of older antidepressants. Other people might have different preferred tricyclics; imipramine, nortriptyline, and clomipramine are all reasonable choices in different situations. It can also cause tiredness and weight gain, and has a small risk of heart problems in vulnerable/older people. On the other hand, in Andrea Cipriani’s massive meta-analysis of antidepressant efficacy, it ranked first out of 21 different drugs (my third- tier suggestions weren’t studied, because the researchers were cowards).

If these don’t work, some people tend to give up. I would recommend they instead move on to potential third-line treatments:

Tranylcypromine is a MAO inhibitor, an unusual older class of antidepressant. These are very effective and tend to work even in otherwise treatment-resistant patients. But they have potentially serious interactions with many foods and medications, and you have to be very careful to avoid these while taking them (for example, you can’t eat many types of cheese). Many psychiatrists refuse to prescribe this medication because they are cowards, and I don’t have a good solution to this.

Ketamine is – well, we are still trying to figure out exactly what ketamine is, but it seems to work. I will have a separate page up soon about ketamine-related options, but I would put it at this point in the treatment algorithm (and not before) because it’s hard to get, and even when it works it’s hard to sustain the effect. Maybe this should be a second-line option and I’m being a coward by putting it so low down.

Antipsychotics are a class of drugs usually used against schizophrenia, but they also seem to have some role in depression. I hate using these because they have various concerning side effects if used for too long, but I will grudgingly include them at this part of the treatment algorithm. The usual procedure is to take an SSRI and use an antipsychotic, probably aripiprazole or quetiapine, on the side. Aripiprazole might make you restless, and quetiapine will make you sleep more and gain weight. Either one when used for too long increases your risk of metabolic problems (eg diabetes) and various terrible movement disorders (eg you can’t stop smacking your lips, and this problem never goes away). I don’t like these, but they sometimes work, and I can’t leave them out of the algorithm completely.

Pramipexole is a medication used for restless legs syndrome which, according to one study, is remarkably effective against treatment-resistant depression at a very high dose. I have never been able to get my patients to a high enough dose to test this; they get too many side effects and give up. If you have used pramipexole for depression, please email me with your story.

Psilocybin is magic mushrooms. They’re illegal, but studies suggest they probably treat depression very well. I don’t know enough about this yet to give specific advice, but will try to have more here eventually.

If none of these work, do ECT.

I haven’t really been convinced there’s much role for thyroid hormone or lithium as a main strategy for unipolar depression unless you have some special reason to want to use these (for example, lithium to make someone less suicidal, or thyroid hormone to correct hypothyroidism). Venlafaxine has high withdrawal potential and few obvious advantages over duloxetine. Desvenlafaxine, vilazodone, and vortioxetine are expensive without having obvious advantages over much cheaper drugs, and I can rarely find a use for them. The seligiline patch is more expensive than, and probably worse than, other MAOIs, so I rarely use it.

2.4. What kind of supplements help with depression?

As always, supplements are poorly studied and any attempt to discuss or rank them will be one part looking over terribly-conducted studies with a fine-toothed comb, plus one part intuition and anecdotal evidence. I am listing some very preliminary thoughts on depression supplements below, and will try to have longer pages about each of these up eventually, listing what the evidence is and why I come to various conclusions. Until then, please accept my apologies for this being very inadequate.

The most-studied and best-supported supplements for depression is l-methylfolate. Tryptophan/5-HTP, SAM-e, fish oil and St. John’s Wort may also be helpful. Less-well-studed but promising supplements including Zembrin and polygala tenuifolia. I am currently avoiding discussion of tianeptine, a foreign antidepressant which is sometimes sold as a supplement in the US, until I figure out the legal gray areas around it, but you might consider looking into it on your own. Going through the others one by one:

L-methylfolate is a form of folic acid, aka Vitamin B9, common in various vegetables. It’s part of various important chemical processes in the body, including the synthesis of serotonin, and various studies support its use in depression. Some people will try to claim that a gene called MTHFR is very relevant here, but I disagree with this and will have a page up about it eventually – the summary is that you should consider using l-methylfolate regardless of what allele of MTHFR you have. I’ve listed this supplement first because it’s the only one which has been officially approved by the FDA as safe and effective for depression. The FDA-approved version is called Deplin, and is prescription-only and more expensive, but it’s chemically identical to regular l-methylfolate which you can buy without a prescription in stores. Be careful as many stores will sell 1 mg tablets, but the recommended dose is 7.5 – 15 mg daily. You can get l-methylfolate 15 mg here.

Tryptophan is a chemical found in food (especially eggs, seeds, and milk). In the body, it gets turned into 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) and then 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), aka serotonin. Serotonin is an important mood regulatory chemical which we often try to increase during depression treatment, but if you consume serotonin directly, your body won’t be able to absorb it. The closest you can do is consume tryptophan or 5-HTP, and trust your body to absorb it and convert it into serotonin. Both of these chemicals are used for depression, and the few studies that have been done are mostly positive, for example this 2002 meta-analysis by Cochrane Collaboration. A more recent study finds 5-HTP works approximately as well as traditional antidepressants. Everyone agrees these studies are weak and low-quality and we can’t be sure of anything yet, but welcome to the world of depression supplementation. Early concerns about this potentially causing severe eosinophilic reactions don’t seem to have panned out, and might have been based on defective manufacturing processes which have since been fixed. A reasonable dose of 5-HTP would be to start at 100 mg daily, then go up to 200 and finally 300 mg daily after a few weeks. Don’t take this with any other serotonin-related medications without clearing it by your doctor first. You can find a reasonable brand of 5-HTP here.

SAMe is short for s-adenosyl-methionine-e, a chemical involved in folate and serotonin metabolism. It comes from a chemical called methionine found in various foods (especially eggs, seeds, and meat), which your body converts into SAMe. Almost every part of folate and serotonin metabolism has been investigated for its role in depression, and SAMe has come out better than most. This meta-analysis has the best summary: SAMe significantly beat placebo in three out of five placebo-controlled studies; in four head-to-head trials against antidepressants, it did about equally well. As always, these studies are weak and susceptible to bias. I am positively predisposed to this substance because my girlfriend has used it successfully against depression for many years, and reports consistently becoming more depressed when she forgets to take it. A low dose is 400-600 mg daily; a high dose is 1200-1600 mg daily; as always, start low and go up slowly, over the course of weeks. This is a reasonable brand.

Fish oil is various omega-3 fats, especially EPA and DHA, found in oily fish like salmon. Some people noticed that cultures that ate lots of fish had less depression, and ever since scientists have been trying to prove that fish oil treats depression, with wildly varying results. Liao et al analyze 26 studies totalling 2160 people and find it does, with effect size of 0.5, better than most antidepressants. Deane et al study analyze 31 studies totalling 41470 people and find it doesn’t. I can’t overemphasize how much great work by brilliant scientists has gone into this question, nor how totally useless and conflicting all the results have been. Oily fish are a generally healthy food, so you might as well eat them just in case. In terms of taking fish oil supplements, the jury is out. If you do choose to take them, the type and brand and dose become more important, since some of the debate centers around whether fish oil dosing might just be very hard to get right. Versions with higher EPA than DHA seem to fare better in research, and higher doses might be better than lower. Also, you should strongly consider refrigerating your fish oil so that it doesn’t get rancid, which aside from being gross will make it work less well. This brand is probably a reasonable choice, with one pill/day being a low dose and two/day being higher. If you are vegan, you can get this from algae rather than fish, but it’s harder to find the right EPA/DHA ratio (high) – this brand is the best I can do.

St. John’s Wort is a plant which has been used in herbal medicine for centuries (its name may come from the Knights of St. John, who used it to treat wounds while crusading). The most important active chemical, hyperforin, might be a weak reuptake inhibitor of various chemicals, including serotonin (which would technically make it an SSRI), but as far as I can tell this is too weak to really explain its effects. A meta-analysis of 35 studies including 6993 patients suggests it works, but other studies show no benefit. German studies tend to do the best and American studies the worst, which might either reveal something about those countries’ cultural biases, or about the different strains and extracts of the plant used in the two countries. This herb is infamous for interacting with various medications, and if you’re taking anything else you should talk to your doctor before starting it. This seems like a reasonable brand, but I’m open to suggestions for better ones.

Zembrin is an extract of kanna, a South African plant. It appears to be an SSRI, but also to have other less-well-understood antidepressant properties that make it work a little faster. It has not been rigorously tested in studies, but has been helpful to me and several people I know. You can read more about it at its Lorien page.

Polygala tenuifolia is a Chinese herb. It is under investigation as a rapid-onset depression treatment that may act on NMDA and AMPA receptors, perhaps similarly to the rapid-onset depression treatment of ketamine. It is still extremely experimental and has few studies in support, but early anecdotal evidence is optimistic. The only really credible source for it right now is here, and the recommended dose is 100 mg three times a day. Even more than other substances on here, this one should be considered experimental and not left as the mainstay of important depression treatment.

2.5. What else treats depression?

There are two powerful depression therapies that are more physics than chemistry: trans-cranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

In TMS, a machine delivers magnetic stimulation to your brain. This seems to overall strengthen neural synapses; since depression seems to be related to pathologically weak synapses, this should improve depression.

The procedure itself is surprisingly non-scary. You go to a clinic and sit in a chair with a magnet on top of it. The doctor turns the magnet on. It’s pretty loud, but otherwise unobtrusive; you probably won’t feel anything, or might only feel a little tingling. You can read or listen to music while it’s happening. A session usually lasts 30-40 minutes. When it’s done, you’ll feel perfectly normal and can drive home and do whatever else you would do during a normal day. You may need to have sessions 3-5 times a week for 4-6 weeks to get results. Side effects include headaches and not much else.

Meta-analyses suggest TMS is effective. There are not a lot of studies comparing it to medication, but it’s probably about as effective as medication, maybe a little bit more. Even though you will stop TMS after 4-6 weeks, most people who recover during TMS don’t become depressed again (see the page on dynamical systems for an explanation of why that might be).

I tend to recommend medication before TMS. It’s easier; going to a TMS clinic for 30 minute sessions 3-5x/week for 4-6 weeks is a big time commitment and doesn’t fit with a lot of people’s work schedules. Also, TMS is expensive, and insurance won’t always pay for it, especially if you haven’t tried medications first. Also, it’s really annoying if you make the time commitment and pay the money and then it still doesn’t work, which often happens. I usually try at least one third-line antidepressant treatment before referring someone to TMS.

In ECT, a machine delivers strong electrical current to your brain. This causes a seizure, which also seems to overall strengthen synapses somehow and improve depression.

ECT is similar to TMS in some ways. It also involves going to a clinic and being connected to a machine. It requires a similar time commitment – usually an hour per treatment, 3x/week, for 2-4 weeks. It also usually keeps working long after the treatments have stopped.

In other ways, it’s totally different. There’s no comparison between the weak magnetic stimulation of TMS and the very strong electrical current of ECT. You have to go to a hospital for ECT, and you have to be anaesthetized first; the shock and resulting seizure are painful and scary, and you wouldn’t want to experience them when conscious. While TMS has few side effects, ECT seriously disturbs cognition, and you will probably be “out of it” and not thinking very clearly for much of the 2-4 week course. The most serious disturbance is to memory, and you probably will remember little or nothing of those 2-4 weeks going forward; some patients report difficulty recalling earlier memories as well, although this is rare and controversial.

But ECT works extremely well. I’ve seen it completely cure the most difficult patients, people who nothing else has worked for. It doesn’t have a 100% success rate, but it’s as close as you’re going to get.

Many patients are scared of ECT. A lot of this is the fault of old movies like One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest which present it as a scary punishment. Modern ECT is nothing like that. For one thing, you’re unconscious and don’t feel it. For another, you’re on what’s called a “neuromuscular blocking agent” which means you’re not really going to convulse (ie won’t flail your arms and legs around). For another, doctors try to minimize the current and the length of time in order to minimize side effects; although most people have temporary memory problems, long-term side effects are rare and usually much less than the cognitive side effects of depression. ECT is definitely scary and definitely logistically difficult to arrange; I still cannot recommend it enough for patients who have not done well with other options.

ECT is usually done at hospitals. If you’ve exhausted other treatment options, your psychiatrist will be able to refer you to a local hospital that performs it. If for some reason they can’t do this, call the hospital and ask if they have an ECT program. They’ll probably refer you to some screening clinic where they’ll interview you, tell you the risks and benefits, and eventually get you on board.

Finally, you can also treat depression through light therapy. See this page for more information.

2.6. What should I try to treat my depression?

Given that you have a limited budget of time and energy, which of the things mentioned above should you try first? The answer will depend on details of your depression, your life situation, and exactly what your time and energy budget are. But I’ve found that it’s really important to give people maximally concrete suggestions. So here are some regimens that a completely standard person could follow; they might or might not be appropriate for your situation.

First, check that you don’t have bipolar disorder – if so, you will absolutely need to see a doctor and go from there. Second, make sure your depression isn’t caused by some other issue like insomnia, drug abuse, anxiety, etc. Third, do everything you can to lower your level of life stress, like seeing if you can quit stressful jobs or leave stressful relationships. After that, figure out which of these regimens best fits your situation:

Regimen 1A: Person with access to a doctor, low time/energy budget: Ask your doctor for bupropion XR 150 mg; if not completely improved after one month, increase to 300 mg. If that doesn’t work, ask your doctor what to do next.

Regimen 1B: Person with no access to a doctor, low time/energy budget: Take 5-HTP 100 mg, increase after one week to 200 mg, increase after three weeks to 300 mg. If that doesn’t work, stop 5-HTP, wait one week, start St. John’s Wort, 900 mg daily, for one month. If that doesn’t work, you may need to either get a doctor or increase the time/energy budget you’re willing to commit.

Regimen 2A: Person with access to a doctor, medium time/energy budget: Ask your doctor for escitalopram 5 mg, increasing to 10 mg after two weeks. Start taking l-methylfolate 15 mg daily. Set yourself a regular sleep/wake schedule and stick to it. Choose a time of day and go on a 20 minute walk every day. Cut all soda, candy, and fried food out of your diet. If no improvement after six weeks, ask your doctor what to do next.

Regimen 2B: Person without access to a doctor, medium time/energy budget: Supplements as in 1B above. Set yourself a regular sleep/wake schedule and stick to it. Choose a time of day and go on a 20 minute walk every day. Cut all soda, candy, and fried food out of your diet. If that doesn’t work, you may need to either get a doctor or increase the time/energy budget you’re willing to commit.

Regimen 3A: As 2A above, but add 2g EPA-dominant fish oil every day. Start light therapy, 10,000 lux from 8 – 8:30 AM every day. Replace 20 minute walk with 20 minute jog. In addition to cutting out junk food, switch to a strict modified Mediterranean diet. Read Feeling Great and do all exercises listed in it. If no improvement after six weeks, ask your doctor what to do next.

Regimen 3B: As 2B above, but add 2g EPA-dominant fish oil every day. Start light therapy, 10,000 lux from 8 – 8:30 AM every day. Replace 20 minute walk with 20 minute jog. In addition to cutting out junk food, switch to a strict modified Mediterranean diet. Read Feeling Great and do all exercises listed in it. If no improvement after six weeks, either get a doctor or look through the rest of this page for more suggestions.

This should be pretty straightforward, with the exception of the difference between 1A and 2A – why do I recommend bupropion in 1A and escitalopram in 2A? Mostly because 1A – the person with low time/energy budget – seems to be having more of an issue with energy, which bupropion can help. But also because in 2A, I recommend also taking the supplement l-methylfolate, which has theoretical reasons to think it might work better alongside escitalopram than bupropion.

Secretly I suspect Zembrin probably works better than 5-HTP or St. John’s Wort, but there’s not enough evidence for me to recommend it in good conscience.

2.7. If something helps treat my depression, how long do I have to do it for?

With medication, there’s a common rule-of-thumb for this. Keep taking it for six months after it starts working, then (if your doctor agrees) try stopping it (in whatever way your doctor tells you minimizes withdrawal effects). If it works, great. If your depression returns quickly in a way that seems correlated with stopping the medication, restart it, and try again after two years. If your depression returns quickly again in a way that seems correlated with stopping the medication, stay on the medication indefinitely or until something important changes (eg you quit a terrible job that was making you depressed).

Why six months? This is the average length of a depressive episode. Some people act like the episode “continues under the surface” even when a medication is treating it, and if you restart earlier than this, it will show up again. After six months, your depressive episode should be over, even “under the surface”, so you should get a fair trial of how you do without medication. As far as I know there’s no evidence for any of this, but the six month time period seems to work for a lot of people and is a nice bright line that reminds people to try coming off their medications at some point.

With lifestyle changes, you could potentially treat them the same way as medication, but also, consider sticking to a healthy lifestyle permanently.

About half of people who have one depressive episode in their lifetime will have more later, often in similar situations (eg if their first depression was after a bad breakup, they might get another after another bad breakup; if their first episode came out of nowhere, they might get another episode out of nowhere). Continuing lifestyle interventions that help treat your depression is an excellent way to prevent depression from recurring. Continuing medications is a less excellent way, both because taking medications when you don’t need them increases the risk of potential side effects, and because you can develop tolerance if you take medications too long – but some people find they need them and continue them for this reason, and if you really need them I think this is justified.