Play Money And Reputation Systems

For now, US-based prediction markets can’t use real money without clearing near-impossible regulatory hurdles. So smaller and more innovative projects will have to stick with some kind of play money or reputation-based system.

I used to be really skeptical here, but Metaculus and Manifold have softened my stance. So let’s look closer at how and whether these kinds of systems work.

Any play money or reputation system has to confront two big design decisions:

-

Should you reward absolute accuracy, relative accuracy, or some combination of both?

-

Should your scoring be zero-sum, positive-sum, or negative sum?

Relative Vs. Absolute Accuracy

As far as I know, nobody suggests rewarding only absolute accuracy; the debate is between relative accuracy vs. some combination of both. Why? If you rewarded only absolute accuracy, it would be trivially easy to make money predicting 99.999% on “will the sun rise tomorrow” style questions.

Manifold only rewards relative accuracy; you have to bet with some other specific person, and you only make money insofar as you’re better than them. All real-money prediction markets are also like this, and Manifold is straightforwardly imitating this straightforward design.

Metaculus has a weird system combining absolute and relative accuracy: all predictions are treated as a combination of “bets with the house” on absolute accuracy, plus bets against other predictors on relative accuracy. Why? As a kind of market-making function; even if nobody else has yet predicted, it’s still worth entering a market for the absolute accuracy points. This works, but has a lot of complicated consequences we’ll discuss more below.

(Manifold solves the same problem by having market makers be a specific user who wants the market to exist, and making that person ante up money at a specific starting price to make that happen. This seems a lot more straightforward and frees them from the complicated consequences.)

Zero Vs. Positive Sum

As far as I know, nobody suggests negative-sum markets; the debate is between zero vs. positive-sum. Technically markets with transaction costs can be negative-sum, but nobody is happy about this, just accepts it as a necessary evil.

Zero-sum is a straightforward choice that imitates real-money markets. Two forecasters bet, and whatever Forecaster A wins, Forecaster B must lose. This is nice because it produces numbers with clear meanings: if you have a positive number, you are on average better than other forecasters; the more positive, the more better.

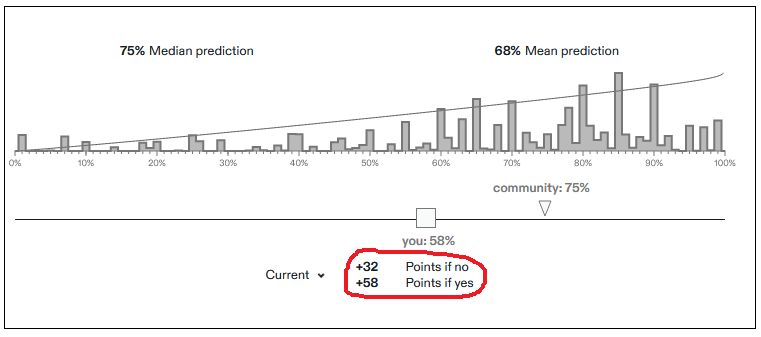

Positive-sum means that the house always loses; on average, you make money every time you bet. Metaculus is infamous for this; see eg this question on Ukraine:

If Russia invades Ukraine, this person will win +58 points; if it doesn’t, they will win +32 points. Why does Metaculus allow this? They want to incentivize people to forecast. If it’s zero-sum, you’re as likely to lose points by forecasting a question as gain them. In fact, if you’re not the smart money, you’re more likely to lose, much as normal people should try to avoid competing against Wall Street traders when picking stocks. Since Metaculus wants to harness the wisdom of crowds, and you need lots of people to make a crowd, they incentivize you with a better than 50-50 chance (sometimes a guaranteed chance) of getting points.

The disadvantage of this is that it makes points less meaningful; just because someone has a positive number of points, doesn’t mean they’re above average or have ever won a bet with anybody else.

Reputation Systems Aren’t About Reputation

I want to harp for a little longer on why this might be bad.

Suppose Susan is a brilliant superforecaster. She spends an hour researching every question in depth, at the end of which she is always right.

Suppose Randy guesses basically randomly. Or fine, maybe he’s slightly better than random, he has gut feelings, if the question is “will Russia invade Brazil?” he knows that won’t happen and says some very low number. But it’s not like he’s thinking super-hard. Maybe it takes Randy ten seconds to get a gut feeling and type in the relevant number.

In a zero-sum system, Susans (almost) always beats Randys. Susans end up with lots of points, Randys end up with few or negative points, the system works.

In a positive-sum system, in the hour it takes Susan to produce one brilliant forecast, Randy has clicked on 360 different questions. Who ends up with more points? It depends on whether your system rewards a brilliant answer 360x more than the baseline it rewards any answer at all. The above Ukraine question on Metaculus rewards a maximally correct answer 4x more than a lazy answer intended to most efficiently reap the free points - ~50 vs. ~200. So assuming an unlimited number of questions and both people investing the same amount of time, Randy would end up with about a 90x higher reputation than Susan.

Metaculus addresses this issue by . . . totally failing to address this issue and just accepting the consequences. It doesn’t seem so bad for them; their leaderboard contains many people who I know from other contexts to be genuinely excellent forecasters. But it turns a lot of people off from them.

More important, it lampshades an important quality of “reputational” systems: so far, none of them actually produce any kind of a reputation. By this I mean something like: if I claim “I have an IQ of 160” or “I can bench press 300 lbs”, people might be impressed by me. If I say “I’m a superforecaster in the Good Judgment Project”, the small number of people who know and care what that is will be impressed. I’ve heard people claim all of these things, but I have never heard anyone casually drop their Metaculus score in conversation, even in the weird heavily-selected circles where everyone knows about Metaculus and agrees it is good.

(I’m a relatively well-known blogger who writes a lot of things that may or may not be true, and I’m known to use Metaculus, and nobody has ever asked me my Metaculus score before deciding how much to trust me!)

I think this is partly because everyone understands that Metaculus scores are some combination of how good a forecaster I am, how much meta-gaming I do, and how much time I put into grinding Metaculus questions. But then, what’s the point? Your incentive for playing Metaculus is supposed to be getting a good reputation, but in fact this has no benefits, not even bragging rights!

I can’t deny that this system does, somehow, work. A lot of people use Metaculus (sometimes including me), and I would actually respect someone more if I knew they were on the leaderboard (probably through some assumption that Metaculans seem nice and honest, and even though the Randy strategy is easy, nobody cares enough to do it).

Still, part of me wishes that reputation systems could actually give someone a good reputation - that the big Wall Street firms would consider guaranteeing interviews to people on the leaderboards, or something like that. But right now they’re just not good enough to survive having any real-world consequences.

Play Money Systems: Better Than They Sound?

So what about zero-sum, relative-accuracy play money systems? This is the strategy used by Manifold, plus some of the real-money prediction markets that offer play money to Americans (like Futuur). It’s straightforward and it simulates a real prediction market closely. What could go wrong?

First question: why would anybody want play money? The obvious answer is that it’s a reputation system in disguise - the amount of play money you accumulate is a proxy for how good a forecaster you are - and an accurate one, unlike Metaculus’ reputation. This is mostly true, but with some complications. Manifold lets you buy their play money for real money, which in theory would destroy any reputational value. But they solve this by actually reputationalizing play money profits , which works:

For example, I am now impressed by/concerned by/suspicious of Robert McIntyre. What are you doing?

For example, I am now impressed by/concerned by/suspicious of Robert McIntyre. What are you doing?

A second potential reason people might want play money: on Manifold, you can use it to open your own questions, asking the market for information on a topic presumably of interest to you.

(this would be very straightforward if you were subsidizing the market, and the site encourages you to think of it as a subsidy - but is it? You bet your starting ante at some specific level. And usually you as market maker have more insight into the question than anyone else. Half the time it’s on your own personal life; the other half of the time it’s on some broader question which is selected for being something you care about a lot. Far from being a subsidy - money which it is easy for other people to get - this feels like smart money - money that other people should be scared to bet against. So how does this open the market at all? I’m not sure and willing to entertain the possibility that it doesn’t, that the system only holds together because everyone is having fun and nobody cares about the incentives, and that an ante of $1 would work just as well.)

Any broader problem with this system?

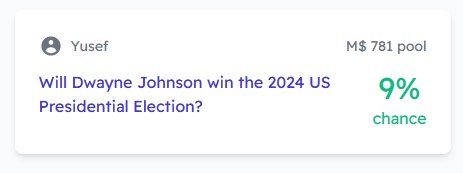

I mentioned this last week, but let’s look at it again. This is inexcusably wrong: there’s no way this guy (a wrestler with no political experience who hasn’t even announced he’s running) has a 9% chance of becoming President. Why is nobody correcting it? Because you’d have to tie up your limited supply of play money for 2.5 years to make a tiny profit: the site tells me that if I put in an average person’s entire starting allocation (M$1000), I’d only push the chance down to 2% (still not low enough!) and only make a $35 profit in 2.5 years (a ~1% rate of return) when time proved me right.

My conditional prediction market experiment seems to be failing for the same reason:

I posted about six books I was considering reviewing, and asked people to bet on which ones would get lots of “likes”. Only 44% of my book reviews get more than 125 likes, but every book I proposed is at >44% right now. Many are much higher - like this one, about a dry scholarly textbook explaining a famously incomprehensible form of psychoanalysis. I think all these markets are mispriced.

My guess is that people are using this as a way of voting for books they want me to review. They buy “yes” on books they like, but don’t buy “no” on books they don’t like, because that would be against the imaginary rules for the voting that they are falsely imagining this to be. Ideally, actual prediction market players would take these people’s money and drive the markets back down to the base rate. That’s not happening here, and my guess about why is: it’s a small return on a one-year-long market that might never actually trigger (if I don’t review the book, the conditions for the conditional prediction market aren’t met, and it resolves N/A). Nobody wants to lock up their limited play money for this.

Metaculus, for all their system’s problems, would get this one exactly right; since you’re incentivized to predict on every question with no limiting factors, lots of people would bet on this one; since the optimal strategy is to bet your true belief, everyone would bet something very low, and the probability would end up very low.

What to do? In the Manifold Discord, I recommended offering a per market interest-free loan of M$10, usable for a bet in that market only. Since it’s a loan, you don’t get free reputation by participating in as many markets as possible; if you’re not actually applying market-beating levels of work, you’ll only break even; if you’re worse than the market, you’ll lose money.

Still, if I could take out an interest-free M$10 loan on this market, I would. I’d bet NO, and in 2.5 years, I’d make a total of M$1 worth of easy money. If all two hundred-ish Manifold users did this, that would push the probability down to 1%, which is close enough to the real value.

Loans are complicated. For one thing, you’d have to prevent me from taking out the market-specific loan on this, selling my position immediately, and then reinvesting it into some flashier shorter-term question. For another, you’d either need a system of margin calls, or just accept that some people will go below M$0 sometimes (sure, let them go below $0, so what?) Still, I think this would solve a lot of mispricings. If it didn’t, the administrators could fiddle with the size of the loan until it did.

You could also experiment with a mechanism where market makers’ ante funds the loans, ie if you ante M$100 for a one year market, you’re promising to loan the first ten people who enter M$10 each to bet against each other with. I don’t know how to do that in a way which doesn’t reward people who show up early, which is undesirable since it makes the reputation system less valid.

I think the “play money has value because you can use it to subsidize play money prediction markets which have value because people want play money so they can subsidize play money prediction markets which…” loop is clever and could potentially work. So far Manifold has been running off of fun and early goodwill; I look forward to seeing how they solve these difficult problems as they try to scale past that level.